Introduction

Microscopic colitis (MC) is a common cause of chronic, non-bloody diarrhoea that many times is underdiagnosed because patient’s symptoms are unspecific and the normal appearance of the colon discourages physicians from doing biopsies. MC is an umbrella term for two different entities: lymphocytic colitis (LC) and collagenous colitis (CC). MC is more common in women than men and usually affects patients in their sixth and seventh decade.1 Overall, approximately 10% to 15% of patients investigated for chronic diarrhoea are found to have this diagnosis, although this proportion is much higher in older patients.2 Chronic watery diarrhoea is the most common symptom, but patients with MC may also experience abdominal pain, faecal incontinence, weight loss and arthralgias. Colonoscopy generally reveals normal colonic mucosa but colon biopsy is the key to the diagnosis. The histopathology of LC shows a diffuse increase of intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) with >20 IELs per 100 epithelial cells, without associated thickening of the subepithelial collagen. The diagnosis of CC rest on the presence of an irregular thickening of subepithelial collagen band (> 10um), with increase of IELs.3,4 Although there are two types of MC they are approached as the same disease, since the diagnostic, treatment and follow-up are the same.(2) The pathophysiology of microscopic colitis is not well understood. Several hypotheses have been enumerated, with proposed mechanisms ranging from autoimmunity/immune dysregulation, to reaction to luminal antigen such as different medications or infectious agents.5,6

Clinical Case

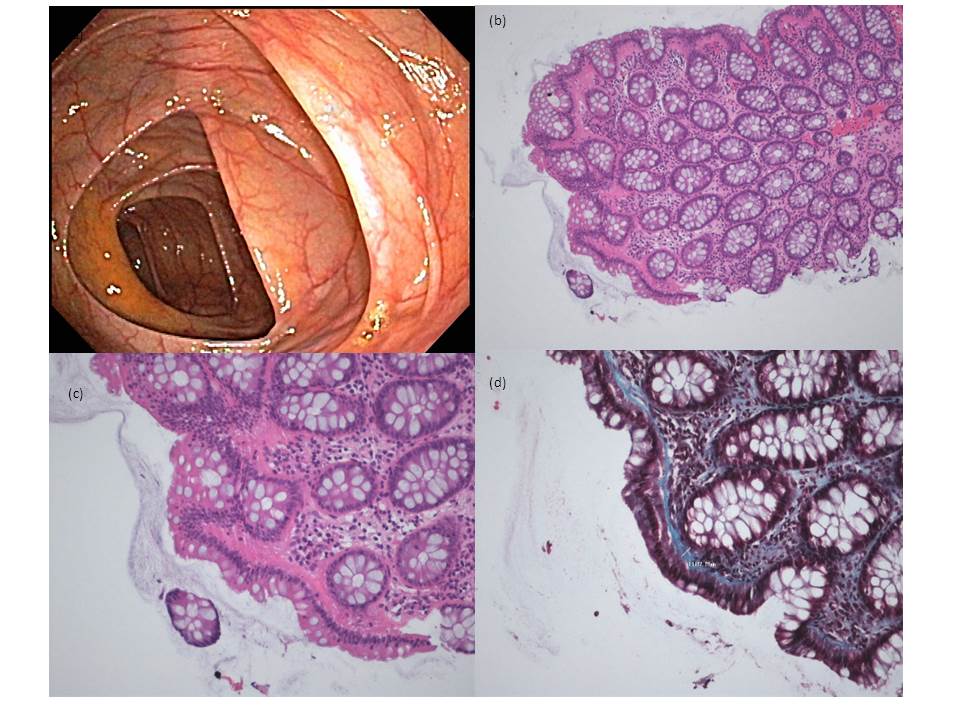

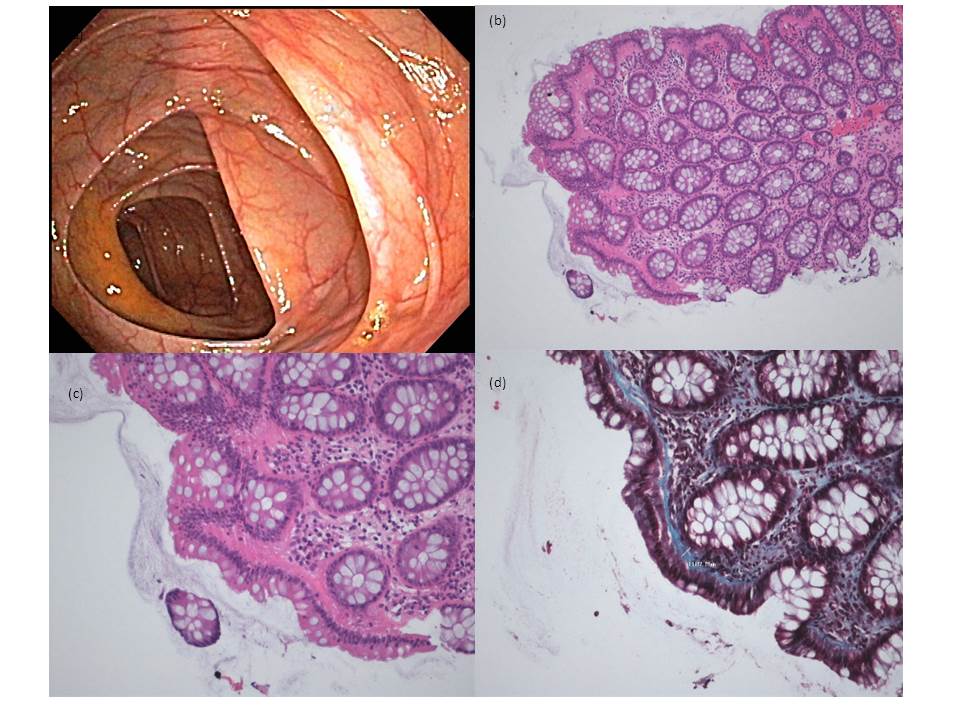

An 85 years old women with an previous medical history of dyslipidaemia, arterial hypertension and kidney stones, was chronically medicated with enalapril 20 mg plus lercanidipine 10 mg once a day, omeprazole 40 mg once a day and furosemide 40 mg once a day. She presented to the emergency department complaining about a watery diarrhoea with six months of evolution, that got worst in the last month (more than 6 dejections a day). It was associated to intense abdominal cramps, faecal incontinence and a loss of 3 kg in the last month. She had previously recurred to different physicians and received symptomatic treatment without result. The physical exam, including the rectal examination, was unremarkable. Laboratory evaluation was in the normal range of values, the abdominal X-ray also did not show any pathological finding. The patient was discharged with loperamide 2 mg three times a day, saccharomyces boulardii 250 mg once a day and dietary changes were suggested, as suspension of all milk derivatives. However, the patient returned 15 days later, maintaining the same symptoms. In order to clarify her complaints, she performed a colonoscopy that revealed no macroscopic alterations of the colonic mucosa. Biopsies were made and the microscopic evaluation identified a normal architecture of the mucosa, with an increase of lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in the lamina propria with an irregular subepithelial hyaline thickening, which in some areas was 17µm. This finding is compatible with the diagnosis of MC namely the CC subtype. Taking in account the diagnosis and the exuberance of symptoms she started budesonide 9 mg once a day and stopped omeprazole. The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflamatory drugs (NSAID´s) was forbidden. Other pathologies that are associated to MC as celiac disease, autoimmune pathology, infectious colitis were excluded. After 2 weeks of treatment with budesonide the patient noticed a complete resolution of the watery diarrhoea and abdominal cramps, budesonide was discontinued after 2 two months. A week after stopping budesonide, symptoms recurred so another cycle of budesonide 9 mg once a day during 2 weeks followed by a gradual tampering over the next 6 months was started. This regimen was stopped 4 months ago and the patient never had another episode of watery diarrhoea and regained her normal weigh.

Discussion

MC is a common cause of chronic diarrhoea, but its diagnosis is difficult because the symptoms are highly uncharacteristic and the normal appearance of the colonic mucosa may discourage the realization of biopsies. Our patient had symptoms for the last 6 months, had consulted different doctors and done a colonoscopy, but as there were no macroscopic changes and the blood analysis were unremarkable, the conservative approach was the first choice, leading to the delay of the diagnosis.

This case in particular, highlights some challenges that comes with the disease, we don’t have a well-established pathophysiologic mechanism. There are many possible disease triggers involved: drug’s, infections, bile acids, genetic susceptibility, abnormal collagen metabolism. So, a careful medical history should be executed, with special attention to chronic medication specially NSAID’s, proton pump inhibitors, histamine-2 receptor blockers, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors,carbamazepine and simvastatin.2 On the other hand, it’s important to schedule a dietary consultation, to educate the patient in his diet. Elderly patients should be encouraged to remove all milk derivatives from the diet, because this population has an elevated rate of lactose intolerance and it can be interpreted as treatment failure.

The mild cases can normally be managed withdrawing the offending agents in association with symptomatic treatment, as loperamide. For more severe cases or the ones who do not respond to initial therapy oral budesonide is the best treatment option with a response rate reaching 90 %.7 The problem, as with our patient, is the elevated rate of recurrence that can reach values of 61% in some studies 8. There isn’t a consensus on how to the approach this complication, most authors suggest a gradual tampering of the corticoid in a time window between six to twelve months.When the patient does not tolerate the suspension of the corticoid, other drugs like azathioprine, methotrexate, or anti-tumour necrosis factor therapies can be used.

Conclusion

MC is a common cause of chronic diarrhoea in the elderly, but at the same time MC is a poorly explored disease in the actual literature and its symptoms are interspecific, so a high level of suspicion is necessary to think of its possibility, allowing an early diagnosis and improvement of the patient’s quality of life. Oral budesonide is the only approved treatment, but although highly effective, the rate of recurrence of symptoms is high and there is no consensus on how to approach this group of patients.

Figura I

The colonoscopy and the histological features of the mucosa were the key to the diagnosis. (a)- colonoscopy showing a normal colon mucosa; (b)- colonic mucosa with preservation of normal gland architecture and discrete increase of inflammatory lymphocytic infiltrate in the chorion (hematoxylin and eosin, 100x); (c) - Subepithelial hyaline thickening and slight increase of intraepithelial lymphocytes (hematoxylin and eosin, 200x); (d)- The coloration of trichrome underlines the subepithelial hyaline thickening (Gomori, 200x)

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Park T, Cave D, Marshall C. Microscopic colitis: A review of etiology, treatment andrefractory disease. World J Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2015 Aug 7 [cited 2018 Aug24];21(29):8804.

2. Pardi DS. Microscopic colitis. Clin Geriatr Med [Internet]. 2014 Feb 1 [cited 2018 Aug24];30(1):55–65.

3. Farrukh A, Mayberry JF. Microscopic colitis: a review. Color Dis [Internet]. 2014 Dec[cited 2018 Aug 24];16(12):957–64.

4. Münch A, Langner C. Microscopic Colitis: Clinical and Pathologic Perspectives. ClinGastroenterol Hepatol [Internet]. 2015 Feb [cited 2018 Aug 24];13(2):228–36.

5. Goff JS, Barnett JL, Pelke T, Appelman HD. Collagenous colitis: histopathology andclinical course. Am J Gastroenterol [Internet]. 1997 Jan [cited 2018 Aug24];92(1):57–60.

6. Kingham JG. Microscopic colitis. Gut [Internet]. 1991 Mar [cited 2018 Aug24];32(3):234–5.

7. Miehlke S, Heymer P, Bethke B, Bästlein E, Meier E, Bartram H-P, et al. Budesonidetreatment for collagenous colitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled,multicenter trial. Gastroenterology [Internet]. 2002 Oct [cited 2018 Aug26];123(4):978–84.

8.O’Toole A. Optimal management of collagenous colitis: a review. Clin Exp Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Mar 30];9:31–9