Mediastinal Masses can be caused by many benign or malignant conditions and can originate from anywhere in the mediastinum or pass through it or merely be a presentation of metastatic disease of a malignancy from elsewhere in the body. These masses are most commonly an incidental finding on an imaging exam or diagnosed due to symptoms from direct mass effect and compression or systemic effects of the illness such as paraneoplastic syndromes.1

Hodgkin´s lymphoma and mediastinal large cells Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas are the most frequent causes of mediastinal masses in patients under 40 years old. These conditions are normally associated with “B” symptoms as well as other symptoms of lymphoma such as anaemia.

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma is an uncommon mature B cell lymphoma usually involving bone marrow and, less commonly, spleen and/or lymph nodes. It is frequently associated with Waldenström’s2and constitutes around 1% of all hematologic malignancies in the US and Western Europe (incidence of approximately 8.3 cases per million persons per year2) The vast majority of patients are Caucasian with other ethnic groups accounting for approximately 5% of all cases. The median age at diagnosis is 65 years and 50 to 60 percent of patients are male. The diagnosis is made by the presence of small lymphocytes, plasmacytoid lymphocytes, and plasma cells, with variable numbers of admixed immunoblasts in a biopsy with the expression of a typical immunophenotype with the MYD88 mutation being present in most.

Case presentation

A 38 year old African Woman born and living in Angola without any known previous medical condition was transferred to a Portuguese hospital due to productive cough, dyspnoea, thoracalgia, overt asthenia and oedema of the face and neck over a 5 month period. The patient reported generalised cutaneous pruritus, which worsened at night and with hot baths, weight loss of over 10 kg in 3-4 months, anorexia without gastrointestinal discomfort. She reported no history of nocturnal diaphoresis, no palpable adenopathy in the neck or inguinal area as well as no fever. A previous analytical evaluation from Angola showed anaemia with 7,9 g/dL of haemoglobin, a C-reactive protein of 36.6 mg/L, a normal leucogram, erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 42 mm/h, and uric-acid of 7 mg/dl with no liver function or renal function abnormalities.

On admission the patient appeared tired, with signs of weight loss, afebrile, blood pressure 137/77 mmHg, the pulse was 104 beats per minute, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute and the oxygen saturation 94-95% breathing ambient air. Her right jugular vein was distended with swelling of the face, neck and arms on the right side. Pulmonary auscultation showed decreased breath sounds in the lower half of the right hemithorax and in this area percussion also revealed dullness. The abdominal examination revealed hepatomegaly with a soft liver that was palpable 4 centimetres below the right costal margin with an enlarged palpable spleen 2 centimetres below the left costal margin. No peripheral adenopathy was identified and the remainder physical examination was unremarkable.

Immediate serology for HIV type 1 and 2 was negative (ELISA Essay), Hepatitis B and C were negative as well as Treponema Pallidum antibody. Epstein - Barr virus viral load and Human Herpes Virus-8 were also negative and no immunoglobulin peaks were found on electrophoresis with a Beta 2- microglobulin of 2.13mg/l.

Transthoracic Echocardiography showed an echogenic mass in the right heart with an enlarged inferior Vena Cava but without evidence of thrombus inside the vessel. A caudal dislodgement of the heart by a mass without defined borders in the location of the large vessels was seen as well as a small pericardial effusion larger at the right ventricle.

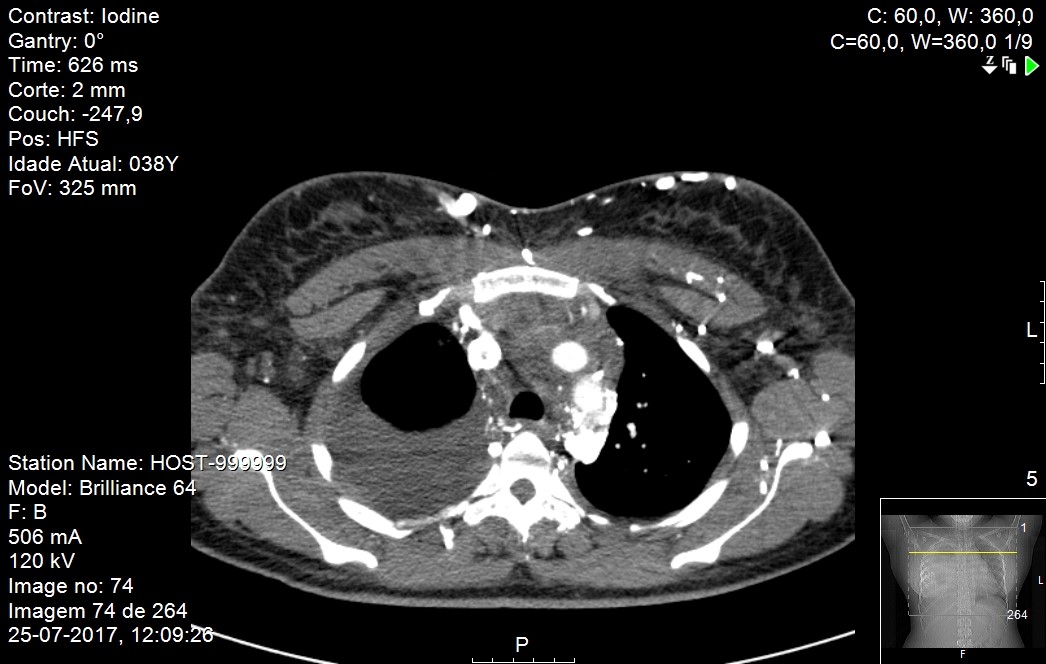

A CT scan of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis showed an anterior mediastinal mass, lateralized to the right, with apparent epicentre above the cardiac area, causing a contralateral deviation of the mediastinum. The mass was lobulated with ill-defined borders measuring 12x10x12 cm with a lower density centre which was suggestive of necrosis. Invasion of the right atrium with extension to the right ventricle through the tricuspid valve was also observed invading also the interatrial septum while incarcerating the right pulmonary artery. The superior vena cava was also enveloped causing obstruction with thrombosis of both troncular brachiocephalic veins, the right and left subclavian veins and the internal right jugular vein, with exuberant collateral venous circulation.

The bone marrow aspirate had no remarkable abnormalities but no genetic analysis was performed or immunophenotyping and a biopsy of the mass was performed by thoracotomy which the preliminary biopsy report suggested a non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma. As such the patient was transferred to a Haematology ward where she started R-CHOP

(Figure 1). An initial CT scan of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis showed an expansive solid ill-defined mass (9.3x8.4x11.0 cm) of the mediastinum invading the right heart and vascular structures.

The final biopsy report described a dense and diffuse proliferation of small lymphoid cells, with round nucleus filled with clumped chromatin with some larger cells with obvious nucleolus with loose clumps. Residual dendritic follicular cells were found by CD21 marker with a proliferative index around 40%. The immunohistochemistry of the neoplastic cells showed immunoreactivity to CD20, CD23, CD43 and in a smaller number to bcl-2 and CD10 (weak and focal staining), those cells were negative to CD5, cyclin D1, CD21, CD138 and bcl-6.The biopsy material was then sent for molecular assessment to search for the MyD88 marker or translocation t(11,18) but both were negative.

The pathological examination conclusion was that the mass was a Non-Hodgkin B Lymphoma of small cells with lymphoplasmacytic differentiation which could be a Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma, an extraganglionic Marginal Zone Lymphoma or Lymphocytic Lymphoma and required further material for a more definite diagnosis.

After the final pathological results and completing the first cycle of R-CHOP the patient was discharged to ambulatory treatment in day-hospital where she completed 8 cycles R7CHOP8.

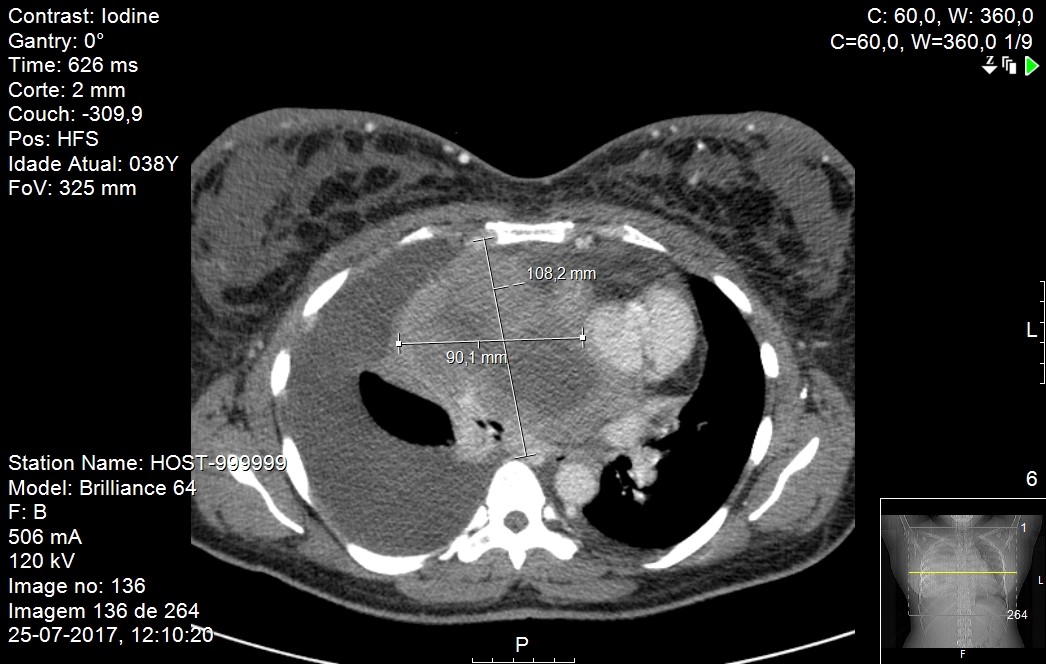

A repeat CT scan of the neck, thorax, abdomen and pelvis after the 8 cycles showed a significant reduction of volume with the mass now measuring 8 x 6.5 x 8.5 cm with central necrosis and still invading the right atrium, although less expressive and with no extension to the right ventricle but still involving the thoracic vascular structures.Figures 2. After this exam the patient returned to her home country with the final diagnosis of LPL, stage IIE with partial response to treatment and follow up was lost.

Discussion

Malignant lymphomas account for nearly 20% of all mediastinum neoplasms in adults. These are mostly diffuse large B cell.(2)This seemed to be the most probable diagnosis due to the clinical symptoms of the patient, infiltrative characteristics of the mass, age and gender of the patient, presence of superior vena cava syndrome and the alterations in the blood count with an elevated LDH. Another factor was the absence of any signs of metastasis or any other ganglionic involvement common in this types of lymphoma.3,4 However a bone marrow biopsy or PET scan where not performed searching for bone marrow involvement.

The final biopsy report showed a pattern of a Non-Hodgkin B Lymphoma of small cells with lymphoplasmacytic differentiation (which could either be Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma, Extranodal Marginal Zone Lymphoma or Lymphocytic Lymphoma). Extranodal Marginal Zone Lymphomas can occur outside lymph nodes (e.g., in the gastrointestinal tract, thyroid, orbit, leptomeninges, spinal cord, or skin) and normally are predisposed to spread to other regions within the aerodigestive tract and not to the mediastinum. Also in those lymphomas the translocation t(11;18)(q21;q21) API2-MALT1 is found in around 30% of lymphomas while its absence does not exclude the diagnosis it does make it less likely. In this caseLymphocytic Lymphoma is a diagnosis of exclusion as, although it does not show some of thehallmark characteristics, the behaviourand microscopical aspect of the tumour are sugestive; Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma (SLL) represents a different manifestation of the same disease as Chronic Lymphocytic Lymphoma (CLL), an indolent and prevalent disease. The major difference is that in CLL, a significant number of the abnormal lymphocytes are also found in the bone marrow and blood, while in SLL the abnormal lymphocytes are predominantly found in the lymph nodes and bone marrow.5,6

Although the search for MyD88 and t(11,18) was negative and despite those being considered one of the main markers for this type of lymphoma the authors believe this case to be a rare presentation of a Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma that has been previously documented in Raufi et al. but is extremely rare and still not fully studied as the rarity of this diagnosis makes large studies difficult.3 The absence of other markers for the indisputable diagnosis of other mature B-cell lymphomas reinforces the authors and the hematologists believe on the lymphoplasmocitic lymphoma diagnosis.

Accurate diagnosis of LPL/WMand differentiation from other small B-cell lymphomas is challenging due to the absence of specific morphologic, immunophenotypic or chromosomal markers. It would have helped if further material could have been collected and further studies performed. However, the urgency of initiating treatment made delaying diagnosis impossible.2

Rare cases of LPL that present primarily with extramedullary disease and are not WM remain poorly characterized, likely related to the reproducibility of the diagnosis being highest only in the setting of IgM gammopathy with bone marrow involvement. Conversely, diagnosis of extramedullary LPL lacks sufficient criteria for adequate reproducibility and is frequently indistinguishable from cases of small B-cell lymphoma with plasmacytic differentiation7. These cases are frequently diagnosed based on clinical experience and patient evolution as this one8. But as a mature B-cell lymphoma this presentation of isolated bulky disease seems unusual enough to be reported per se.

Like many other mature, small B-cell lymphomas, LPL is an indolent, incurable disease with a median survival of 5 to 10 years after diagnosis.2,8 In this patient with this rare presentation with local invasion of the heart and major vessels the prognosis is very poor.

Figura I

Pleural effusion and vena cava compression

Figura II

Mass dimensions

BIBLIOGRAFIA

[1]. Juanpere S, Cañete N, Ortuño P, Martínez S, Sanchez G, Bernado L. A diagnostic approach to the mediastinal masses. Insights into Imaging. 2013;4(1):29-52. doi:10.1007/s13244-012-0201-0.

[2]. Nadia Naderi, David T. Yang, (2013) Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma and Waldenström Macroglobulinemia. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine: April 2013, Vol. 137, No. 4, pp. 580-5.

[3]. Raufi A, Jerkins J, Lyou Y, Jeyakumar D. A Patient with Supraclavicular Lymphadenopathy and Anterior Mediastinal Mass Presenting as a Rare Case of Composite Lymphoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. Case Reports in Oncology. 2016;9(3):854-860. doi:10.1159/000453255

[4]. Zelenetz AD, Gordon LI, Wierda WG, et al. Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma, Version 1.2015: Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2015;13(3):326-62.

[5]. Carter, B, Marom E, Detterbeck F., Approaching the Patient with an Anterior Mediastinal Mass:A Guide for Clinicians; J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9: S102–S109

[6]. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood 2016; 127:2375.

[7]. Harris NL, Bhan AK. B-cell neoplasms of the lymphocytic, lymphoplasmacytoid, and plasma cell types: immunohistologic analysis and clinical correlation. Hum Pathol 1985; 16:829.

[8]. Molina T, Lin P, Swerdlow S, Cook J. Marginal Zone Lymphomas With Plasmacytic Differentiation and Related Disorders. Am J Clin Pathol 2011;136:211-22