Introduction

Systemic Mastocytosis (SM) is a clonal disorder of hematopoietic stem cell characterized by pathologic proliferation of mast cell (MC) in one or more organ system. It is a rare disease and the exact incidence is unknown, but the epidemiologic study, conducted in Europe and in the United States, revealed a prevalence of 1/60.0001. In the 2016 World Health Organization classification, mastocytosis is considered as a separate entity and includes Cutaneous mastocytosis, indolent SM, smoldering SM, SM with an associated hematologic neoplasm, aggressive SM, mast cell leukemia, and mast cell sarcoma2. A myriad of clinical symptoms occur as a consequence of increased MC proliferation in organs and tissues and MC mediator release. The clinical presentation and the course are variable, ranging from skin-limited involvement to different systemic forms. Bone manifestations are one of the most frequent symptoms of SM, particularly in adults3 and may represent the only manifestation of the disease.

Clinical case

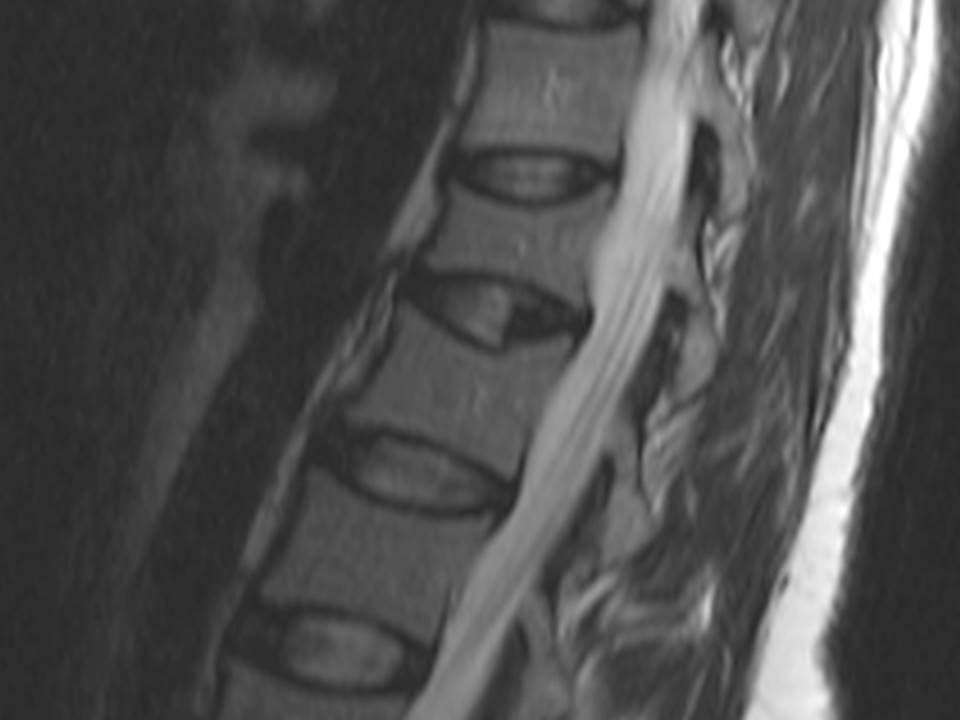

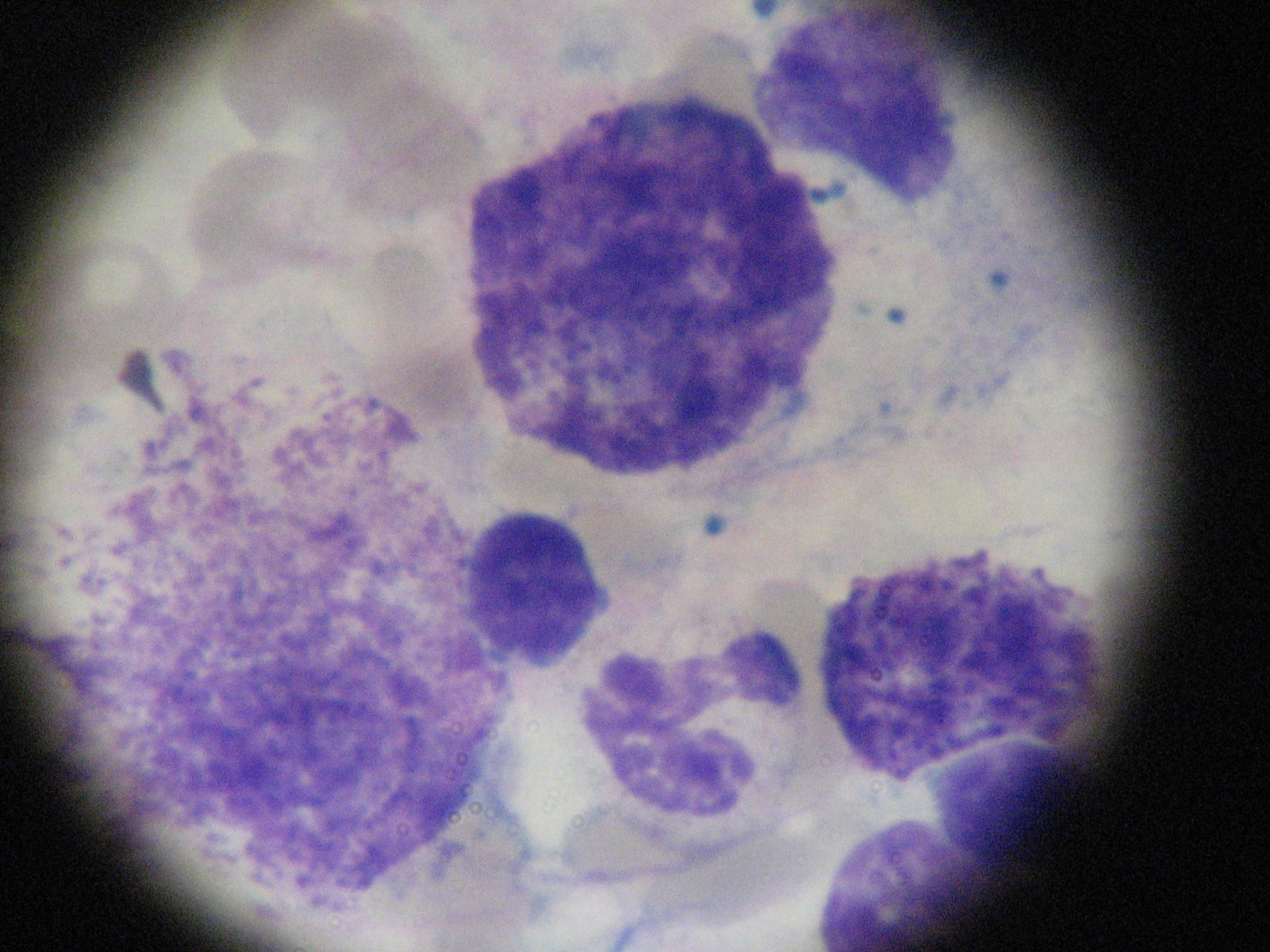

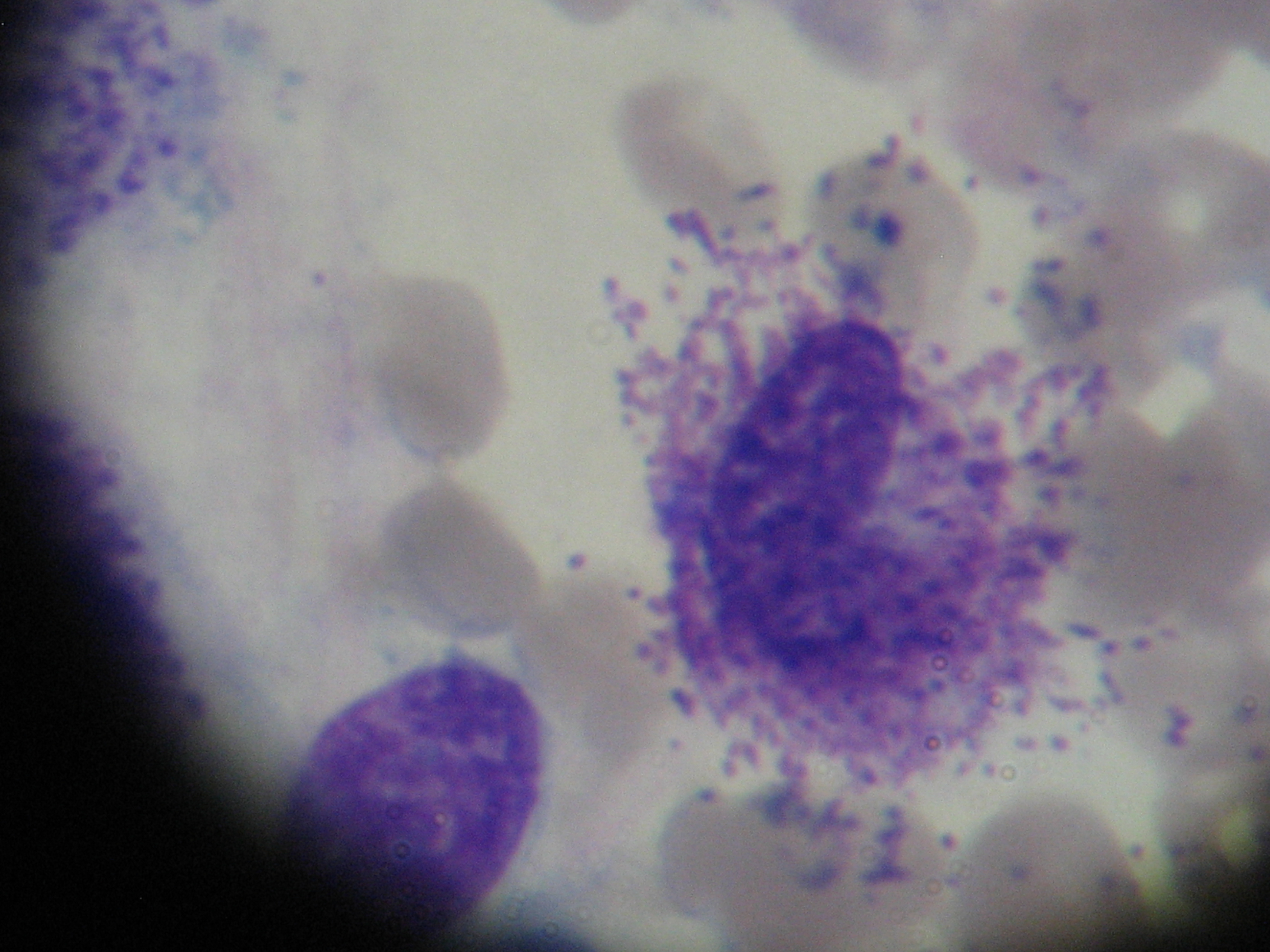

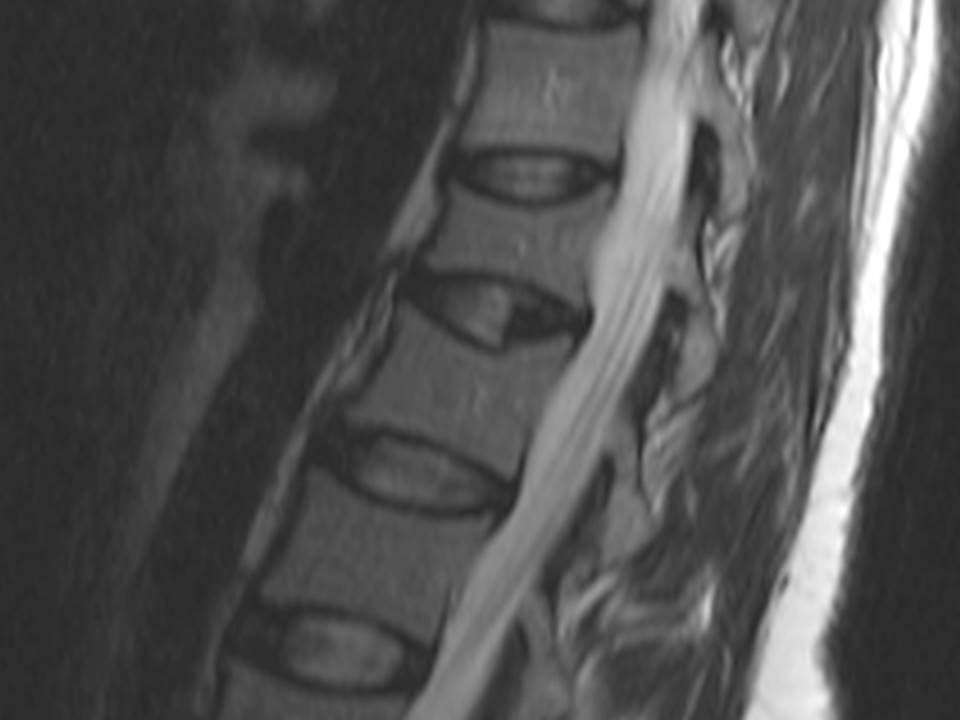

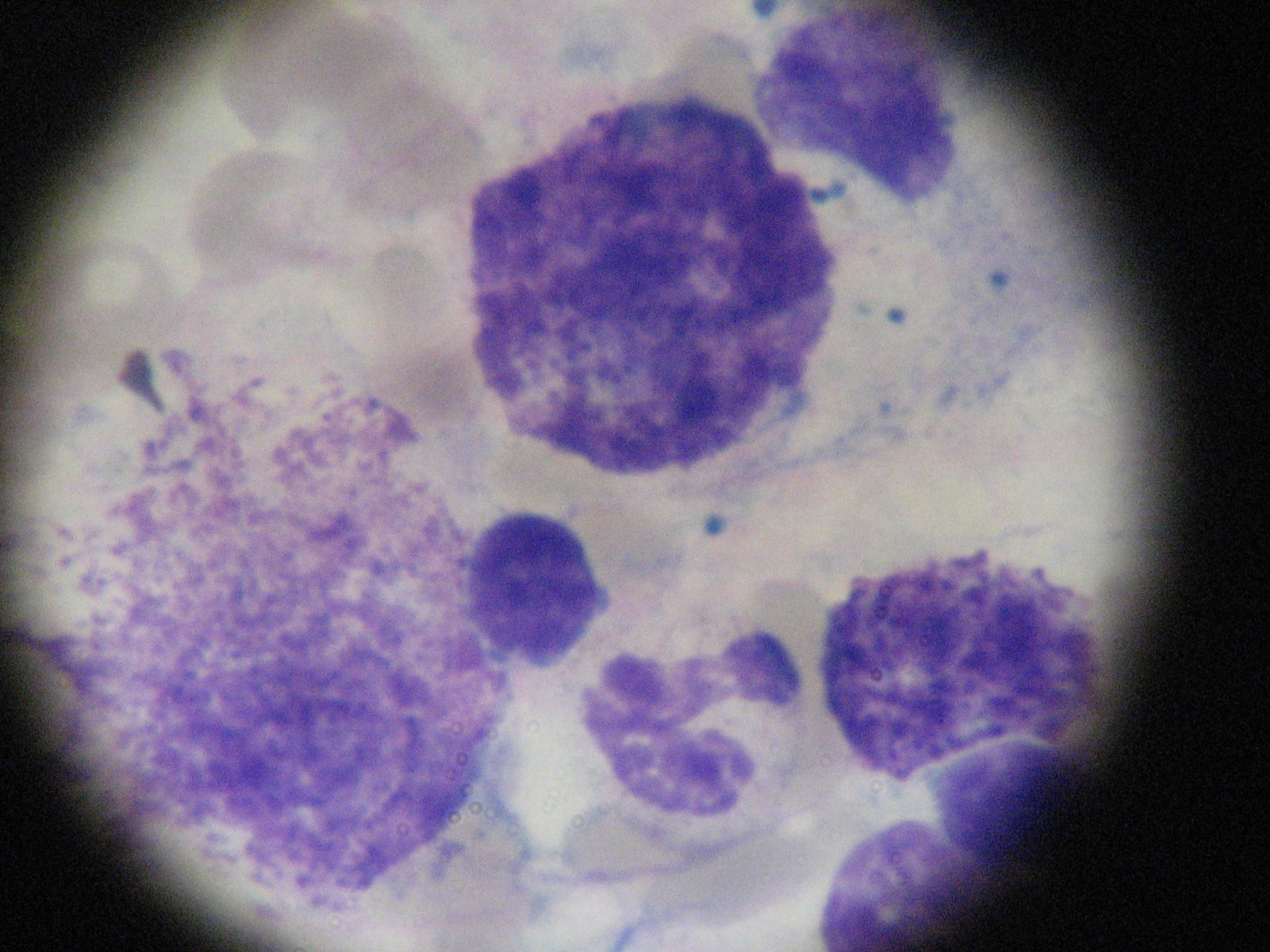

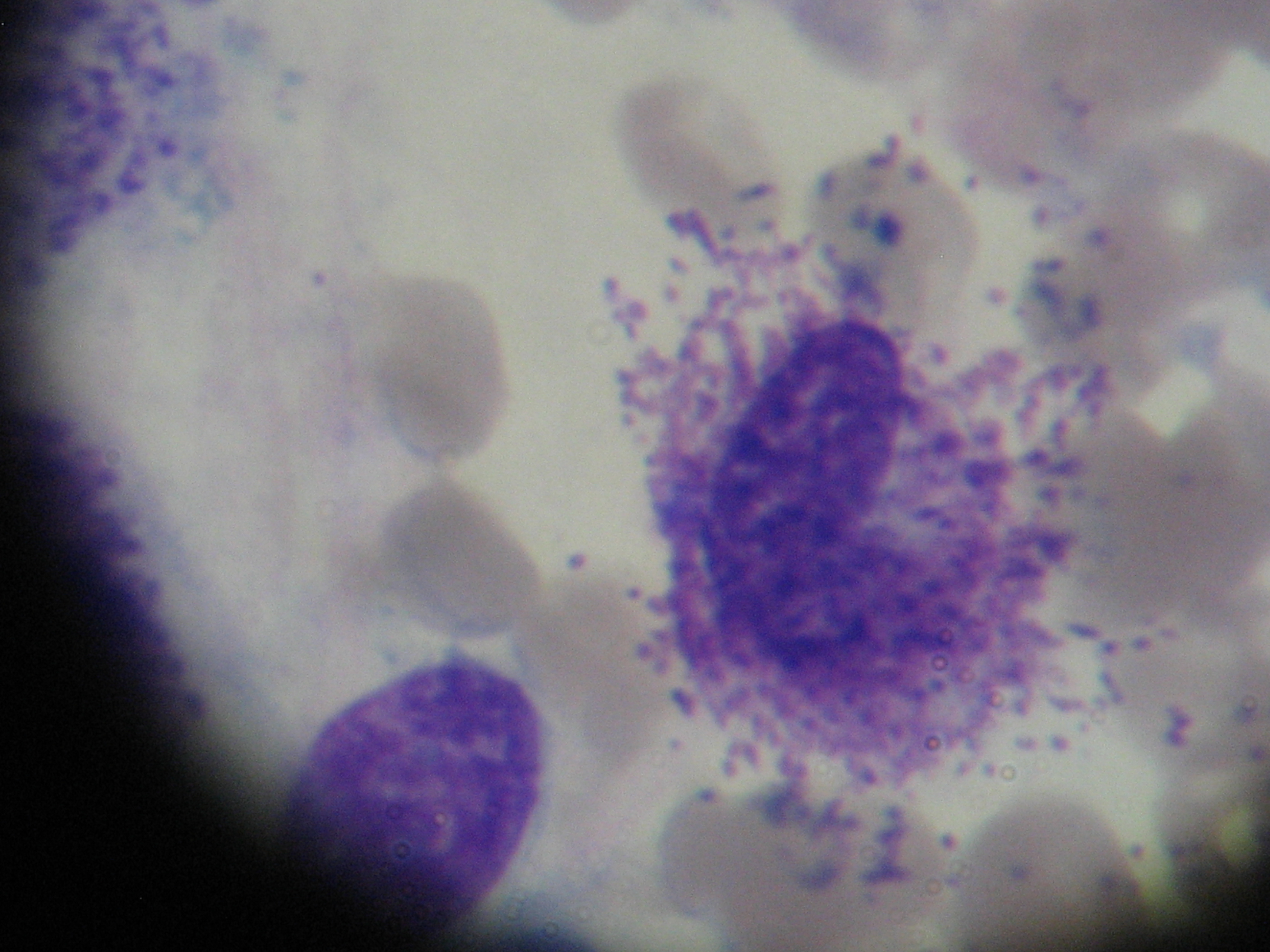

A 37-year-old caucasian female was referred to our department with refractory osteoporosis. Her significant past medical history included a previous episodes of low back pain with no trauma and a low-trauma Colles fracture in 2010. Imaging assessment performed in 2010 included a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) showing a T-score of -4.1 in the spine and of -2.5 in the femoral neck areas; a magnetic resonance imaging of the dorso-lumbar spine revealing fracture of L1 vertebra and biconvex aspect of L2 vertebra (Figure 1). She was medicated with zolendronic acid during four years, and then with strontium ranelate. Serial DXA measurements performed in 2014 revealed T-score of -4.1 in the spine and of -2.3 in the femoral neck areas. Our patient denied any comorbidity, use of tobacco, alcohol or any medications and illicit drugs. She also had no history of drug allergies and there was no known family history. The patient did not report any constitutional symptoms like weight loss, fever, fatigue, malaise, night sweating or decreased appetite. Her physical examination was unremarkable. The need to exclude secondary causes of osteoporosis led to a broad laboratory assessment which was normal and included complete blood count, C-reactive protein and sedimentation rate; kidney, liver and thyroid function; phosphorus-calcium metabolism with calcium, phosphorus, 25-hydroxyvitamin D and parathyroid hormone; iron study, homocysteine and celiac disease antibody and also hormonal study including testosterone level, cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone. Further testing revealed a high serum tryptase level of 22.2μg/L (reference range <11.4) and this guided us to the next step- bone marrow study. The diagnosis of mastocytosis was confirmed by the presence of dense agregates of MC on the bone marrow aspirate (Figure 2 and 3) and MC expressing aberrant CD2 and CD25 on the immunophenotype of bone marrow aspirate. It was not detected KIT D816V mutation. The patient was referred to the department of Hematology and she is currently medicated with calcium and Vitamin D supplements, zolendronate (four mg once every four weeks) and Interferon Alfa (IFN-Alfa) (three million units three times weekly). A new DXA performed in 2018 showed T-score of -3.1 in the spine and of -2.1 in the femoral neck areas.

Discussion

Mastocytosis is an unusual disease associated with pathologic proliferation of MC and their accumulation in tissues. The molecular pathogenesis is incompletely understood but it is believed that the growth and proliferation of clonal MC is caused by an activating mutation of the tyrosine kinase receptor Kit for Stem Cell Factor, the main growth factor for MC4.

The clinical features results from the excessive mediator release leading to benign forms of SM or from tissue MC infiltration causing multiorgan dysfunction in more aggressive subtypes of SM 5. Skin involvement is frequent and the forms of presentation include urticaria pigmentosa, diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis, mastocytoma, and telangiectasia macularis eruptive perstans. The diagnosis of SM is possible by the detection of atypical MC, immunohistochemical staining with antibodies positive for tryptase, CD117, CD2 and CD25 or a mutation at codon 816 of KIT, all of these in bone marrow, blood, or other extracutaneous organ, as serum total tryptase > 20 ng/mL. After establishing the diagnosis, it is necessary to define the disease category and the presence of B findings, corresponding to organ enlargement without organ dysfunction and reflecting disease burden, or C findings, associated with a poorer prognosis, denoting organ function impairment due to excessive MC infiltration and reflecting disease aggressiveness.

Skin involvement is frequent and the forms of presentation include urticaria pigmentosa, diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis, mastocytoma, and telangiectasia macularis eruptive perstans. Mediator- related symptoms are a constellation of non-specific signs including fatigue, nausea, vomiting, facial flushing, anaphylaxis, pruritus, abdominal pain, diarrhea, hypotension, syncope and musculoskeletal pain. Cytopenias, hepatosplenomegaly, portal hypertension, lymphadenopathy, hipersplenism, malabsorption, weight loss and pathological bone fractures are results of organ infiltration with neoplastic MC in advanced SM. Patients with mastocytosis are prone to develop bone involvement, which can cause bone pain, diffuse osteopenia, or osteoporosis with fragility or pathologic fractures, diffuse osteosclerosis, or both focal osteolytic and osteosclerotic bone lesions6.

The different skeletal disease patterns in mastocytosis may be due to the ability of mastocytes to infiltrate bone marrow or due to to the effects of MC mediators on osteoblasts and osteoclasts3. It is believed that MC have a propensity to colonize the bone marrow of the most metabolically active bone tissue- trabecular bone, which explains the fact that majority of fractures due to mastocytosis induced osteoporosis occurs at the vertebral bodies3,7,8.

Diagnosis of mastocytosis without skin manifestations can be challenging and bone changes may be the first and the unique manifestation of the disease, therefore SM should be included in the differential diagnosis in cases of osteoporosis in premenopausal women and in men with no other obvious cause of osteoporosis.

Treatment of SM is highly individualized and it depends on the severity of clinical symptoms, patient complaints and on prognosis. Therapeutics options include antimediator therapy, targeted or non-targeted chemotherapies and even allogeneic stem cell transplantation9.

Drugs as antihistamines, leukotriene antagonists, cromoglicic acid and systemic glucocorticosteroids inhibit the release of allergic mediators from MC, while cytoreductive therapy reduces MC load10.

The pathogenesis of bone loss in mastocytosis makes the bisphosphonates as the most suitable for the treatment of the skeletal manifestations in SM. In case of intolerance to bisphoshonate, alternative drugs may be considered as IFN-Alfa or denosumab3. Since pathological fractures are considered C-findings, citoreductive drugs as IFN-Alfa and Cladribine may be considered in patients with SM and severe osteoporosis3. However the opinions regarding a more aggressive approach in these patients vary and treatment decision of skeletal involvement is influenced by a range of factors between them the weight of benefits and risks.

Mastocytosis is a rare condition with unspecific symptoms that may be ignored, especially in indolent cases and this can make the patient to enter into what we call a ´diagnostic odyssey´ and to consult different doctors.

Making the diagnosis of SM without skin involvement remains a challenge, particularly when skeletal changes represent the single manifestation of the disease.

Conclusion

SM is a haematogenous disease characterized by abnormal growth and infiltration of MC in tissues. The bone changes may be the first and the only recognized manifestation of the disease.

The present report describes a case of SM with skeletal manifestation as the sole expression of the disease, that was diagnosed after a histological examination and which made the diagnosis a real challenge.

The key point in diagnosing SM is the awareness of this disorder and it should be included in the differential diagnosis of atypical osteopenia or osteoporosis and osteosclerotic or osteolytic lesions.

Agradecimentos

1. Dra Lara Rodrigues. Unidade de Imagiologia de Hospital Sousa Martins, ULS Guarda

2. Dra. Ana Queirós, Dra. Isabelle Rodrigues Carrilho, Dra. Margarida Farinha. Laboratório de Hematologia de Serviço de Patologia Clínica de Centro Hospitalar Tondela Viseu, EPE.

Figura I

Fracture of L1 vertebra and biconvex aspect of L2 vertebra

Figura II

Bone marrow aspirate with dense aggregates of mast cells

Figura III

Bone marrow aspirate with dense aggregates of mast cells

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Magliacane D, Parente R, Triggiani M. Current Concepts on Diagnosis and Treatment of Mastocytosis. Transl Med UniSa. 2014; 8: 65–74.

2. Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood 2016; 127:2391–2405.

3. Rossini, M., R. Zanotti, G. Orsolini, G. Tripi, O. Viapiana, L. Idolazzi et al. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and treatment options for mastocytosis-related osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 2016; 27:2411–2421.

4. Akin C. Clonality and molecular pathogenesis of mastocytosis. Acta Haematol. 2005; 114:61-9.

5. Vaes M, Benghiat FS, Hermine O. Targeted Treatment Options in Mastocytosis. Front Med. 2017; 4:110.

6. Rossini M, Zanotti R, Viapiana O, Tripi G, Orsolini G, Idolazzi L et al. Bone involvement and osteoporosis in mastocytosis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2014; 34:383–396.

7. van der Veer E, van der Goot W, de Monchy JC, Kluin- Nelemans, van Doormaal JJ. High prevalence of fractures and osteoporosis in patients with indolent systemic mastocytosis. Allergy. 2012; 67:431-8

8.Seitz S, Barvencik F, Koehne T, Priemel M, Pogoda P, Semler J et al. Increased osteoblast and osteoclast indices in individuals with systemic mastocytosis. Osteoporos Int. 2013; 24:2325-34.

9. Arock M, Akin C, Hermine O, Valent P.Current treatment options in patients with mastocytosis: status in 2015 and future perspectives. Eur J Haematol. 2015;94:474-90

10. Onnes MC, Tanno LK, Elberink JN. Mast Cell Clonal Disorders: Classification, Diagnosis and Management. Curr Treat Options Allergy 2016; 3: 453–464