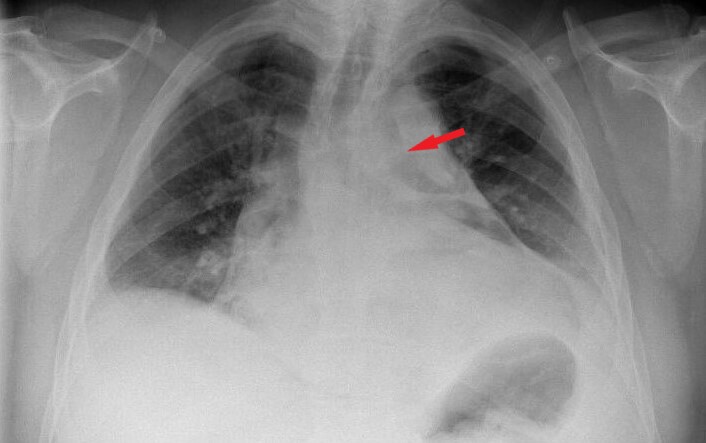

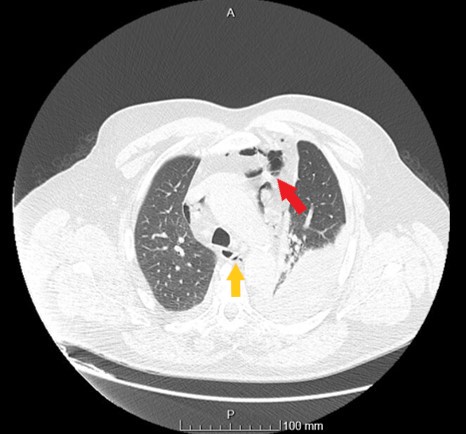

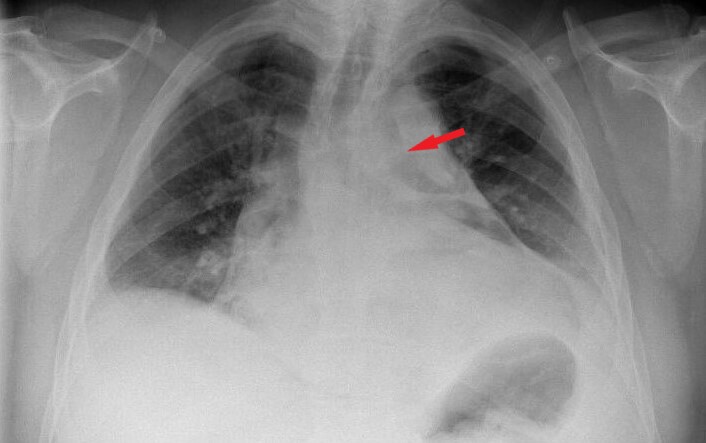

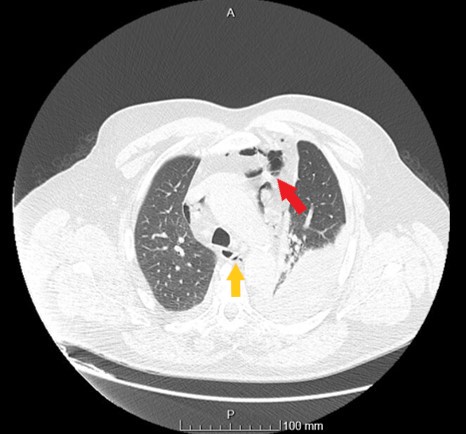

A 67-year-old man, recently medicated with an opioid for mechanical back pain, presented to the Emergency Room (ER) complaining of anterior chest pain, irradiating to the back, that appeared after an episode of vomiting. On admission he was febrile, tachycardic and had diminished respiratory sounds on the inferior left pulmonary region, with a pulse oximetry of 90%. Blood gas analyses showed hypoxemic respiratory failure and a lactate level of 3.24 mmol/L. ECG was normal, except for sinus tachycardia. Laboratory investigations revealed normal levels of C-reactive protein, troponin and d-dimer, but chest x-ray (posteroanterior view) showed a tubular artery sign (Fig. 1), compatible with a pneumomediastinum, later confirmed on CT: large anterior pneumomediastinum, also present next to the posterior section of distal esophagus (Fig. 2), with no evidence of tracheal perforation, suggestive of an esophageal rupture. The case was discussed with General Surgery and the patient was submitted to a near total esophagectomy and then admitted to the Intensive Care Unit for recovery.

Chest pain is responsible for approximately 7.6 million visits to the ER each year.1 It represents a challenging diagnosis, since it may have many possible causes.1,2 Chest pain related to esophageal disorders may be particularly difficult to diagnose and to distinguish from a cardiac origin pain.1,2 Pneumomediastinum, when present, may alert to this possibility, particularly when a patient presents with a history of prior vomiting that can suggest an esophageal rupture.3,4 Although unusual, pneumomediastinum may be an emergent cause of chest pain, so clinicians should always be aware of its possibility, especially since its diagnosis may be suspected after careful examination of a chest x-ray.4-6 This case is an example of that: given the clinical picture, the hypothesis of acute coronary syndrome, pneumonia with pleural effusion or pulmonary embolism were primarily considered, but x-ray findings pointed to the hypothesis of pneumomediastinum, that was later confirmed with CT and attributed to an esophageal rupture.

Figura I

Figure 1. Tubular artery sign (air in the mediastinum outlining major aortic branches) on chest x-ray (posteroanterior view) (red arrow).

Figura II

Figure 2. Pneumomediastinum on chest CT (transversal view): anterior (red arrow) and next to the posterior section of distal esophagus (yellow arrow).

BIBLIOGRAFIA

. Hollander JE, Chase M. Evaluation of the adult with chest pain in the emergency department. UpToDate 2019. (accessed October 2019). Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-the-adult-with-chest-pain-in-the-emergency-department

2. Erhardt L, Herlitz J, Bossaert L, Halinen M, Keltai M, Koster R et al. Task force on the management of chest pain. European Heart Journal. 2002. 23, 1153–1176

3. Banki F, Estrera AL, Harrison RG, Miller CC, Leake SS, Mitchell KG et al. Pneumomediastinum: etiology and a guide to diagnosis and treatment. The American Journal of Surgery. 2013; 206, 1001-1006

4. Caceres M, Ali SZ, Braud R, Weiman D, Garrett HE. Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum: A Comparative Study and Review of the Literature. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008; 86:962–6

5. Ferreira LA, Barros M, Costa JF, Alves FC. Radiologic features of pneumomediastinum: from classic signs to clinical management. European Society of Radiology. 2015; C-2405; doi: 10.1594/ecr2015/C-2405

6. Dixit R, George J. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum with a classical radiological sign. Lung India. 2012; 29(3): 295–296