Cellulitis is a common infection, affecting the face in 4-24% of the cases. Its main pathogens are Gram positive bacteria, but the etiology in the head and face are more difficult to ascertain since they are frequently excluded from the studies. Historically, the most serious complications is septic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, however prospective studies are lacking.1,2,3

A 41-year-old female patient with no prior medical history presented to the emergency department complaining of a 2-day fever and worsening painful facial edema which originated from a herpetic lip lesion she had manipulated.

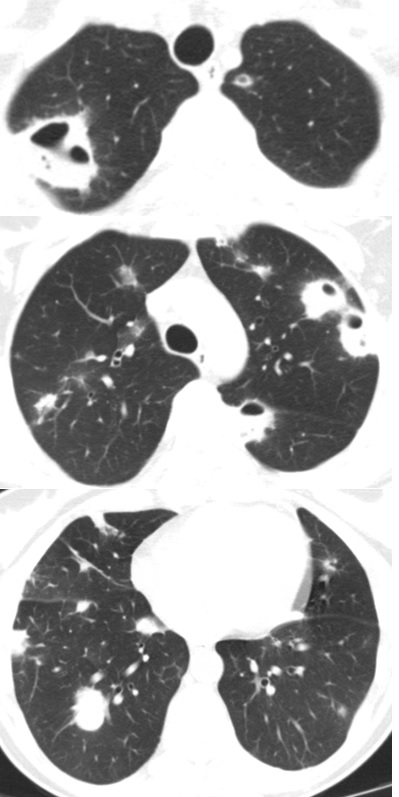

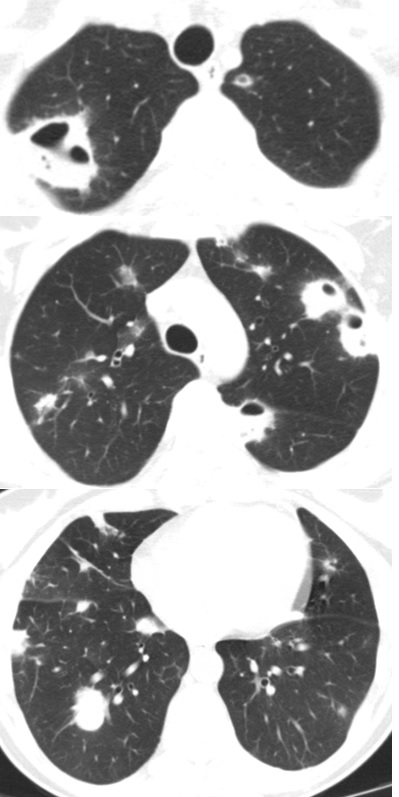

The patient underwent cranioencephalic computed tomography (CT) scan confirming facial cellulitis, was admitted (blood cultures obtained) and started on intravenous Amoxicillin and Clavulanic Acid and Metronidazol. She gradually improved but developed productive cough (purulent sputum) after 2 days that progressed to hemoptysis, new onset fever and a rise in the inflammatory analytical parameters. CT showed progression of the cellulitis with signs of facial myositis and multiple nodular cavitated lung lesions with air-fluid level (figure 1) suggestive of abcesses. New cultures (blood and sputum) were obtained, echocardiogram excluded endocarditis and the patient was started on piperacillin/tazobactam. A bronchoalveolar lavage identified a methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus allowing the de-escalation to Flucloxacillin.

A neck doppler showed partial thrombosis of the external jugular vein, suggesting a process similar to Lemierre syndrome and explaining a pathophysiological pathway to a septic embolization.2,4

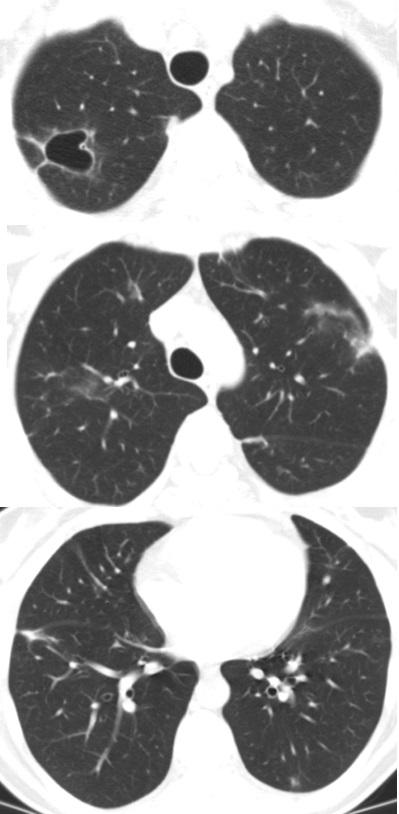

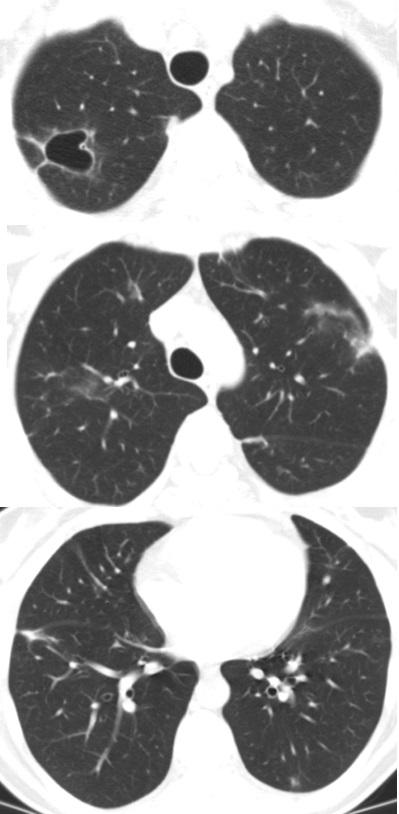

A thorax CT (2 months after the first) showed a sequelar cavitated lesion and regression of the others (figure 2).

It is often recommended that facial cellulitis be admitted to hospital because the most grievous complication, albeit a rare one, can be catastrophic, but avoidable with timely antibiotherapy. Other complications cannot be disregarded since Staphylococcus aureus infections can have an aggressive evolution including the ability to destroy tissues provoking sequelar complications.1,2,3,5

Figura I

Figura II

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1 - Eivind Rath, Steinar Skrede, Haima Mylvaganam & Trond Bruun (2017): Aetiology and clinical features of facial cellulitis: a prospective study, Infectious Diseases, DOI: 10.1080/23744235.2017.1354130

2 - Wong, KS; Lin, TY; Huang, YC; Hsia, SH; Yang, PH; Chu, SM. Clinical and radiographic spectrum of septic pulmonar embolism. Arch Dis Child. 2002; 87:312–315

3 - Liu, C; Bayer, A; Cosgrove, SE; Daum, RS; Fridkin, SK; Gorwitz, RJ; Kaplan, SL; Karchmer, AW; et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2011.

4 - Chirinos JA, Lichtstein DM, Garcia J, Tamariz LJ. The evolution of Lemierre syndrome: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002; 81:458.

5 - Miranda, I; Barreiros, C; Silva, RC; Torre, E; Rodrigues E; Guerra, D; Pinto, A. CELULITE POR MRSA DA COMUNIDADE COM EMBOLIZAÇÃO PULMONAR SÉPTICA, Revista online de casos clínicos em Medicina Interna, 2017