Primary bone lymphoma (PBL) is a peculiar extranodal presentation of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) defined as a lymphoma confined to bones being usually radiologically evident.1,2 The presence of regional lymph node involvement does not exclude a diagnosis of PBL.3,4 PBL is an extremely rare entity accounting for less than 1% of NHL, around 5% of all primary extranodal NHL and 3%-7% of all malignant bone tumours.4,5 Median age at diagnosis ranges between 45 and 60 years old with a slight preponderance in male,5 and the morbidity rate of males is slightly higher than females.2 No racial or geographic predominance has been demonstrated.4,6 The underlying causes of PLB are still largely unknown,2,7 however, viral infection, immunodeficiency, organ transplantation, Paget disease of bone and inherited factors have been identified as possible causes.8 However, none of these putative associations are consistent enough to suggest a true relationship or predisposition towards the development of PBL.4

We report a case of a 62-year-old Caucasian male, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0, without any notable medical or family history, referred to the Internal Medicine consultation for a severe low back pain at least for four months. The pain was bilateral and radiated to both legs. Despite the characteristics of mechanical low back pain, it was not relieved by rest and with ibuprofen 600mg twice a day and tramadol 100mg three times a day. He also referred intense fatigue, anorexia, unintentional weight loss of about seven kilograms in three months (11% of body weight), night sweats and intermittent fever. Upon examination, patient looked older than actual age, skinny (height, 172cm; weight, 50.5kg; body mass index 17.1Kg/m2) and pale, without palpable lymph nodes, hepatosplenomegaly or neurological signs. He was admitted to the Internal Medicine ward for further investigation.

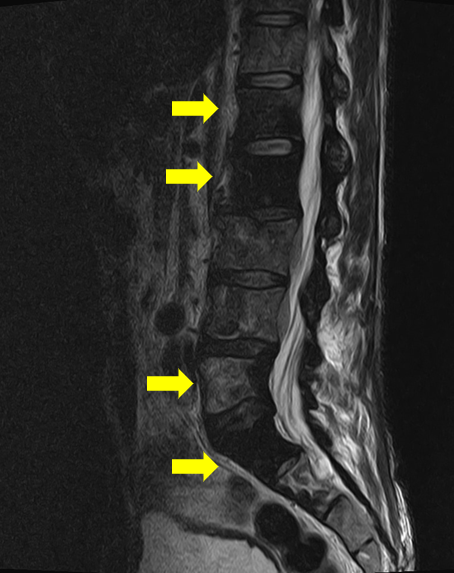

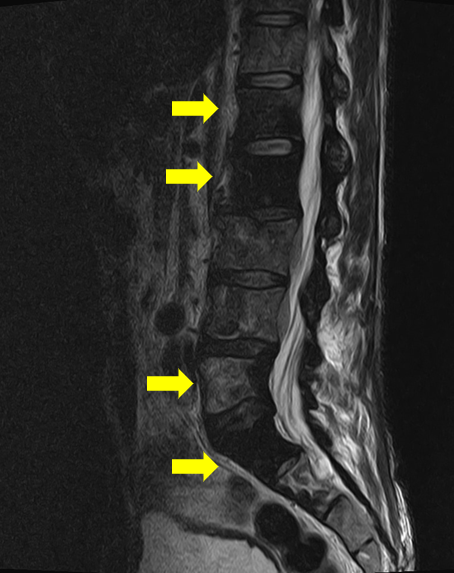

Laboratory analysis showed normocytic/normochromic anaemia (haemoglobin 8.5g/dL [11.5-16.5]) and elevation of erythrocyte sedimentation rate (105mm [<20]), alkaline phosphatase (130 U/L [46-116]), lactate dehydrogenase (1181 U/L [120-246]) and beta-2 microglobulin (3260 ng/mL [1090-2530]). Furthermore, uric acid, calcium, renal function, serum and urinary protein electrophoresis were normal. Virologic serologies and immunologic investigation were negative. The thoraco-abdominal-pelvis computed tomography (CT) revealed some mesenteric lymphadenopathy and osteosclerotic changes on L1, L2 and L5 vertebrae, without hepatosplenomegaly (Figure 1). The magnetic resonance image (MRI) showed hypointensity on both T1 and T2 images in the spine (L1, L2, L5 and S1 vertebrae), without soft tissue involvement (Figure 2). The bone scintigraphy revealed heterogenous uptake on dorsolumbar spine suggesting inflammatory disease. A CT-guided bone biopsy of the L5 vertebrae revealed a diffuse infiltration of large-sized lymphoid cells. The immunohistochemical investigation showed the following tumor-cell immunophenotype: CD20+, CD10+, CD3-, CD5-, Cyclin D1-, kappa-, Lambda- and cytokeratin MNF116-, Ki67: 61% to 70%. A Diffuse Large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) diagnosis was made. Bone marrow biopsy showed no evidence of lymphoma involvement. The patient was referred to the Haematology department.

According to the clinical and imaging examination the patient was classified as stage IVE (International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group), IV (Ann Arbor staging classification), risk group 4 (International prognostic index) [Age 62, Serum LDH 1181, Stage III–IV, Extranodal sites >1]. He was treated with 4 cycles of combined chemotherapy of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone combined with rituximab (R-CHOP) given every 21 days, together with radiotherapy (36 Gy) of lumbar spine. He achieved complete response without relapse after 2 years of follow-up.

PBL may present as a single bone lesion with or without an associated soft tissue mass arising from local extension and with or without regional lymphadenopathy or as a multifocal polyostotic disease exclusively involving the skeleton.1 Although other subtypes may also rarely occur, the DLBCL accounts for the majority of cases (70%-80% of all PBL).5 Tumor cells are generally immunoreactive for the B-cell markers CD20, CD21, CD45, and CD79a.2 Every bone is a potential site for lymphoma development, but long bones and flat bones are the most commonly affected.3,6 Femur (accounting for 29% of all cases), pelvic bones and spine are the most common sites of involvement.1,2 Primary vertebral lesion accounts only for 1.7% of all PBL, usually at the thoracic or lumbar levels 6,9 as in the case described.

The diagnosis of PBL is often complex because the clinical manifestations and imaging findings are variable and nonspecific,8 being hard to distinguish PBL from other primary bone tumours such as sarcoma or chondrosarcoma. Although the clinical presentation depends on the location of the lesion, bone pain is the most frequent presenting symptom (80%-95%).1,6 When vertebra are involved, back pain is the most common symptom,6 as in the patient described. The patients also present with a tumour mass in 30%-40% of the cases and with a pathological fracture, most frequently of the humerus, in 10%-15% of patients.1 Spinal cord compression is the first complication in 16% of cases.4

Plain radiographs of PBL usually presents as lytic or osteoblastic lesions, but MRI is a particularly useful imaging technique due to its noninvasive nature and greater anatomic detail, defining the local extent of the disease and cortical changes.4,6 The positron emission tomography CT scan (PET-CT) has increased detection of asymptomatic bone lesions as part of the initial presentation of disseminated DLBCL and can determine the extent and activity of the lesions.1,10 Indeed, the proportion of patients diagnosed with systemic disease has been more frequently recognised as better images techniques are being employed.3,10 A clinic-radiological suspicion of bone lymphoma must be confirmed by histopathological examination (morphological exam, immunohistochemistry and molecular analyses) of a diagnostic sample obtained by surgical procedure.4

R-CHOP regimens followed, if indicated, by involved-field radiotherapy remains the standard approach at any stage of DLBCL with bone involvement.1,7 There are still some issues about the therapeutic approach, such as the sequence of treatment, the choice of radiation volume and the role of surgery for fixation of pathological fractures.5 Assessment of treatment response in patients with PBL is very difficult, because the radiographic abnormalities usually persist, even after successful treatment.10 Central nervous system dissemination is an early and fatal event reported in about 5% of DLBCL.4 Thus, an accurate assessment and CNS prophylaxis may be recommended in patients with involvement of anatomic areas in close apposition to the CNS (skull and/or spine).1 Furthermore, long-term bone health preventive measures should also be taken into account in patients with PBL, including evaluation and treatment of any underlying osteoporosis and/or vitamin D deficiency.1

Overall the prognosis of PBL is good.3 The survival of patients with DLBCL is significantly related to disease stage, while it is independently associated with age, performance status and serum LDH levels.1,5 Relapses are signs of poor prognosis and pathological fracture at presentation is associated with worst outcome.5 In early-stage disease, relapses occur equally within and outside the primary sites of disease, with local and systemic relapse rates being 10% and 17%, respectively.2 Factors predicting a favourable outcome include younger age, local disease, low IPI score, chemotherapy combined with RT and good response to initial treatment.10 Chronic pain, limb dysfunction and late pathological fracture are the most common iatrogenic sequelae in patients with bone lymphoma.4

Low back pain is very frequent in clinical practice (about 26,4% in Portuguese population).11 However, the presence of constitutional symptoms and low back pain not relieved with analgesia should prompt further investigation. An early and accurate diagnosis with staging by histological and imaging techniques are crucial,7 but diagnostic procedures should not be delayed as CNS involvement may occur. PLB at early stages is relatively curable by multimodal treatment using chemo and radiotherapy.

Figura I

Lumbar spine computed tomography (longitudinal image) revealed osteosclerotic changes on L5 vertebrae (yellow arrow).

Figura II

Magnetic resonance image (longitudinal image) showed hypointensity on T2 images in the spine (yellow arrow on L1, L2, L5 and S1 vertebrae).

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Vitolo U, Seymour JF, Martelli M, Illerhaus G, Illidge T, Zucca E, et al. Extranodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(suppl 5):v91-v102.

2. Wang J, Fan S, Liu J, Song B. A rare case report of primary bone lymphoma and a brief review of the literature. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:4923-8.

3. Mikhaeel NG. Primary bone lymphoma. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2012;24(5):366-70.

4. Messina C, Christie D, Zucca E, Gospodarowicz M, Ferreri AJ. Primary and secondary bone lymphomas. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41(3):235-46.

5. Kaiafa G, Didangelos T, Bobos M, Karlafti E, Ztriva E, Kanellos I, et al. Primary Bone Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma with Multifocal Osteolytic Lesions: A Rare Entity. General Medicine: Open Access. 2018;6(1).

6. Jia P, Li J, Chen H, Bao L, Feng F, Tang H. Percutaneous Vertebroplasty for Primary Non-Hodgkin´s Lymphoma of the Thoracic Spine: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Pain Physician. 2017;20(5):E727-E35.

7. Mudawi D, Kohla S, Ibrahim F, Elsabah H, Abdelrazek M, Szabados L, et al. Primary lymphoma of bone, myeloma mimicker: a case report and review of literature. International Journal of Case Reports. 2018;3(55).

8. Zhou HY, Gao F, Bu B, Fu Z, Sun XJ, Huang CS, et al. Primary bone lymphoma: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(4):1551-6.

9. Undabeitia J, Noboa R, Boix M, Garcia T, Panades MJ, Nogues P. Primary bone non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the cervical spine: case report and review. Turk Neurosurg. 2014;24(3):438-42.

10. Hayase E, Kurosawa M, Suzuki H, Kasahara K, Yamakawa T, Yonezumi M, et al. Primary Bone Lymphoma: A Clinical Analysis of 17 Patients in a Single Institution. Acta Haematol. 2015;134(2):80-5.

11. Gouveia N, Rodrigues A, Eusebio M, Ramiro S, Machado P, Canhao H, et al. Prevalence and social burden of active chronic low back pain in the adult Portuguese population: results from a national survey. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36(2):183-97