Introduction

Xanthomas are lipid deposits in the skin and tendons, occurring in the setting of primary or secondary disorders of lipid metabolism (1). Although dyslipoproteinemias are common, only a minority of patient will develop cutaneous xanthomas (1).

Dyslipoproteinemias are classified as primary conditions (genetically determined and categorized by Fredrickson into six types according to specific lipoprotein elevation) or as secondary conditions (in the context of another disease, for example, hypothyroidism, Diabetes mellitus, obesity, nephrotic syndrome)(2) (3).

Certain types of xanthomas may suggest the underlying lipid abnormality, however, none is absolutely specific and work up is always required (3). There are different types of xanthomas: xanthelasma, eruptive, plane, tuberous and tendinous (3).

Eruptive xanthoma is characterized by yellow papules with a red halo around the base that appear suddenly on extensor surfaces of the arms, legs, and buttocks, suggesting severe hypertriglyceridemia (3). Severe hypertriglyceridaemia is associated with a substantial increase in long term cardiovascular risk and total mortality (4). Although rare, hypertriglyceridemia is a well-known cause of acute pancreatitis (5). When triglycerides are above 900 mg/dL, chylomicrons in circulation are large enough to occlude the pancreatic capillaries leading to ischemia (6). Furthermore, hypertriglyceridemia is associated with an increase in plasma viscosity (chylomicronemia syndrome) which may contribute to memory loss, dyspnea, lipemia retinalis and paresthesias (7).

Case ReportWe present a 25-years old Caucasian female admitted with eruptive cutaneous lesions located on the buttocks and scapulae. Simultaneously with the onset of skin lesions, the patient referred asthenia and sporadic headaches. She had no complaints of dyspnea, chest pain, intermittent claudication or abdominal pain. There was no history of smoking or alcohol consumption and she did not use hormonal contraception. Three years before she presented to the Emergency Service with a peripheral facial nerve palsy. Hypertriglyceridaemia was diagnosed in her mother and her mother’s sister. She also had a cousin with Diabetes mellitus. Her younger brothers (dizygotic twins) were healthy.

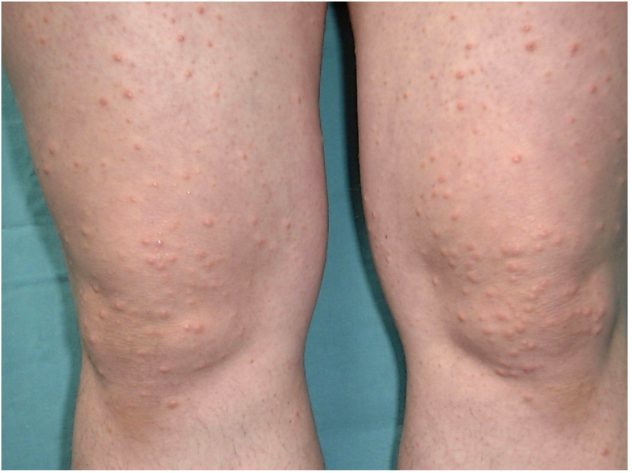

Physical examination showed an obese female (body mass index was 30 Kg/m2 and the waist/hip relationship 0,83). There was no corneal arch, no audible carotid murmurs and the thyroid wasn’t palpable. Blood pressure was 120/85 mmHg and cardiopulmonary auscultation was normal. Palpation of the abdomen did not elicit pain or discomfort but the liver was palpable (~1,5 cm beneath the ribs). The limbs showed no morphological alterations and the pulses were symmetric. No peripheral lymphadenopathy was detected. Fundoscopy was also normal. On dermatological examination, lesions were pink-orange papules, firm and elastic, with 1-2 mm diameter, well circumscribed, on the scapular regions, buttocks, thighs and arms (Figure 1).

The most important differential diagnosis were eruptive xanthomas versus sarcoidosis (Granuloma annulare). Workup revealed triglycerides 3320 mg/dL, total cholesterol 305 mg/dL, fasting blood glucose 92 mg/dL, gamma-glutamyltransferase 55 U/L (<49), alanine transaminase (ALT) 85 U/L (< 43), aspartate transaminase (AST) 45 U/L (< 40). Blood cell counts, coagulation, uric acid, urea and creatinine showed no alterations and proteinuria was excluded. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme was normal as well as serum and urinary calcium levels.

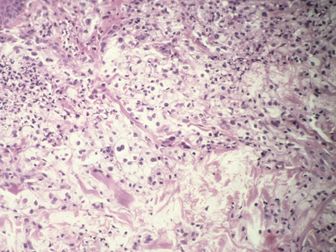

Histological examination of the skin biopsy detected “clearly demarcated nodular lesions located on the upper and intermediate zones of the dermis, constituted mainly by histiocytes from a xanthomised cytoplasm making possible the xanthoma diagnosis” (Figure 2).

Serologic markers for hepatitis B and C were negative. Protein electrophoresis and thyroid hormone levels were normal. Oral glucose tolerance test showed an impaired glucose tolerance (fasting blood glucose 103 mg/dL and 2-hour plasma glucose 160 mg/dL).

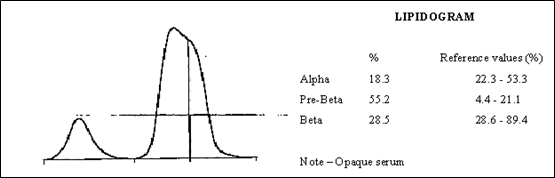

Laboratory measurement of lipids and lipoproteins are expressed in Table 1. Lipidogram showed a pre-beta fraction increase of 55,2% (4,4-23,1%) (Figure 3).

The study was completed with an ECG (sinus rhythm ± 84 beats per minute, normal pattern) and an abdominal ultrasound that revealed diffuse hepatic steatosis with a homogeneous moderate splenomegaly.

Treatment with micronized fenofibrate was started with 200 mg per day and the patient was recommended a diet low in fat and carbohydrates. A fast decrease in triglycerides levels and subsequent disappearance of the skin lesions was achieved, just as the headache and asthenia disappeared.

After two months under fenofibrate therapy, the patient presented an urticarial exanthema, which was considered to be an adverse effect of fibrate therapy. Due this, the medication was withdrawn. One week later, therapy was resumed, this time without cutaneous manifestations.

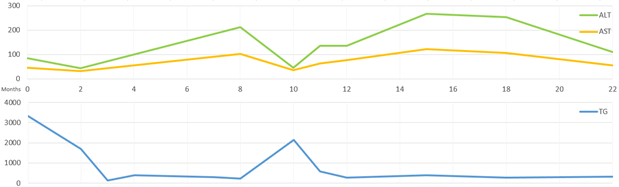

At 8th month, fibrate therapy was again suspended, for two months, due to a rise in transaminases levels (ALT nine-fold and AST three-fold over normal values). This interruption led to a marked elevation of triglycerides levels (with normalization of transaminases).

At 10th month, when enzyme levels were normal, fenofibrate was restarted. Although liver enzymes increased again was decided to go on with fenofibrate, keeping the under monthly analytical surveillance. After one year, liver enzymes normalized.

Graphic 1 shows the evolution of triglycerides and transaminases over 22 months.

Discussion

Eruptive xanthomas are not only an aesthetical problem but they can represent an important underlying systemic disease.

In this patient, obesity, unhealthy diet and sedentary lifestyle were responsible for hypertriglyceridaemia. Although a history of hypertriglyceridaemia on her mother´s family was present, no further workup was possible because they refused. Furthermore, given the good response to pharmacological therapy and dietary intervention, a primary hypertriglyceridaemia was presumed.

The patient’s initial lipid profile (marked hypertriglyceridaemia and moderate hypercholesterolemia) and the laboratory conclusion about a “milky serum”, suggestive of chylomicronemia, accounted for the execution of a lipidogram and the request for ApoE (E3 E4) genotyping. The lipidogram showed a fair elevation of the pre-beta fraction (VLDL) without clear evidence of existing chylomicra. Unfortunately, the lipidogram was performed after starting the pharmacological therapy, which could adversely affect the results. A short therapeutic stop could have been an alternative to avoid this bias. ApoE (E3 E4) genotyping excluded a type III dyslipidaemia according to the Fredrickson/WHO classification (2). According to the same classification, these data allowed us to classify as a type V phenotype(2).

Hypertryglyceridaemia is an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis. Plasmatic triglycerides levels represent in part concentration of the triglyceride-carrying lipoproteins: VLDL, chylomicrons and their remnants. Although chylomicrons and probably VLDL are both too large to penetrate the arterial wall, their remnants are small enough to do this, and they contribute to atherosclerotic plaques (8). Furthermore, hypertryglyceridaemia is commonly associated with a reduction in HDL and an increase in LDL levels (4). The most common form of hypertriglyceridemia are related to overweight and sedentary lifestyle (9).

This patient presented simultaneously increased morbidity and mortality due high cardiovascular risk and also high risk of pancreatitis (severe hypertriglyceridemia) which made the therapeutic intervention imperative.

Management of hypertriglyceridemia should begin with risk assessments to aid in treatment decisions. In this case, triglycerides were “very high” (≥ 500 mg/dL) so it was fundamental to intensify weight management, physical activity and prevent pancreatitis with a fibrate. According to recommendations, when triglycerides are below 500 mg/dL it is important to turn to LDL-lowering therapy (goal treatment is triglycerides below 150 mg/dL) (9).

Fibrates generally are well tolerated, however, they can be associated with some adverse effects which de most common are myopathy, liver enzyme elevations and cholelithiasis (10). Skin rashes are rare but can occur in 2% of the cases (5).

Conclusion

Some systemic diseases can present with cutaneous manifestations, which can be an early sign. Therefore, it is important to recognize those dermatological symptoms in order to diagnose and treat properly, so we can avoid related morbidity.

Quadro I

Measurement of lipids and lipoproteins.

| Ref. Value | ||

| ApoA | 132 mg/dl | 101 - 198 |

| ApoB | 127 mg/dl | 60 - 126 |

| ApoE | 7,5 mg/dl | 2,3- 6,3 |

| ApoE phenotype | E3, E4 | |

| Lipoprotein (a) | 8,0 | 0,0-30,0 |

| pre-beta fraction | 55,2% | 4,4-21,1% |

Figura I

Pink-orange papules, firm and elastic, with 1-2 mm diameter and well circumscribed.

Figura II

Skin biopsy: histiocytes from a xanthomised cytoplasm.

Figura III

Lipidogram showing a significant increase in pre-beta fraction.

Figura IV

Triglycerides (TG - mg/dL) and transaminases (AST- aspartate aminotransferase; ALT- alanine aminotransferase (U/L)) evolution over 22 months.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Massengale WT, Hodari KT, Boh EE, Nesbitt LT. Xanthomas. In Dermatology.: Elsevier ; 2012. p. 1547-1555.

2. World Health Organization Memorandum. Classification of Hyperlipidemias and Hyperlipoproteinemias. Circulation. 1972.

3. Habif TP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal disease. In Clinical Dermatology.: Elsevier; 2016. p. 986-1008.

4. Tenenbaum A, Klempfner R, Fisman EZ. Hypertriglyceridemia: a too long unfairly neglected major cardiovascular risk factor. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2014; 13(159).

5. Catapano AL, Graham I, Backer GD, et al. 2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias The Task Force for the Management of Dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Atherosclerosis. 2016;: p. 281-344.

6. Kota SK, Kota SK,Jammula S, Krishna SVS, Modi KD. Hypertriglyceridemia-induced recurrent acute pancreatitis: A case-based review. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 16(1): p. 141–143.

7. UpToDate. UpToDate. [Online].; 2017 [cited 2017 Feb. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/hypertriglyceridemia.

8. Deedwania P, Barter P, Carmena R, Fruchart JC, Grundy SM, Haffner S, et al. Treating to New Targets Investigators: Reduction of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with coronary heart disease and metabolic syndrome: analysis of the Treating to New Targets study. Lancet. 2006; 368: p. 919-928.

9. Jellinger PS, Handelsman Y, Rosenblit PD, et al. Guidelines for management of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Endocr Pract. 2017; 23.

10. Davidson MH, Armani A, McKenney JM, Jacobson JA. Safety Considerations with Fibrate Therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2007; 99: p. 3C-18C.