INTRODUCTION

Pylephlebitis is a rare (incidence of 2.7/100,000 per year) and potentially fatal (mortality up to 25%)1 clinical condition characterized by thrombosis of the portal vein induced by an intra-abdominal infection. Diagnosis is often delayed due to the nonspecific nature of the symptoms, which may include abdominal pain, fever, chills, weakness, nausea and vomiting. Jaundice and hepatic lesion may occur in advanced stages of the disease. This condition should be considered in cases of sepsis with a suspected abdominal origin.2 The most common infection associated with pylephlebitis is diverticulitis, representing almost a third of cases. Appendicitis, cholecystitis, cholangitis are also common associations, while the inflammatory bowel disease and pancreatitis are predisposing factors in a small portion of cases. The bacteremia is often typically polymicrobial with Bacteroides fragilis, Escherichia coli and Streptococcus spp being the most common microorganisms.3 Treatment is based on antibiotic therapy. Anticoagulation can be used in some cases in order to prevent further thrombus extension.4-6

CASE REPORTA 65 year old woman presented to the emergency department with fever (39ºC), diffuse abdominal tenderness, nausea and vomiting, anorexia and marked asthenia with 2 weeks of duration. She had a history of hypertension and depressive syndrome, denying smoking, alcohol, intravenous drug use or previous surgeries, while having no relevant family history. Her usual prescription was bisoprolol 10 mg/day, amitriptyline 50 mg/day and lorazepam 1 mg/day. On physical examination the patient was restless, febrile (38,5ºC), hypotensive (90/59 mmHg), tachycardic (105 bpm), eupneic with peripheral arterial saturation of 95%, with a diffuse abdominal tenderness on palpation with guarding, without any identifiable masses or organomegaly.

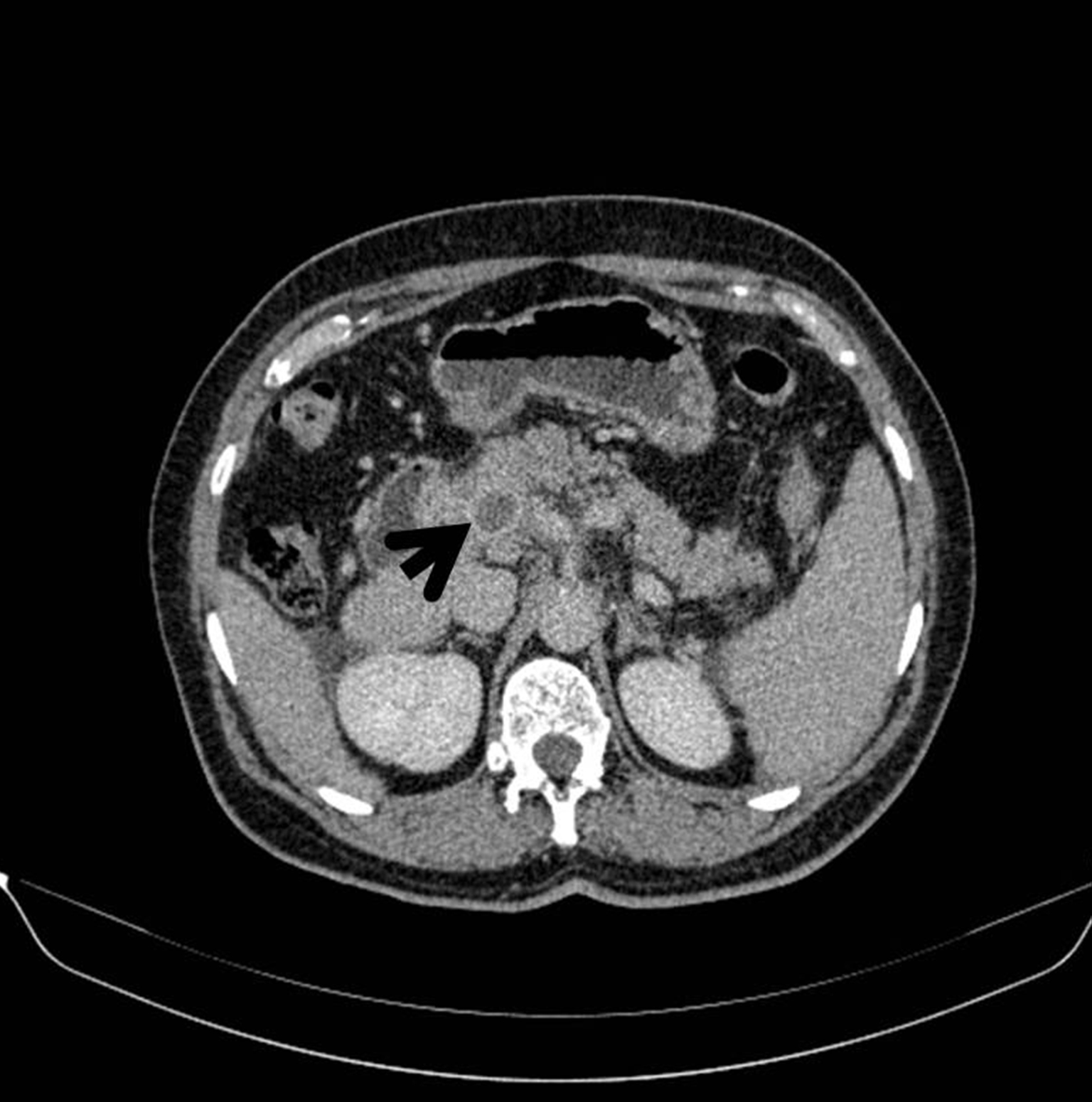

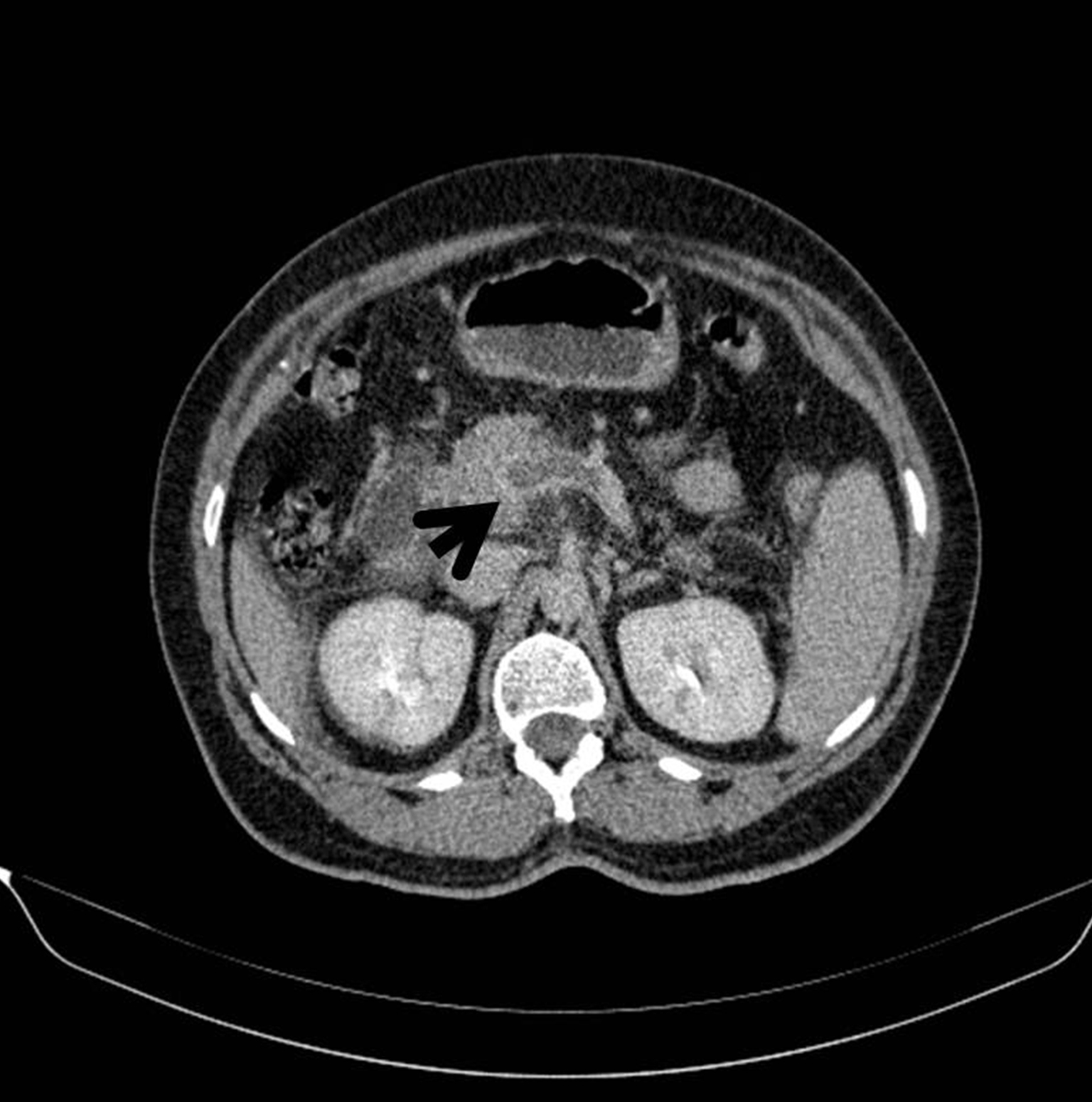

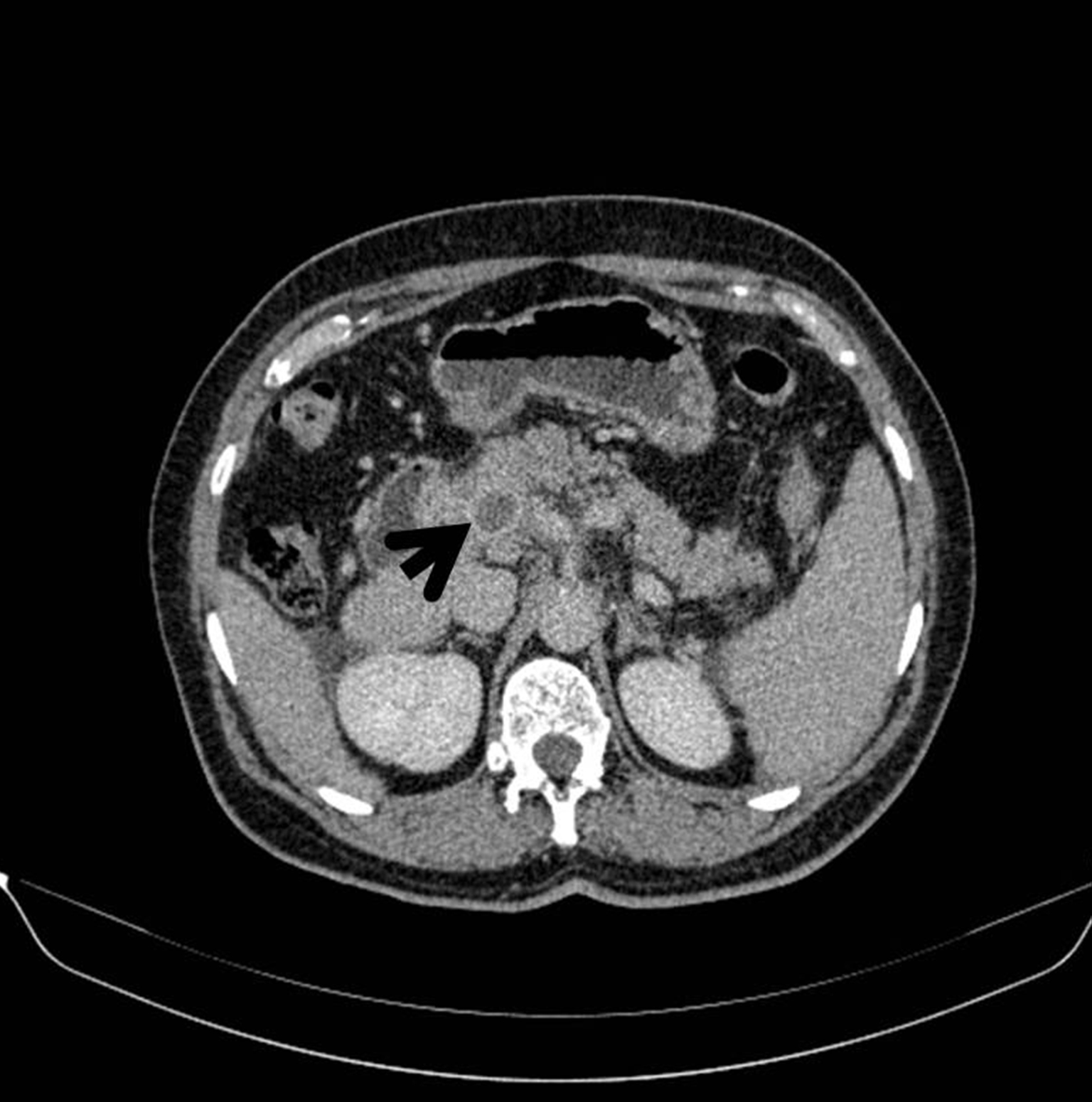

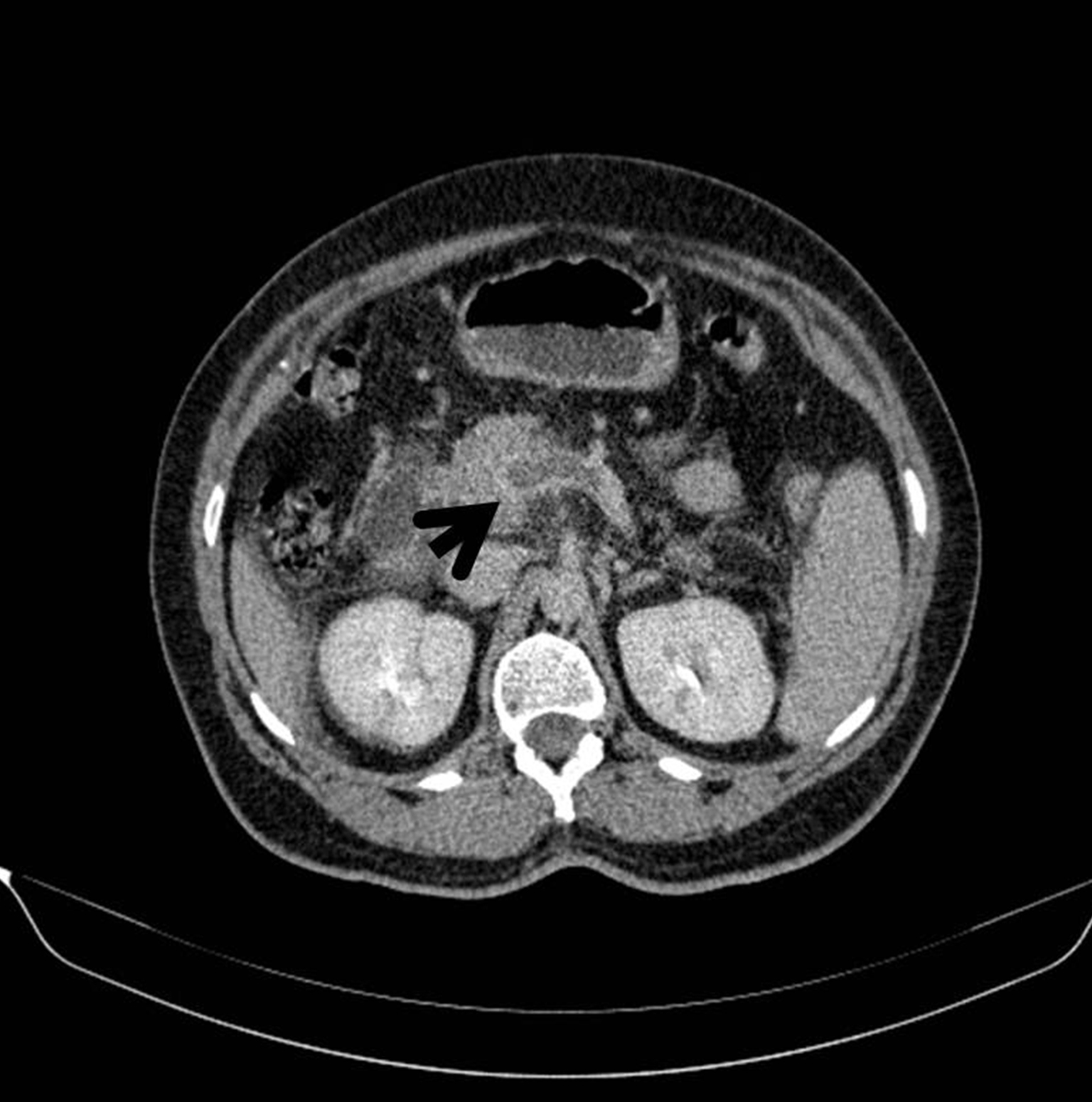

Initial laboratory testing showed a normochromic normocytic anemia 9.1 g/dL (N: 13.0-17.0), leukocytosis 16.7x109/L (N: 4.0-10.0) with neutrophilia 83.6% (N: 40-80), increased C-reactive protein 35.2 mg/dL (N: <0.5) and d-Dimers 11.5 µg/mL (N: <0.3), with no other changes including coagulation, markers of liver or kidney function. Arterial blood gasometry, urinalysis and chest radiography presented no changes. Due to a likely abdominal sepsis, a Thoracic-Abdominal-Pelvic CT scan was made and identified portal thrombosis with extension to the right portal branches and superior mesenteric vein, homogeneous splenomegaly, diverticular disease without apparent diverticulitis, peritoneal effusion, as well as mesenteric, peripancreatic, and perihepatic lymphadenopathy. (Fig.1-2).

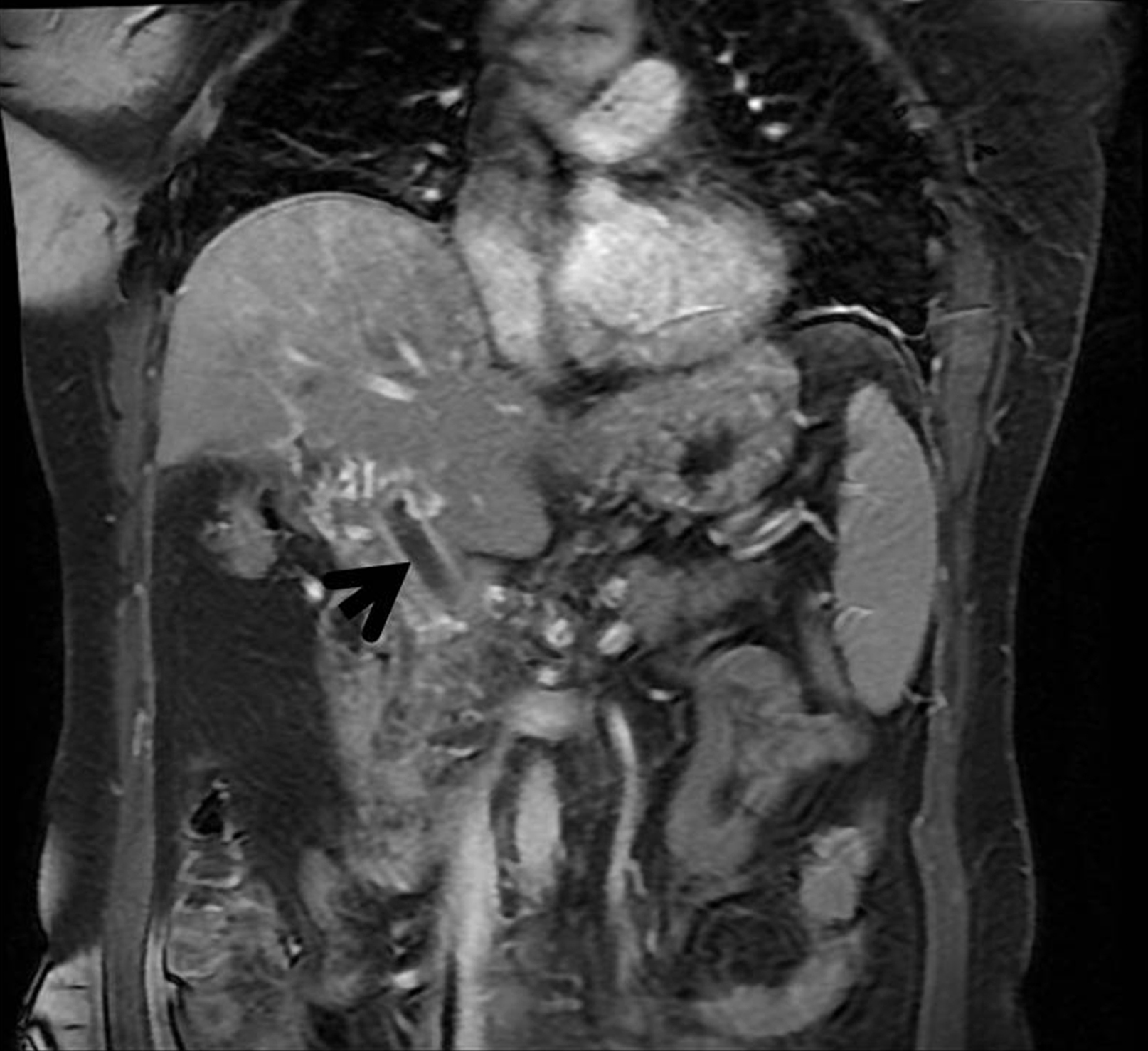

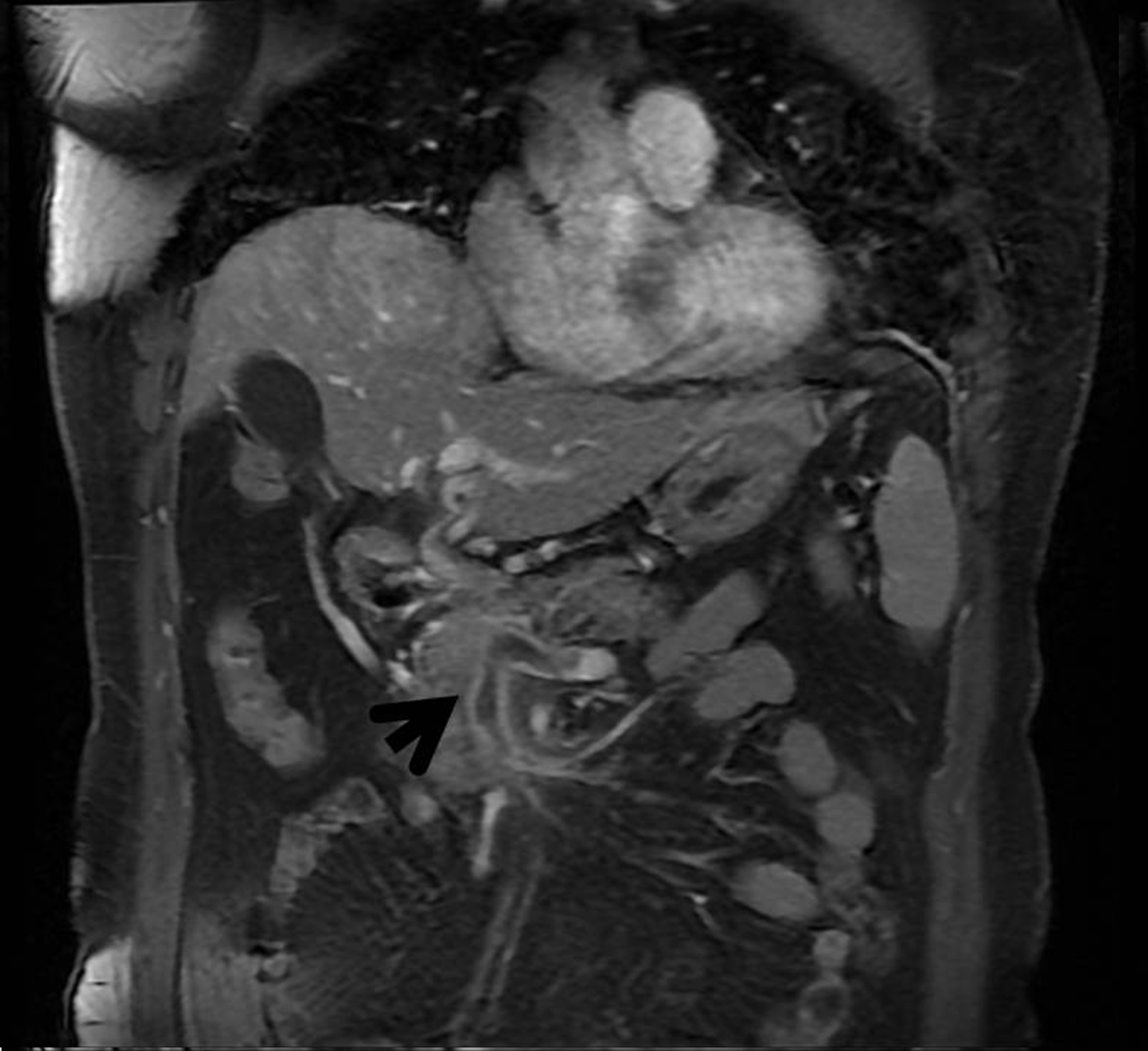

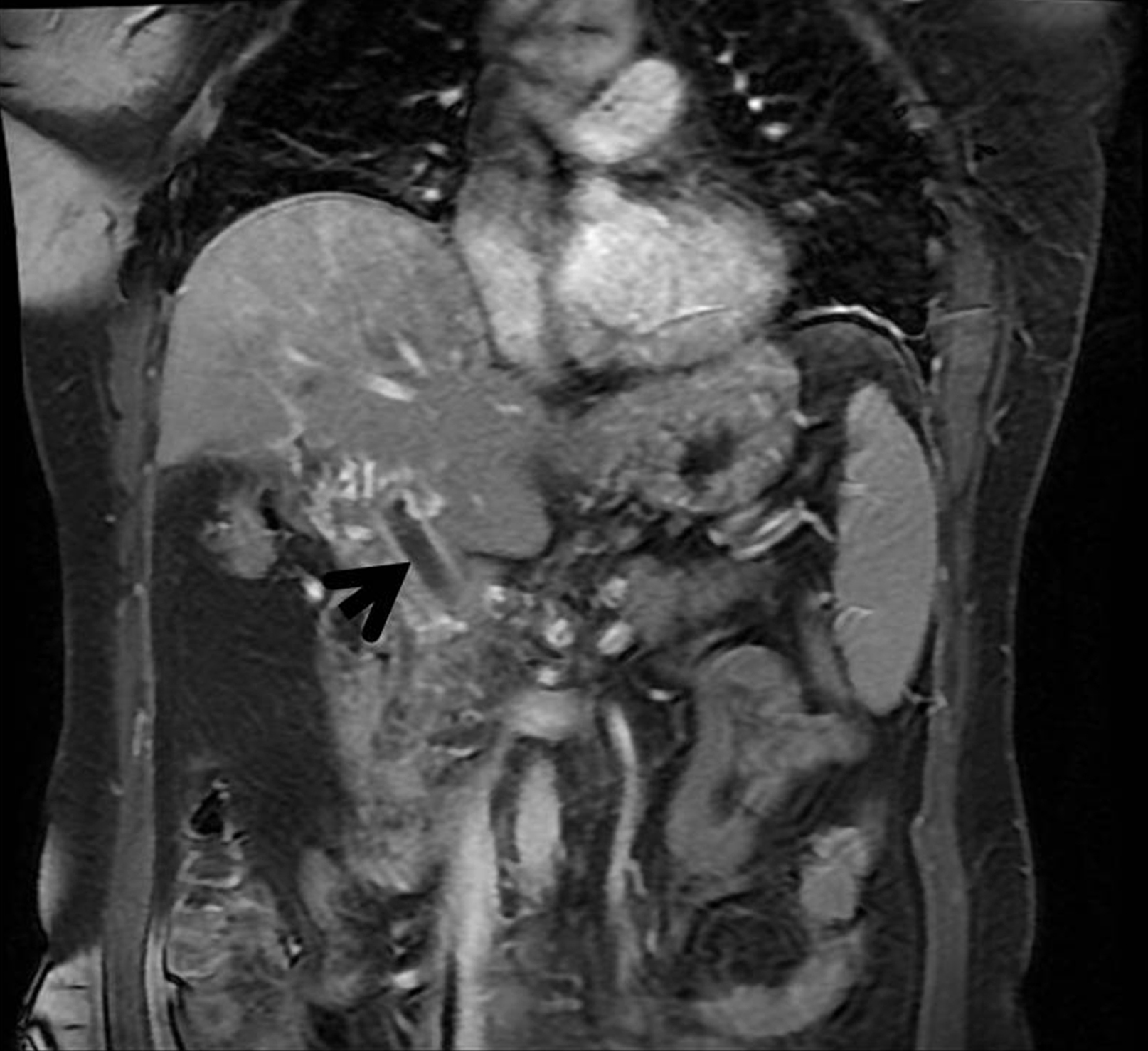

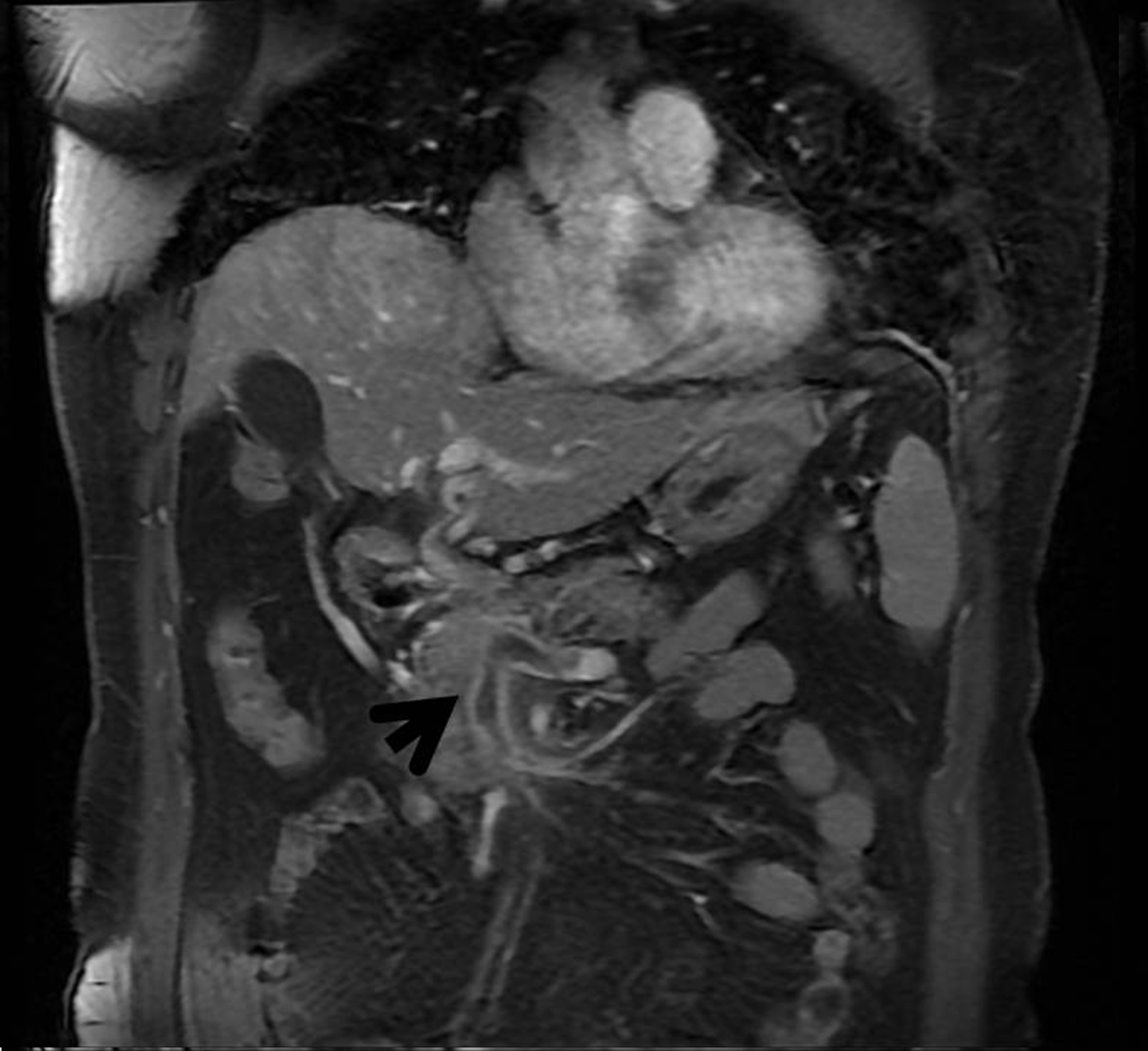

Diagnosis of septic thrombosis of the portal vein (pylephlebitis) was assumed and empirical antibiotic therapy was started with meropenem and vancomycin. During hospitalization subsequent investigation was negative for viral B and C Hepatitis, HIV, Epstein-Barr virus, Cytomegalovirus and Treponema pallidum. Protein electrophoresis showed polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, and immunophenotyping of peripheral blood had no abnormalities. 4 blood cultures were negative (under antibiotic). An abdominal Magnetic Resonance confirmed the venous thrombosis, with extension to the splenic vein. (Fig. 3-4). Colonoscopy identified simple diverticulosis.

The patient remained febrile (38°C) during the first week of hospitalization, with subsequent resolution, as well as full regression of the gastrointestinal symptoms. Due to thrombosis extension, anticoagulation therapy was started with enoxaparin, with subsequent switch to warfarin. Patient was discharged on the 15th day of hospitalization after clinical stability and inflammation parameters normalization, with switch of intravenous antibiotic therapy already described for ciprofloxacin and metronidazole.

The patient fulfilled 2 additional weeks of oral antibiotics and 6 months of oral anticoagulation. An abdominal angio-CT was performed at 6 months post-discharge, which revealed cavernous transformation of the portal and mesenteric veins, with establishment of collateral circulation. A prothrombotic study was conducted after cessation of warfarin, which showed 200% elevation of functional factor VIII, with no further changes (normal levels of fibrinogen, negative lupus anticoagulant, anti-cardiolipin and anti-Beta-2-Glycoprotein antibodies). An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed with identification of one duodenal diverticulum, although there was no evidence of infection at the time. After 12 months of follow up the patient is completely asymptomatic.

DISCUSSIONPylephlebitis is a rare diagnosis that should be considered whenever a patient has a septic state with abdominal starting point. Despite low incidence, high mortality makes its exclusion a pressing matter. The predominant symptoms are asthenia (95%), fever (86%), abdominal pain (82%) and nausea/vomiting (28%), all present in this case. Hepatomegaly (42%), splenomegaly (23%) and ascites (20,5%) are also possible findings, with the last two also identifiable in our patient. Elevated C-reactive protein and leukocytosis are common findings, usually present in complicated cases. Abdominal CT scan allowed the diagnosis and rapid therapeutic intervention. Despite serial blood cultures, microbiologic isolation was not possible. However it is important to note that due to the initial instability of the patient, blood cultures were taken only after clinical stabilization and the beginning of antibiotic treatment, which may have influenced the results. Detection of microorganisms by blood culture ranges from 42% to 88% according to the literature

2,3,6, being typically polymicrobial with

Bacteroides fragilis, Escherichia coli and Streptococcus spp the most common agents.3This condition is usually associated with an underlying abdominal infectious process. Most commonly associated conditions are diverticulitis (30%), appendicitis (19%), inflammatory bowel disease (6%), pancreatitis (5%) and gastroenteritis (4%)3. Colonoscopy revealed diverticulosis with no signs of inflammation, although performed after the beginning of antibiotics. In this case it was not possible to correctly identify the focus of the infection.

If pylephlebitis is suspected, management of predisposing intra-abdominal infection with antibiotics is mandatory. Empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics that cover anaerobic, gram-negative aerobic and gram-positive aerobic cocci should be administered immediately and subsequently modified according to culture results.1,6,7 In this case broad spectrum antibiotic with meropenem and vancomycin (specially for gram-positive aerobic agents) was prescribed in the first 2 weeks of treatment, to cover those potential agents and due to septic presentation at admission. When patient was hemodynamically stable and apirexia maintained, given the absense of microorganism isolation in blood cultures, antibiotic regimen was modified to an oral one with ciprofloxacin and metronidazole for another 2 weeks (regimen recommend in empiric treatment of complicated intra-abdominal infection of mild-to-moderate severity).7 There is no established recommendation on the duration of therapy, however several articles proposed a 4 weeks therapy duration, extending it to 6 weeks in cases of liver abscesses.1,9

Current use of anticoagulation in pylephlebitis is controversial. While some advice against its use in limited thrombosis, it may play a role in prevent or even reverse the extension of thrombi and their complications, purposed for a 3 to 6 months duration in case of absence of hypercoagulability.2 In a study of 100 patients with pylephlebitis, those undergoing anticoagulation showed better results, particularly in the mortality rate, in the venous recanalization rate and in the prevention of development of portal hypertension.3,9 In this case it was decided to initiate anticoagulation due to the large extension of the thrombosis and maintenance of fever during the first week of treatment.

In conclusion pylephlebitis should not be forgotten in patients with abdominal sepsis without identifiable cause, as this disease continues to have a high mortality rate, especially if untreated. Timely diagnosis is essential for the initiation of antibiotic therapy and anticoagulation, which can lead to a more favorable outcome.

Figura I

Abdominal CT: Portal thrombosis and mesenteric thrombosis.

Figura II

Abdominal CT: Portal thrombosis and mesenteric thrombosis.

Figura III

Magnetic Resonance: coronal section with portal thrombosis, superior mesenteric and esplenic vein thrombosis.

Figura IV

Magnetic Resonance: coronal section with portal thrombosis, superior mesenteric and esplenic vein thrombosis.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Wong K, Weisman DS, Patrice KA. Pylephlebitis: a rare complication of an intra-abdominal infection. Journal of community hospital internal medicine perspectives 2013; 3(2).

2. Choudhry A, Baghdadi Y, Amr M, Alzghari M, Jenkins D, Zielinski M. Pylephlebitis: a Review of 95 Cases. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2016; 20(3): 656–661.

3. Kanellopouloua T, Alexopouloua A, Theodossiadesb G, Koskinasa J, Archimandritisa A. Pylephlebitis: an overview of non-cirrhotic cases and factors related to outcome. Scandinavian journal of infectious diseases. 2010; 42(11-12):804-11.

4. Ponziani F, Zocco M, Campanale C, Rinninella E, Tortora A, Di Maurizio L, et al. Portal vein thrombosis: Insight into physiopathology, diagnosis, and treatment. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010; 16(2), p.143.

5. Chawla Y, Bodh V. Portal Vein Thrombosis. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hepatology. 2015; 5(1), pp.22-40.

6. Plemmons RM, Dooley DP, Longfield RN. Septic thrombophlebitis of the portal vein (pylephlebitis): diagnosis and management in the modern era. Clin Infect Dis. 1995; 21(5): 1114-20.

7. Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Bradley JS, Rodvold KA, Goldstein EJ, Baron EJ. Diagnosis and Management of Complicated Intra-abdominal Infection in Adults and Children: Guidelines by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2010; 50:133–64.

8. Pérez-Bru S, Nofuentes-Riera C, García-Marín A, Luri-Prieto P, Morales-Calderón M, García-García S. Pileflebitis: una extraña pero posible complicación de las infecciones intraabdominales. Cirugía y Cirujanos. 2015; 83(6), pp.501-505.

9. Falkowski AL, Cathomas G, Zerz A, Rasch H, E.Tarr Pl. Pylephlebitis of a variant mesenteric vein complicating sigmoid diverticulitis. Journal of radiology case reports 2014; 8(2):37-45.