Introduction

Mediterranean spotted fever (MSF) is an endemic zoonosis in the Mediterranean basin1. Clinical presentation can be highly variable ranging from non-specific symptoms to the classical triad of fever, rash and headaches.

Hemophagocytic syndrome (HS) results from an uncontrolled inflammatory response and it can be triggered, among other causes, by infections. The diagnostic criteria were proposed in 1991, updated in 2004, and they include fever; splenomegaly; cytopenia affecting at least 2 of 3 lineages in the peripheral blood; hyperferritinemia; hypertriglyceridemia; hypofibrinogenemia; hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow, spleen, or lymph nodes; low or absent NK-cell activity and high levels of soluble CD25 (sCD25)2. Five of eight criteria are required for diagnosis2. We describe a case of HS that occurred as a complication of MSF.

Clinical case

A previously healthy 31-years-old white-European man was admitted in July of 2017 to the emergency department, with a 5 days history of intense headache, chills, fever (39ºC), myalgia and arthralgia, with no other symptoms. He denied any use of medications, tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs. He was born and lived all his life in a rural village. The patient reported engagement in agricultural works and direct contact with a vaccinated dog and cat. There was no history of tick or flea bite, foreign travel or ingestion of row meat or unpasteurized milk.

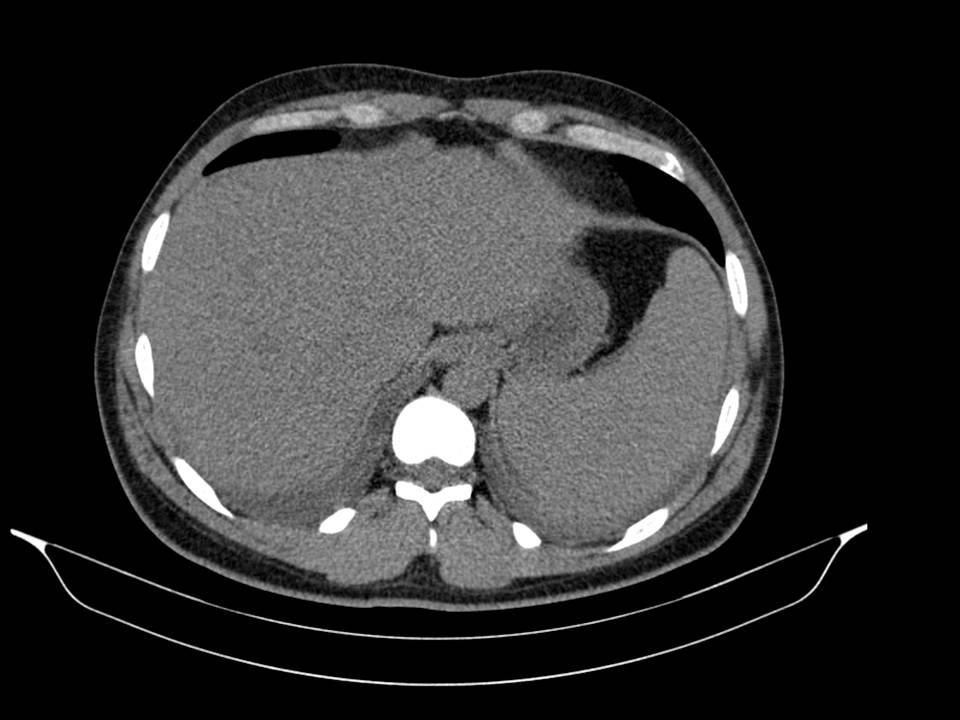

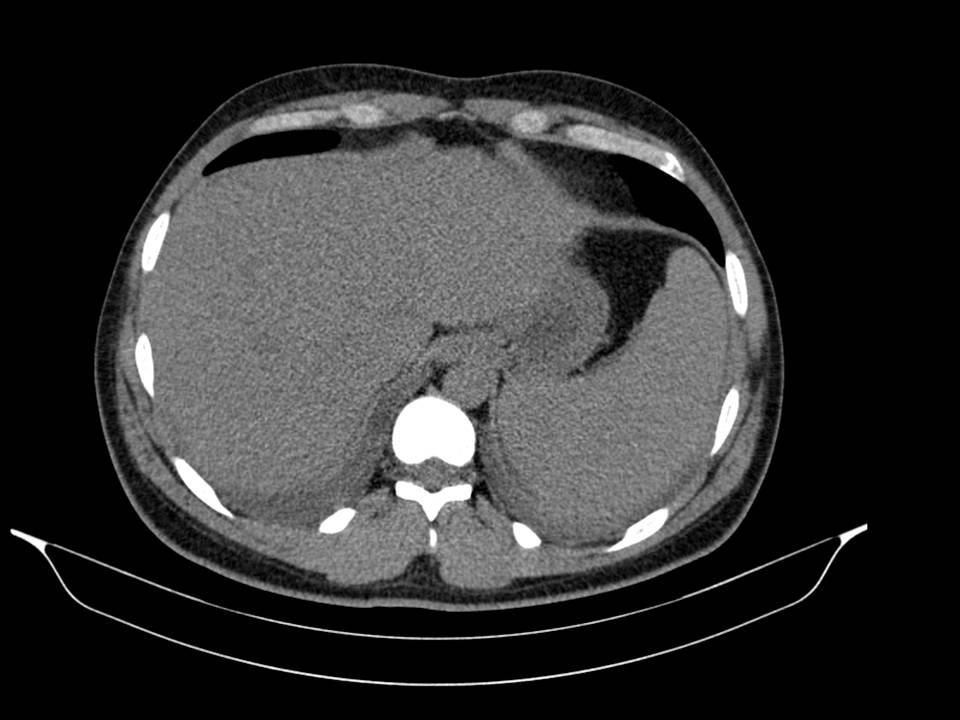

On examination he appeared sweaty, feverish (39,7ºC), and it was identified splenomegaly of about 3 cm below the costal margins, with no palpable lymph nodes.

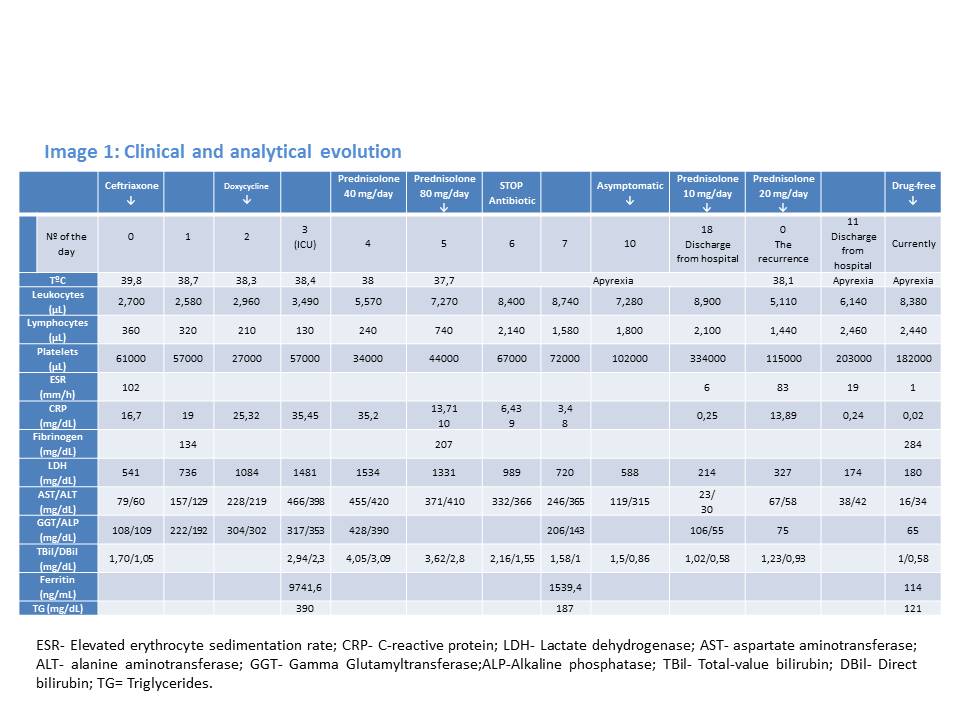

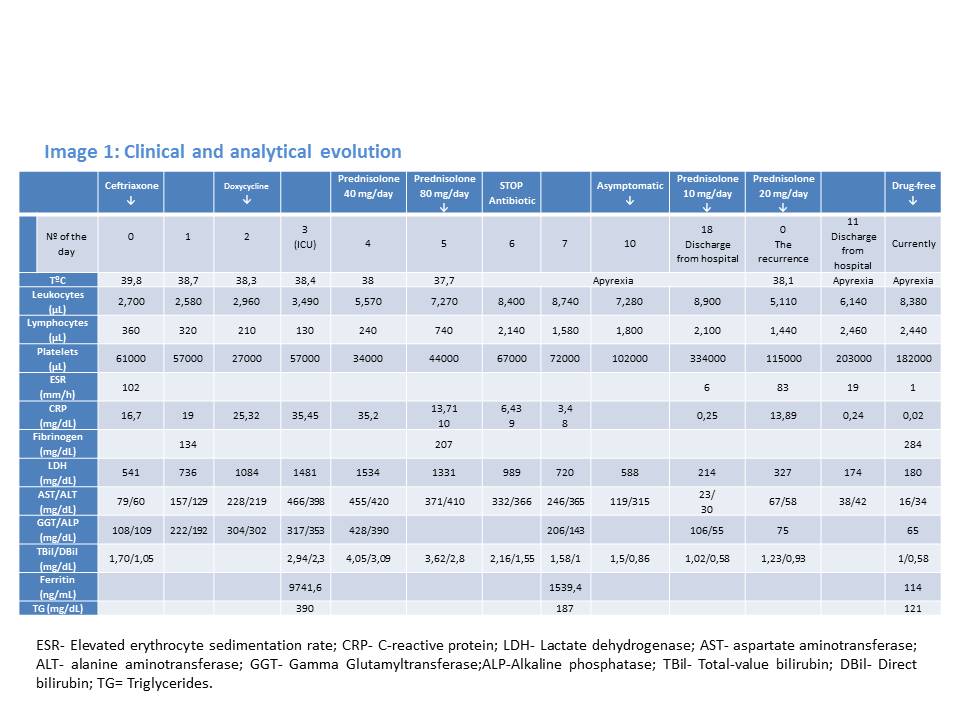

The patient´s laboratory results (Image 1) revealed bicytopenia (lymphopenia with thrombocytopenia) and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). It was also detected elevated liver function tests (LFTs) with mild hyperbilirubinemia, high lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and low fibrinogen - 126 mg/dl. Serologies for Mycoplasma, Brucella, Legionella, Borrelia, Salmonella, Q fever, spotted fever, HIV, EBV, CMV, hepatitis A, B, and C, parvovirus B19, Leishmania, Hantavirus, Toxoplasma, Bartonella henselae and West Nile were all negative. Multiple cultures of blood and urine were negative for bacteria, mycobacteria and fungi. He was admitted to the in-patient internal medicine department and started on empiric antibiotic therapy with ceftriaxone 2g once daily.

The patient continued to have daily spiking fevers and sweats, with worsening of the cytopenias, coagulation defects and LFTs. A generalized maculopapular rash sparing the face, palms and plants appeared on the 2nd day. This new clinical manifestation, together with the existence of an epidemiological context, led to the association of Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily.

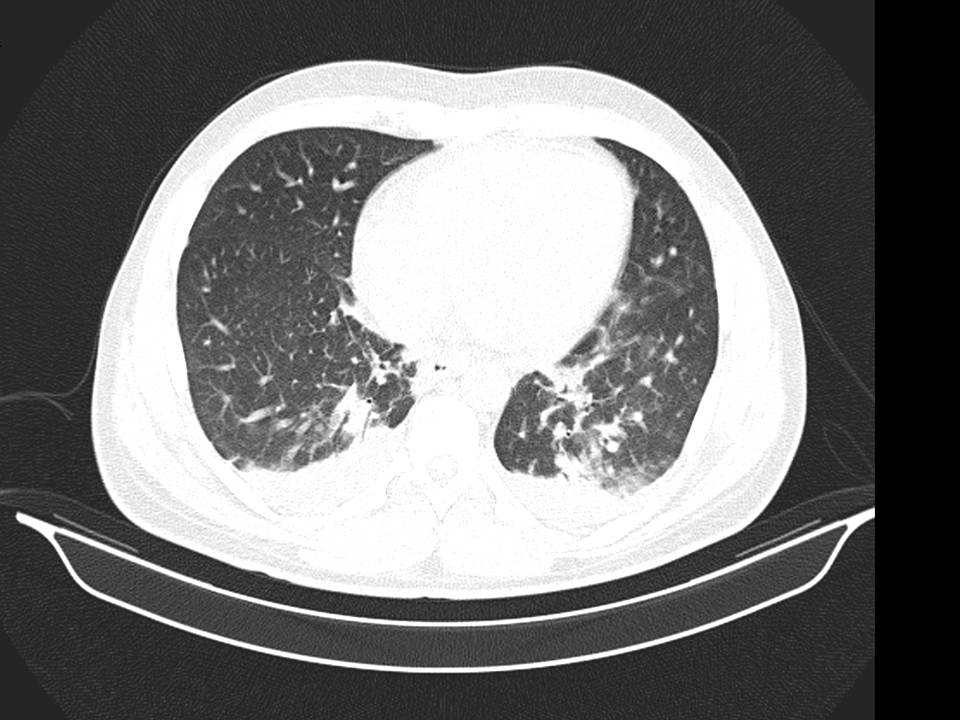

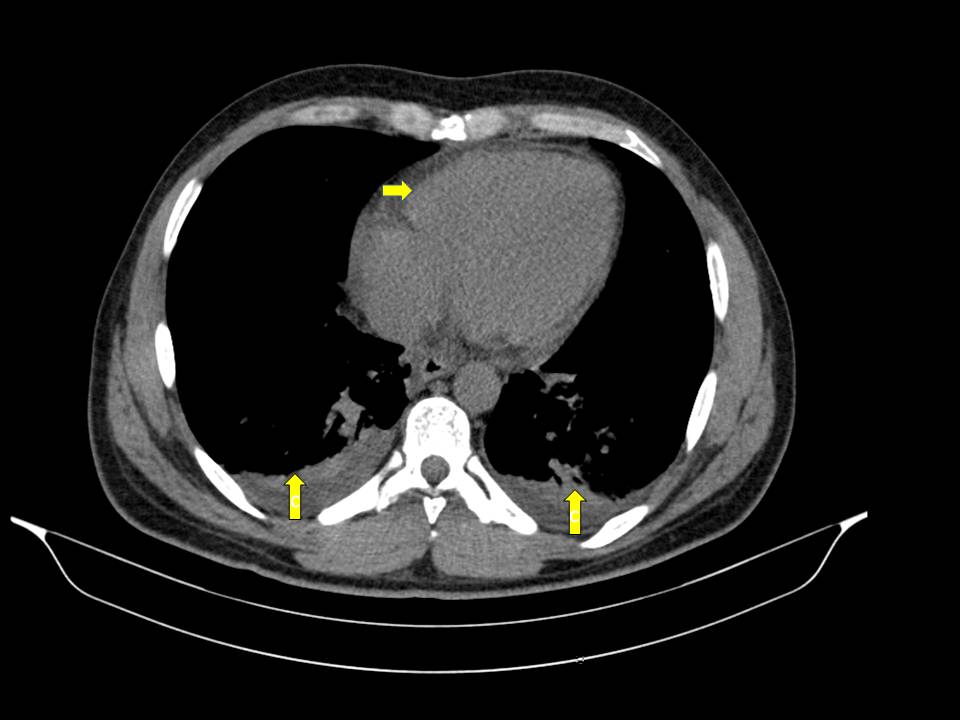

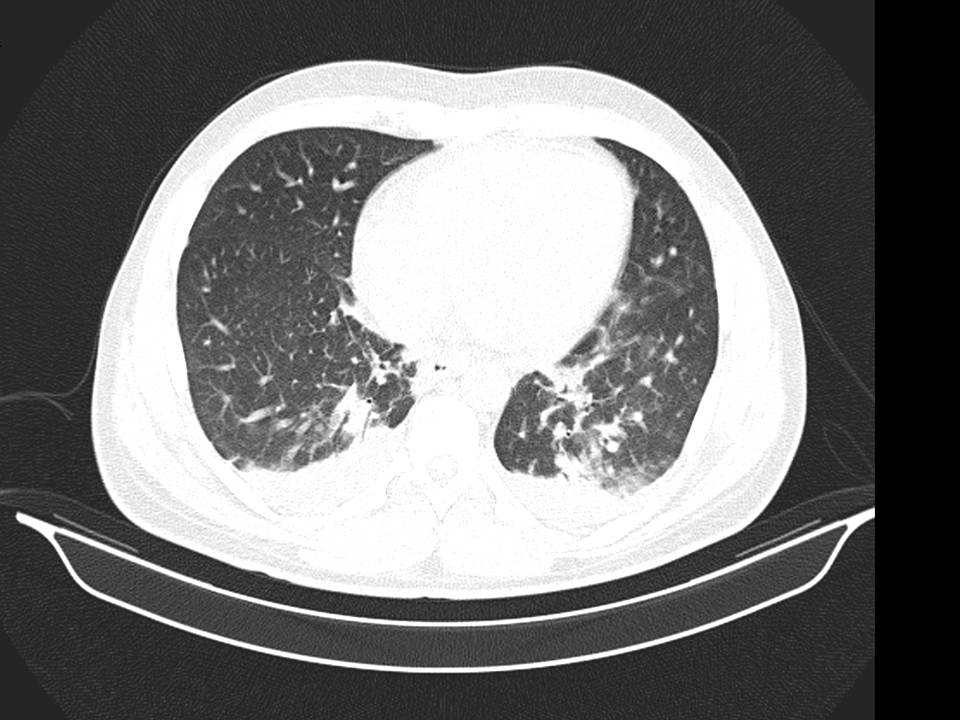

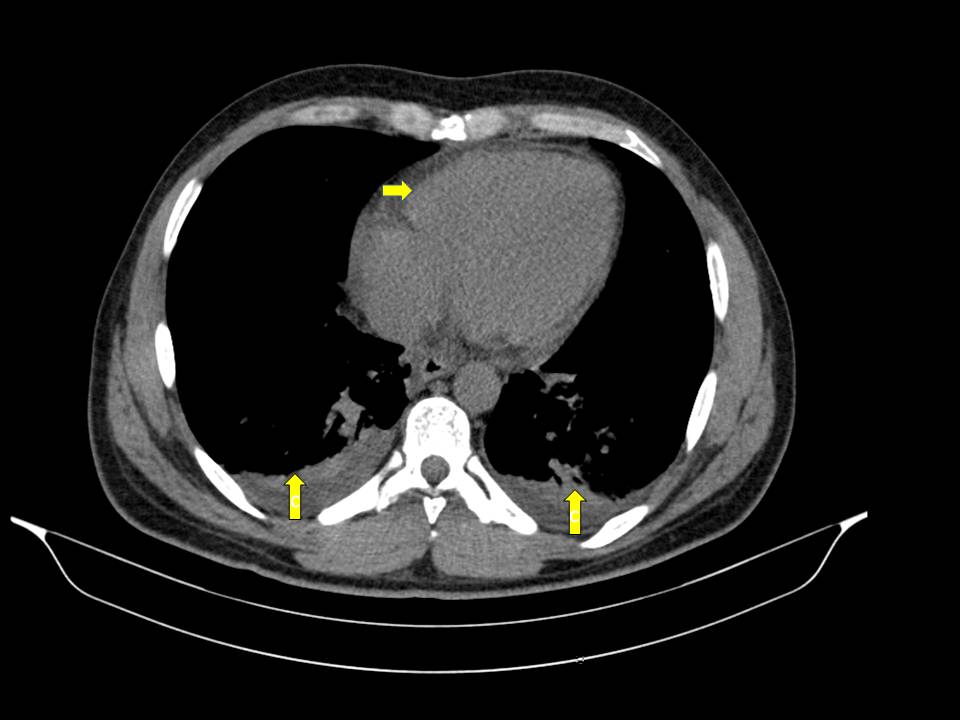

No improvement of clinical status was observed. On the contrary, we identified hypoxemia (PaO2/FiO2= 280), aggravation of cytopenias, LFTs and of LDH. The chest-abdomen-pelvis computed tomography showed interstitial pulmonary infiltrates, mild pleural and pericardial effusion (Image 2 and 3), homogeneously enlarged liver and spleen (Image 4) and the echocardiography revealed mild pericardial effusion with normal ventricular function and no valvular abnormalities. Additional blood tests showed significant increase of serum ferritin and triglycerides (TG); the autoimmune study was negative (including anti-nuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmatic antibody, anti-cardiolipin and anti-beta-2 glycoprotein antibodies) as well as direct Coombs test. The patient refused spleen or bone marrow biopsy. He was transferred to Intensive Care Unit (ICU), on the 3rd day of hospital admission, with the diagnosis of Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome and initiated systemic steroids- Prednisolone 0.5 mg/kg/day, with improvement of the bicytopenia, LFTs, LDH, ESR and CRP. However, on the 3th day after admission to ICU the young man presented blurred and diminished vision, suggestive of retinal vasculitis on fundus fluorescein angiography and the dose of Prednisolone was increased to 1mg/kg/day. The patient became completely asymptomatic 5 days after the admission to ICU. A course of 7 days of Ceftriaxone and 5 days of Doxycycline was completed. An autoimmune disorder or a secondary HS was suspected. So, a new diagnostic workup was made, including serum level of sCD25, this one elevated (5139 pg/mL), and serology for Brucella, MSF, EBV and CMV, all of these with pending results at the time of discharge. He returned to the Internal Medicine Ward on 20 mg/day of Prednisolone and he was discharged from the hospital 19 days after admission, with no abnormalities on physical examination or blood tests, and invited to a follow up consultation 2 weeks after the discharge. One week after the discharge he returned to the emergency department with milder headache and low fever. The physical examination was irrelevant and the blood tests showed mild thrombocytopenia, elevated ESR and CRP (Table 1). The review of the serological tests from the previous episode revealed positive IgM antibodies to Rickettsia conorii; Doxycycline was restarted and a course of 14 days was completed. A complete resolution of symptoms occurred within 3 days and complete withdrawal of steroids was made 1 month after this episode. Four weeks after the illness onset, the IgG titer to Rickettsia conorii showed a rise more than four-fold of normal value.

Hence, the diagnosis of MSF was confirmed and criteria of HS, the last one secondary to Rickettsiose, were fulfilled.

Currently the patient maintains follow up in the out-patient ward of Internal Medicine, he remains absolutely asymptomatic and drug-free. Recent imagiological exam revealed no serositis or hepatosplenomegaly.

Discussion

Rickettsioses are zoonotic infections caused by gram- negative obligate intracellular bacteria of the genera Rickettsia and Orientia, transmitted to humans via arthropods1. Firstly described by Conor and Brush in 1910 in Tunisia, the MSF, also called boutonneuse fever, is an endemic zoonosis in the Mediterranean area caused by Rickettsia conorii, with summer outbreaks between May and October. The main vector is the brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus3.

The pathogenesis of MSF is a vasculitis, caused by bacteria proliferation in the endothelial lining of small vessels. All the organs can be involved in untreated patients4. The ocular involvement is frequent, usually asymptomatic, self-limited and, therefore, easily overlooked5.

After an average incubation period of 7 days, the disease presents with fever and myalgia/arthralgia during 3-5 days, followed by maculopapular rash involving palms and plants. An indolent inoculation scar (“tache noire”) can be identified, usually located on the trunk and extremities1.

In most cases, the clinical course of Ricketsia conorii infection is benign, with a slow recovery, and an overall fatality rate close to 2.5%1.

The clinical diagnosis confirmation can be achieved in four basic ways: isolation of the organism, serology, polymerase chain reaction detection of DNA and immunologic detection in tissue samples6. Antibody is variably absent for 1 to 2 weeks after onset of symptoms and an initial negative titer should not be used to exclude the diagnosis of rickettsial disease, thus a second serum specimen should be drawn 1 to 2 weeks later to establish the diagnosis in such patients6.

HS, originally described by Scott and Robb-Smith, is a life-threatening entity characterized by overwhelming inflammation related to uncontrolled activation of macrophages and T-lymphocytes and cytokine storm.

Although widely used, the diagnostic criteria proposed by Histiocyte Society2have never been validated in the reactive form of the syndrome. Alternatively, Fardet et al7proposed new criteria for the diagnosis of secondary HS, called HScore, which include nine variables (known underlying immunosuppression, high temperature, organomegaly, triglyceride, ferritin, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase, fibrinogen levels, cytopenia and hemophagocytosis features on bone marrow aspirate). The sum of the points assigned to each variable corresponds to a probability of secondary HS ranging from <1% with an HScore of ≤90 to >99% with an HScore of ≥250.

Good outcomes are described in HS secondary to MFS, although the last one represents a rare infectious cause of HS8-9. Regarding the treatment, usually no immunosuppressive treatment is necessary in MSF-associated HS and complete recovery has been attained with antibiotic treatment in almost all patients9.

Our patient fulfilled 6 of 8 criteria for the diagnosis of HS according to Histiocyte Society2 (fever, splenomegaly, bycytopenia, hyperferritinemia, hypertriglyceridemia, hypofibrinogenemia and high sCD25). And according to criteria proposed by Fardet et al7, in our patient the probability of having HS was 99,86 % with an HScore of 274.

So, is this a primary or a secondary syndrome? The previous history of complete health, the abrupt onset of fever and flu-like symptoms, the rash and the epidemiologic context, all argue for a secondary etiology, namely a zoonosis.

The lack of lymphadenopathies and the absence of atypical cells in the peripheral blood, as well as the unremarkable autoimmune serologies make hematologic malignancy or autoimmune disease less likely. Besides that, primary hemophagocytosis is practically nonexistent at this age.

In our opinion, this particular case of MSF complicated with HS, mainly due to a delay in the patient treatment. The atypical rash (sparing face, palms and soles), the lack of tick bite history, the absence of the inoculation scar and the negative serological results for Rickettsia conorii at admission to hospital were confounding elements. On the other hand, the course of Doxycycline was too short, and it should be continued for at least 3 days after symptoms resolution, in order to avoid fever and thrombocytopenia recurrence.

HS and symptomatic ocular involvement do not represent common clinical features of MSF, making the diagnosis even more challenging.

Conclusion

Rickettsioses have marked tropism for the small vessels endothelial cells, leading to a vasculitis process with variable clinical presentations, which are commonly misdiagnosed, even in endemic areas. An array of ocular changes has been associated with MSF, most of them usually self-limited and easily overlooked.

We highlight the physicians need to be alert for the MSF diagnosis, mainly in spring and summer seasons and that the initial diagnosis must be purely clinical. The treatment must be instituted early despite negative serological results on initial screening.

The presence of respiratory distress, multiorganic dysfunction or profound cytopenia should recall for hemophagocytosis diagnosis.

Figura I

Clinical and analytical evolution

Figura II

Pulmonary Interstitial infiltrates

Figura III

Pleural and pericardial effusion

Figura IV

Splenomegaly without focal lesions

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Faccini-Martínez ÁA, García-Álvarez L, Hidalgo M, Oteo JA. Syndromic classification of rickettsioses: an approach for clinical practice. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;28:126-39.

2. Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124-31.

3. Meireles M, Magalhães R, Guimas A. Mediterranean Spotted Fever: Retrospective Review of Hospitalized Cases and Predictive Factors of Severe Disease. Acta Med Port. 2015;28:624-31.

4. Leone S, De Marco M, Ghirga P, Nicastri E, Lazzari R, Narciso P. Retinopathy in Rickettsia conorii infection: case report in an immunocompetent host. Infection. 2008;36:384-6.

5. Kahloun R, Gargouri S, Abroug N, Sellami D, Ben Yahia S, Feki J et al. Visual Loss Associated with Rickettsial Disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2014;22:373-8.

6. Febre Escaro-Nodular. Consensos em Infecciologia Pediátrica. Acta Pediatr Port 2005;5:257- 263.

7. Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, Marzac C, Aumont C, Chahwan D et al. Development and validation of the hscore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:2613–20.

8. Hsairi M, Ben Ameur S, Alibi S, Belfitouri Y, Maaloul I, Znazen A et al. Macrophagic activation syndrome related to an infection by Rickettsia conorii in a child. Arch Pediatr. 2016;3:1076-1079.

9. Lecronier M, Prendki V, Gerin M, Schneerson M, Renvoisé A, Larroche C et al. Q fever And Mediterranean Spotted fever associated with hemophagocytic syndrome: case study and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17(8):e629-33.