INTRODUCTION

Multiple biliary hamartomas (MBH), also Known as Von Meyemburg Complexes (VMCs)1, are a rare entity that consists of small cystic lesions (multiple or nodular) caused by a malformation of the ductal plate of intrahepatic bile ducts2(ductal involution in the last embryonic stage)3.The prevalence of these lesions is low, ranging from 0.69 to 2.8% on autopsy series4, with a further small incidence of 0.6%, as Lin et al. showed in their biopsy series5.

They are more common in men and usually equally distributed by both hepatic lobes, varying in size and degree of differentiation6. Typically they present as small lesions, between 0.1 and 1.5 cm in diameter, but there are descriptions of larger lesions, reaching 3 cm7.

The MBH can be predominantly solid, cystic or intermediate, depending on the prevalence of fibrous stroma in the lesions, and can be easily confused with metastases, microabscesses and even biliary cystadenocarcinoma8.

In most cases these injuries remain asymptomatic, causing no changes in liver enzymes2throughout life and do not require any intervention3, commonly being accidentally diagnosed2.

MBH may occur alone or in the context of Isolated Polycystic liver disease (PCLD) and autosomal dominant polycystica kidney disease (ADPKD)3.

CLINICAL CASE

A 53-years-old woman, with history of anxiety, chronic cough and an isolated episode of supraventricular arrhythmia, was referred to our hospital with analytical changes in the cholestasis liver enzymes. She denied abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, gastrointestinal disorders, anorexia, weight loss or other symptoms. No report of alcohol consumption or illicit drugs abuse. She denied the use of herbal products, antibiotics, analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID).

The patient had no relevant pathological observations on physical examination. Her body mass index was 24.2Kg/m2. Laboratory tests showed increased alkaline phosphatase (AP) - 111 U/L (reference value 33-98) and gamma glutamyltranspeptidase (GGT)106 U/L (reference value 5-36) with normal transaminases, bilirrubin, albumin, INR and prothrombin time.

We conducted a deeper investigation with hepatotropic viruses serology, autoimmune study, iron metabolism, lipidic profile, protein immunoelectrophoresis, ceruloplasmin and alpha-1-antitrypsin assay which proved normal. Ultrasound showed a normal size liver, with a heterogeneous structural pattern, outlining some cystic elements, the larger with about 2mm. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy requested to rule out portal hypertension was normal.

A colangio-MRI (magnetic resonance image) was requested to clarify the previously described images on ultrasound. The study identified the presence of numerous nodulariform configuration images (figures1,2 and 3), hyper-intense on T2-weighted sequences, consistent with nodular cystic millimeter elements, related to the presence of MBH.

We performed no specific treatment and fluctuation on AP and GGT values was observed, never higher than 124 U/L for AP and 122 U/L for GGT.

Our patient maintains an annual surveillance with clinical, analytical and imaging control.

DISCUSSION

The MBH usually cause no symptoms or liver enzyme abnormalities2. Nonetheless, some cases may present as recurrent cholangitis or infection with liver tests abnormalities2, or single GGT elevation as described in a case of cholangiocarcinoma arising in MBH7.

In our patient, other causes of cholestasis were studied and excluded and there was not found any other condition that would justify cholestasis.

We present a case with an uncommon etiology for intrahepatic cholestasis, where the performance of MRI had a critical contribute to diagnosis.

As seen in this case, MRI plays a very important role in the diagnosis of MBH given the typical radiological feature presentation1with a hypo-intense lesion on T1-weighted images and a strong hyper-intensity of biliary hamartomas in T2 images, previously described by some authors1,4,7,9. These characteristics are not always sufficient to make an accurate diagnosis, especially in predominantly solid or intermediate lesions, often requiring a biopsy to exclude malignacy8. Still, in most cases, the MRI features allow to diagnose accurately, as demonstrated Tohmé-Noun et al.4in his study where a correlation of imaging and histopathological features aspects was performed.

In our case, there was no benefit in performing biopsy, given the typical characteristics in MRI, the size of the lesions and the favorable analytical evolution. It remains an open door in the future to exclude fibrosis or if there is a change in the size and characteristics of the lesions.

Another cornerstone of MBH is malignant transformation. It is rare and only described in a few cases from the literature7, but their presence seems to be a predisposing factor for the emergence of cholangiocarcinoma7,10. The high risk of malignant transformation associated with MBH is attributed to biliary stasis and prolonged exposure of the parenchyma to potential carcinogens present in the bile6. Song et al. suggest that the size of MBH is also a major risk factor for malignant transformation and recommend monitoring the size increase of the larger lesions11.

Therefore it is important to keep a regular follow-up of these patients, although there are no formal recommendations or surveillance protocol.

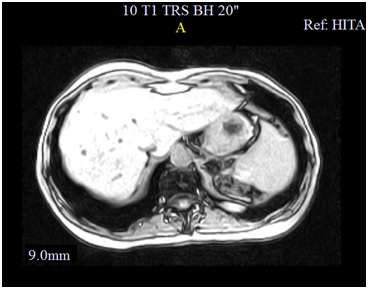

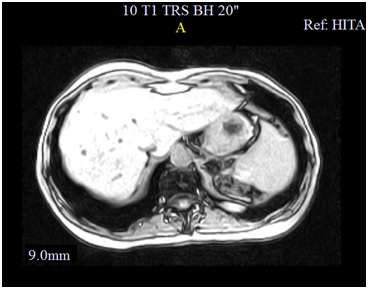

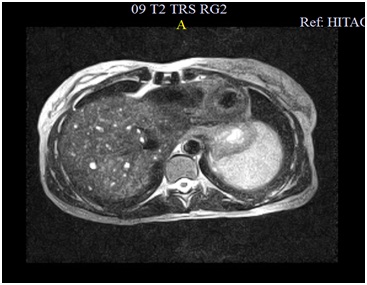

Figura I

Hypointense lesions on T1 weighted images of Cholangio-MR.

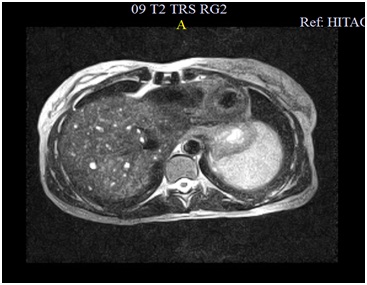

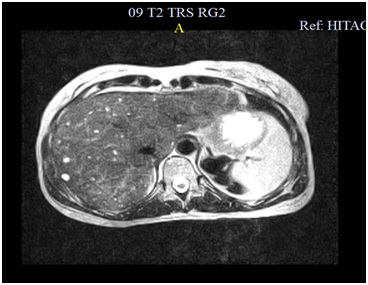

Figura II

Hyper-intensity of biliary hamartomas in T2 images of Cholangio-MR.

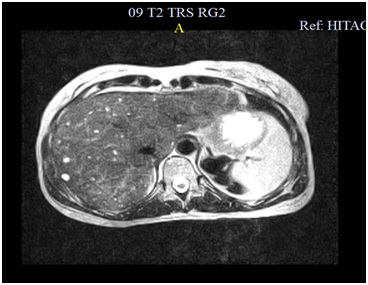

Figura III

Hyper-intensity of biliary hamartomas in T2 images of Cholangio-MR.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Gong J, Kang W, Xu J. MR imaging and MR Cholangiopancreatography of multiple biliary hamartomas. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2012;2:133-134.

2. Sinakos E, Papalavrentios L, Chourmouzi D, Dimopoulou D, Drevelegas A, Akriviadis E. The clinical presentation of Meyenburg complexes. Hippokratia. 2011; 2:170-173.

3. Cnosson WR, Drenth JPH. Polycystic liver disease: an overview of pathogenesis, clinical manifestations and management. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2014; 9:69.

4. Tohmé-Noun C, Cazals D, Noun R, Menassa L, Valla D, Vilgrain V. Multiple biliary hamartomas: magnetic resonance features with histopathologic correlation. Eur Radiol. 2008; 18: 493–499.

5. Lin S, Weng ZY, Xu J, Wang MF, Zhu YY and Jiang JJ. A study of multiple biliary hamartomas based on 1697 liver biopsies. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013; 25: 948-952.

6. Jain D, Sarode VR, Abdul-Karim FW, Homer R, Robert ME. Evidence for the Neoplastic Transformation of Von-Meyenburg Complexes. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2000; 24:1131-1139.

7. Kim HK, Jin So-Young. Cholangiocarcinoma arising in von Meyenburg complexes. The Korean Journal of Hepatology. 2011; 17:161-164.

8. Poggio PD, Buonocore. Cystic tumors of the liver: A pratical approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2008; 14(23): 3616-3620.

9. Liu S, Zhao B, Ma J, Li J, Li X. Lesions of biliary hamartoms can be diagnosed by ultrasonography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Int J ClinExp Med. 2014; 7:3370-3377.

10. Nakanuma Y,Tsutsui A,Ren XS,Harada K,Sato Y,Sasaki M. What are the precursor and early lesions of peripheral intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma? Int J Hepatol.2014:805973.

11. Song JS, Lee YJ, Kim KW, Huh J, Jang SJ, Yu E. Cholangiocarcinoma arising in von Meyenburg complexes: report of four cases. Pathol Int. 2008;58:503-512.