Introduction

The most common cause of duodenal villous atrophy is coeliac disease. However, other causes must be considered when serologic markers for coeliac disease are negative. Such examples are autoimmune or infectious enteropathies, in addition to olmesartan-induced enteropathy [1].

We present the case of a patient with severe chronic diarrhea complicated with acute renal failure and severe hypokalemia caused by olmesartan use.

Case Report

This case concerns an 82-year-old man, previously independent in activities of daily living, with known history of arterial hypertension and dyslipidaemia, treated with the combination of olmesartan 20mg with hydrochlorothiazide 12.5mg for 5 years, diltiazem 200mg and pravastatine 40mg.

He was admitted to the emergency department after syncope, without head trauma. He reported a history of diarrhea, with 2 or 3 loose bowel movements per day for the previous 2 months, without blood, mucous or pus. Additionally, he mentioned progressive fatigue and non-quantified weight-loss. There was no history of fever, abdominal pain, nausea or vomiting. He was medicated with Saccharomyces boulardii and cefixime, with no improvement.

Physical examination showed signs of dehydration with no other remarkable findings. Laboratory results revealed severe hypokalemia (K 1.82 mmol/L), mild hypomagnesemia (Mg 1.5 mg/dL) and acute renal failure (serum creatinine 2.35 mg/dL and urea 130 mg/dL), with normal values of other blood minerals, complete blood count and C-reactive protein. Electrocardiogram revealed sinus rhythm without changes justifying the syncope. He had an outpatient colonoscopy with no macroscopic abnormalities of colonic mucosa, but biopsies were not done.

The diagnosis of severe dehydration (with acute renal failure and severe hypokalemia) leading to syncope was admitted, caused by chronic diarrhea, etiology to be determined.

Clostridium difficile toxin, parasitological and cultural stool tests for Campylobacter, Salmonella and Shigella were negative. Thyroid function was normal and human immunodeficiency virus serology was negative. He presented hypoalbuminemia of 2.80 g/dL, folic acid of 5.68 ng/mL and vitamin B12 of 182 ng/mL. Both IgA and IgG anti-transglutaminase antibodies were negative.

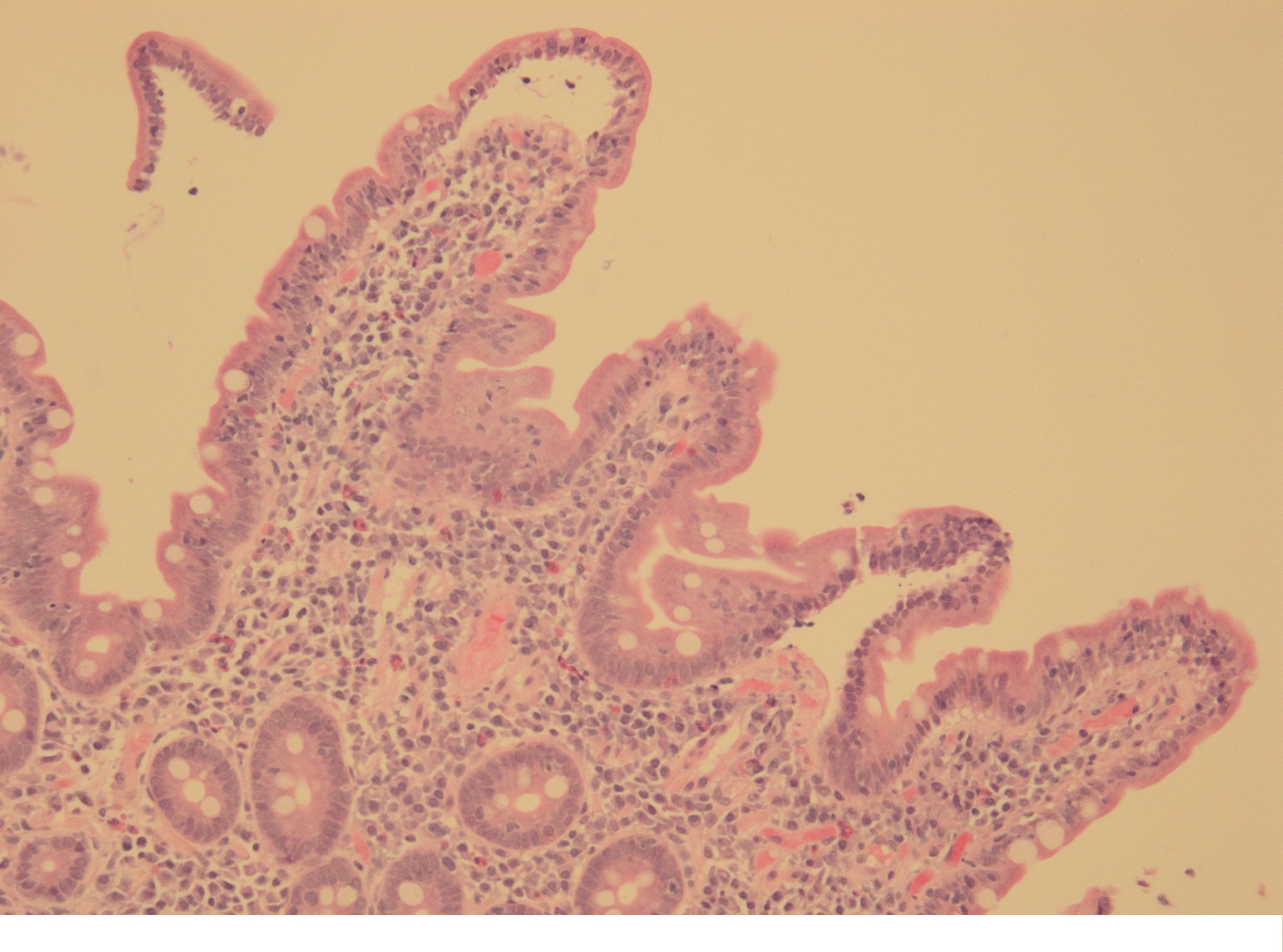

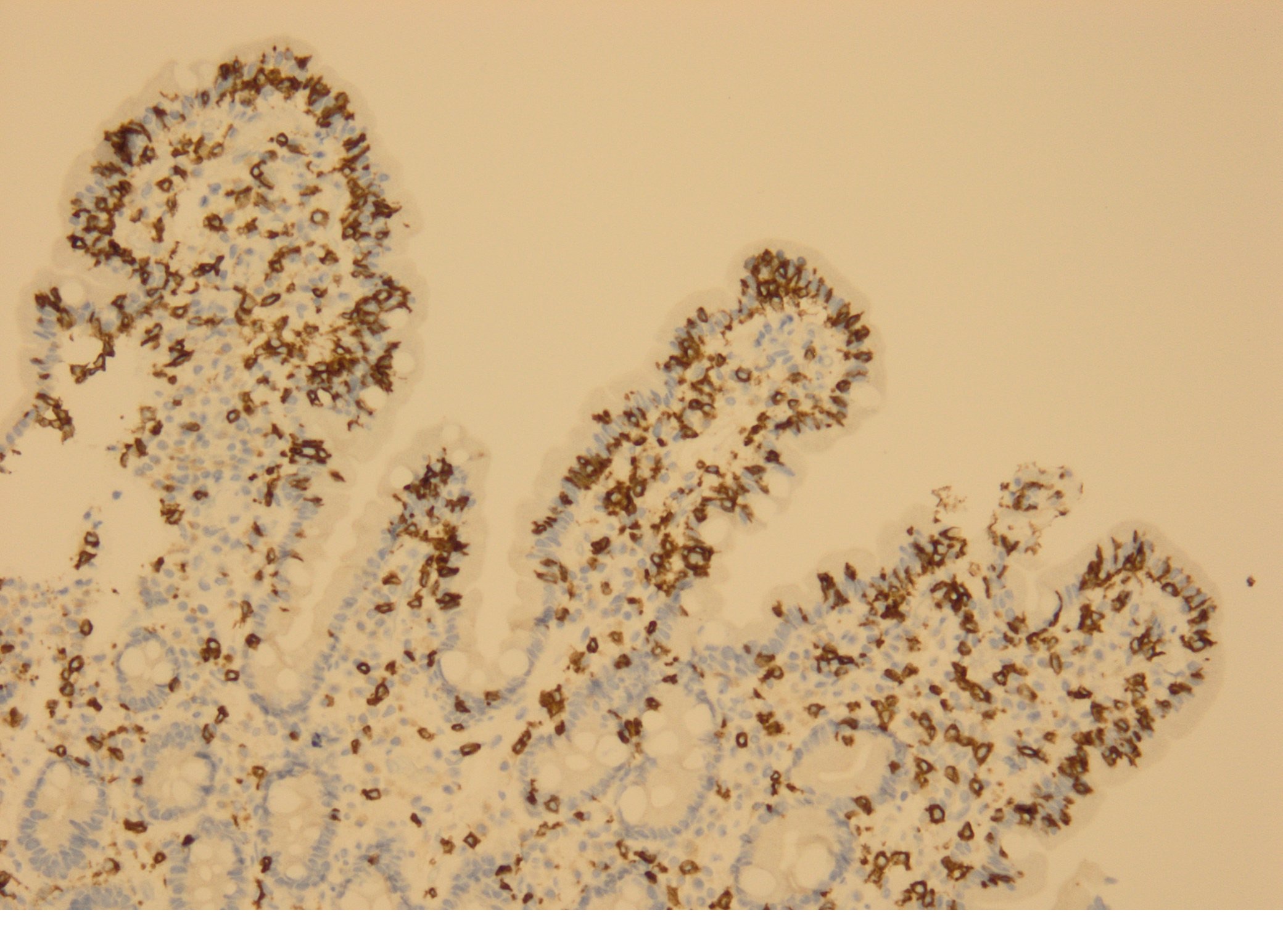

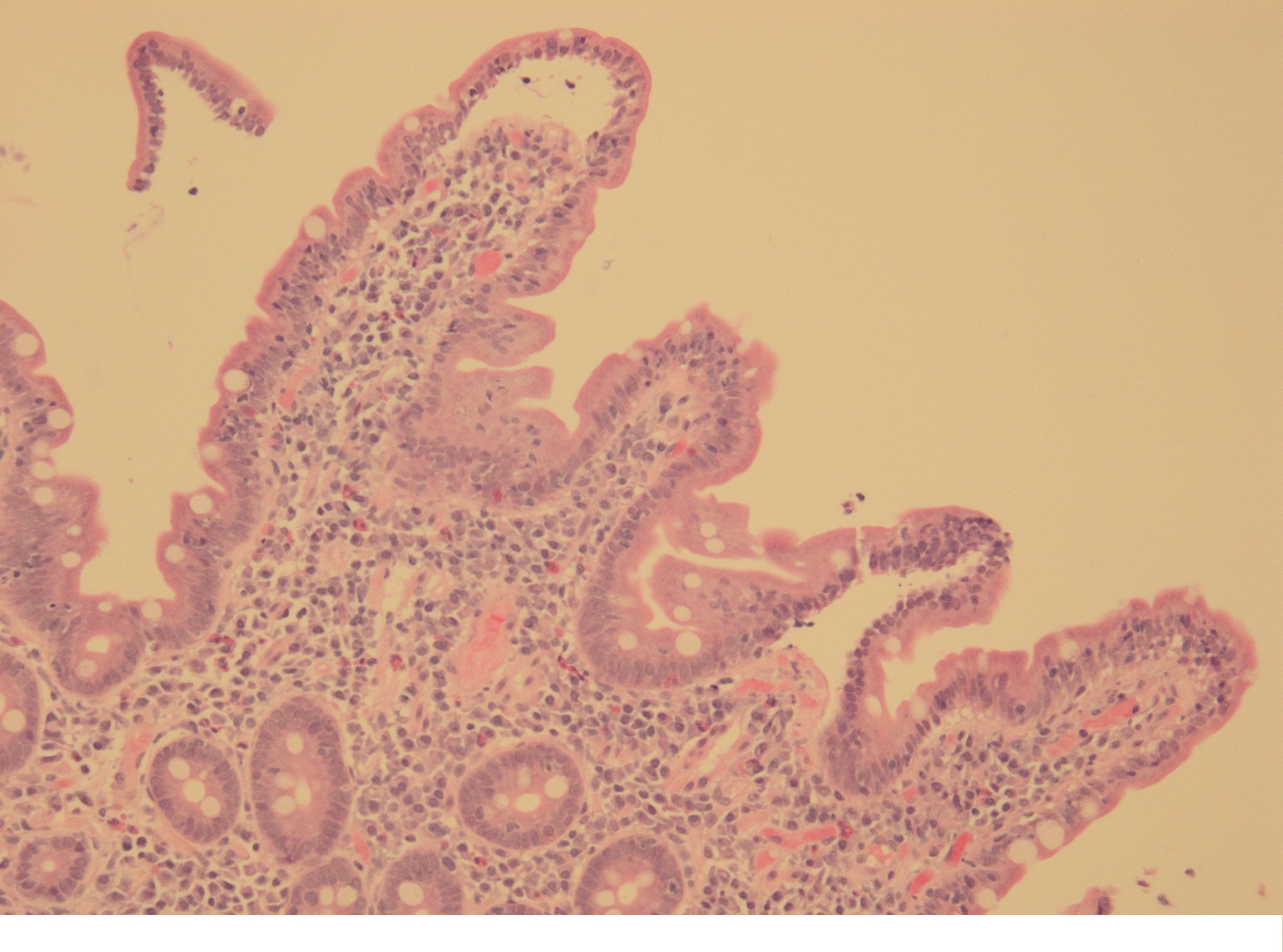

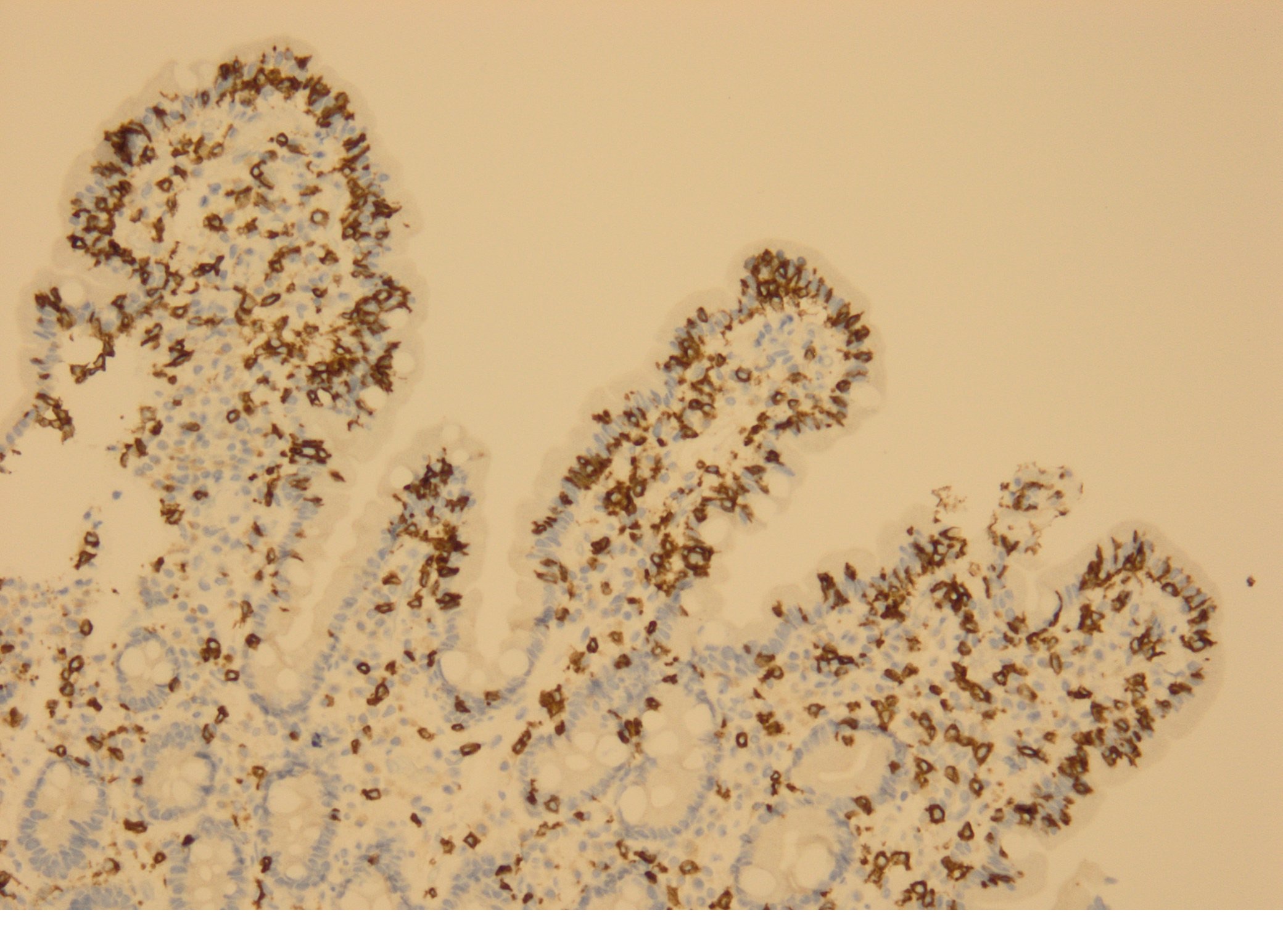

There were no macroscopic findings at upper endoscopy, but duodenal biopsies revealed lymphoplasmocytic inflammatory infiltration in the lamina propria with some eosinophils, villous atrophy and increased number of intraepithelial lymphocytes (Figures 1 and 2). No microorganisms were found.

The patient´s condition promptly improved with fluid and electrolyte replacement. Five days after admission, diarrhea stopped and renal function and kalemia normalized. In addition to hydrochlorothiazide and diltiazem, lisinopril 20mg was started, with blood pressure control and no side effects reported.

Towards a complete symptom’s resolution 5 days after antihypertensive drugs withdrawal, with serologic exclusion of coeliac disease, an olmesartan-induced enteropathy was admitted. However, after symptom resolution and histologic confirmation of enteropathy, when applying the adverse drug reaction (ADR) score [2], we obtained 3 points, which means that there is only a possible association between olmesartan and diarrhea.

One year after olmesartan withdrawal, the patient remains asymptomatic, without new episodes of diarrhea.

Discussion

Diarrhea’s definition and its classification as acute or chronic may vary, but a pragmatic definition might be an increased number in frequency and/or decrease in stool consistency for a period longer than 4 weeks. The estimated prevalence of chronic diarrhea without abdominal pain in the occident is 4-5% [3].

Up to 4% of chronic diarrheas are due to medications. Drugs more often associated with chronic diarrhea are those containing magnesium, diuretics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), anti-neoplastic agents, oral anti-diabetes drugs and antiarrhythmics [3]. NSAIDs can lead not only to small bowel lesions, but also to chronic colitis that may range from unspecific microscopic findings to significant ulcerations [4]. Besides NSAIDs, other drugs related to microscopic colitis with chronic diarrhea are proton-pump inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and statins [5]. For this diagnosis, a total colonoscopy with biopsies from the different colon segments is needed, since some of these drugs affect predominantly the right colon [4,5].

Olmesartan has been associated with an enteropathy similar to sprue, and might occur months to years after starting this drug. The most common manifestation is chronic and painless diarrhea, which might lead to renal impairment and/or malabsorption of vitamins and ions. These abnormalities arise from small bowel villous atrophy, together with an increase in intraepithelial lymphocyte number [1,6].

The pathogenesis of olmesartan-induced enteropathy is still unknown, but it is believed it has an autoimmune source [6]. Chronic use of olmesartan has been associated with an increased number of intraepithelial lymphocytes not only in the small bowel, but also on the stomach and colon, suggesting this drug might affect the whole gastrointestinal tract. Although the association of enteropathy with other angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ARAs) has been reported, plausible explanations for its larger association with olmesartan might be its conversion into the active form in the intestine, its longer half-life and higher efficacy compared to other ARAs. Epithelial recovery occurs promptly after drug discontinuation [1].

In this case, there was a substantial improvement in both patient clinical status and laboratory abnormalities, whereby a second colonoscopy with biopsies to exclude microscopic colitis was not performed. Taking into account the patient’s age and complete symptom’s resolution, we did not perform an upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsy to confirm the epithelial recovery.

In conclusion, this report aims to alert clinicians to this increasingly diagnosed aetiology of chronic diarrhea. Because olmesartan can cause symptoms years after it was started, we should always consider this drug as a possible cause of chronic diarrhea.

Figura I

Duodenal mucosa with mild villous atrophy, villi enlargement due to a chronic lymphoplasmocitic infiltration with some eosinophils, accompanied by an increased number of intraepithelial lymphocytes at the villi epithelium (HE stain, 10x)

Figura II

Immunohistochemical staining for CD3 (a lymphocyte T marker), revealing an increased number of intraepithelial lymphocytes at the villi epithelium (Immunohistochemical staining with CD3, 10x)

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Eusébio M, Caldeira P, Antunes AG, Ramos A, Velasco F, Cadillá J, et al. Olmesartan-Induced Enteropathy: An Unusual Cause of Villous Atrophy. GE Port Gastroenterol. 2016; 23: 91-95. doi: 10.1016/j.jpge.2015.09.005

2. Arasaradnam RP, Brown S, Forbes A, Fox MR, Hungin P, Kelman L, et al. Guidelines for the investigation of chronic diarrhoea in adults: British Society of Gastroenterology, 3rd edition. Gut. 2018; 0:1–20. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315909

3. Seminerio J, McGrath K, Arnold CA, Voltaggio L, Singhi AD. Medication-associated lesions of the GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014; 79: 140-150. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.08.027

4. Tong J, Zheng Q, Zhang C, Lo R, Shen J, Ran Z. Incidence, Prevalence, and Temporal Trends of Microscopic Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015; 110:265–276. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.431

5. Melis C, Struyve M, Steelandt T, Neuville B, Deraedt K. Sprue-like enteropathy, do not forget olmesartan! Digestive and Liver Disease. 2018; 50: 621-632. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2018.03.017