Introduction

Acute bacterial meningitis is a life-threatening infectious disease that, if not treated promptly and effectively, can lead to a poor neurological outcome or death [1]. Early clinical suspicion of bacterial meningitis and rapid administration of antibiotics is important to increase survival and reduce morbidity [1]. Streptococcus bovis (group D non-enterococcal streptococcus) bacteria is part of the bowel flora in 5% to 16% of adults [2-4]. Dissemination is responsible for a range of clinical presentations, including bacteremia, endocarditis, septic arthritis, and endophthalmitis [4]. S. bovis is a recognized but rare cause of meningitis in adults [4,5]. There is a strong link between S. bovis infection and bowel disease [2-7].

Case Report

A previously independent 62-year-old woman, was brought to the emergency room due to disorientation and agitation with inappropriate speech after sudden onset of severe headache and fever. There was no history of seizures, loss of consciousness, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, gastrointestinal and genitourinary symptoms. The patient lived on a farm and had a background of smoking, Buerger´s disease, chronic kidney disease, hip prosthesis and hyperuricemia, currently on allopurinol, pentoxifylline, iron, calcitriol and glucosamine.

On admission, the patient was conscious (Glasgow coma scale of 10), but confused, agitated and uncooperative. Physical examination revealed a regular pulse with tachycardia (102 beats/min), normal blood pressure (129/70mmHg) and normal oxygen saturation (96%) on room air. No stiffness of the neck or Brudzinski’s sign was evident. No focal neurologic signs were detectable. Auscultation of the chest revealed regular heart sounds, no murmurs and no other abnormalities.

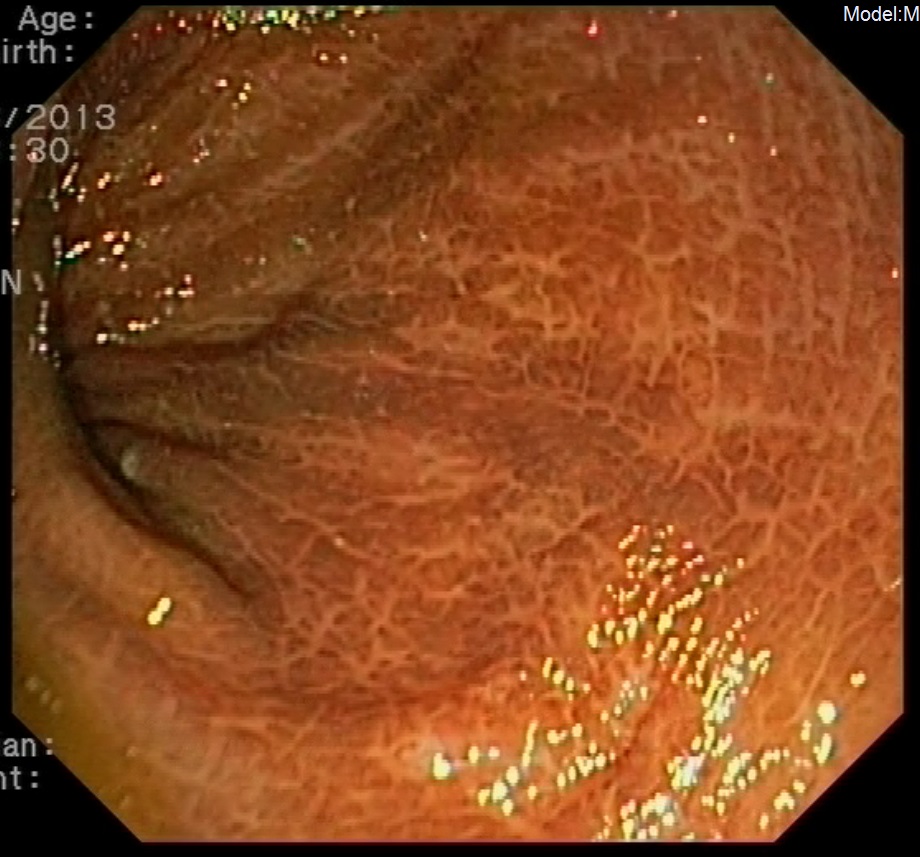

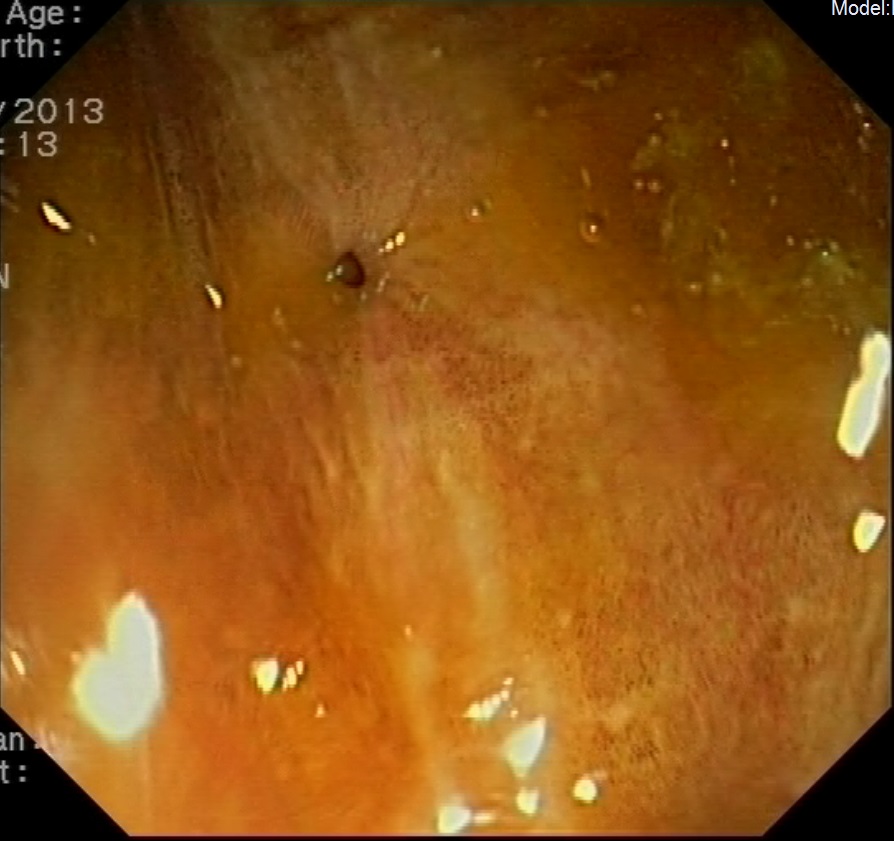

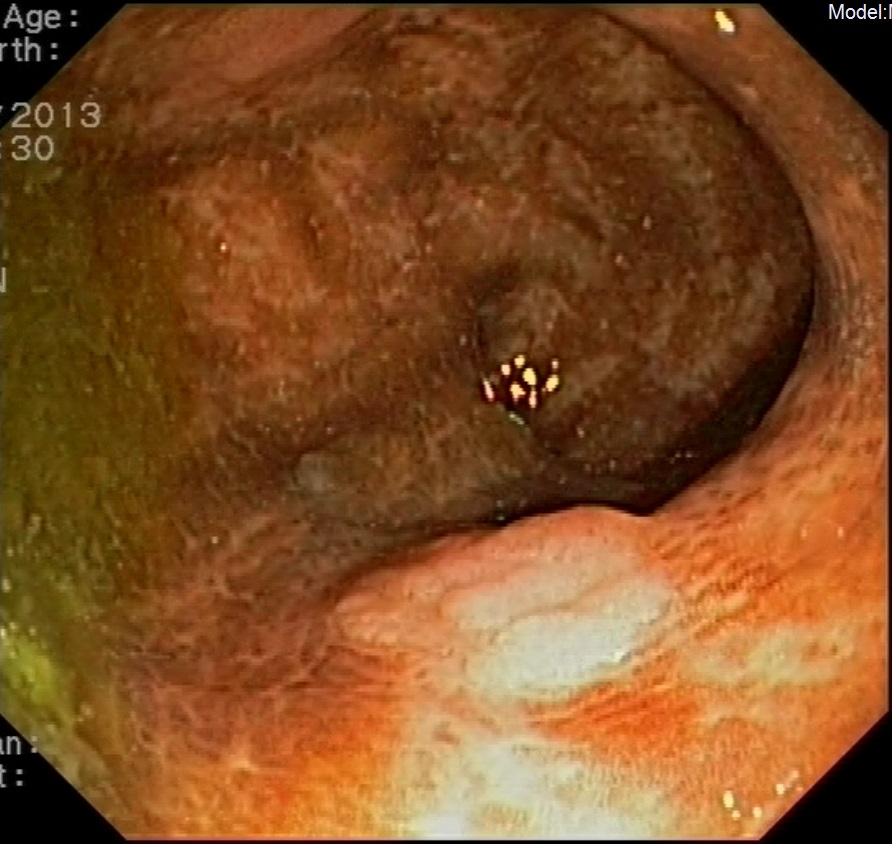

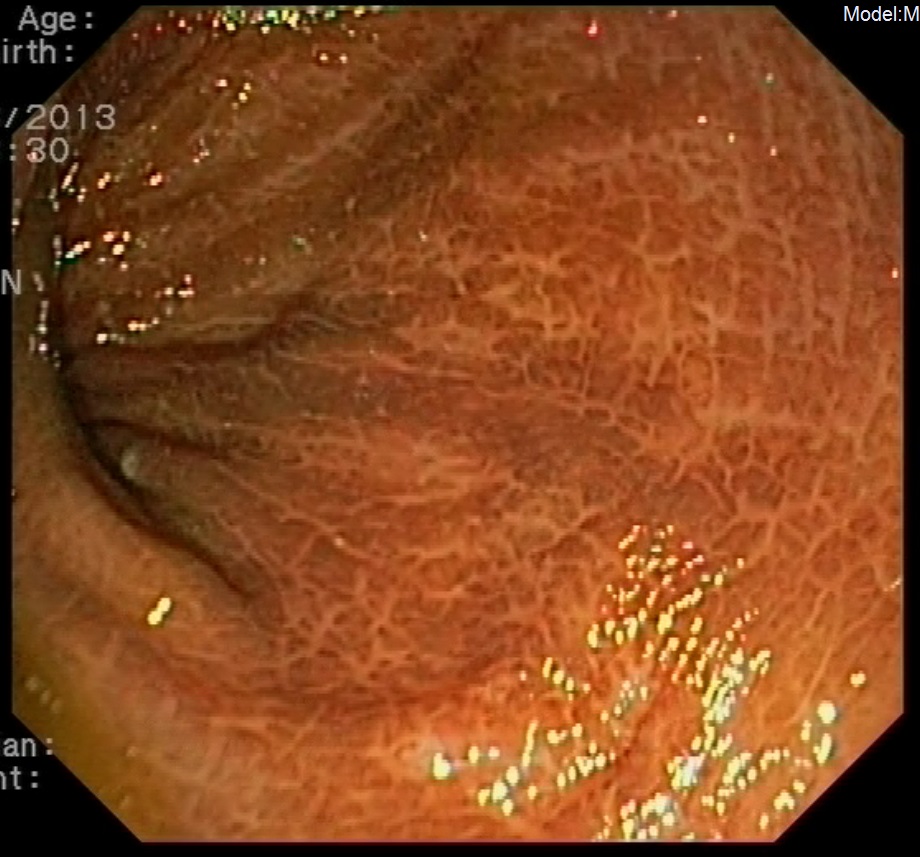

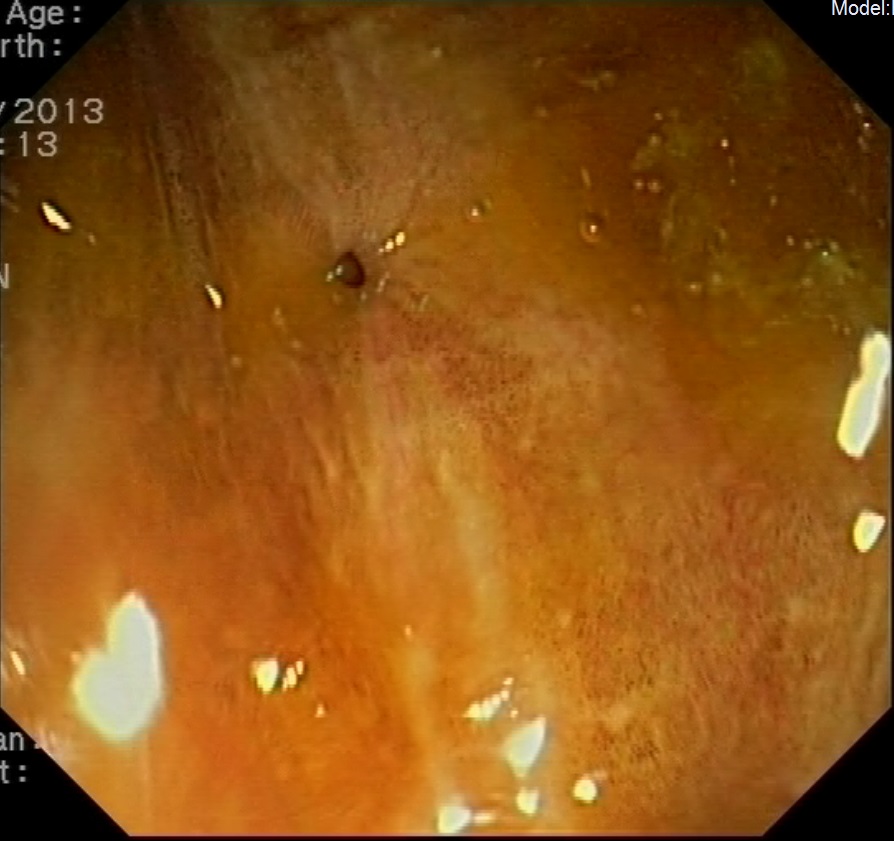

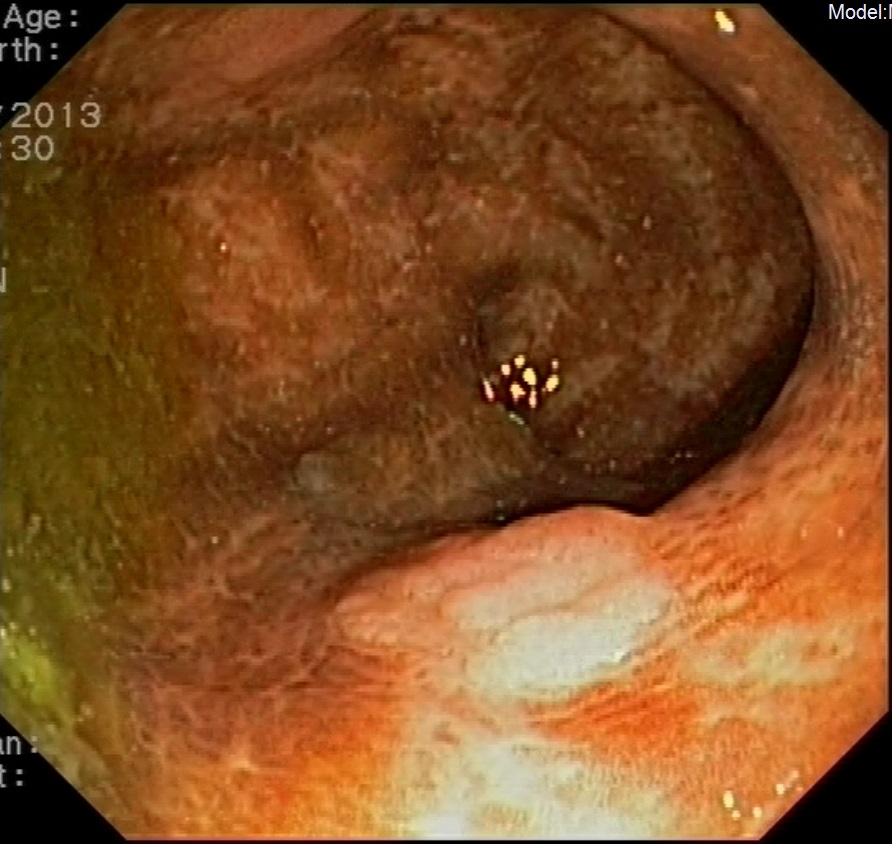

Laboratory tests showed leukocytosis with neutrophilia, macrocytosis and mild elevation of LDH and CRP. Computed tomography (CT) of the head was normal. A lumbar puncture was performed collecting a cloudy cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), revealling 1963 leukocytes/mm3 (predominantely polymorphonuclear); 10 red cells/mm3; undetectable levels of glucose and 132 mg/dL of protein. Direct examination and Gram staining of CSF were negative. A chest X-ray and an electrocardiogram were performed and they were normal. The patient was hospitalised for the clinical investigation to be carried out. After the blood and CSF culture results, a transthoracic echocardiogram was performed by an experienced operator, denying the existence of images suggestive of endocarditis. The colonoscopy revealed melanosis coli (Fig. 1), diverticulosis (Fig. 2) and an adenoma of the rectum (Fig. 3), which was excised. After the cultures of CSF and blood were collected, dexamethasone, ceftriaxone, ampicillin, and vancomycin were initiated empirically. On day five, the microbiological results were obtained. Both CSF and blood cultures revealed S. bovis, susceptible to penicillin G and third generation cephalosporin, as a single etiological agent of this infection. At this time, there was a significant clinical improvement. So, we decided to maintain the third generation cephalosporin and stop the other antibiotics. After a 14-day course of antibiotics, the patient remained asymptomatic, afebrile and culture negative after the therapy was stopped. She was discharged with excellent clinical outcome. The histology of the adenoma proved to be a low-grade dysplasia.

Discussion

The isolation of S. bovis from the lower gastrointestinal tract and, less frequently, from the mouth of healthy individuals is a well-known fact [2,3,6]. It has been an important cause of both bacterial endocarditis and septicemia. There is a well-established association between S. bovis septicemia and both benign and malignant gastrointestinal lesions, although the mechanism by which this happens is uncertain [2-6]. Some studies have suggested that lesions in the colonic mucosa can promote a specific niche for S. bovis, sometimes breaking of the mucosal barrier allowing the organisms to enter the bloodstream [3,4]. However, S. bovis is a rare cause of bacterial meningitis in adults, seldom described in literature, usually occurring in patients with an underlying disease, mainly immunosuppressed [2,4,5,8]. The patient we present was immunocompetent. Lately, meningitis caused by streptococci other than S. pneumoniae has been responsible for an increasing number of hospital acquired meningitis cases [4,9,10].

In this case, the gastrointestinal tract is the probable source of the infection, since the colonoscopy revealed melanosis coli, diverticulosis and an adenoma found near the rectum. There was no recent history of diarrhea, abdominal pain or intestinal bleeding that would suggest a diverticulitis episode. Probably the infection was due to a transitory subclinical diverticulitis, with bacterial translocation, bacteraemia and secondarily a central nervous system infection. According to what has been described in most published cases, the CSF Gram stain was negative.

The blood cultures were positive, favoring the hypothesis of related bacteraemia. Some cases of S. bovis meningitis have been associated with concomitant endocarditis. In this case, an experienced operator performed a transthoracic echocardiogram. Technical conditions were considered optimal for evaluation and images suggestive of endocarditis were not found. For this reason, a transesophageal echocardiogram was considered to be unnecessary [4,5,11].

In the presence of bacteraemia, endocarditis,S. bovismeningitis, or any association between them, the presence of an underlying pathology of the colon, due to the frequent association between these processes, must be ruled out and treated [11].

Although the treatment with penicillin G is usually sufficient, in our case, it was decided to maintain antibiotic therapy with a third-generation cephalosporin [1]. After a 14-day course of ceftriaxone, the patient was discharged with excellent clinical outcome.

The case is important because early recognition of clinical features, suggestive of meningitis is fundamental for timely diagnosis and treatment impacting on survival. The case is interesting in that the source of infection of the CNS has been the gastrointestinal tract and it has an important impact on health since it seems that a large number of patients (25 to 80%) with S. bovis bacteraemia have colorectal tumors [7]. According to the literature, the S. bovis is most likely a propagating factor for premalignant tissues. So, the early detection of colorectal adenomas or carcinomas in the course of these infections might be of high value in screening high-risk groups for colorectal cancer [7].

Figura I

Melanosis coli

Figura II

Diverticulosis of the colon

Figura III

Adenoma of the rectum

BIBLIOGRAFIA

References:

[1] Diederik B., Brouwer M.C., Thwaites G.E., Tunkel A.R. Advances in treatment of bacterial meningites. Lancet. 2012; 380:1693–702.

[2] Alonso J.L.P., Méndez C.A., Rodríguez F.G. Streptococcus bovis: an emerging pathogen.Med Clin.2007; 129 (9):349-351.

[3] Alazmi W., Bustamante M., O’Loughlin C., Gonzalez F., Raskin J.B. The association of Streptococcus bovis bacteremia and gastrointestinal diseases: a retrospective analysis.Dig Dis Sci.2006; 51:732-736.

[4] Silva, C.N.G.N., Araújo, R.S.C., Araújo-filho, J.A. Streptococcus bovis meningitis associated with colonic diverticulosis and hearing impairment: a case report.Infez Med.2011; 4:262-265.

[5] Cohen L.F., Dunbar S.A., Sirbasku D.M., Clarridge III J.E. Streptococcus bovis infection of the central nervous system: report of two cases and review.Clin Infect Dis.1997; 2:819–823.

[6] Herrera P., Kwon Y.M., Ricke S.C. Ecology and pathogenicity of gastrointestinal Streptococcus bovis.Anaerobe. 2009; 15:44-54.

[7] Abdulamir A. S., Hafidh R.R., Bakar F.A. The association of Streptococcus bovis/gallolyticus with colorectal tumors: The nature and the underlying mechanisms of its etiological role. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2011; 30(1):11.

[8] Beek D.V., Gans J., Tunkel A.R., Wijdicks E.F.M. Community-acquired bacterial meningitis in adults. N Engl J Med.2006; 354:44-53.

[9] Attanasio V., Pagliano P., Fusco U., Zampino R., Faella F.S. Four cases of meningitis by streptococci other than pneumoniae in adults: clinical and microbiological features.Infez Med.2006; 4:231-234.

[10] Cabellos C, Viladrich PF, Corredoira J, Verdaguer R, Ariza J, Gudiol F. Streptococcal meningitis in adult patients: current epidemiology and clinical spectrum.Clin Infect Dis1999; 28:1104-1108.

[11] Fernández M.C., Amado L.E.M., Carretero M.J.M., García E.C., González J.R. Streptococcus bovis meningitis. An infrequent cause of bacterial meningitis in the adult. Rev Neurol.2002; 34 (9):840-842.