Introduction

Bile duct hamartomas are a rare cause of multiple benign hepatic lesions. Also referred to as Von Meyenburg complexes (VMC), multiple bile duct hamartomas and biliary microhamartomas were first described in 1918, by the Swiss pathologist Hanns von Meyenburg.1 These lesions typically cause no symptoms or disturbances in liver function and are usually incidental findings on imaging, laparotomy or autopsy.2 Clinical relevance is attributed to the fact that they can mimic liver metastasis, abscesses and other cystic liver diseases, as well as cirrhosis. VMC consist of small (<1 cm), usually multiple and nodular cystic lesions, rising from ductal plate malformations of the smallest intrahepatic bile ducts.3 Histological findings reveal cystic dilation of the bile ducts surrounded by abundant fibrous stroma.4

The reported incidence of biliary hamartomas ranges from 0.5% to 5.6% in autopsy studies.5

The authors present a case of intrahepatic bile duct malformation to stress the importance of differential diagnosis.

Case Report

A 57 year-old woman was referred to internal medicine outpatient clinic for progressively worsening pain and swelling of her hands, knees and ankles over the last 4 to 5 months. She denied fever, chills, night sweats, nausea or vomiting, weight loss, rash, cough, gastrointestinal dysfunction, jaundice, hematemesis or bloody stools. Past medical history was relevant for hypertension treated with irbesartan (150mg/d) and smoking (75 pack- years). Clinical examination was unremarkable.

Her workup prior to presentation to our hospital included an abdominal ultrasound, showing multiple tiny hyperechoic nodules over both lobes of the liver, and an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan, which revealed multiple small low-density lesions over both lobes, described as cirrhosis. The intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts were not dilated.

Based on these clinical findings, a presumptive diagnosis of cirrhosis with unknown etiology was made and a further workup was performed. Laboratory studies were unremarkable such as alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, albumin, bilirubin level, alkaline phosphatase, urea, creatinine, electrolytes, international normalized ratio, prothrombin time and alpha-fetoprotein. Moreover, rheumatoid factor, serum angiotensin converting enzyme, serum protein electrophoresis and complement factors C3 and C4 were within the normal range. Serologies for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis A, B and C, Epstein–Barr, Herpes simplex, and Cytomegalovirus were negative. Additional laboratory studies revealed a complete blood count and C-reactive protein (2.18 mg/dl [normal <5mg/dl]) within normal limits, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (45mm/h) showed slight elevation. Autoimmune workup for liver disease, including anti-nuclear antibodies, smooth muscle antibodies, anti-mitochondrial antibodies, liver kidney microsomal antibodies and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative. Metabolic profiles including iron studies, alpha-1-antitrypsin and ceruloplasmin were normal.

Abdominal ultrasonography (Fig. 1) was repeated, revealing multiple small hyperechoic nodules, distributed uniformly throughout the liver. Endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract and colonoscopy were also performed and revealed normal results. Furthermore, transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal cardiac ejection fraction and fibroscan-elastography of the liver revealed mild fibrosis.

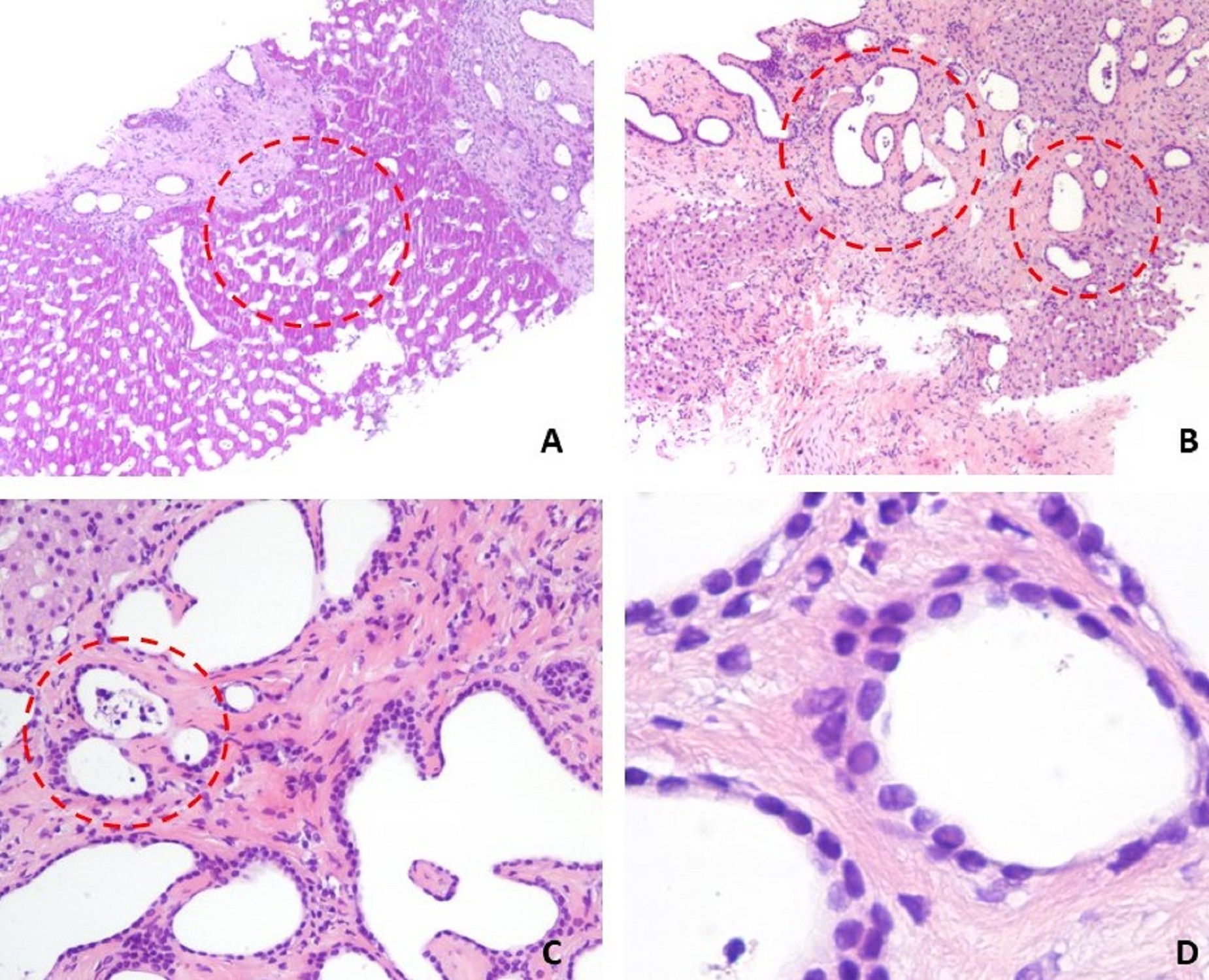

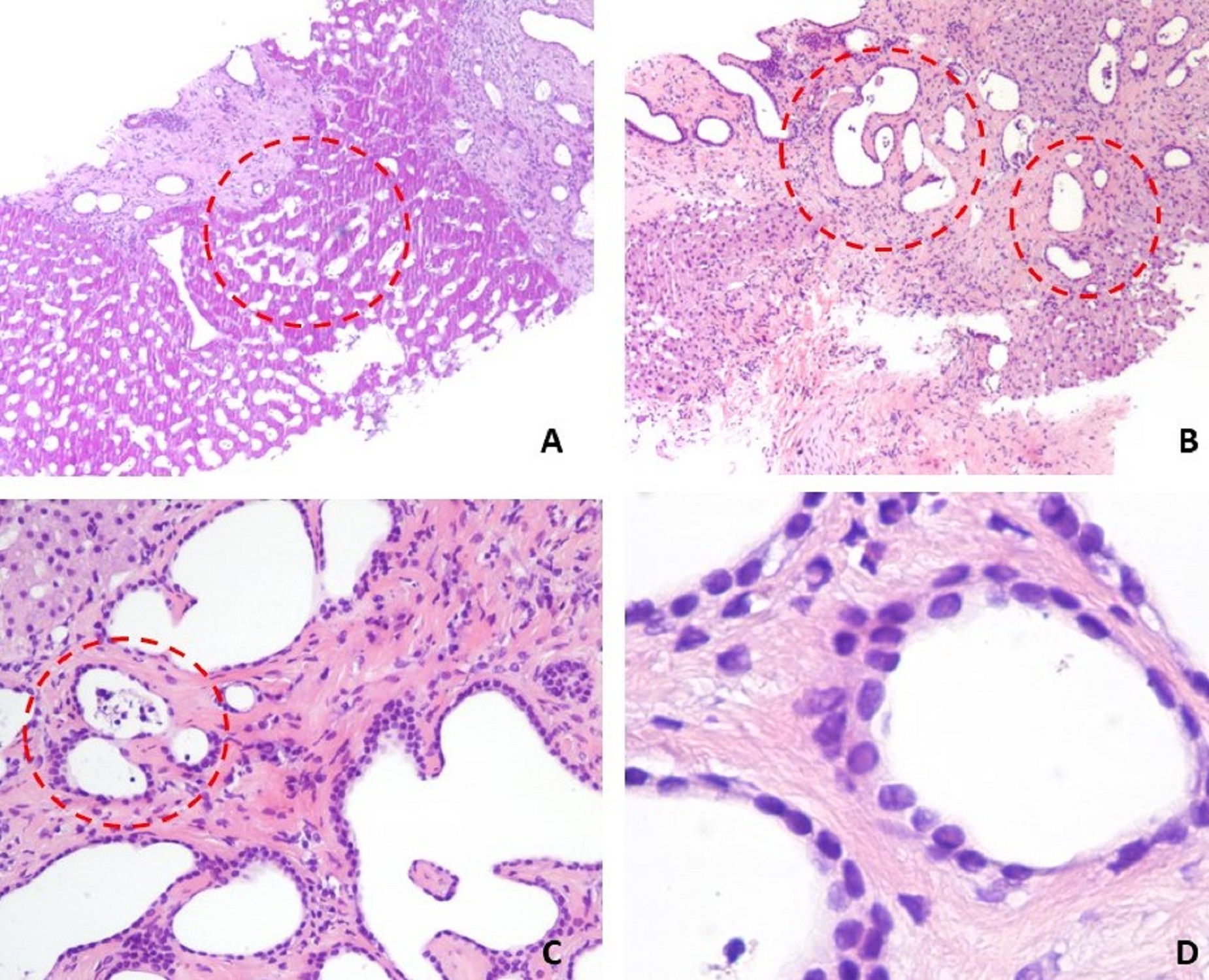

Due to inconclusive diagnosis by imaging studies, an ultrasound-guided core liver biopsy was performed and histopathology examination (Fig. 2) revealed diffuse bile duct hamartomas, arising from the portal region. Hematoxylin-eosin staining showed bile duct microhamartomas, consisting of circumscribed fibrous areas containing many irregularly dilated bile duct structures and only a few narrowed vessels in the portal region, without histologic evidence of advanced fibrosis.

Discussion

Bile duct hamartomas, also known as VMC, were first described in the early 20th century, as a congenital cystic lesion.1 VMCs are benign hepatic malformations, composed of small dilated cystic bile ducts, lined by fibrous stroma.4 These lesions typically cause no symptoms or disturbances in liver function and thus, in most instances, VMC are diagnosed incidentally, on the basis of their unique radiologic appearance.2,6

However, to date, there are multiple case reports on the different clinical manifestations of VMCs, including non-specific abdominal pain, progressive abdominal distension, obstructive jaundice, portal hypertension, infectious complications and malignant transformation to cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma.7,8

The exact pathogenesis of VMC remains unclear and it is usually considered as an interruption of the remodeling of ductal plates during the late phases of embryologic development of the intrahepatic bile ducts.2 Ductal plates malformation is involved in the genesis of not only biliary hamartomas but also congenital hepatic fibrosis, liver cysts in autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease, polycystic liver disease and Caroli’s disease. Thus, biliary hamartomas are known to be associated with these disorders.9

The most important differential diagnosis of bile duct hamartomas are liver metastases, which would interfere with different treatment strategies, especially when the patient has a history of malignancy.10 Other similar diseases include primary hepatocellular carcinoma, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and circumscribed inhomogeneous fatty liver, simple hepatic cyst, small liver abscess and lymphoma.11

Macroscopically, VMC usually appear as multiple, greyish-white nodules scattered throughout both liver lobes, predominantly in the subcapsular and periportal areas, sizing between 1 and 15 mm. Most of them are smaller than 5 mm but some may reach up to 3 cm.12 Microscopically, VMC appear as small cystic dilated bile ducts, lined by a single layer of cuboidal epithelium cells. Their shape is round or irregular. They are embedded in abundant fibrous stroma and may contain bile-stained granular materials. VMC do not communicate with the biliary tree, which maintains its normal structure.13

On ultrasonography, liver parenchymal echotexture often appears heterogeneous and coarse and VMC show up as multiple micro-nodules, either hypo- or hyperechoic.12 They often appear as target lesions, with central hyper-echogenicity, due to cholesterol crystals precipitating out of solution within the dilated bile ducts.12 On CT scans, VMC appear irregular, with low attenuation areas that normally do not enhance with contrast. To date, magnetic resonance imaging is considered the best imaging tool to assess VMC.14

Liver biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosing and distinguishing VMCs from other hepatic lesions, with key histologic features, including cystic bile duction dilation within a dense fibrous stroma.14Indeed, liver biopsy is obligatory in case of suspicion of a neoplastic process as VMC can be easily confused with metastatic disease of the liver on imaging. Bile duct hamartomas can also be differentiated from Caroli’s disease by their lack of communication with the biliary tree.9

These complexes do not require treatment, but long-term follow-up is indicated due to the possible malignant potential of this condition.15

In the present case, VMC were diagnosed incidentally, considering the absence of a relation with the patient´s clinical condition. The patient is currently asymptomatic and is undergoing ambulatory follow-up, without evidence of malignant transformation.

In conclusion, VMC are an overall rare finding, usually causing no symptoms or liver function test abnormalities; imaging manifestations of VCM are known to be various and therefore confusing, with biopsy remaining the standard for definitive diagnosis. In our case, the presence of hepatic nodules observed at ultrasonography and the inconclusive diagnostic workup led to a liver biopsy, reaching definitive diagnosis of VMC.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Maria Fernanda Silva e Cunha (Department of Pathology, Centro Hospitalar de Leiria), for the assiduous availability.

Figura I

Figure 1. Liver ultrasonography demonstrating the presence of hyperechoic liver lesions (white arrows).

Figura II

Figure 2. Histopathology findings of liver biopsy showed (hematoxylin-eosin stain): (A) preserved hepatic tissue with irregular and dilated biliary ducts (dashed red line circle); (B) multiple dilated and disorganized bile ducts embedded in fibrous stroma (dashed red line circle); (C) bile-like materials observed inside the dilated bile ducts (dashed red line circle) and (D) the epithelial cells of the duct are single layered, cuboidal.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. H vM. Über die Zyztenleber. Beitr Pathol Anatom 1918; 64: 47-532.

2. Salo J, Bru C, Vilella A, et al. Bile-duct hamarto¬mas presenting as multiple focal lesions on hepatic ultrasonography. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992; 87: 221-3.

3. Redston MS, Wanless IR. The hepatic von Meyenburg complex: prevalence and association with hepatic and renal cysts among 2843 autopsies. Mod Pathol. 1996; 9: 233-7.

4. Desmet VJ. Congenital diseases of intrahepatic bile ducts: variation on the theme “ductal plate malformation”. Hepatology 1992; 16: 1069–083.

5. Cook JR, Pfeifer JD and Dehner LP. Mesenchymal hamartoma of the liver in the adult: association with distinct clinical features and histological changes. Hum Pathol 2002; 33: 893–8.

6. Vitule LF, Simionato FM, Melo ML, Yoshitake R. Von Meyenburg complex: case report and literature review. Radiol Bras. 2010;43:408–10.

7. Sinakos E, Papalavrentios L, Chourmouzi D, et al. The clinical presentation of Von Meyenburg complexes. Hippokratia. 2011;15:170–3.

8. Silveira I, Mota F, Ferreira JP, Dias R, Leuschner P. Complexo de Von Meyenburg ou Metástases Hepáticas? Caso Clínico e Revisão da Literatura. Acta Med Port 2014 Mar-Apr;27(2):271-3.

9. Zheng RQ, Zhang B, Kudo M, Onda H, Inoue T. Imaging findings of biliary hamartomas. World J Gastroenterol 2005;13: 6354–9.

10. Mimatsu K, Oida T, Kawasaki A, Aramaki O, Kuboi Y, Katsura Y and Amano S. Preoperatively undetected solitary bile duct hamartoma (von Meyenburg complex) associated with esophageal carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol 2008; 13: 365-8.

11. Nagano Y, Matsuo K, Gorai K, Sugimori K, Kunisaki C, Ike H, et al. Bile duct hamartomas (von Meyenburg complexes) mimicking liver metastases from bile duct cancer: MRC findings. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:1321–3.

12. Lung PF, Jaffer OS, Akbar N, Sidhu PS, Ryan SM. Appearances of Von Meyenburg complex on cross sectional imaging. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2013;3:22.

13. Semelka RC, Hussain SM, Marcos HB, Woosley JT. Biliary hamar-tomas: solitary and multiple lesions shown on current MRtechniques including gadolinium enhancement. J Magn ResonImaging 1999;10:196-201.

14. Salles VJ, Marotta A, Netto JM, et al. Bile duct hamartomas—the von Meyenburg complex. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2007;6:108–9.

15. Parekh V, Peker D. Malignant transformation in Von-Meyenburg complexes: Histologic and immunohistochemical clues with illustrative cases. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2015; 23: 607-14.