Background

Even though rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is commonly presented as a disease that affects the joints, it is a truly systemic disease which can have many extra-articular manifestations, namely respiratory.1 Spontaneous hydropneumothorax is a rare manifestation of pleural disease, which is frequently related to rheumatoid lung nodulosis.2

Methotrexate is a folate derivative used in RA treatment which as been linked to rheumatoid nodulosis. This case intends to describe a rare complication of RA and speculate about the aforementioned relationship.

Case presentation

We report the case of a 78-year-old female patient with recent diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis and a high burden of co-morbidities (moderate aortic stenosis, previous cerebral infarction related right hemiparesis, mild vascular dementia and type 2 diabetes mellitus).

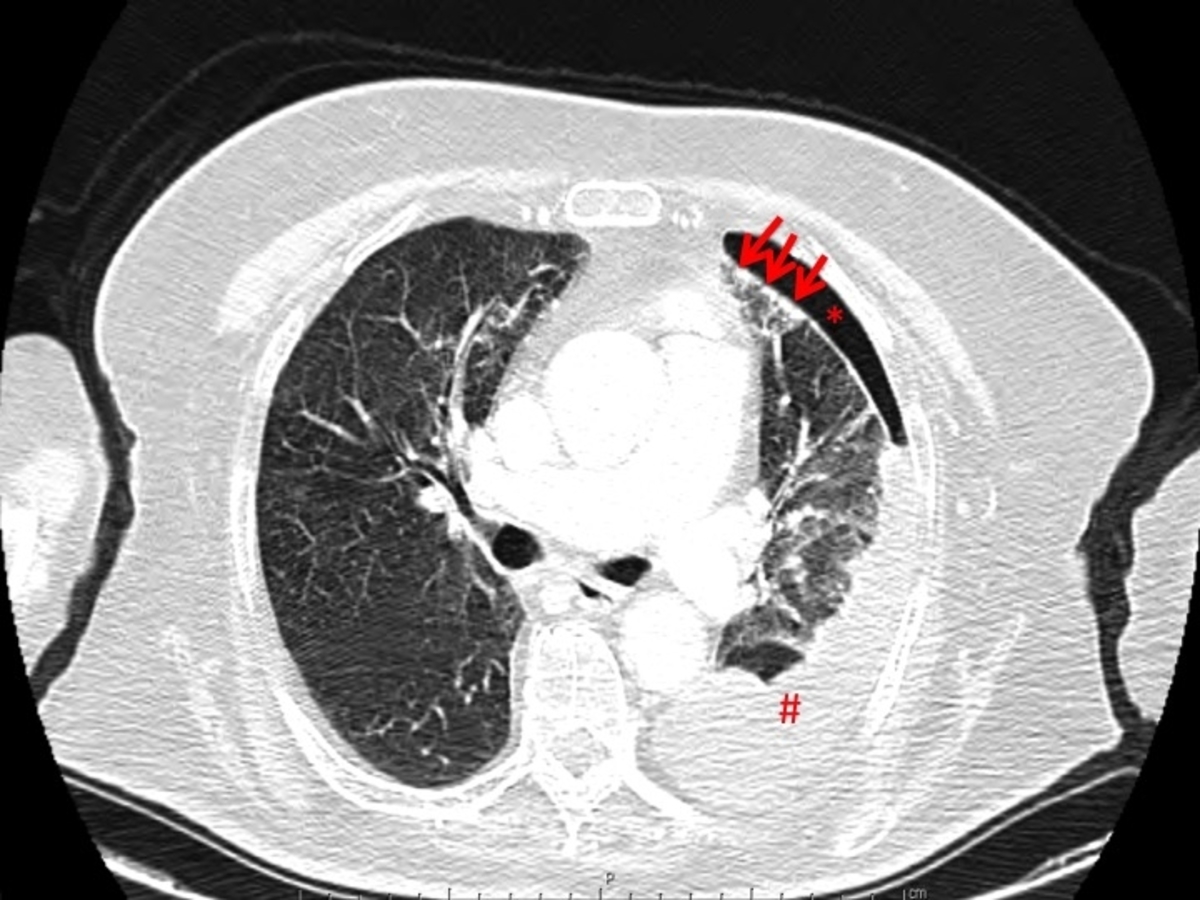

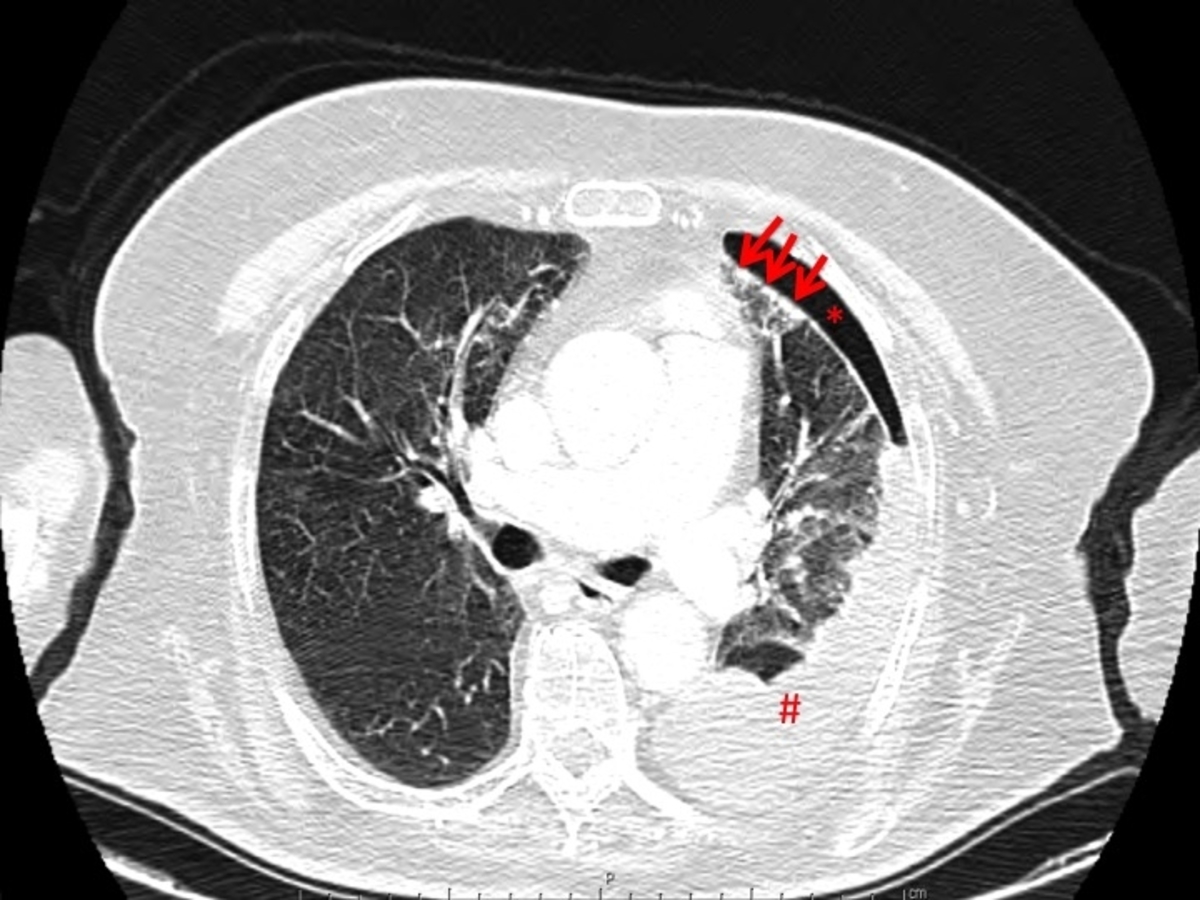

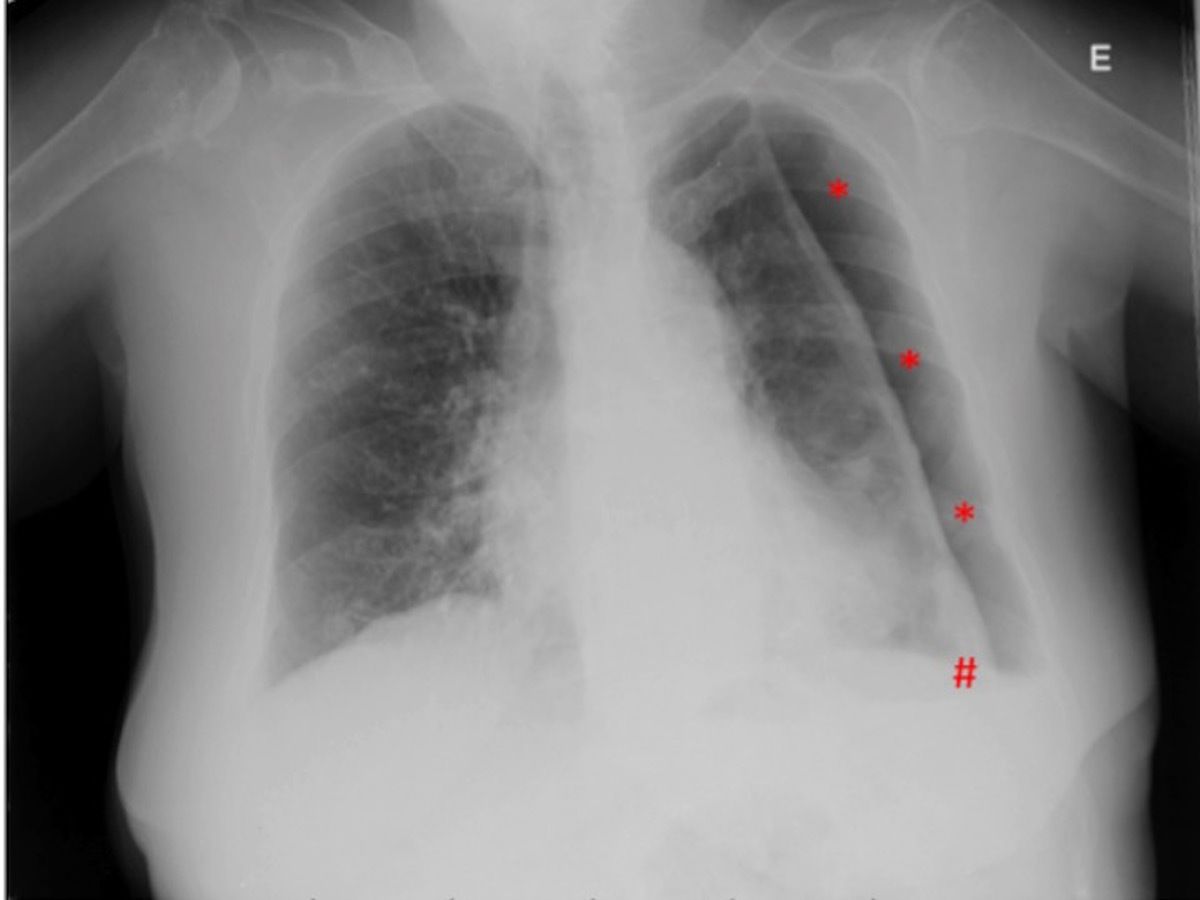

During the follow-up, in outpatient setting,arthralgia and inflammatory markers were very difficult to manage and the pharmacological therapy had to be rapidly escalated to prednisolone 7.5mg qd and methotrexate 17.5mg/week for symptom control. Nonetheless, the inflammatory markers kept high (erythrocyte sedimentation rate >100 mm/h and C- reactive protein 50 mg/dL) which required a new chest-abdomen-pelvis computed tomography scan, to search for uncontrolled systemic disease, which revealed left hydropneumothorax (figure 1.). The patient was immediately called for admission on Medical Ward. At admission she declared to be asymptomatic.

At day 1, the patient underwent thoracentesis which revealed a cloudy yellow pleural fluid with pH 7.05, lactate dehydrogenase > 4000 U/L, glucose consumption (96%) and elevated adenosine deaminase (88.5 U/L). Cytology showed a polymorphonuclear predominant pleural fluid with no apparent malignant cells. Microbiological analysis was negative (including for mycobacteria). It was assumed that the spontaneous hydropneumothorax was related to peripheral lung rheumatoid nodulosis. We decided for conservative approach. Methotrexate was withheld.

At day 7, due to persistence of high inflammatory markers and refractoriness of the hydropneumothorax, it was decided to proceed to pleural drainage and biopsy (to exclude other aetiologies like malignancy and pleural tuberculosis). Later on, the pleural biopsy revealed an inflammatory polymorphic infiltrate with abundant fibrin deposit. No signs of malignancy or mycobacteria growth in culture were shown.

At day 17, after confirmation of hydroneumothorax resolution, the patient was discharged. After multidisciplinary meeting it was decided that, since the inflammatory markers where still high, methotrexate 17.5 mg/week should be reintroduced.

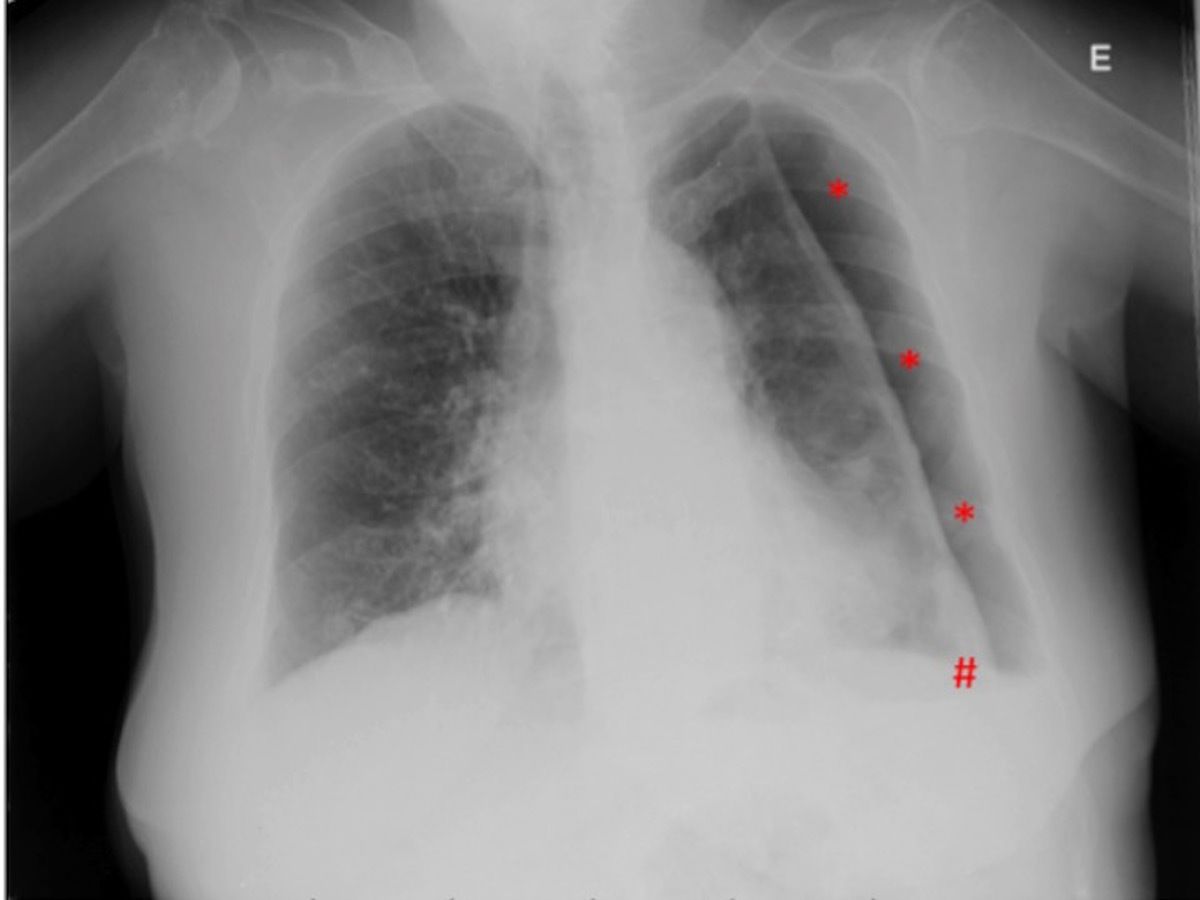

In outpatient setting, the patient was proposed for biological therapy but was rejected because of her co-morbidities and frailty. One month after discharge new asymptomatic left hydropneumothorax was detected in routine chest X-ray (figure 2.) and she was re-admitted for pleural drainage.

Eighteen days later, the pneumothorax chamber was residual and an uneventful chest tube talc slurry pleurodesis was preformed. There was recurrence of the pneumothorax in the next 48h.

Since the chest tube pleurodesis failed, the patient was presented to Cardiothoracic Surgery and proposed for open thoracotomy and decortication. She was rejected due to her comorbidities and frailty. So, after more then 3 months of hospital stay, with a refractory pneumothorax, the patient died due to nosocomial pneumonia.

Discussion

Pleural involvement is fairly frequent in rheumatoid arthritis3.Spontaneous and recurrent hydropneumothorax is a rare and potentially catastrophic manifestation of pleural disease. As with our patient, most have an asymptomatic presentation4. There is a firm relationship between nodular rheumatoid lung disease and spontaneous pneumothorax or pleural effusion. The phenomenon is explained by peripheral nodules, strictly close to the pleura, that can either exudate to the pleural space and create a pleural effusion or cavitate and cause pneumothorax with or without persistent fistula5.

The relationship between methotrexate and nodulosis is controversial and a review study that clearly shows this relation is yet to be done6. Nonetheless, it is postulated that a methotrexate mediated increase in adenosine levels, can be related to nodule formation7. Moreover, there are some cases that describe accelerated lung nodulosis in patients with long-lasting methotrexate treatment8 with nodule regression after drug suspension9,10,11.

In this case, the first step was to analyse the pleural fluid, which presented as a typical rheumatoid arthritis related pleural effusion, with characteristics of an inflammatory exudate, acidotic, with polymorphonuclear cells, glucose consumption and high lactate dehydrogenase levels12. Other aetiologies were excluded (malignancy, infection, tuberculosis and other connective tissue diseases).

In multidisciplinary meeting it was decided to restart methotrexate after the first discharge. Retrospectively we speculate if definitive methotrexate suspension could have avoided the hydropneumothorax recurrence. The patient was rejected for biological therapy because of the significant burden of comorbidities, which is polemic and controversial. It is known that there are no robust studies that can assure safety in treating patients with extended comorbidities13. It is also known that patients with background of important cardiovascular disease are particularly bad candidates for such treatment 14. That being said, it is worthwhile to state that this decision should be taken on a person-to-person basis.

The management of RA spontaneous hydropneumothorax is also controversial. Usually, the first strategy for rheumatoid pleural effusion is conservative. More invasive therapies like therapeutic thoracocentesis, pleurodesis and decortication may have a role in refractory cases3. The treatment of rheumatoid spontaneous pneumothorax is even more complicated. While it is reasonable that interventions like Video Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery (VATS), open thoracotomy or chemical pleurodesis should be used in recurrent pneumothorax, its use in the first episode, aiming for preventing recurrence, is highly debatable15. We decided to begin with a conservative approach, expecting that controlling the underlying disease inflammation would resolve the pleural disease. None of these objectives were achieved and we proceeded to a chest tube insertion with successful lung re-expansion. The recurrence made us change our strategy.

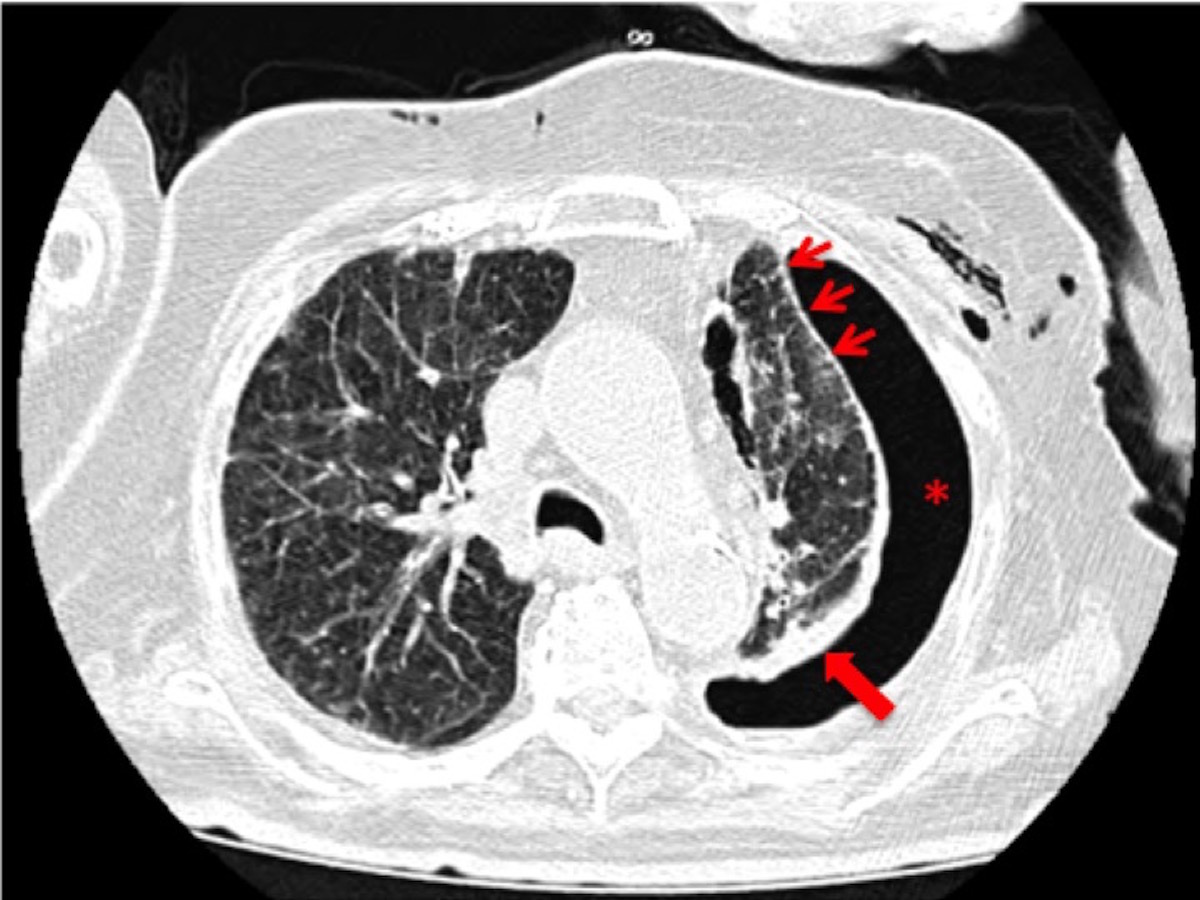

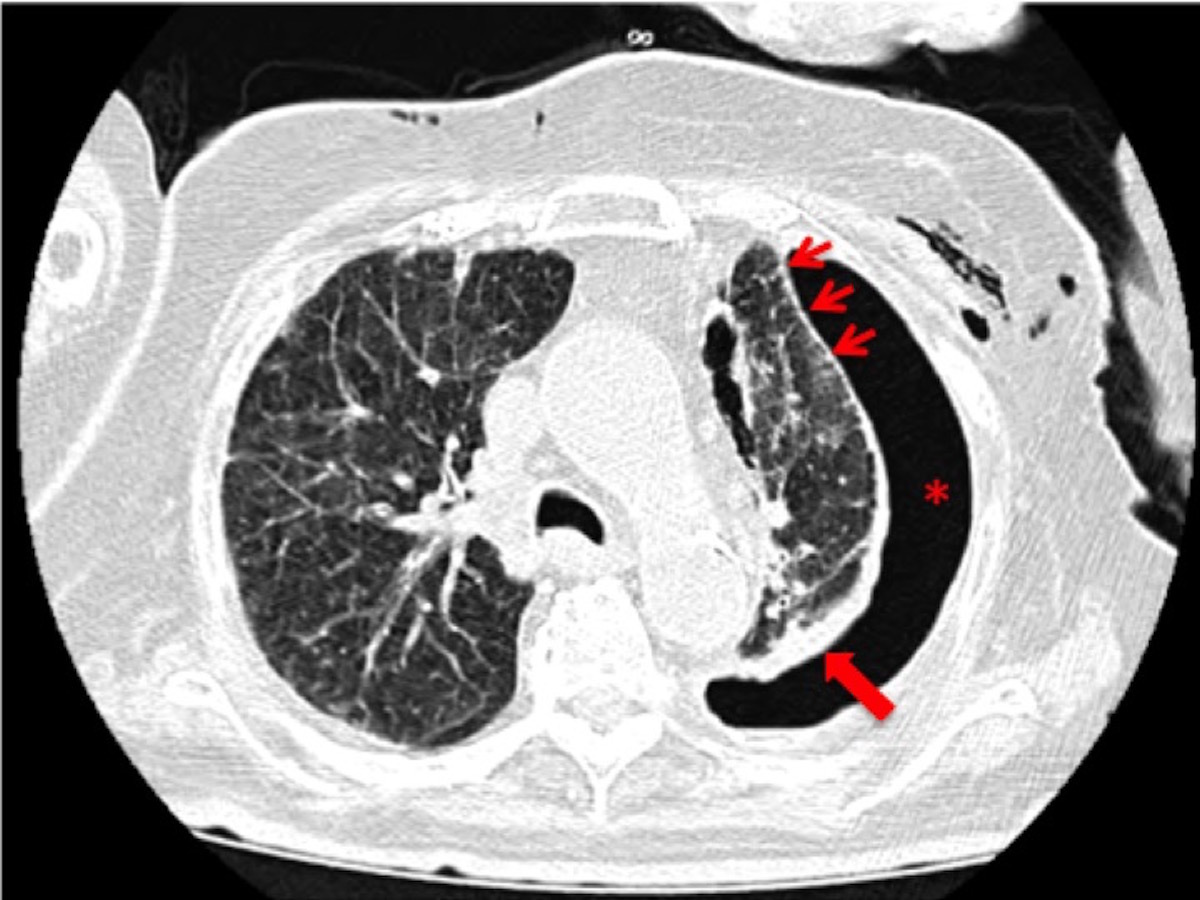

Because of the patient´s age and comorbidities in order to be less invasive we chose for chest tube talc slurry pleurodesis. After pleurodesis failure, due to the extent of adhesions and pleural thickening (figure 3.) open thoracotomy with decortication was the only valid therapeutic choice. Unfortunately, our patient was deemed unfit for surgery.

Spontaneous hydropneumothorax is a rare and challenging manifestation of RA, with scarcely defined management strategies. This case, in particular, evokes the question on whether methotrexate led to the initial hydropneumothorax and its recurrence.

Figura I

spontaneous hydropneumothorax in patient with rheumatoid arthritis with pulmonary nodulosis. Arrows: peripheral pulmonary nodules; asterisk: pneumothorax; cardinal: pleural effusion

Figura II

hydropneumothorax recurrence. Asterisk: pneumothorax chamber; cardinal: small volume pleural effusion.

Figura III

progression of disease with more peripheral pleural nodulosis (thin arrows), significant pleural thickening (thick arrow) and pneumothorax (asterisk).

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1-Lake F, Proudman S. Rheumatoid arthritis and lung disease: from mechanisms to a practical approach. Semin Respir Crit Care 2014;35(2):222-38.

2-Shaw M, Collins BF, Ho LA, Raghu G. Rheumatoid arthritis-associated lung disease. Eur Respir Rev. 2015; 24(135):1-16.

3-Balbir-Gurman A, Yigla M, Nahir AM, Braun-Moscovici Y , Rheumatoid pleural effusion. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006; 35(6):368.

4-Helmers R, Galvin J, Hunninghake GW. Pulmonary manifestations associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Chest. 1991; 100 (1): 235-238.

5-Chansakul T, Dellarioa PF, Doyle TJ, Madana R. Intra-thoracic rheumatoid arthritis: Imaging spectrum of typical findings and treatment related complications. Eur J Radiol. 2015; 84(10): 1981–1991.

6-Patatanian E, Thompson DF. A review of methotrexate-induced accelerated nodulosis. Pharmacotherapy. 2002; 22(9): 1157-62.

7-Agarwal V, Aggarwal A, Misra R. Methotrexate induced accelerated nodulosis. J Assoc Physicians India.2004; 52: 538-40.

8-Steeghs N, Huizinga TWJ, Dik H. Bilateral hydropneumothoraces in a patient with pulmonary rheumatoid nodules during treatment with methotrexate. Ann Rheum Dis 2005; 64: 1661–1662

9-Akiyama N, Toyoshima M, Kono M, Nakamura Y, Funai K, Suda T. Methotrexate-induced Accelerated Pulmonary Nodulosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015; 192(2): 252-3.

10-Alarcón GS, Koopman WJ. Nonperipheral accelerated nodulosis in a methotrexate-treated rheumatoid arthritis patient. Arthritis Rheum. 1993; 36: 132–3.

11-Falcini F, Taccetti G, Ermini M, Trapani S, Calzolari A, Franchi A, Cerinic MM. Methotrexate-associated appearance and rapid progression of rheumatoid nodules in systemic-onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1997; 40(1): 175-8.

12- Stanek KA, Mills KA. Pleural effusion with rheumatoid arthritis. S D J Med. 1991; 44(3): 61-3.

13- Richards JS, Dowell SM, Quinones ME, Kerr GS. How to use biologic agents in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have comorbid disease. BMJ. 2015; 351

14-Cacciapaglia F, Navarini L, Menna P, et al. Cardiovascular safety of anti-TNF-alpha therapies: facts and unsettled issues. Autoimmun Rev. 2011; 10: 631-5.

15- MacDuff A, Arnold A, Harvey J. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic Society pleural disease guideline . Thorax2010; 65: ii18-ii31.