Introduction

Legionnaires’disease (LD) was initially described by Fraser, in 1977 as a lung disease which affected delegates attending the 1976 American Legion Convention in Philadelphia.1

Legionella is a Gram negative aerobic bacillus. The most common species is Legionella pneumophila, causing at least 80% of human infections.1,2 There are more than 70 serogroups known 2, from those, 1, 4 and 6 are the most frequently implicated in human infection.1,3 The habitat are natural waters, although they find the ideal conditions in manmade reservoirs where bacterial proliferation is enhanced (warm temperature and stagnation).4 Cooling towers, as source of aerosols, have been frequently implicated in community outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease.5 However, in 2014, a cluster of cases arose in Vila Franca de Xira (Portugal) and it was suspected that a person-to-person transmission can occur.6

Legionellosis includes Legionnaires disease (severe pneumonia), Pontiac fever (self-limited acute febrile illness) and extrapulmonary Legionella infection not associated with pneumonia.7

Neurological manifestations may develop in 40%-50% of patients.8 Cerebellar dysfunction (ataxia and dysarthria) is one of the rarest manifestations, affecting only 3,7% of patients.8

The authors report a rare presentation of Legionella infection, with exuberant and early neurologic involvement, suggesting that atypical symptoms of pneumonia should led to an active etiological investigation.

Case Report

A 62-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a five days history of high-grade fever, chills, anorexia, mild diarrhea, dry cough, and exuberant and progressive disequilibrium and dysarthria. He was already under amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, after been observed by his primary care doctor two days before.

He had a past medical history of hypertension and dyslipidemia. He was a non-smoker, worked as chief observer at the portuguese electricity company, had no contact with animals or other sick People and had been travelling in Portugal in the past two weeks, sleeping in different hotels without air conditioning.

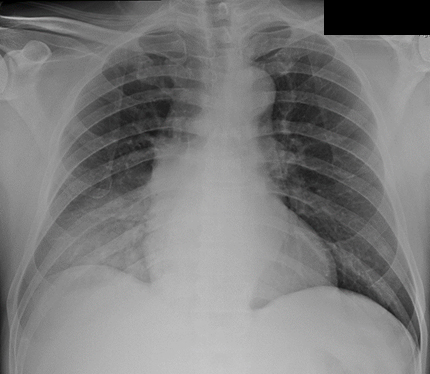

Upon admission he was tachypneic with an oxygen saturation of 92%, pulmonary auscultation revealed crackles in the lower third of the right hemithorax, gait ataxia, dysarthria and dysmetria were also identified. The remaining physical examination was unremarkable. Laboratory abnormalities were as shown in table 1. Chest x-ray showed a consolidation pattern in the right lower lobe consistent with pneumonia (figure 1). Head computed tomographic (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) did not show any abnormality.

He was admitted to the Intermediate Care Unit with the diagnosis of community acquired pneumonia (CAP) with multi-organ dysfunction, and was empirically treated with a combination of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and azithromycin. On the next dayLegionella serogroup 1 urinary antigen was positive. All other microbiologic exams were negative. Treatment with azithromycin was continued for 14 days. All symptoms and dysfunctions improved gradually and he was discharged after eight days of hospitalization. The public health authorities conducted an epidemiologic investigation, but did not found any outbreak or the source of disease.

Follow-up at one month showed complete resolution of the neurologic deficits. Radiologic and analytic abnormalities were also resolved by this time, and seroconvertion IgM/IgG of Legionella serology was also identified.

Discussion

There are no available data about worldwide incidence of Legionellosis. In Europe, 4546 cases were reported in 2004.9 In Portugal, as in Europe, notified cases of LD have been increasing in the last years.10,11 However, it is thought that this disease remains underdiagnosed and underreported.11

A study carried out in Portugal between 2000 and 2006, showed that 84,5% of Legionellosis was caused by L. pneumophila. Serogroup 1 was identified in 53,2% of cases, only slightly higher as the frequency of serogroups 2-14 (46,8%).12 This is important because soluble Legionella antigen in urine only detects serogroup 1, leading to false negative results in infections caused by other serogroups.13 In this case, urinary antigen test combined with culture of lower respiratory tract sputum is considered the best testing diagnosis strategy.13

Epidemiological context is also important to detect a possible outbreak. In Portugal, a statistical study carried out between 2000 and 2006, based on the portuguese notification program, showed that water contamination by Legionella is more frequent in thermal (31%), companies and buildings (31%), hotels (19%) and hospitals (10%).12

L. pneumophila is a major cause of community-acquired and nosocomial pneumonia, accounting for 2 to 15% of pneumonias requiring hospitalization.14 Patients can present with respiratory symptoms (cough, chills, fever, dyspnea) and gastrointestinal symptoms are often prominent (diarrhea, vomiting). The central nervous system (CNS) can also be involved, with a broad spectrum of symptoms ranging from confusion to coma.8 Although rare, cerebellar dysfunction is well documented. Shelburne et al reported 29 cases with cerebellar dysfunction and the most frequently reported symptoms were dysarthria and ataxia (79% and 72%, respectively).15 The average time from the onset of respiratory symptoms to the neurological symptoms was 4,5 days.15 In this case, neurological and pulmonary symptoms started at the same time. The pathogenesis of neurological involvement in LD remains unclear. A possible mechanism is dissemination of the bacteria from a lung focus with direct invasion of the CNS. In the absence of direct invasion of CNS, a neurotoxin or an immune-mediated mechanism may be responsible.8,15

In this case, neurological symptoms were investigated through a head CT and MRI. In literature, 80% of the head CT as well as lumbar puncture are normal in LD with neurological symptoms.15 EEG can reveal diffuse slow-wave activity consistent with toxic encephalopathy.15 Renal and hepatic dysfunction, thrombocytopenia and hyponatremia are also frequent in LD,16 as also observed in the case described.

Evidence based treatment for neurologic dysfunction in Legionella infection is supportive care and antibiotics (macrolides or respiratory tract quinolones). Some authors tried high doses of corticosteroid but there are no reliable evidence supporting this treatment.15 Only one case report documented the use of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy with a rapid and almost complete resolution of neurological symptoms.17

In Europe the overall rate of Legionella mortality is around 12%.9 Prognosis of neurological deficits is not well established due to the limited number of cases and the lack of prospective studies. Shelburne et al followed 17 patients with neurological dysfunction, for three years, 29% recovered completely but 71% persisted with dysarthria or ataxia. Other authors emphasize that neurological deficits are rare in Legionella infection and tend to persist for long periods.8 In this case, patient improved quickly after institution of antibiotic therapy, with complete recovery. The authors presume that an early antibiotic therapy helped in this rapid neurological improvement.

In conclusion, the authors report a case of LD with a rare presentation, with an unusual quick and full recovery. Pneumonias with atypical symptoms should undergo through combined etiology investigation with urine antigen test, respiratory tract sputum cultures and serology, since others serogroups besides group 1 have relevant prevalence. As LD can be a public health problem, its diagnosis and notification have important social impact.

Quadro I

Abnormal laboratory data

| Results | Reference values | |

| White blood cell | 5 875/mm3 | (40 000 - 11 000) |

| Neutrophlis | 84,7% | (40,0 - 75,0) |

| lymphocytes | 11,1% | (20,0 - 45,0) |

| Platelets | 112 000/mm3 | (150 000 - 400 000) |

| C-reactive | 393 mg/L | (0,0 - 5,0) |

| Sodium | 132 mmol/L | (135 - 145) |

| Potassium | 2,82 mmol/L | (3,5 - 5,0) |

| Creatinine | 1,24 mg/dL | (0,7 - 1,2) |

| Lactate dehydodrogenase | 423 U/L | (135 - 225) |

| Aspartate transaminase | 203 U/L | (10 - 34) |

| Alanine transaminase | 114 U/L | (10 - 44) |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 88 U/L | (45 - 122) |

| Gamaglutamiltransferase | 89 U/L | (10 - 66) |

| Creatine kinase | 776 U/L | (24 - 204) |

Figura I

Chest x-ray: consolidation pattern in the right lower lobe.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1.Fraser DW, Tsai TR, et al. Legionnaires´ disease: description of an epidemic of pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1977 Dec; 297(22): p. 1189-1197.

2.Ginevra C, Duclos A, Vanhems P, et al. Host-related risk factors and clinical features of community-acquired legionnaires disease due to the Paris and Lorraine endemic strains. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Jul; 49(2): p. 184-191.

3.Ricketts KD, Joseph CA, European Working Group for Legionella Infections. Legionnaires disease in Europe: 2005-2006. Euro Surveill. 2007 Dec; 12(12): p. 7-8.

4.Benson RF, Fields BS. Classification of the genus Legionella. Semin Respir Infect. 1998 Jun; 13(2): p. 90-99.

5.UptoDate. [Online].; 2016 [cited 2016 April 14. Available from: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-and-pathogenesis-of-legionella-infection.

6.Yu VL. Cooling towers and legionellosis: a conundrum with proposed solutions. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2008 Jul; 211(3-4): p. 229-234.

7.Correia AM, Gonçalves J, Gomes JP, et al. Probable Person-to-Person Transmission of Legionnaires´ Disease. N Engl J Med. 2016 Febr; 374(5): p. 497-498.

8.Mandell G, Bennett J, Dolin R. In Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed.: Churchill Livingstone; 2015. p. 2633-2644.

9.Johnson J, Raff M, Arsdall J. Neurologic Manifestations of Legionnaires´ Disease. Medicine. 1984; 63(5): p. 303-310.

10.Bartram J, Chartier Y, Lee JV, et al. Legionella and the prevention of legionellosis: World Health Organization; 2007.

11.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Legionnaires disease in Europe 2010. Stockholm: ECDC. 2012.

12.Direcção-Geral da Saúde. Programa de Vigilância Epidemiológica Integrada da Doença dos Legionários: Notificação Clínica e Laboratorial de Casos. [Online].; 2004 [cited 2016. Available from: https://www.dgs.pt/doenca-dos-legionarios/informacao-para-profissionais/orientacoes-tecnicas/circular-normativa-n-5dep-de-22042004-pdf.

13.Mansilha CR, Coelho CA, Reinas MA, et al. Prevalência da Legionella pneumophilaem águas de diferentes proveniências das regiões Norte e Centro de Portugal no período de 2000 a 2006. Rev Port Saúde Pública. 2007; 25(2): p. 65-80.

14.Murdoch DR. Diagnosis of Legionella Infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003 Jan; 36(1): p. 64-69.

15.Murder R, Yu V, Fang G. Community-acquired Legionnaires´ Disease. Semin Respir Infect. 1989 Apr; 4(1): p. 32-39.

16.Shelburne SA, Kieholfner MA, Tiwari PS. Cerebellar involvement in legionellosis. Southern Medical Journal. 2004 Jan; 97(1): p. 61-67.

17.Sauchelli D, De Pascale G, Scoppettuolo G, et al. Neurological involvement during legionellosis, look beyond the lung. J Neurol. 2012; 259(10): p. 2243-2245.