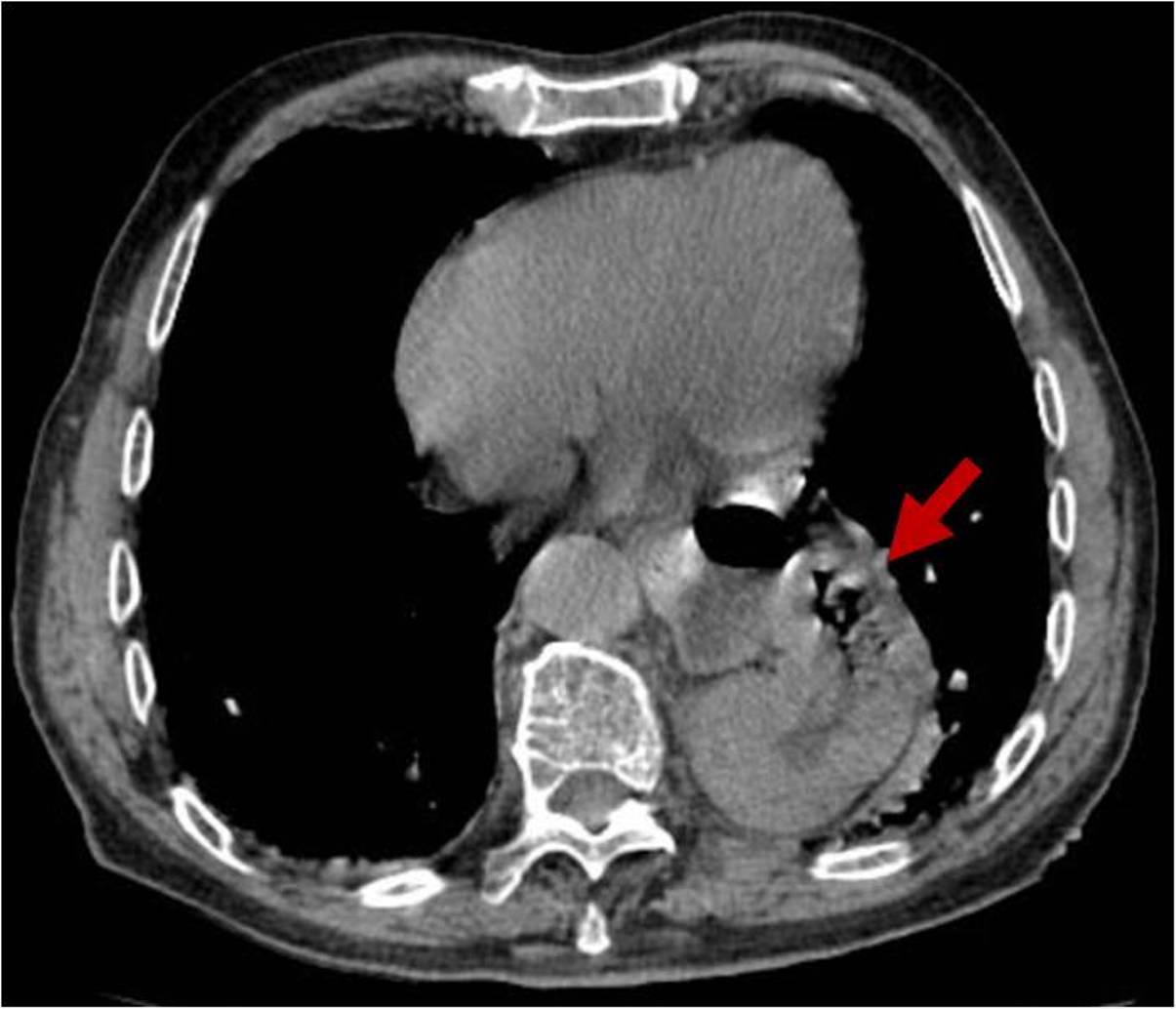

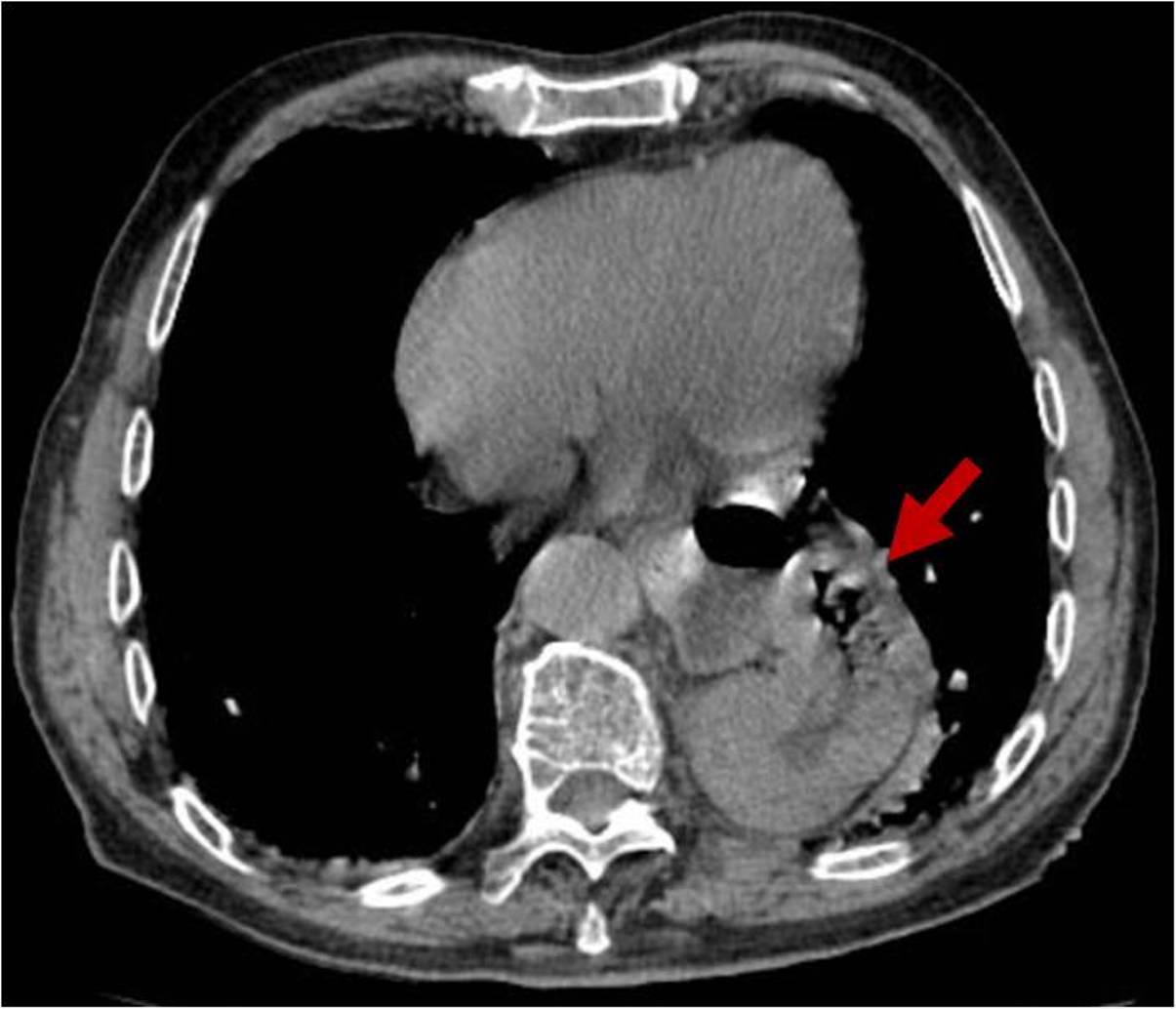

An 85-year-old man with a history of psychiatric disorder and ferropenic anemia of unknown duration presented to the emergency department for an episode of transient hypotension and peripheral cyanosis. Anamnesis revealed occasional presyncopes with no identifiable cause and clinical examination was unremarkable, except for asymmetrically diminished breath sounds. Electrocardiogram demonstrated a normal sinus rhythm. Laboratory assessment confirmed the previous record of anemia, without other abnormalities. Anteroposterior chest radiograph showed a rounded opacity in paramedian location most prominent in the lower left hemithorax, with a well-defined cardiac border (Fig. 1), suggesting a large retrocardiac mass. Computed tomography of the thorax further revealed an intra-thoracic location of the entire stomach, consistent with an uncomplicated hiatal hernia (Fig. 2). The patient was managed conservatively.

Hiatal hernias are more common in the elderly. Most are asymptomatic and discovered accidentally.1 An elicited vasovagal reflex and mucosal damage leading to iron deficiency in the absence of acute gastrointestinal bleeding2,3 could explain this patient symptoms, once other causes were excluded. Alternatively, left atrial compression with hemodynamic compromise by a dilated hernia sac, namely following large meals, is a rare cause for presyncope and syncope better conceivable in this setting.4

However, despite its usual unspecific presentation, hiatal hernias may cause serious complications, such as esophageal adenocarcinoma or perforation.1 Particularly, larger displacements increase the risk of acute gastric volvulus, a rare but potentially life-threatening condition that is characterized by a challenging diagnosis and delayed management, thus requiring a high index of suspicion.5,6

Previous awareness of a large hiatal hernia could therefore help prompt recognition of such an emergency.

The present case illustrates how a careful interpretation of chest radiographs can be of paramount importance in the detection of relevant clinical problems, not typically contemplated in the main differential diagnosis. Tomography is essential to subsequently assess the evoked hypothesis.

Figura I

Anteroposterior chest radiograph

Figura II

Computed tomography axial image

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Yu HX, Han CS, Xue JR, Han ZF, Xin H. Esophageal hiatal hernia: risk, diagnosis and management. Expert Review of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Taylor & Francis; 2018. 319-329 p.

2. Lee YY, McColl KEL. Pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27(3):339ľ51.

3. Wo JM. Treatment of older patients with hiatal hernia. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2008;4(2):97ľ8.

4. Walpot J, Amsel B, Pasteuning WH, Hokken R. Left atrial compression caused by hiatus hernia: a rare cause of syncome. Acta Clin Belg; 2011 Nov-Dec; 66(6):422-5.

5. Rashid F, Thangarajah T, Mulvey D, Larvin M, Iftikhar SY. A review article on gastric volvulus: A challenge to diagnosis and management. Int J Surg. Elsevier Ltd; 2010;8(1):18ľ24.

6. Chen DP, Walayat S, Balouch IL, Martin DK, Lynch TJ. Abdominal pain with a twist: a rare presentation of acute gastric volvulus. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. Taylor & Francis; 2017;7(5):325ľ8.