Introduction

Extra-gonadal germ cell tumours (GCTs), defined by the absence of a primary neoplastic lesion at the ovaries or testis, represent 1-5% of all GCT.1These are usually diagnosed on the first decades of life (between the 2nd and 5th decades) and their most frequent location is the mediastinum 2but they can also appear on other midline structures (like the retroperitoneum and the central nervous system).3Malignant histological findings vary and include seminoma/dysgerminoma and non-seminoma/non dysgerminoma patterns (like mature teratoma, immature teratoma, yolk sac tumor, embryonal carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, and mixed GCT).1Clinical manifestations are associated with compression and invasion of mediastinal structures.4The term “teratocarcinoma” is used when teratomas are associated with embryonal carcinoma tissue. They usually occur in young men, aged between 15 and 35 years5, and are less frequent than seminomas or teratomas. Prognosis of extra-gonadal GCTs is generally poor, with 5-year survival rates of approximately 40 to 45%6,7. The authors present a case of a primary mediastinal teratocarcinoma that was diagnosed in an elderly patient, followed by a literature review about this subject.

Clinical case

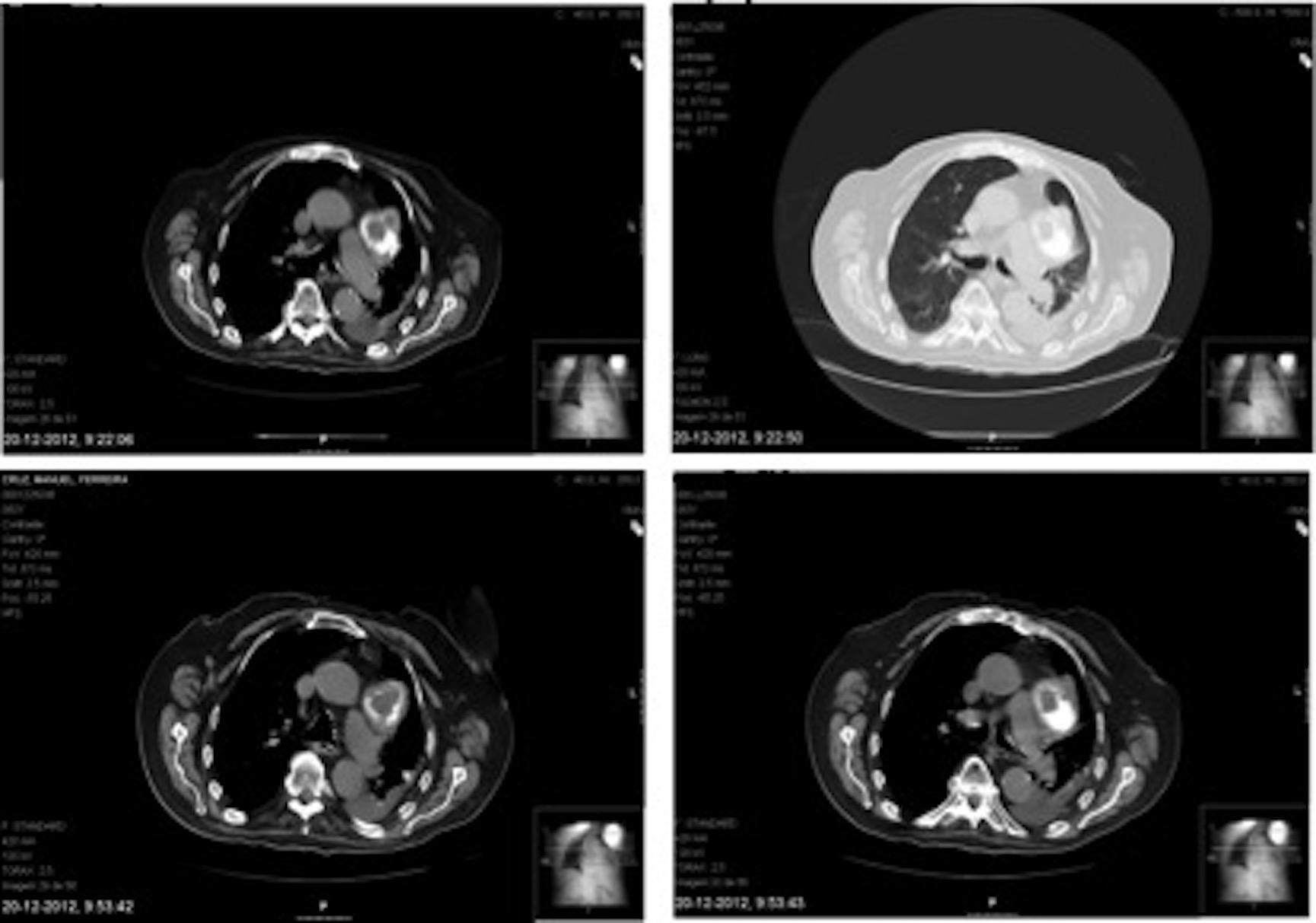

83-year old male patient, with type-2 diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, Parkinson´s disease and Karnofsky Performance Status Scale score of 50%, admitted for treatment of sepsis after a urological procedure. At admission, the patient also complained of dry cough with some weeks of duration, without any other cardiopulmonary, general and constitutional symptoms. Physically, the patient appeared unwell, with some loss of muscle mass and pulmonary auscultation revealed inspiratory crackles in the left hemithorax. Vital signs registration showed a slight tachycardia and peripheral oxygen desaturation, which was characterized as type 1 respiratory insufficiency by arterial blood gases measurement. His initial blood workup documented leukocytosis with neutrophilia, C-reactive protein elevation, mild hyponatremia, and his chest X-ray showed diffuse left lung opacities and a mediastinal enlargement (Fig. 1).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa was identified in blood and urine cultures. The initial interpretation was that the patient was suffering from nosocomial urinary sepsis, with secondary pneumonia due to the Pseudomonas bacteriemia. The patient was treated with fluids and piperacillin-tazobactam, with rapid improvement. Despite this fact, he kept a persistent dry cough and type 1 respiratory insufficiency.

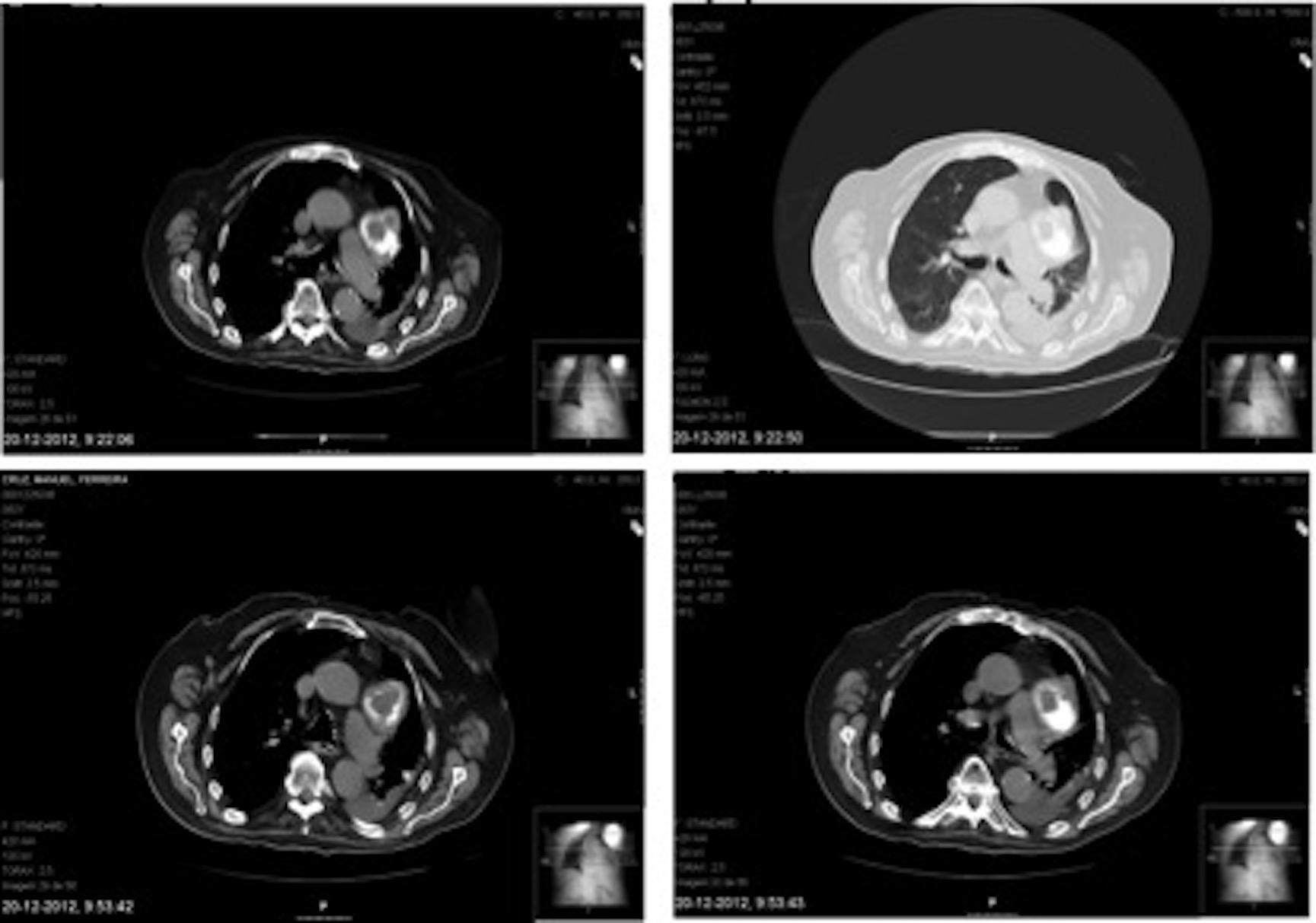

A thoracic CT-scan showed a left antero-lateral lobulated mediastinal mass (68mm), near the left pulmonary artery, with heterogeneous density and extensive calcified, quistic and soft tissue components (Fig. 2), bilateral pulmonary nodules and left pulmonary atelectasis.

The next diagnostic steps were discussed with the patient and his family. A bronchofibroscopy was performed, with aspiration of abundant bronchial secretions and improvement of the atelectasis, there were no signs of any endobronchial masses or external compression and no tissue sample was collected. Next, a transthoracic CT-guided biopsy was carried out, the obtained tissue sample revealed a mediastinal teratocarcinoma with cartilaginous and spinocelular carcinoma components. Beta-hCG levels were elevated and alpha-fetoprotein levels were normal. Testicular evaluation (physical examination and ultrasound) was performed and no masses or nodules were found. At this point, the pulmonary bilateral nodules were interpreted as probable metastases, without any possibility of biopsy due to their location.

The patient was evaluated in the Hospital´s Muldisciplinary Oncological Decision Group and considered unfit for surgery and chemotherapy. Exclusive symptomatic care was decided and a Palliative Care consultation was requested. The patient remained in the ward, developed progressive dyspnoea, cachexia and asthenia and died in the hospital, with all his symptoms well managed and with his family present at the time of death.

Discussion

Extragonadal GCTs are more frequent in young males, and should be considered in cases of histologically poorly differentiated or of unknown primary neoplasms (especially in young men with midline structure disease).8The aetiology of extragonadal GCTs is unknown.

The clinical spectrum of these tumours is related to their location and mainly dependent on invasion or compression of nearby structures. In the mediastinum, clinical manifestations can include cough, dyspnea, stridor, chest pain, dysphagia and superior vena cava syndrome.9 In this clinical case, the patient had dry cough for a few weeks and, at the time of his admission, also presented type 1 respiratory failure. Despite the fact that he had a respiratory infection and that pulmonary atelectasis developed, these clinical findings could not be fully explained by the initial diagnosis.

When the diagnosis of extragonadal GCTs is established, a primary gonadal neoplasia must be ruled out, at least by ultrasound techniques.10In this case report, it is legitimate to assume a primary mediastinal tumour, as no changes were found at the patient´s testis.

Extra-gonadal GCTs are associated with increased alpha-fetoprotein and beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) plasmatic levels.

Treatment options for teratocarcinomas usually include chemotherapy followed by surgery. The initial chemotherapy regimen usually is cisplatin based.8, 9, 11 If after chemotherapy the serum tumor marker normalized and a residual tumor mass persists surgery is mandatory. After surgery, two scenarios can arise: the residual mass is a teratoma or tissue necrosis and it is not necessary to perform any further treatment or the mass still contains residual malignant tissue and adjuvant chemotherapy must be prescribed. 8,9,11

Disease-free survival rate at 24 months is about 42% in patients receiving chemotherapy, with the best results being obtained in cases of surgical resection after systemic treatment associated with a reduction or normalization of tumour markers.12

The overall prognosis depends upon the type of lesion identified, its biological behavior and the extent of the disease at diagnosis. Non-seminoma histology, associated with the elevation of beta-hCG and the mediastinum as primary location are independent factors of poor prognosis.13

In conclusion, the atypical presentation of this case, due to the age of the patient and the rarity of the tumour itself, motivated the authors to present this case report. After searching online databases the authors only found a single case report.14The authors also wish to motivate readers to “think outside of the box” and to consider other diagnostic options when confronted with clinical findings that do not integrate well with the rest of the clinical picture.

Figura I

Figure 1 –diffuse opacities in the left lung and a mediastinal enlargement (chest x-ray)

Figura II

Figure 2 – left mediastinal mass with calcified, quistic and soft tissue componentes (chest CT)

BIBLIOGRAFIA

References

1. McKenney JK, Heerema-McKenney A, Rouse R V. Extragonadal germ cell tumors: a review with emphasis on pathologic features, clinical prognostic variables, and differential diagnostic considerations. Adv Anat Pathol. 2007 Mar;14(2):69 – 92.

2. Díaz Muñoz de la Espada VM, Khosravi Shahi P, Hernández Marín B, Encinas García S, Arranz Arija J a., Pérez-Manga G. Tumores germinales mediastínicos. An Med Interna. 2008; 25(5):241–3.

3. Benali HA, Allaoui M, Benmansour A, Elkhanoussi B, Benjelloun S. Extragonadal mixed germ cell tumor of the right arm : description of the first case in the literature. 2012;2–5.

4. Clara S, Clara V, Selar A, Hallazgo UN. Informe de caso. 2007;11(2):2– 4.

5. Artiles IG, Carlos J, Vásquez R, Adela II, Quevedo R, Pino PP. A propósito de un caso. 2012;71(1):36– 9.

6. Bokemeyer C, Nichols CR, Droz J-P, Schmoll H-J, Horwich A, Gerl A, et al. Extragonadal germ cell tumors of the mediastinum and retroperitoneum: Results from an international analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2002 Apr 1; 20(7):1864–73.

7. International Germ Cell Consensus Classification: a prognostic factor-based staging system for metastatic germ cell cancers. International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group. J Clin Oncol. 1997 Feb; 15(2):594–603.

8. Moran C, Suster S, Koss M, Primary Germ Cell Tumors of The Mediastinum. Cancer, 1997; 80: 699-707.

9. Liu et al. Management of the primary malignant mediastinal germ cell tumors: experience with 54 patients. Diagnostic Pathology 2014, 9:33.

10. Böhle A, Studer UE, Sonntag RW, Scheidegger JR. Primary or secondary extragonadal germ cell tumors? J Urol [Internet]. 1986 May [cited 2016 Mar 26]; 135(5):939–43.

11. Walsh G, Taylor G, et al. Intensive Chemotherapy and Radical Resections for Primary Nonseminomatous Mediastinal Germ Cell Tumors. Ann Tohorac Surg 2000; 69: 337-44.

12. Sakurai H, Asamura H, Suzuki K, Watanabe S, Tsuchiya R. Management of primary malignant germ cell tumor of the mediastinum. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004; 34(7):386–92.

13. Khurana K, Gilligan TD, Stephenson AJ. Management of poor-prognosis testicular germ cell tumors. Indian J Urol. Jan; 26(1):108–14.

14. Cox JD. Primary malignant germinal tumors of the mediastinum. A study of 24 cases. Cancer. 1975 Sep; 36(3):1162–8.