Introduction

Caroli’s disease and Caroli’s syndrome are rare congenital disorders, in most cases transmitted in an autosomal recessive form.1,2 The estimated incidence is extremely low (1:1.000.000) with no specific signs or symptoms.3 Caroli’s disease is characterized by non-obstructive, multifocal, segmental dilatation of large intrahepatic bile ducts. Caroli’s syndrome has the involvement of all levels of the biliary tract with the presence of congenital fibrosis and may be accompanied by cholangiocarcinoma, calculi of the intrahepatic duct, cholangitis, pancreatic cyst and renal cystic disease or medullary sponge kidney.1,3,4 Although the anatomical changes are present since birth, the majority of the cases are diagnosed during adulthood.1

The disease usually runs a long-lasting course with recurrent episodes of cholangitis, which may be complicated by intrahepatic calculi and HA formation with high risk of bacteremia and sepsis.1,3

The diagnosis is made histologically or by imaging studies demonstrating the continuity of the cystic liver lesions within the biliary tree.4

Clinical Report

In July 2016, a 58-year-old female was admitted to our hospital´s Emergency Unit (ER) with symptoms of malaise, sweating and prostration with two days of evolution, nausea and vomiting of food content associated with two episodes of watery diarrhea, with no pus, mucus or blood. No fever or anorexia. Her prior medical history included a hypertensive cardiopathy, insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus, cholecystectomy, and Caroli’s disease, diagnosed at the age of 33.

She had a history of two hospitalizations 3 years ago with diagnosis of cholangitis and HA with positive cultures for Entamoeba histolytica (Figure 1).

A 2014 magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showed a dysmorphic liver, with atrophy of the left lobe and posterior segments of the right lobe with dilatation of segmental intrahepatic bile ducts and increased caliber of the proximal common bile duct but without evidence of fibrosis. (Figure 2)

At our hospital´s ER, the physical examination showed diffuse abdominal pain and fever (tympanic temperature 38ºC). Laboratory tests showed leukocytosis, elevated blood glucose, C-Reactive Protein, transaminases, gamma glutamyl transpeptidase, serum alkaline phosphatase and hyperbilirubinemia (Table 1). The presence of abdominal pain led us to perform an abdominal US scan, which showed aerobilia on the left flank and hepatomegaly, undervalued by the frequent presence in previous studies.

The diagnosis of acute decompensated diabetes was assumed and the patient was admitted to our ward, after performing urine and blood cultures. During hospitalization there was progressive clinical deterioration and elevation of inflammatory parameters. Despite institution of empirical antibiotic therapy with Ceftriaxone, the patient develops severe type 1 respiratory failure, requiring oxygen therapy with Venturi mask at a FiO2 of 60%. Initial investigation for pulmonary thromboembolism with chest CT angiography showed no evidence of thrombotic disease, but disclosed an image suggestive of an HA with 5 centimeters diameter.Escherichia coli (multisensitive) was isolated in urine culture and Enterobacter asburiae, Enterococcus faecalis and Raoultella ornithinolytica were found in blood cultures. Antibiotic therapy was escalated to pathogen directed therapy with ertapenem and ampicillin. Ketoacidosis was controlled with insulin perfusion and later with long-acting insulin. It was also assumed acute decompensated heart failure with fluid overload, which responded favorably to diuretic therapy, with progressive improvement of respiratory function. Infectious endocarditis associated with bacteremia was excluded by transthoracic echocardiography with no evidence of valvular vegetations and with good left ventricular systolic function.

For clarification of possible intraabdominal infectious origin with which to explain bacteremia we repeated abdominal and pelvic CT which showed a dismorfic liver with hypertrophy of segment IV, atrophy of segments II and III of the right lobe, dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts of the left lobe with a confluent and voluminous hypodense lesion consistent with cholangitis complicated with a HA. (Figure 3)

She underwent US guided percutaneous transhepatic abscess drainage which remained in passive drainage for 15 days, initially with pus drainage followed by hemato-serous content. Abscess pus culture revealed the presence of Escherichia coli sensitive to ampicillin and co-trimoxazole.

During hospitalization, the patient underwent 21 days of intravenous directed antibiotic therapy, with a good clinical response and normalization of inflamatory and hepatic laboratory parameters.

The patient was discharged with indication to maintain antibiotic therapy for 3 weeks and to be reviewed in hepatology consult. The control Abdominal CT and the MRCP, performed seven weeks and two months later respectively, showed no signs of abscess in the liver parenchyma.

Discussion

In our case the patient has the diagnosis of Caroli’s disease demonstrated by a MRCP with the presence of dysmorphic liver, with atrophy of the left lobe and posterior segments of the right lobe, where was observed dilatation of segmental intrahepatic bile ducts and increase caliber of the proximal common bile duct without evidence of fibrosis. We could not find a biopsy result in our patient clinical history. Caroli’s syndrome diagnosis was excluded because hepatic fibrosis and kidney disease were absent. Although a genetic study was not performed, we assumed that our patient did not have an autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease because kidneys were not affected.

The anatomical changes of Caroli’s disease predisposes intrahepatic ductal ectasia and the stagnation of the bile which favors infections. The Charcot´s triad could not be present and symptoms may be unspecific with intermittent abdominal pain and/or fever without jaundice. The differential diagnosis includes primary sclerosing cholangitis, recurrent pyogenic cholangitis, polycystic liver disease, choledochal cysts, biliary papillomatosis, liver abscess and sepsis.4,5Laboratory studies typically shows an elevation of ALP and GGT, direct bilirubin and leukocytosis with a predominance of neutrophils. Liver enzymology is well preserved initially, but may be affected by progressive liver damage due to biliary obstruction and recurrent cholangitis.1,4 In our case, laboratory stands out a slightly elevation of AST and ALT, elevated GGT, ALP and direct bilirubin. Furthermore, the patient had elevated inflammatory parameters, namely, CRP 37.6 mg/dL and leukocytosis of 12280 x109/L with 87.8% neutrophils.

Around 80 to 100% of patients with cholangitis have positive bile’s cultures and 20-80% have bacteremia, being the principal microorganism found in the cultures Escherichia coli.6 The biliary tree is the most common route of infection for HA formations, responsible for 30%–50% of cases. HA can be difficult to diagnose. The symptomatology is variable, objective and laboratory findings are relatively nonspecific. The most common abnormalities are elevated white blood cell count, elevated CRP, hypoalbuminemia, elevated AST, ALT, ALP, GGT, bilirubin, and international normalized ratio (INR). Diagnosis is made by imaging in 90% of cases. However, 25% of patients had equivocal results in the emergency department, and 14% had a false negative result on US.7,8 In our case we performed an abdominal US scan in the emergency department which did not show relevant pathological changes. The patient presented leukocytosis with elevated CRP. However, in this specific case, elevated AST, ALT, ALP, GGT and bilirubin could also be explained by the underlying condition of Caroli’s disease.

Considering the differential diagnosis list, symptoms, signs, laboratory and imaging findings (US and CT) and the fact that our patient is cholecystectomized the most likely diagnosis in our case is Caroli’s disease complicated with cholangitis and HA.

Bacterial cholangitis is the most frequent presentation and life-threatening complication of Caroli’s disease, and usually has a recurrent course. The prognosis is variable depending upon the severity of disease and the presence of coexisting renal dysfunction. Recurrent infections can be associated with significant morbidity.1,3,5 In our case the patient has a preserved renal function and a renal image with no pathological findings. The last hospitalization for complications of Caroli’s disease was 3 years before this admission.

The medical treatment is often not satisfactory despite the different antibiotic associations, and the presence of HA is usually followed by a progressive loss of quality of life and death due to uncontrolled sepsis. Repeated palliative treatments, with antibiotic therapy and drainage procedures, could result in persistence of the symptoms and increase the risk of malignant transformation.2,4,5,9

The treatment of patients with Caroli’s disease depends on the clinical features of the disease and the location of biliary abnormalities. Surgery can offer a definite therapy in localized Caroli’s disease. When there is a diffuse involvement with hepatic fibrosis, liver transplantation represents the only curative treatment for the symptomatic Caroli’s disease but a majority dies within 5-10 years when cholangitis occurs. The poor prognosis and the sizable morbidity and mortality rates after liver transplantation still suggest that the timely recognition of indications for surgical treatment is of major importance.3,5 Because of liver diffuse involvement and poor characterization of Caroli’s disease diagnosis, our patient was hospital discharged with indications to maintain surveillance in hepatology consultation for early diagnosis of disease complications and evaluation of therapeutic options, including medical indication for a more invasive treatment.

Conclusion

Although Caroli´s disease is a rare disease with nonspecific signs and symptoms, it is important to remember the existence of this pathology in order to make a diagnostic march that allows a correct characterization of the disease.

It is important to be alert to possible complications of this pathology, difficult to diagnose due to the non-specificity of the findings. Bacterial cholangitis is the most frequent presentation and life-threatening complication of Caroli’s disease, and usually has a recurrent course, which can be associated with significant morbidity. The biliary tree is the most common route of infection for HA formations. Although diagnosis is made by imaging, there is a significant percentage of false negative result on emergency department US scans.

The treatment of patients with Caroli’s disease depends on the clinical features of the disease so these patients should be referred to a specialized consultation in order to evaluate possible curative treatments.

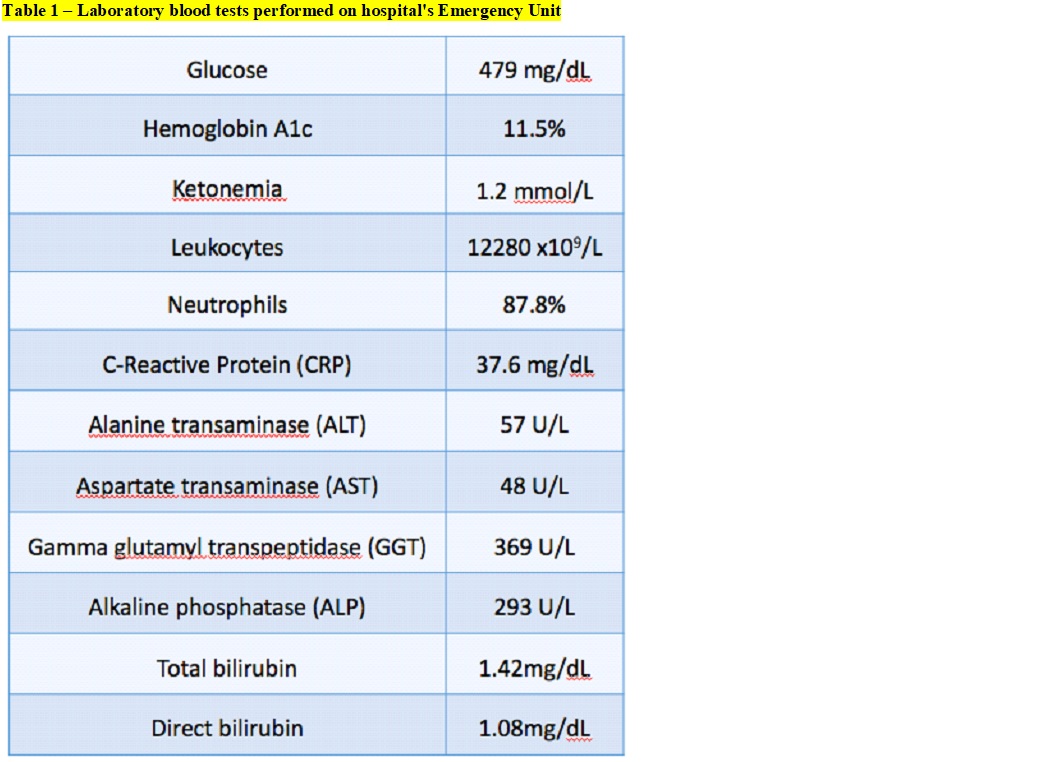

Figura I

Laboratory blood tests performed on hospital´s Emergency Unit

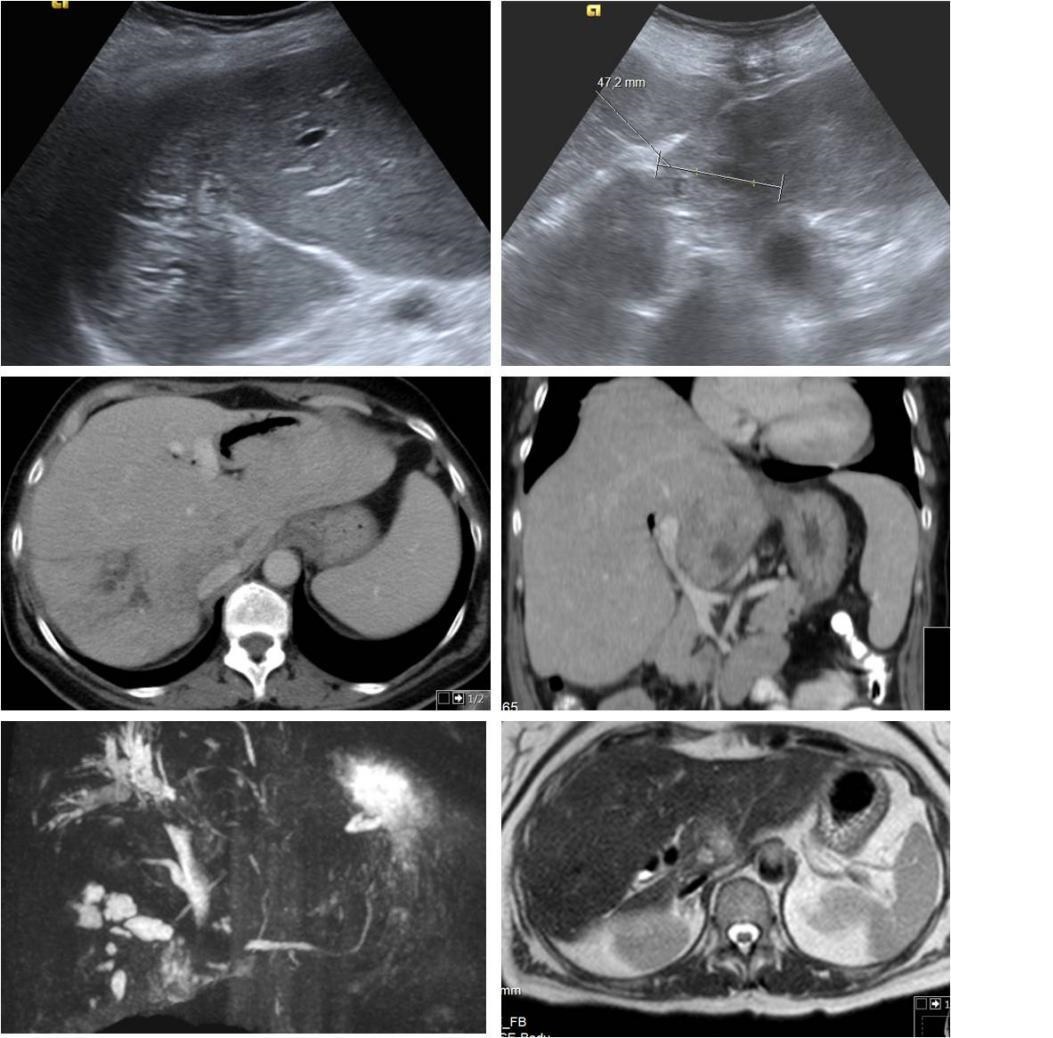

Figura II

Images of 2013 hospital admission-Abdominal US with area of hyperechogenicity and echoestructural heterogeneity with tubular images suggestive of intrahepatic biliary ectasia. Inferior slope of the left lobe with hypoechoic nodular image with about 22mm. Possible Caroli disease with infectious complication. MRCP with image of a poorly defined nodular zone 2 x 2 cm, hypointense in T1 and discretely hyperintense in T2 in posterior location of the left hepatic lobe. Dysmorphic liver, with atrophy of the left lobe and the posterior segments of the right lobe that have greater heterogeneity of signal and segmental dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts with aerobilia and some not pure content in the interior.

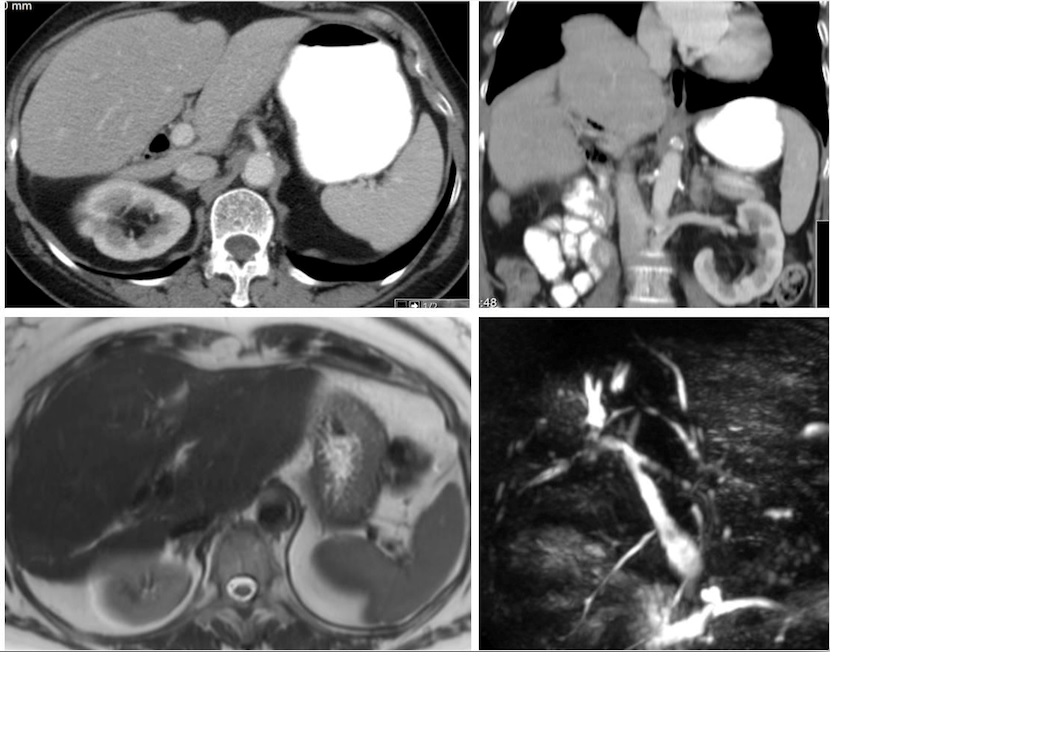

Figura III

Images of 2014 follow-up -Abdominal CT with decreased dimensions of hepatic segments VII and VIII, with compensatory hypertrophy of the rest, with dilatation of the biliary tract, with aerobilia mainly of the left lobe. No space occupying lesions. MRCP showed a dysmorphic liver, with atrophy of the left lobe and posterior segments of the right lobe with dilatation of segmental intrahepatic bile ducts and increased caliber of the proximal common bile duct but without evidence of fibrosis

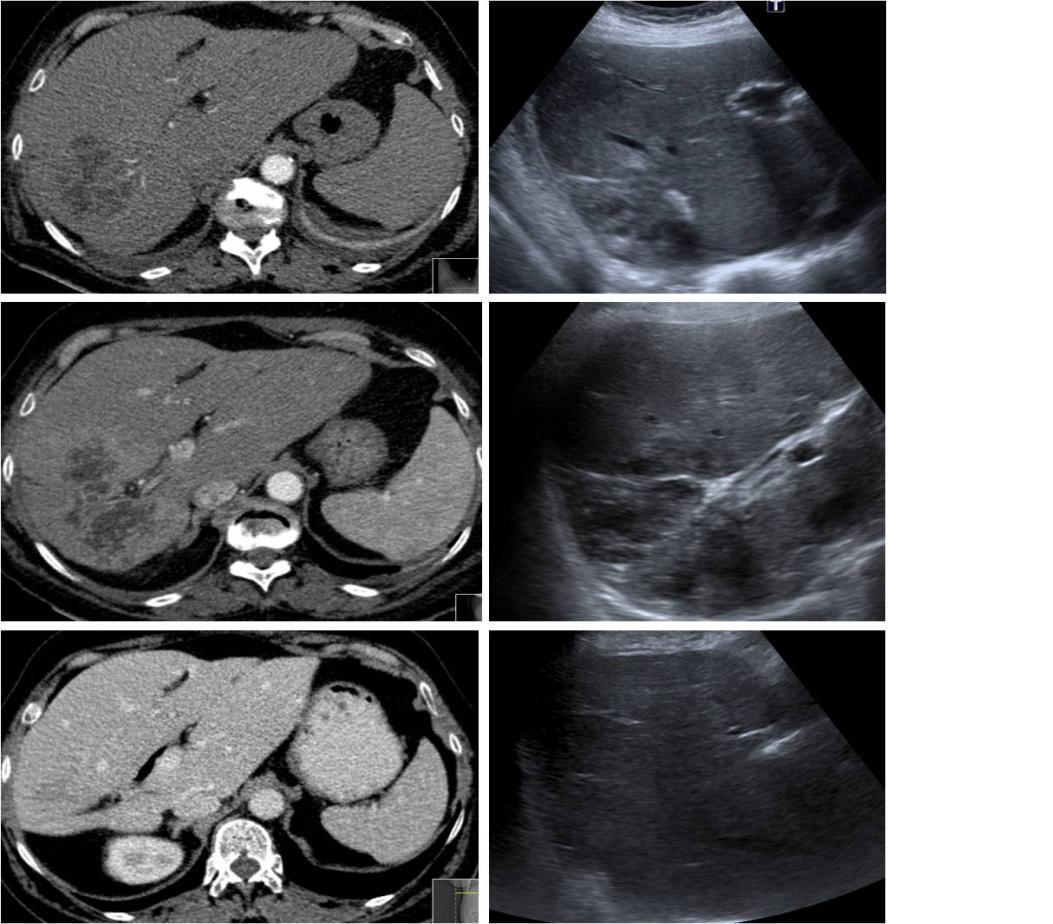

Figura IV

Images of 2016 hospital admission -Abdominal CT with presence of large focal alteration with confluent hypodense areas with peripheral contrast uptake, aspects interpreted as a cholangitis process complicated with hepatic abscess. The abscess has a larger axis of about 9.2cm. Abdominal US showed an heterogeneous area in the posteromedian region of the right hepatic lobe with about 8.5 cm of largest sonographic axis.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

.

References

1- Caroli disease, http://www.uptodate.com/contents/caroli-disease; (online, 14 September 2016)

2- M. Zahmatkeshan, A. Bahador, B. Geramizade, V. Emadmarvasti, S. A. Malekhosseini. Liver Transplantation for Caroli Disease. Int J Organ Transplant Med. 2012; 3(4): 189–191.

3- Z. Wang , Y. Li , R. Wang, Y. Li, Z. Li, L. Wang, et all. Clinical classification of Caroli´s disease: an analysis of 30 patients. HPB (Oxford). 2015 Mar;17(3):278-283.

4- O. Yonem, Y. Bayraktar. Clinical characteristics of Caroli’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007 Apr 7; 13(13): 1930–1933.

5- J. Lendoire, P. Schelotto, J. Rodríguez, F. Duek, C. Quarin, V. Garay, et al. Bile duct cyst type V (Caroli´s disease): surgical strategy and results. HPB (Oxford). 2007; 9(4): 281–284.

6- B. Almirante, C. Pigrau. Acute cholangitis. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin.Septiembre 2010;28(Suppl 2):18-24

7- Y. Sato, X. S. Ren, Y. Nakanuma. Caroli´s Disease: Current Knowledge of Its Biliary Pathogenesis Obtained from an Orthologous Rat Model. Int J Hepatol. 2012: 107945.

8- J. Rahimian, T. Wilson, V. Oram, R. S. Holzman. Pyogenic Liver Abscess: Recent Trends in Etiology and Mortality. Clin Infect Dis. (2004) 39 (11): 1654-1659.

9- H. Flisfisch, A. Heredia. Colangitis aguda: revisión de aspectos fundamentales. Rev. Medicina y Humanidades. 2011, Vol. III Nº 1-2: 39-44