IntroductionMediastinal masses comprise a diverse group of neoplasms. Their particular location is crucial to narrowing the differential diagnosis. Tumors of the anterior mediastinum include thymoma, germ cell tumors, thyroid disease and lymphoma and represent about 50% of all mediastinal masses.1-2.

Primary mediastinal seminoma occurs mostly in males in their third decade and accounts for 25% of primary mediastinal germ cell tumors.3 It is an uncommon neoplasm, morphologically similar to its gonadal counterpart but with a possibly different biologic behavior considering its particular location.4-5 It is a slow growing, bulky tumour that invades nearby structures early in its growth process. Symptoms may reflect direct involvement and/or compression of adjacent structures. Superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS) is an uncommon presentation and occurs in only 10-20% of cases.5

Case ReportA 45 years-old male, ex-smoker for 6 years (21 pack-year), with no relevant medical history, presented to the emergency department with a 4-month history of compressive substernal pain, progressively worsening effort dyspnea and palpitations. On admission, he had shortness of breath and tachycardia. He reported no other associated symptoms namely fever, weight loss or night sweats.

On clinical examination, he was anxious, afebrile (auricular temperature of 37,4ºC), tachycardic, radial pulse rhythmic and regular with a rate of 104 bpm, acyanotic, tachypneic with a respiratory rate of 24 breaths/min and a peripheral oxygen saturation of 92% while breathing room air. His blood pressure was 132/70mmHg. Relevant findings on cervical and chest examination included venous distension. Pulmonary auscultation revealed decreased breath sounds over the right lung field with no adventitious sounds. We did not find peripheral lymphadenopathies nor hepatosplenomegaly. The neurologic exam was normal. The remainder of the physical examination was noncontributory.

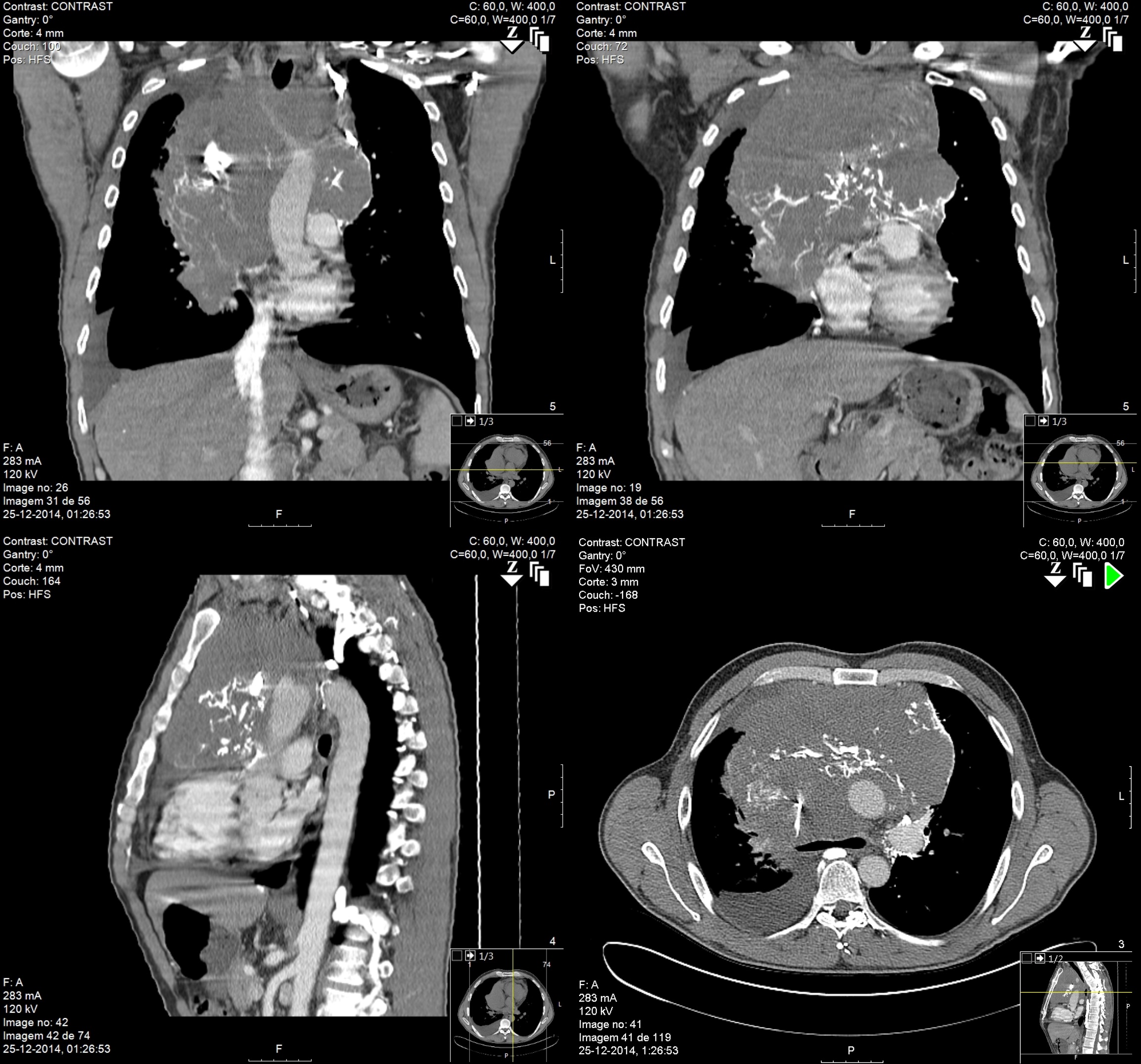

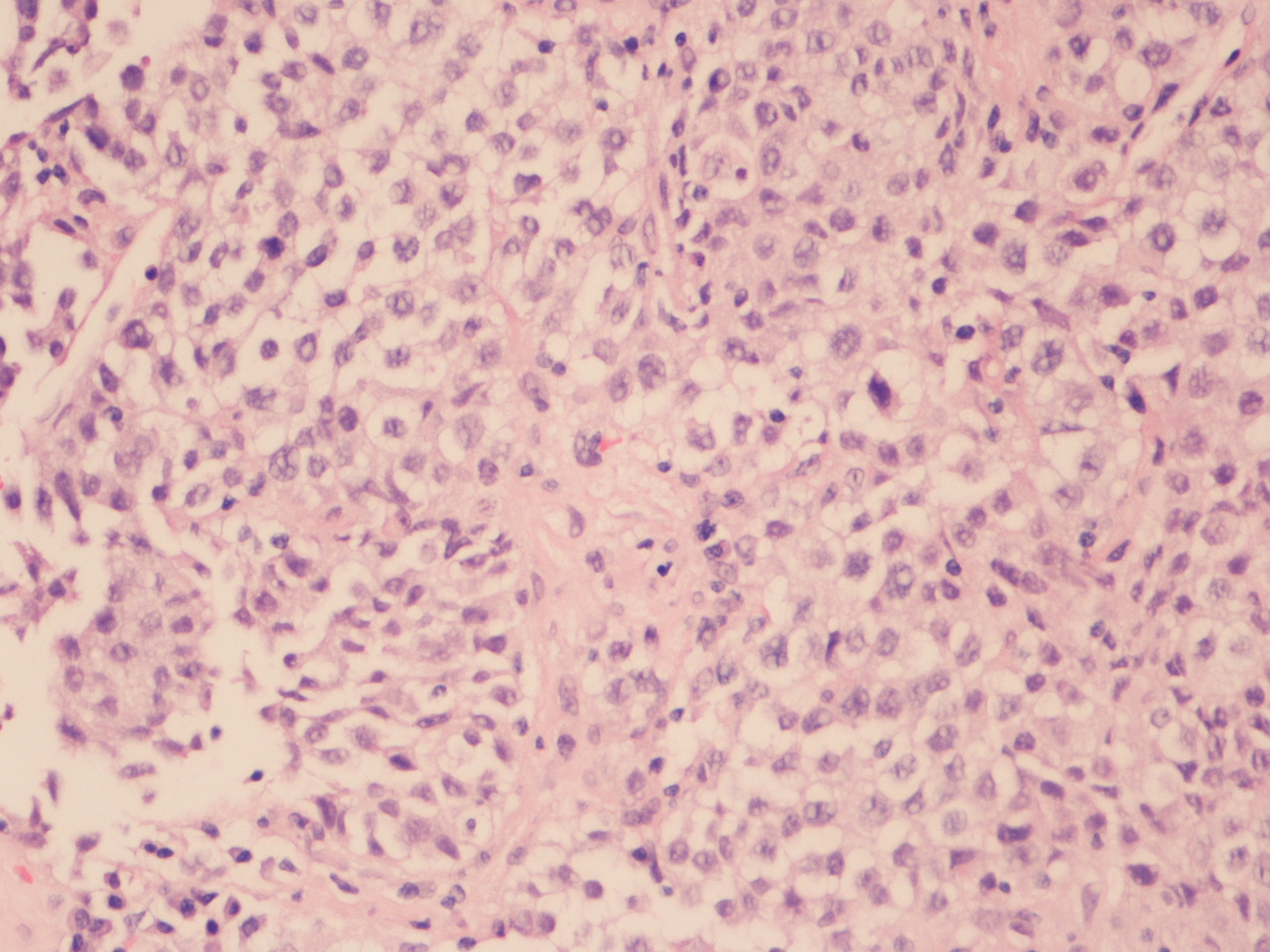

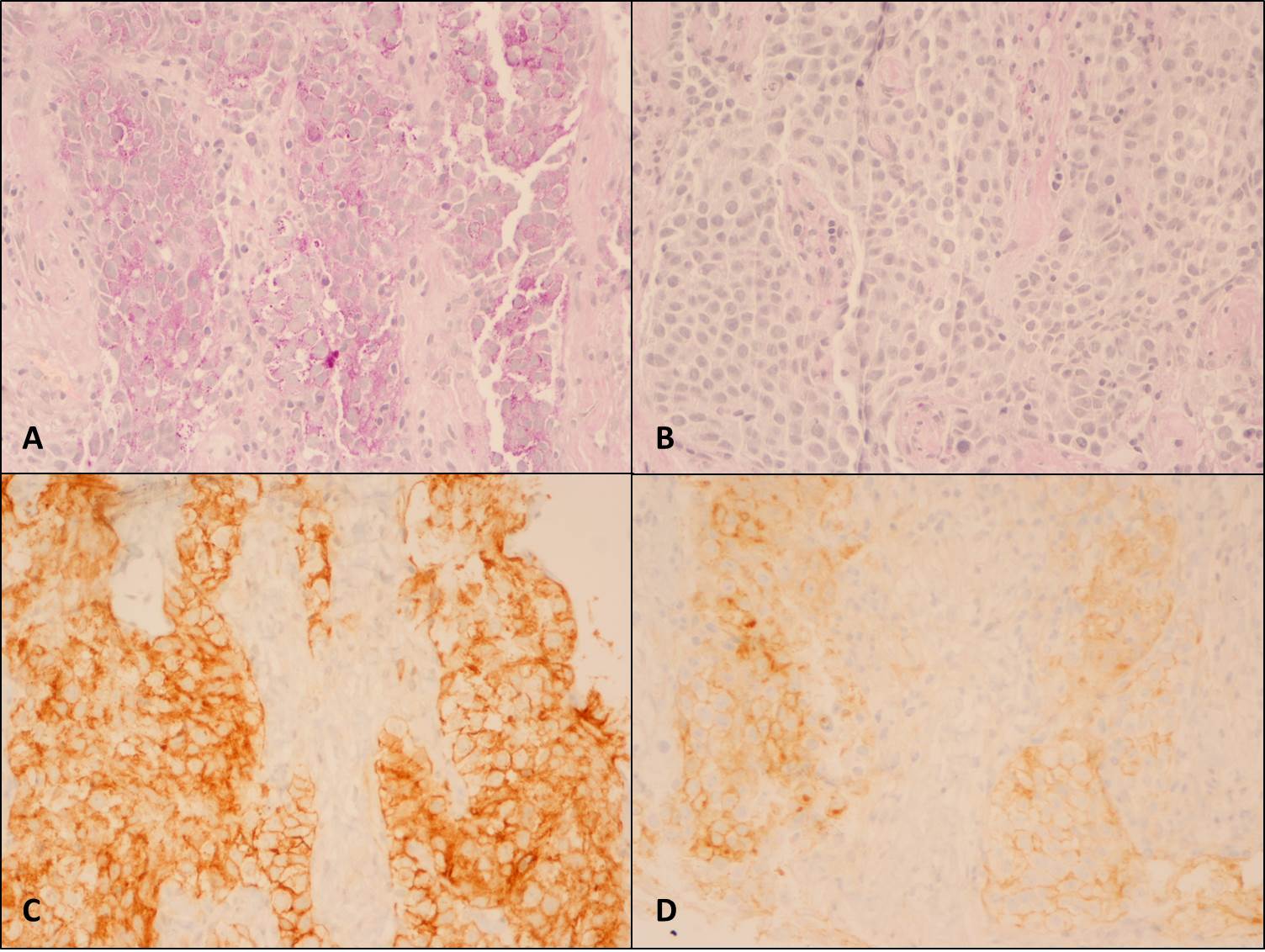

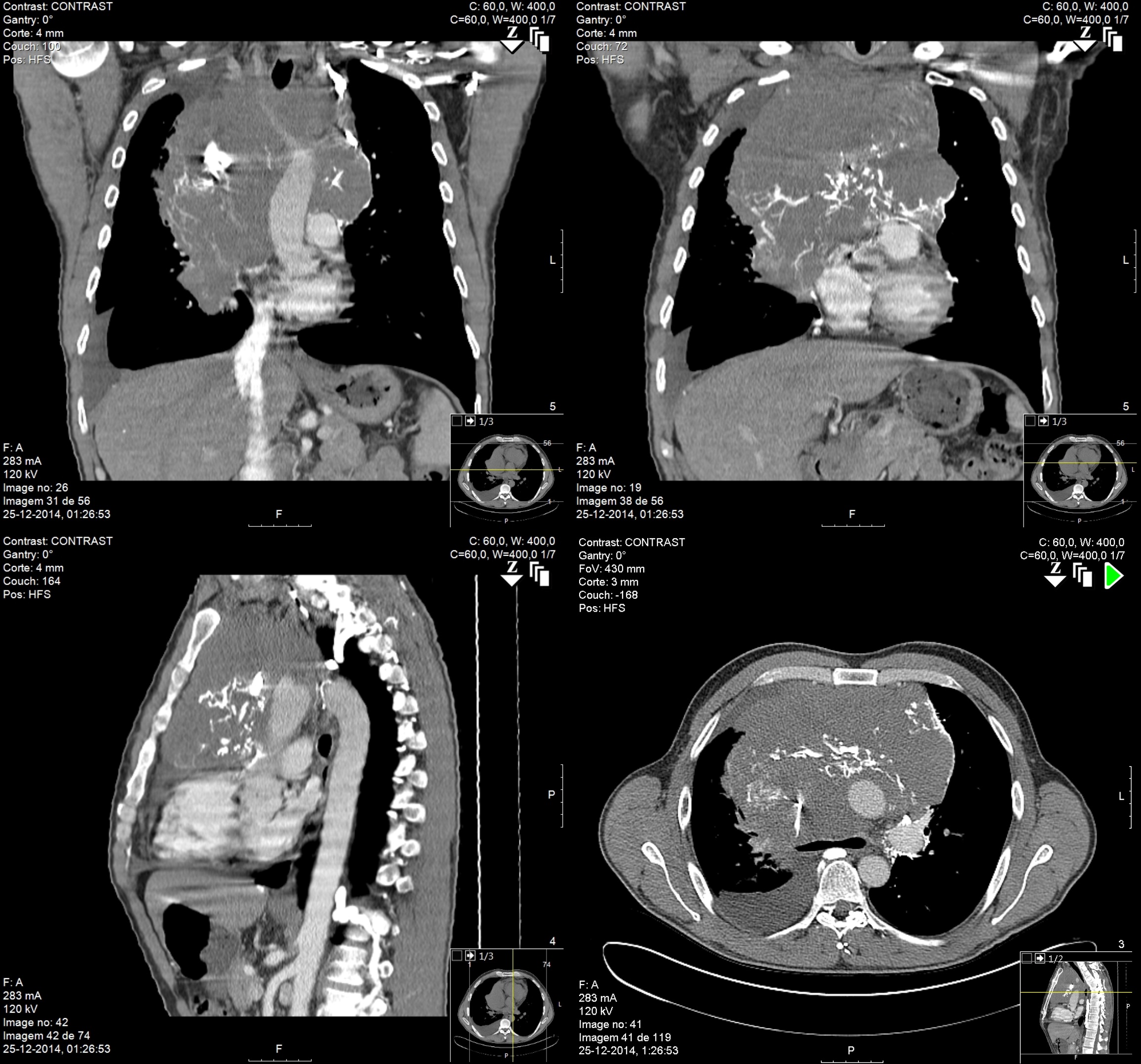

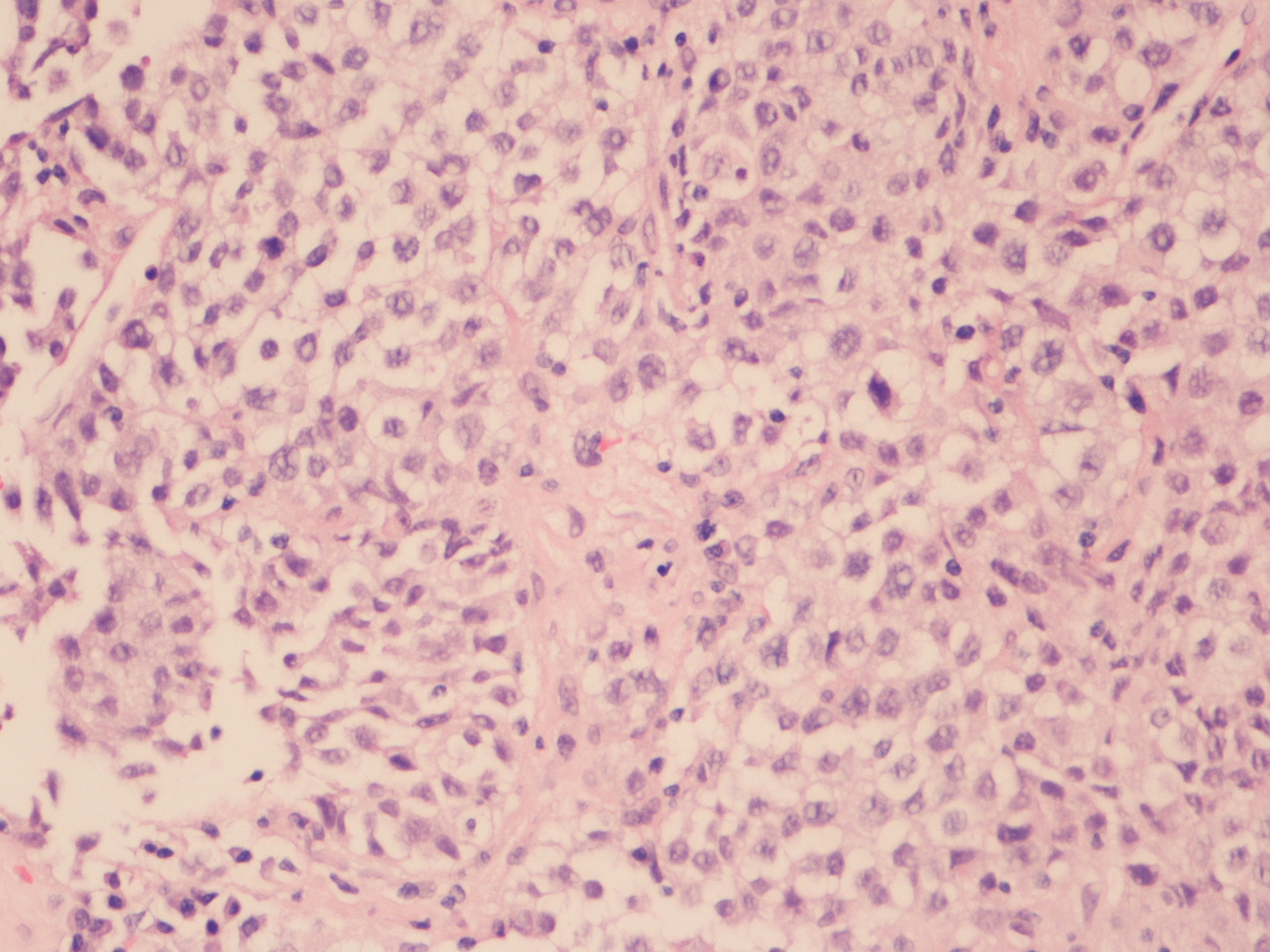

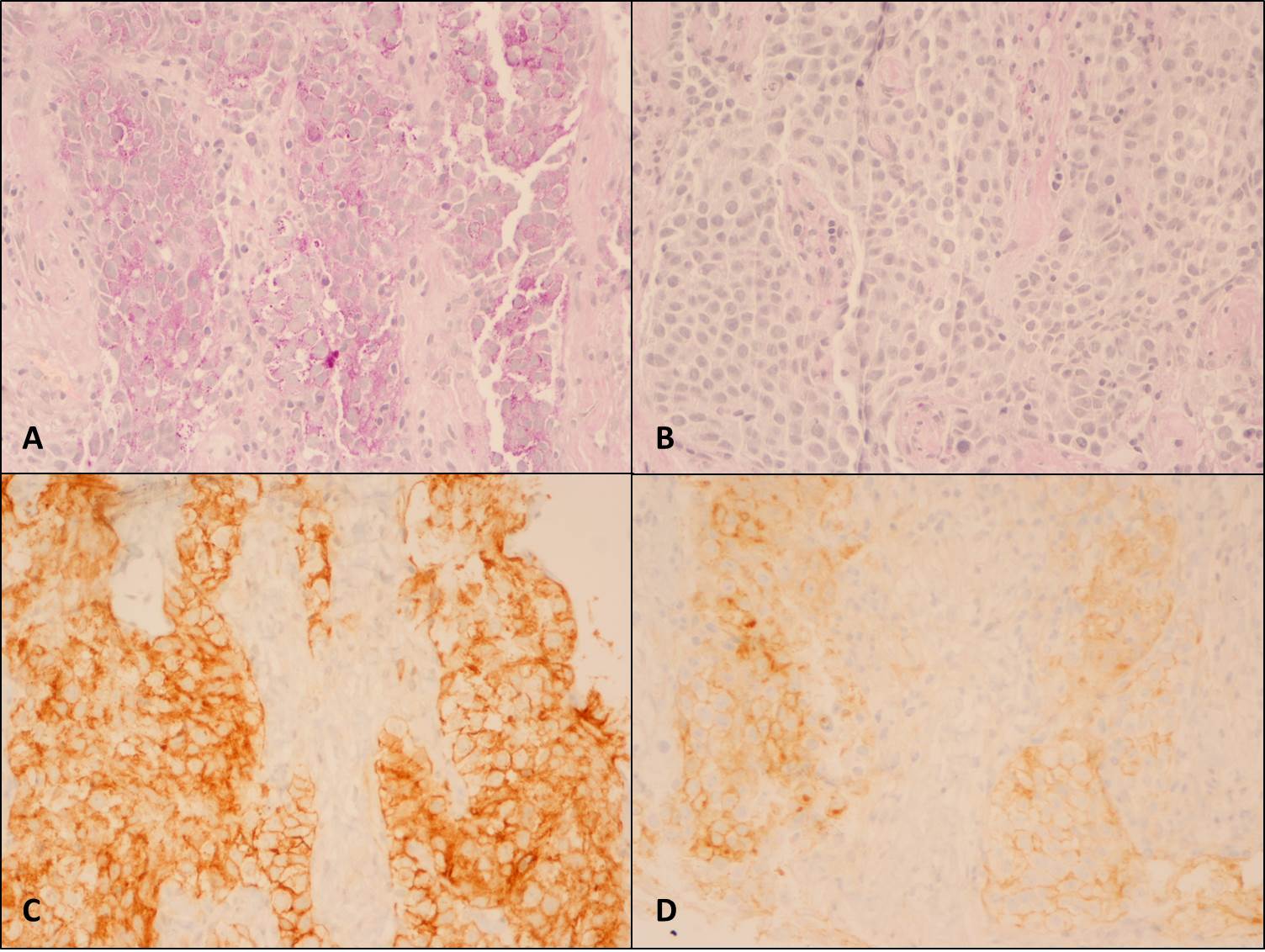

The chest X-ray (Figure 1) showed a bulky mediastinum mass and right pleural effusion. (Insert Figure 1 here) Chest-CT (Figure 2) further characterized this lesion as a solid mass of approximately 21 cm of larger diameter, profusely vascularized, with no calcic or lipidic components, located in the anterior and right paramedian mediastinum extending into the right thoracic operculum, incarcerating adjacent vascular structures – the right pulmonary artery, ascending aorta, aortic arch, supra-aortic vessels and proximal descending aorta. No contrast was seen in the superior vena cava suggesting thrombosis or tumor invasion. (Insert figure 2 here) A CT-guided core needle biopsy was performed, after which the patient initiated anticoagulation for SVCS with enoxaparin 1mg/Kg twice daily. The histologic findings (Figure 3) and the immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 4) established the diagnosis of seminoma. (Insert Figures 3 and 4 here)

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alkaline phosphatase and beta human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) were elevated, while alpha-fetoprotein level was normal (Table 1). Arterial blood gas analysis showed slight hypoxemia. Complete blood counts, renal, liver and thyroid function tests were normal. (Insert Table 1 here)

Clinical and ultrasonographic exams found no evidence of primary testicular tumor. Whole body CT revealed no signs of extramediastinal disease.

The patient was referred to an Oncology center and treated with four cycles of B.E.P. protocol (bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin). The chemotherapy was well tolerated and the outcome was successful with complete tumor remission. The anticoagulation started because of the SVCS was maintained during the treatment and for the first two years of follow-up during which the patient remained asymptomatic with no signs of disease persistence or relapse.

Discussion:Serologic features and histopathological findings of mediastinal seminoma parallel those of its gonadal equivalent.Unlike other germ cell tumors, seminomas have no reliable markers. They do not produce alpha-fetoprotein and β-hCG is only elevated in a minority of cases. However, as much as 50 percent of patients with extragonadal seminoma may have small to moderate increases in β-hCG. This elevation seems to reflect higher tumor burden

5, as seen in this case.LDH is a less specific and less sensitive tumor marker but it may be the only elevated marker in some seminomas and its serum level has prognostic value.

6The placental isoenzyme of alkaline phosphatase (PLAP) has been proposed as a plausible marker for seminomas. Evidence has been found indicating PLAP is significantly increased in seminoma tissue. Also, immunohistochemical studies demonstrated PLAP is found mainly on the seminoma cell membrane

(Figure 4 – D) supporting the finding that seminoma cells produce this isoenzyme, which may be released into the circulation.

7 The authors presume this justifies the overall alkaline phosphatase elevation seen in this case.

Due to the rarity of this tumor, treatment strategies rely largely on retrospective reviews and data inferred from collected evidence on treatment of advanced testicular seminoma.

Seminoma is a highly chemo and radiotherapy sensitive malignancy. However, in this particular location, primary irradiation has a higher disease recurrence rate and shorter overall survival.8-9Moreover, radiation therapy is associated with non-negligible toxicity such as increased frequency of late breast, lung, esophageal and other cancers, as well as coronary artery or valvular heart disease. Thus, cisplatin-based chemotherapy is the preferred treatment option and, for the majority of cases of mediastinal seminoma, a curative one.10-12

There is no consensus on the optimal management of postchemotherapy residual seminoma masses. Surgical resection is often technically difficult and may be unnecessary as most of them consist of necrosis, or a scirrhous or desmoplastic reaction.13Alternative approaches include imaging surveillance and biopsy of the mass. For greater than 3 cm seminoma remnants, FDG PET is a clinically useful predictor of viable tumor.14Salvage treatment should be reserved to histologically confirmed malignancy or evidence of progressive disease. Surgery is not usually recommended for the initial management of mediastinal seminomas because of the typical presence of bulky/metastatic disease.

SVCS results from any condition that leads to obstruction of the blood flow through the superior vena cava. In the presented case, external compression, possible tumor invasion and thrombosis coexist.

Formerly, malignancy related SVCS was considered an oncologic emergency. At present, it is recognized that it is often a prolonged process and that symptoms’ duration has no impact on treatment results, as long as the patient is clinically stable and the diagnostic workup is expeditious. Accordingly, in most cases, accurate diagnosis should precede emergent therapeutic intervention.15Tumor type primarily determines the prognosis of malignancy associated SVCS, so the main goals of management are to relieve symptoms and treat the underlying cancer.16

In patients with germ cell cancers and symptomatic SVCS, initial chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment.17When the SVCS results from intravascular thrombosis, systemic anticoagulation can be considered.

The presented case, illustrates the successful treatment of a bulky primary mediastinal seminoma as well as the resolution of the associated SVCS with cisplatin based chemotherapy.

Quadro I

Table 1 - Laboratory data

| Variable | Value | Reference |

| | | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13,5 | 13,5 – 18,0 |

| White-cell count (per mm3) | 4700 | 4400 – 11 300 |

| Platelet count (per mm3) | 205 000 | 150 000 – 350 000 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 37 | 17 - 43 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1,15 | 0,84 – 1,25 |

| AST (U/L) | 32 | <38 |

| CK (U/L) | 164 | <190 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 364 | 40 – 129 |

| Total Bilirrubin (mg/dL) | 0,72 | 0,3 – 1,2 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4,0 | 3,4 – 4,8 |

| LDH (U/L) | 379 | <248 |

| C- reactive protein (mg/L) | 43 | <6 |

| Beta-hCG (IU/L) | 94,72 | <0,8 |

| Alfa-fetoprotein (ng/mL) | 1,68 | 0,89 - 8,78 |

| TSH (mUI/mL) | 3,69 | 0.35 - 4.94 |

| FT4 (μg/dL) | 8,38 | 4,87 - 11,72 |

| Arterial Blood gases | | |

| pH | 7,38 | 7,35 – 7,45 |

| PaO2 mmHg | 63 | 75 – 100 |

| PaCO2 mmHg | 33 | 35 – 45 |

| FiO2 | 0,21 | 0,21 |

AST - Aspartate aminotransferase; Beta-hCG - Chorionic gonadotropin; CK - Creatine kinase; FT4 - Thyroxine, free; LDH - Lactate dehydrogenase; TSH – Thyrotropin.

Figura I

Chest radiograph shows mediastinal enlargement and right pleural effusion.

Figura II

Coronal, sagittal and transverse Chest CT images show a solid bulky mass, profusely vascularized, located in the anterior and right paramedian mediastinum, incarcerating adjacent vascular structures. No contrast is seen in the superior vena cava.

Figura III

Solid sheets or trabeculae of medium to large cell with abundant clarified cytoplasm, discretely irregular round nuclei with prominent nucleolus, set in a fibrous stroma with some lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Hematoxylin-eosin, X200).

Figura IV

Presence of glycogen in the cytoplasm, stained using Periodic acid Schiff (PAS) and unstained using PAS after digestion (PAS/D) with diastase enzyme (A – PAS, X200; B – PAS/D, X200). [C ] Universal positivity with anti-CD117 antibody, typically cytoplasmic staining with stronger accentuation along the cell membranes (CD117, X200). [D] Weak but diffuse positivity with anti-Placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP) antibody, characteristically staining cell membrane (PLAP, X200).

BIBLIOGRAFIA

References

1- Juanpere S, Cañete N, Ortuño P, Martínez S, Sanchez G, Bernado L. A diagnostic approach to the mediastinal masses. Insights Imaging. 2013; 4:29-52.

2- Strollo D, Christenson R, Jett J. Primary mediastinal tumors. Part 1: tumors of the anterior mediastinum. Chest. 1997; 112:511-22.

3- Duwe B, Sterman D, Musani A. Tumors of the mediastinum. Chest. 2005; 128:2893–2909.

4- Khan FY, Al Ani A, Allaithy MS, Al-Bozom IA. A young male with shortness of breath. Ann Thorac Med. 2008; 3(1): 28-30.

5- Bokemeyer C, Nichols CR, Droz JP, Schmoll HJ, Horwich A, Gerl A, et al. Extragonadal germ cell tumors of the mediastinum and retroperitoneum: results from an international analysis. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2002; 20(7):1864-73.

6- Mencel PJ, Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, Vlamis V, Bajorin DF, Bosl GJ. Advanced seminoma: treatment results, survival, and prognostic factors in 142 patients. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12(1):120.

7- Koshida K, Nishino A, Yamamoto H, Uchibayashi T, Naito K, Hisazumi H, et al. The role of alkaline phosphatase isoenzymes as tumor markers for testicular germ cell tumors. The Journal of Urology. 1991; 146(1):57-60.

8- Bokemeyer C, Droz JP, Horwich A, Gerl A, Fossa SD, Beyer J, et al. Extragonadal seminoma: an international multicenter analysis of prognostic factors and long term treatment outcomes. Cancer. 2001; 91(7):1394-401.

9- Fizazi K, Culine S, Droz JP, Terrier-Lacombe MJ, Théodore C, Wibault P, et al. Initial management of primary mediastinal seminoma: radiotherapy or cisplatin-based chemotherapy? Eur J Cancer. 1998; 34(3):347-52.

10- Rodney AJ, Tannir NM, Siefker-Radtke AO, Liu P, Walsh GL, Millikan RE, et al. Survival outcomes for men with mediastinal germ-cell tumors: the university of texas M. D. Anderson cancer center experience. Urol Oncol. 2012; 30(6):879-85.

11- Gholam D, Fizazi K, Terrier-Lacombe MJ, Jan P, Culine S, Theodore C. Advanced seminoma-treatment results and prognostic factors for survival after first-line, cisplatin-based chemotherapy and for patients with recurrent disease. Cancer. 2003; 98(4):745-52.

12- Macchiarini P, Ostertag H. Uncommon primary mediastinal tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2004; 5(2):107-18.

13- Bokemeyer C, Hartmann JT, Fossa SD, Droz JP, Schmol HJ, Horwich A, et al. Extragonadal germ cell tumors: relation to testicular neoplasia and management options. APMIS. 2003; 111(1):49-59.

14- De Santis M, Bokemeyer C, Becherer A, Stoiber F, Oechsle K, Kletter K, et al. Predictive impact of 2-18fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography for residual postchemotherapy masses in patients with bulky seminoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001; 19(17):3740-4.

15- Lepper PM, Ott SR, Hoppe H, Schumann C, Stammberger U, Bugalho A, et al. Superior vena cava syndrome in thoracic malignancies. Respir Care. 2011; 56(5):653-66.

16- Wilson LD, Detterbeck FC, Yahalom J. Clinical practice. Superior vena cava syndrome with malignant causes. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356(18):1862-9.

17- Straka C, Ying J, Kong FM, Willey CD, Kaminski J, Kim DW. Review of evolving etiologies, implications and treatment strategies for the superior vena cava syndrome. Springerplus. 2016; 5:229.