INTRODUCTION

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is an acute or subacute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy with an annual incidence between 0.6 and 4 per 100 000 people. It’s 1.5-2 times more frequent in males than females.1

The symptoms are, usually, preceded by a flu-like event or gastroenteritis in about two thirds of cases. Its physiopathology remains unknown but has been proposed that the infection creates an immune response which cross-reacts with Schwann cell antigens, leading to peripheral nerve damage.2

Diagnostic criteria include areflexia with progressive bilateral weakness in the arms and legs and this can be complicated by hypoventilation due to respiratory muscle and diaphragm weakness, retained secretions due to loss of cough reflex, loss of airway protective mechanisms and autonomic dysfunction (tachycardia/bradycardia, other arrhythmias, hyper/hypotension). The fatality rate is 5% but up to 20% of the patients develop long term neurological sequelae.3

Since 1985, several cases of GBS among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected individuals have been reported, including as first HIV manifestation.4

CASE REPORT

A 41-year-old male was admitted with an acute weakness of the lower limbs and inability to walk for about 24 hours. He referred that, two weeks prior to admission, he had had 4 to 5 evacuations/day of watery stools that resolved in 3 days, without any medication. He denied other symptoms.

He had a history of arterial hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia and psoriatic arthritis. He was medicated with olmesartan/ hydrochlorothiazide 20/12.5mg id; metformin 1000mg id; rosuvastatin 10mg id; methotrexate 10mg/week; omeprazol 20mg id.

Heterosexual intercourses with risk for HIV transmission were reported and he had been tested HIV-negative about six-months before.

On physical examination, he had symmetrical weakness of both proximal and distal muscles of the lower limbs (grade 3/5) and normal strength in the upper limbs. Cranial nerves were normal. There was hypotonia and absent reflexes in lower limbs with bilateral absent plantar reflex. There wasn’t any sensory deficit. Bladder and bowel functions were intact. He hadn’t respiratory insufficiency. Examination of other systems was irrelevant.

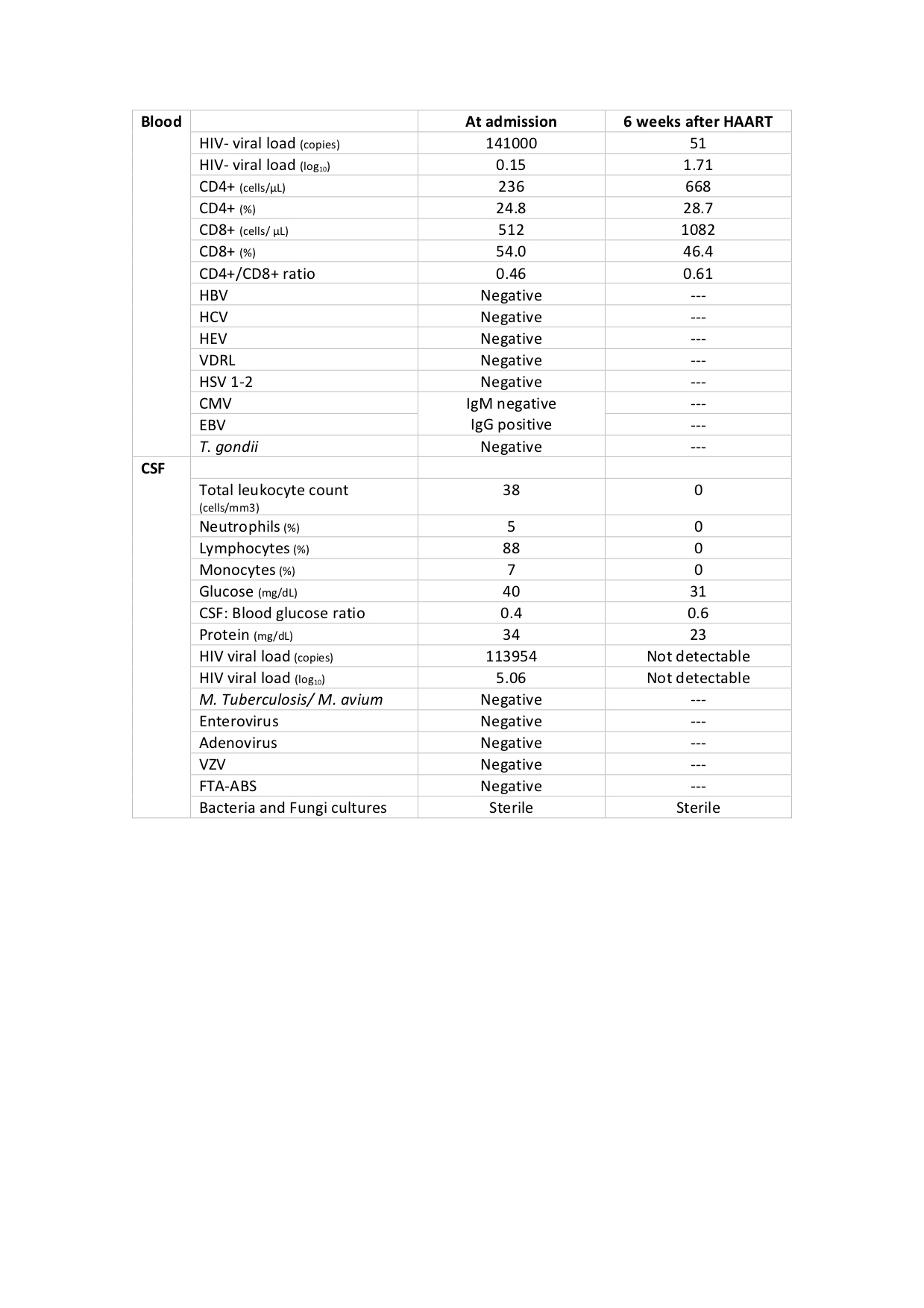

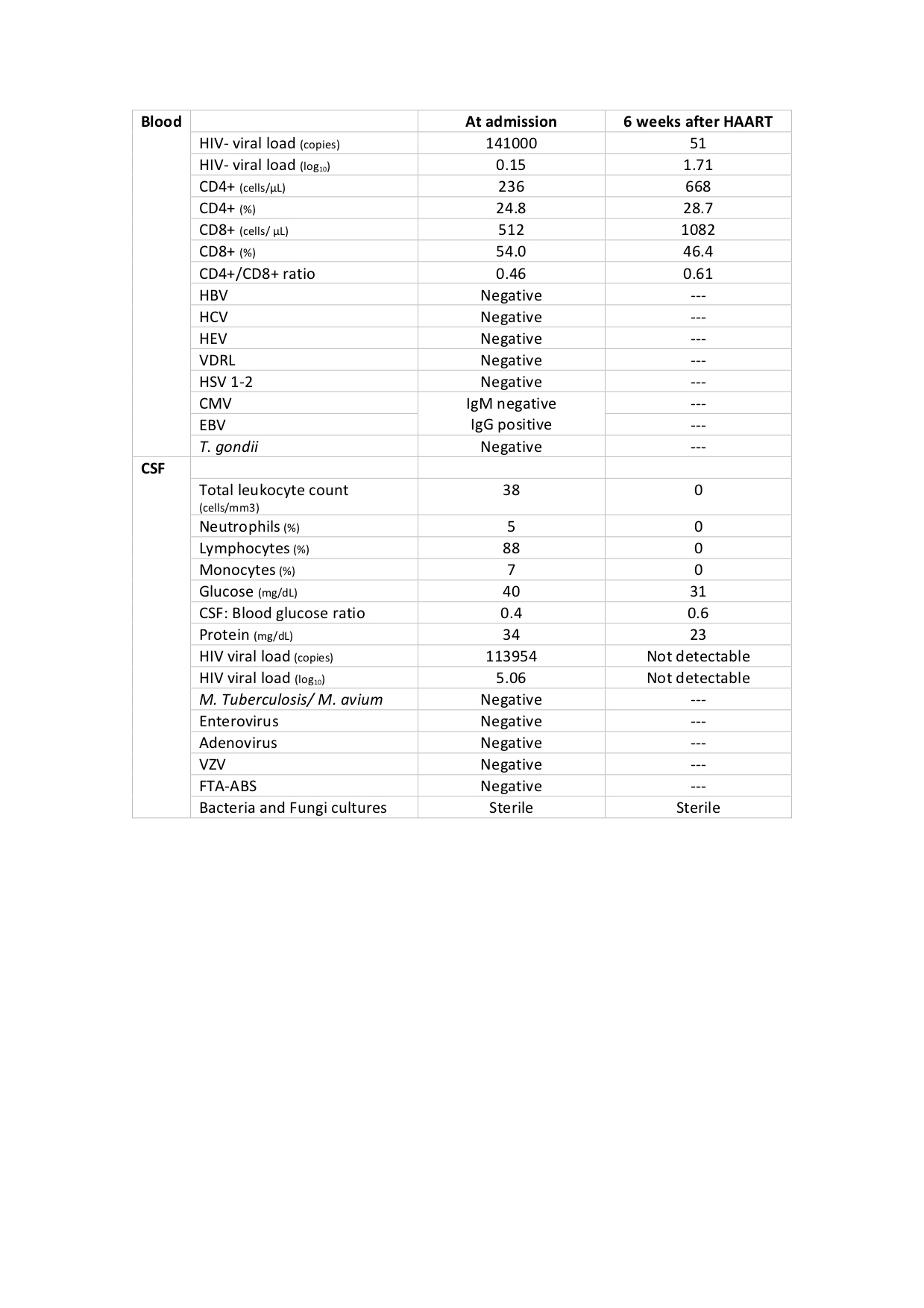

Blood tests showed a normal white blood cell count (WBC) and negative C-reactive protein. Cerebral and spinal computed tomography scans were unremarkable. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed albuminocytological dissociation, proteins of 34mg/dL with pleocytosis and low glucose (Table 1). Electromyography showed severe axonal polyneuropathy. A presumptive diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome was made and the patient started on intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) at 400mg/kg/day for 5 days.

The aetiology investigation showed positive HIV-1 antibodies by ELISA test, later confirmed by Western blot.Plasma HIV-viral load was 141000 copies/mL (6.15log), CD4+T-cell count was 236 cells/mm3(24.8%), whereas CD8+T-cell count was 512 cells/mm3(54.0%), with CD4+/CD8+ratio of 0.46.Further blood analysis showed negativity for hepatitis B, C, E, syphilis,Cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barrvirus,Herpes simplex1- 2 virus andToxoplasma gondii(Table 1).

CSF analysis revealed a HIV viral load of 113954 copies/mL.It was negative, by Polymerase Chain Reaction essay, for varicella zoster virus, enterovirus, adenovirus (Table 1).

There was no evidence ofSalmonellaspecies,Shigella,E.coliO157,CampylobacterorCryptosporidiumoocysts in faecal samples.

The patient started a fixed dose combination therapy with ABC/3TC/DTG and was discharged 23 days after admission with improved mobility but still requiring walking aids.

Six weeks after initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), he was re-evaluated in an outpatient setting. He was walking with a cane and was otherwise asymptomatic.CD4+T-cell count was 668 cells/mm3(28.7%) while plasma HIV-viral load had decreased drastically (Table 1).The patient maintains antiretroviral compliance, regular physiotherapy and outpatient clinical follow-up.

DISCUSSION

The association between GBS and HIV infection has been reported frequently over the last 25 years, mainly in the form of case reports and series5. Possible mechanisms include direct HIV neurotoxicity or autoimmunity. Typical neural histology supports an antibody-mediated process and high titters of autoantibodies to myelin sheath glycosphingolipids are found in the serum of affected patients. The presence of these anti-ganglioside antibodies at low CD4 counts suggests that abnormal immunoregulation in HIV may precipitate a paradoxical rise in autoantibodies, resulting in GBS.6

The relation between GBS and the stage of HIV infection is unclear. Although most authors describe GBS as a manifestation of early HIV infection or even seroconversion, numerous cases of GBS in advanced immunosuppression have been reported, with CD4 counts as low as 4 cells/mm3.7The onset of GBS, in this case, coincided with the acute retroviral syndrome of HIV, during the phase of initial immune reconstitution following serologic conversion.

Another consideration, in this report, was the use of methotrexate to treat psoriatic arthritis. This drug has been associated to myelitis and GBS due to its potential neurotoxicity7. But, it usually presents with other signs such as encephalopathy and seizures6, so a possible causality between methotrexate and GBS was dismissed.

The history, examination and clinical disease course of HIV-GBS resembles non-HIV cases. Nerve conduction studies also reveal similar patterns. Elevated CSF protein is found in GBS of any aetiology, but WBC pleocytosis is seen more frequently in HIV-positive patients.6

HIV is a neurotropic virus so central nervous system inflammation and detection of HIV-RNA in the CSF can occur in the early stages of acute infection. Even after HAART, HIV can still be detected. Therefore, the choice of HAART regimen must incorporate drugs which effectively cross the blood-brain barrier. The nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors zidovudine, lamivudine and abacavir, and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors efavirenz and nevirapine have a good penetration in the central nervous system but protease inhibitors are less reliable.8

Plasmapheresis and IVIG are also used to treat GBS in HIV-infected individuals with results that range from ineffective to total response. Due to its greater convenience with overall comparable cost and equal efficacy, IVIG remains the preferred choice. Although less common, prednisone 1 mg/kg/day can be used.7

There is no sufficient evidence on long-term outcomes in HIV-positive patients, however, it has been suggested that, when compared with HIV-negative cases, recurrent GBS is more frequent especially during seroconversion and immune reconstitution following HAART therapy.9

In conclusion, it is important to consider HIV testing in high-risk individuals with newly found neurological deficits as GBS may be its first manifestation. Further research is needed to evaluate the immunologic effect on HIV-1 infection, to clarify the detailed mechanisms of immunomodulation and to determine the best therapeutic approach to these patients.

Figura I

Table 1. Blood and cerebrospinal fluid analysis at admission and 6 weeks after initiating HAART. CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid; HAART: highly active antiretroviral therapy; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HEV: hepatitis E virus; VDRL: venereal disease research laboratory; HSV 1-2: Herpes simplex virus 1 and 2; CMV: cytomegalovirus; EBV: Epstein-Barr virus; T. gondii: Toxoplasma gondii; M.tuberculosis/ M. avium: Mycobacterium tuberculosis/ Mycobacterium avium; VZV: varicella zoster virus: FTA-ABS: fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1.Hughes RA, Cornblath DR. Guillain-Barré syndrome.The Lancet2005; 366: 1653-66

2.Seneviratne U. Guillain-Barré syndrome.PostgraduateMedical Journal, vol. 76, no. 902, pp. 774–782, 2000

3.Yuki N, Hartung HP. Guillain–Barré syndrome.N Engl J Med2012; 366:2294–2304

4.Castro G, Bastos PG, Martinez R, Castro Figueiredo JF.Episodes of Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with the acute phase of HIV-1 infection and with recurrence of viremia.Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria, vol. 64, no. 3, pp. 606–608, 2006

5.Espinosa M, Pulido F, Rubio R, Lumbreras C,et al.Peripheral facial palsy leading to the diagnosis of acute HIV infection.HIV & AIDS Review2016; 15:88–90

6.Willison HJ, Jacobs BC, van Doom PA.Guillain-Barre syndrome.The Lancet, 2016.388(10045): p. 717–727

7.Brannagan TH, Zhou Y. HIV-associated Guillain–Barré syndrome.J Neurol Sci2003; 208:39–42

8.Ferretti F, Gisslen M, Cinque P, Price RW. Cerebrospinal fluid HIV escape from antiretroviral therapy.Curr HIV/AIDS Rep2015;12: 280–288

9.Varshney AN, Anand R, Bhattacharjee A, Prasad P,et al. HIV seroconversion manifesting as Guillian–Barré syndrome.Chin Med J2014; 127:396