Introduction

The majority of patients who visit the emergency department presenting with acute chest pain have non-life-threatening etiologies. Nevertheless, catastrophic causes of chest pain must be considered while performing the differential diagnosis. Among them, esophageal perforation is a serious injury of the digestive tract.

Case description

A 77-year-old caucasian man was admitted in the intermediate care unit with a 4-day history of dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, fever and dyspepsia.

He had a history of valvular heart disease (with an aortic biological valve prosthesis), atrial fibrillation, essential hypertension, dyslipidemia and asthma.

He had previously been evaluated in the emergency department 2 days after the onset of the symptoms. An upper respiratory viral infection was diagnosed, and he was discharged with symptomatic therapy. Due to the persistence of the symptomatology, aggravated with fever, he returned to the emergency department. Upon physical examination, the patient had a pulse of 105 beats per minute, blood pressure 98/58 mmHg, SpO2 93 % on air and an auricular temperature of 39,5° C. Pulmonary auscultation evidenced stertors on the right lung base. Abdominal palpation revealed a pain located on the right hypochondrium and epigastrium that worsened with decompression. His laboratory results showed a raised white blood cell count (17,8 × 103/mL with neutrophilia; reference range: 4 – 11 × 103/mL), thrombocytopenia (platelets 126x103/ml; reference range: 130 – 450 × 103/mL), an elevated creatinine concentration (1,53 mg/dL; reference range: 0,4 – 1,2 mg/dL) and an increased C-reactive protein concentration (41,36 g/dL; reference range: 0,02–0,75mg/dL). Other measurements were found within the expected ranges. Arterial blood gas analysis in room air revealed pH 7,53, paCO230 mmHg, paO2 59 mmHg, HCO3- 25,1 mmol/L, lactate 1,7 mmol/L; Sat.O2 93%. The chest X-ray showed opacity in the right lung base (Figure 1) and the search for both pneumococcal and legionella urine antigens was negative. An abdominal ultrasound was performed and evidenced hepatomegaly. At this point the patient presented clinical and analytical criteria for the diagnosis of sepsis with a starting point in a community-acquired pneumonia with multiple organ failure (respiratory and renal). Samples were collected for blood cultures, ceftriaxone and azithromycin were empirically initiated and the patient was admitted in the intermediate care unit. After 24 hours of treatment, given the persistence of fever and the worsening of the respiratory symptoms, a thoraco-abdominal computed tomography scan was performed. The exam revealed signs suggestive of pneumomediastinum below the level of the carina, with poor definition of the esophagus at this level, a densification in the right base of a probable inflammatory nature and a bilateral pleural effusion (Figures 2 and 3). After reviewing the clinical history, the patient reported that it had all started after swallowing a small chicken bone and choking on it, being left with the feeling of a bloated stomach. Since then, he had had an aggravation of epigastric discomfort and, progressively, the installation of respiratory symptoms. An endoscopic assessment revealed esophageal perforation, which was closed with clips. An esophageal transit and computed tomography scan with oral contrast was made, which did not reveal leakage and showed favorable imaging evolution. The patient completed 20 days of empiric antibiotherapy with piperacillin tazobactam, which was changed to vancomycin after the identification of Staphylococcus epidermidis in the blood cultures. He was discharged 40 days after admission with a complete symptom resolution.

Discussion

Esophageal perforation has been regarded as the most serious injury of the digestive tract1.The majority of ingested foreign bodies that enter the esophagus pass through the gastrointestinal tract, but 7 to 14 % are responsible for esophageal perforations1,2. The diagnosis of foreign bodies is based on the patient’s diet history and symptoms (foreign bodies sensation, sore throat, dysphagia, odynophagia, retrosternal pain, retching and vomiting)2,3. Clinical manifestations may be seen immediately or up to 2 weeks afterwards, as a gradual erosion of the impacted foreign body through the esophageal wall1. The sensation of foreign bodies and localized pain could be the main complaints in the early period, but later localized or systemic symptoms may become evident2. With this patient, the non-association of a possible esophageal perforation with the symptoms of dyspnea, dyspepsia and pleuritic chest pain led to the development of sepsis with multiple organic dysfunction. Due to an erroneous belief that a pulmonary complication was the cause of this specific clinical picture, the diagnosis of esophageal perforation was not suspected. The original diagnosis of esophageal perforation was delayed because of misinterpretation of right pleural effusion as a basal pulmonary pathology. Computed tomography scans have become very useful in the diagnosis of esophageal perforation1. They can detect esophageal perforation (signs of esophageal thickening or extraluminal gas or contrast medium), and furthermore mediastinitis secondary to esophageal perforation (signs of increased attenuation of mediastinal fat, localized mediastinal fluid collections, pericardial or pleural effusions, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy)1. The treatment depends on the etiology, site, and size of the perforation; the elapsed time between perforation and diagnosis; a possible underlying esophageal disease; and the overall health status of the patient1. Treatment should be started as soon as possible and should avoid oral administration and include intravenous fluid, broad spectrum antibiotics, narcotic analgesics, total parenteral nutrition and a decision regarding surgical closure versus non operative management3,4,5. Perforation of the cervical esophagus can be conservatively managed in most cases3,4,5. Perforations of the lower two thirds of the esophagus that affect the pleura, the pericardium or the peritoneum require rapid surgical intervention1,5. An esophageal repair should be made if the condition is presented earlier, or an esophageal diversion, if the presented later1,5. Several independent predictors have been associated to an increased risk of mortality in patients with esophageal perforation such as age, coronary artery disease and esophageal malignancy6. An early diagnosis and an aggressive treatment are the most important prognostic factors4. The reported mortality from treated esophageal perforation is 10 to 25 %, when therapy is initiated within 24 hours of the perforation but could rise to 40 to 60 % when the treatment is delayed beyond 48 hours7.

Figura I

Chest X-ray showed an opacity in the right lung base

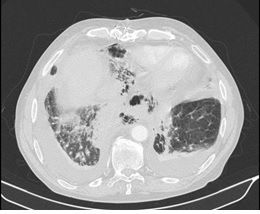

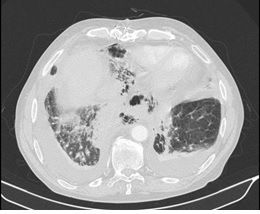

Figura II

Computer tomography scans showing pneumomediastinum below the level of carina, with poor definition of the esophagus at this level, densification in the right base and bilateral pleural effusion.

Figura III

Computer tomography scans showing pneumomediastinum below the level of carina, with poor definition of the esophagus at this level, densification in the right base and bilateral pleural effusion.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1 – Tsalis K, Blouhos K, Kapetanos D, Kontakiotis T et al. Conservative management for an esophageal perforation in a patient presented with delayed diagnosis: a case report review of the literature. Case Journal 2009; 2:6784

2 – Kim H. Oroesophageal Fish Bone Foreign Body. Clinical Endoscopy 2016; 49:318-326

3 – Cross M, Greenwald M, Dahhan A. Esophageal Perforation and Acute Bacterial Mediastinitis: Other Causes of Chest Pain That Can Be Easily Missed. Medicine 94(32):e1232

4 – Berry A, Draganov P, Patel B, Avalos D, Reuther WL, et al. Embedded Pork Bone Causing Esophageal Perforation and an Esophagus-Innominate Artery Fistula. Case Reports in Gastrointestinal Medicine 2014; Article ID 969862

5 – Lázár G, Paszt A, Mán E. Role of endoscopic clipping in the treatment of oesophageal perforations. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 8: 13–22

6 – Leo M, Maselli R, Ferrara E, Poliani L, Alwadhi S, et al. Endoscopic Management of Benign Esophageal Ruptures and Leaks. Curr Treat Options Gastro 2017; 15:268–284

7 – Kaman L, Iqbal J, Kundil B, Kochhar R. Management of Esophageal Perforations in Adult. Gastroenterology Res 2010 Dec; 3(6): 235–244.