Introduction:

Cutaneous reactions are among the most common adverse effects of drugs. Drug-related rash has been reported for nearly all prescription medications, usually at rates exceeding 10 cases per 1000 new users.1 These reactions can range from asymptomatic mild eruptions to life-threatening conditions.

Severe cutaneous adverse reactions to drugs such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome are idiosyncratic T-cell-mediateddelayed (type IV) hypersensitivity reactions.1

DRESS syndrome, also known as DIHS (drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome) is characterized by rash, fever, lymphadenopathy and internal organ involvement. The incidence ranges between 1 in 1000 and 1 in 10000 exposures.2 Many drugs have been associated with this clinical entity, including allopurinol.

Direct drug toxicity, medication metabolites, immune system, and reactivation of viral infections, particularly human herpesvirus (HHV)-6, are thought to interact to cause this clinical condition that can be fatal and relapse even after an apparently successful treatment.3

The authors report a case of this syndrome presenting with fever, macular rash, hepatitis and renal involvement during allopurinol treatment.

Case Description:

A 65-year-old woman was admitted to the emergency department with generalized pruritic exanthema and fever during the previous 3 days. She had a history of arterial hypertension and dyslipidemia, and was chronically taking nifedipine, perindopril associated with indapamide, simvastatin and aspirin. Three weeks previously to the incident, the patient began treatment with allopurinol for recently diagnosed hyperuricemia. On physical examination at admission she was febrile (39.8ºC) and a maculopapular generalized rash was noted (figures 1 and 2). There was no evidence of mucous membrane involvement, lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. Blood tests showed no alterations on leukocyte counts; serum creatinine level of 1.3 mg/dL (normal range: 0.5-1.2), serum urea level of 88 mg/dL (normal range: 16-42), alanine and aspartate aminotransferases values of 386 and 201 IU/L (normal range: 3-31) respectively, alkaline phosphatase of 319 IU/L (normal range 25-100), gamma-glutamyl transferase of 259 IU/L(normal range 4-32), with normal bilirubin values.

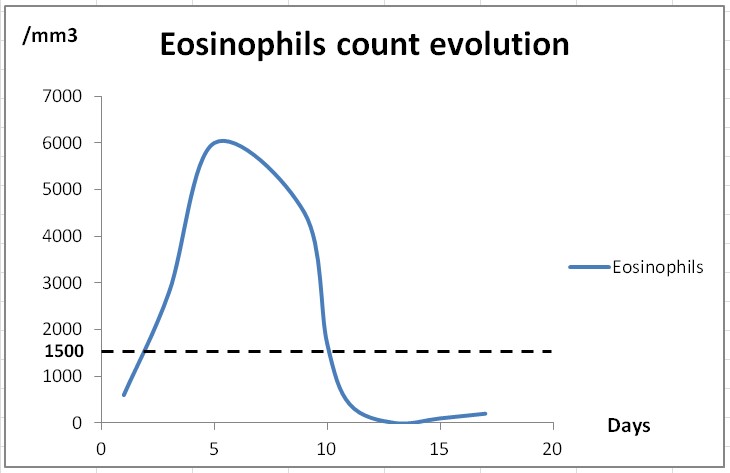

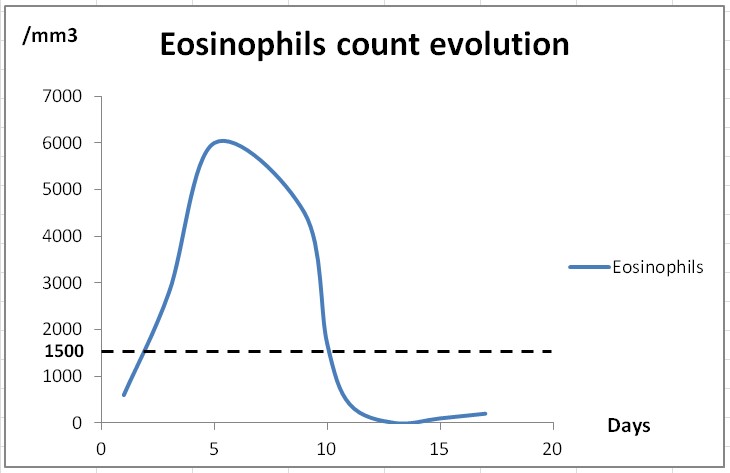

Supportive therapy was provided, and allopurinol was suspended. At the third day of hospitalization, peripheral blood eosinophilia developed (2800/mm3) and the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome was made (Figure 3). Systemic corticosteroid therapy with oral prednisolone (1mg/Kg/day) was started. Daily analytic controls revealed progressive liver function deterioration. Renal involvement was documented by presence of leucocituria and 24-hour proteinuria of 1.29 g without further increase in serum urea nitrogen or creatinine levels.

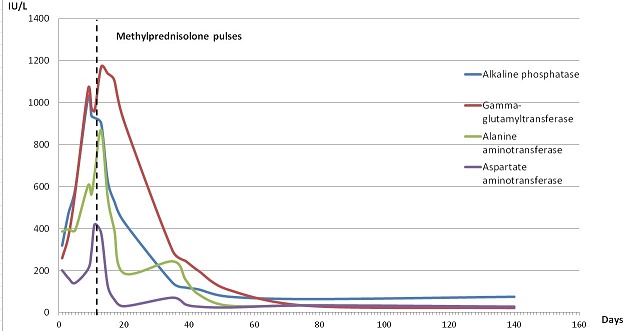

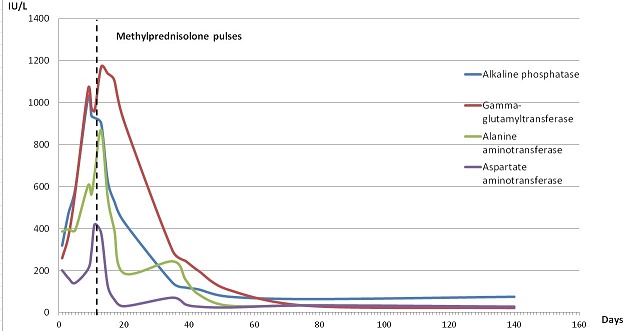

The patient was then treated with a course of pulsed methylprednisolone (1000 mg intravenously for 3 days) with subsequent clinical and analytical improvement (Figure 4).

After 2 weeks of corticosteroid treatment and complete resolution of cutaneous lesions, the patient was discharged. She was kept on steroid therapy in tapered dosages for an additional 2 months.

Further blood workup excluded autoimmune causality. Reactivation of human herpes virus 6 (HHV-6) by polymerase chain reaction was posteriorly confirmed by detection of HHV-6 DNA by polymerase chain reaction and increased titers of IgG anti-HHV-6.

One year later, the patient remains asymptomatic with normal laboratory results.

Discussion:

The aromatic anticonvulsants (phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine) and sulphonamides are the most common drugs causing DRESS syndrome, but a variety of other drugs have been associated including allopurinol.4The onset of the disease usually occurs 2 to 6 weeks after the initiation of the offending drug.4

The pathogenesis is not fully understood. Different mechanisms have been implicated, including detoxification defects leading to reactive metabolite formation and subsequent immunological reactions, slow acetylation, and reactivation of human herpesvirus, including Epstein-Barr virus and human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and 7.2,3,5 The detection of HHV-6 reactivation, that occurs generally 2 to 3 weeks after the onset of the rash, has even been proposed as a diagnostic marker for DRESS.6 In case of allopurinol, the accumulation of oxypurinol, one of its metabolites, seems to be responsible for the initiation of the cascade, especially in the setting of decreased renal function and the concomitant use of thiazide diuretics.7,8 Our patient was taking indapamide and Human herpes virus 6 reactivation was also documented.

The first symptoms are usually fever and rash, which is morbilliform, diffuse, pruritic and macular, and may progress to involve nearly the entire surface of skin.3 There is often significant facial edema.3

Multiple organ systems can be affected in DRESS syndrome. The most common systemic findings involve the lymphatic (lymph node enlargement), hematologic (leukocytosis with eosinophilia and/or atypical lymphocytosis), and hepatic systems, followed by renal, pulmonary, and cardiac manifestations.9

The liver is the most frequently affected visceral organ in DRESS, often with varying degrees of hepatitis, ranging from transitory increase in liver enzymes to liver necrosis with fulminant hepatic failure.9 Hepatitis usually has a mixed hepatocellular and cholestatic pattern,9 as observed in our patient. The kidney is also commonly affected, particularly in allopurinol induced-DRESS.8 In most cases there is only mild renal impairment, which usually resolves after withdrawal of the drug; however severe interstitial nephritis can develop and progress to renal failure.9 In our case there was a slight elevation in serum creatinine at admission with normalization after allopurinol suspension. The presence of leucocituria and proteinuria was consistent with acute interstitial nephritis.

There is no reliable standard for the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome. The diagnostic criteria are based on clinical and laboratory findings. Bocquet et al10 proposed the original criteria to establish the diagnosis, which include the simultaneous presence of all three criteria: 1) cutaneous drug eruption; 2) hematologic abnormalities including eosinophilia greater than 1.5x109 /L or the presence of atypical lymphocytes; and 3) systemic involvement including adenopathy greater than 2 cm in diameter, hepatitis (liver transaminase values >2 ULN), interstitial nephritis, interstitial pneumonitis or carditis. These criteria emphasize two important characteristics: multiple organ involvement and eosinophilia. Other diagnostic criteria have been proposed by the Japanese Research Committee on Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reaction (J-SCAR) group (6) that highlights the role of HHV-6: 1) maculopapular rash developing more than 3 weeks after starting a limited number of drugs; 2) prolonged clinical symptoms 2 weeks after discontinuation of the causative drug; 3) fever greater than 38 ºC; 4) liver abnormalities (e.g., alanine aminotransferase [ALT] levels >100 IU/L); 5) leukocyte abnormalities such as leukocytosis (>11x109/L), atypical lymphocytosis (>5%), and/or eosinophilia (>1.5x109/L); 6) lymphadenopathy; and 7) HHV-6 reactivation. Diagnosis of typical Drug Induced Hypersensitivity Syndrome requires the presence of all 7 criteria; if only the first five are present, atypical DIHS is diagnosed.

Therapy of DRESS syndrome is challenging. Prompt diagnosis is imperative as the offending drug must be immediately discontinued. Supportive therapy includes antipyretics and topical steroids to improve symptoms. Systemic steroids are the most widely accepted therapy in the presence of signs of severity, at a dose of 1 mg/Kg/day of prednisone or equivalent.11 Gradual taper is recommended since significant cutaneous and systemic symptoms have been reported after accidental withdrawal or a rapid reduction in dose.11 A course of pulsed methylprednisolone intravenously for 3 days, can be administered in the cases with no improvement or worsening disease.11 Patients with life-threatening signs can be treated with steroids and adjunctive high dose intravenous immunoglobulin.11 In our patient, as there was no improvement with oral corticosteroids, we tried methylprednisolone pulses with very good response.

DRESS is a potentially life-threatening drug reaction, with an estimated mortality rate of 10%, mostly due to liver failure.4 Culprit drug may influence the outcome of DRESS. The death rate in patients with allopurinol-associated DRESS syndrome seems to be higher than that described in cases resulting from other drugs.5 Most patients have complete recovery after drug withdrawal, but some suffer long term sequelae as a result of extensive systemic damage.9 There are also reports relatingDRESS syndrome with autoimmune diseases such as thyroid disease, sclerodermoide lesions and systemic lupus erythematosus.9 Thus, it is important to routinely monitor these patients after DRESS syndrome diagnosis.

Conclusions:

DRESS syndrome is a potentially life-threatening drug reaction associated with a variety of drugs namely allopurinol, being liver involvement the most common visceral manifestation in DRESS syndrome and hepatic failure the main cause of death.

Early recognition of DRESS syndrome with suspension of the offending drug is the keystone of treatment, but systemic corticosteroids associated to intravenous immunoglobulin may be needed in patients with severe disease.

Figura I

Coalescent maculopapular eruption in the arm.

Figura II

Morbiliform rash in the lower limbs, that over the time became purplish.

Figura III

Graphic representation of the evolution of eosinophil count in peripheral blood. The cut off value of 1500 eosinophils/mm3 is used in DRESS syndrome diagnostic scores.

Figura IV

Evolution of hepatic enzymes. The dashed line corresponds to the administration of intravenous methylprednisolone pulses.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1.Stern RS. Clinical practice: Exanthematous drug eruptions. N Engl J Med. 2012 Jun 28;366(26):2492-501.

2.Criado PR, Avancini J, Santi CG, Medrado AT, Rodrigues CE, de Carvalho JF. Drug reaction with eosinofilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): a complex interaction of drugs, viruses and the immune system. Isr Med Assoc J. 2012 Sep;14(9):577-82.

3.Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part I. Clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 May;68(5):693.

4.Cardoso CS,Vieira AM,Oliveira AP. DRESS syndrome: a case report and literature review. BMJ Case Rep.2011 Jun 3;2011.

5.Cacoub P,Musette P,Descamps V,Meyer O, Speirs C,Finzi L,Roujeau JC. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med.2011 Jul;124(7):588-97.

6.Shiohara T,Inaoka M,Kano Y. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS): a reaction induced by a complex interplay among herpesviruses and antiviral and antidrug immune responses. Allergol Int. 2006 Mar;55(1):1-8.

7.Shalom R, Rimbroth S, Rozenman D, Markel A. Allopurinol-induced recurrent DRESS syndrome: pathophysiology and treatment. Ren Fail. 2008;30(3):327-9

8.Markel A. Allopurinol-induced DRESS syndrome. Isr Med Assoc J. 2005 Oct;7(10):656-60.

9.Kano Y, Ishida T, Hirahara K, Shiohara T. Visceral involvements and lon-term sequelae in drug-induced hypersensivity syndrome. Med Clin North Am. 2010 Jul;94(4):743-59.

10.Bocquet H, Bagot M, Roujeau JC. Drug-induced pseudolymphoma and drug hypersensivity syndrome (Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms: DRESS). Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1996 Dec;15(4):250-7

11.Husain Z,Reddy BY,Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part II. Management and therapeutics. J Am Acad Dermatol.2013 May;68(5):709.