Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia encountered in clinical practice and one of the major causes of stroke, heart failure, sudden death and cardiovascular morbidity in the world.1,2

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (WPW) is a conduction disorder of the heart characterized by an abnormal accessory pathway, in which atrial impulses are transmitted to the ventricle in addition to the normal atrioventricular conduction. In WPW, the accessory pathway enables a rapid anterograde conduction which can outpace slower atrioventricular (AV) node conduction, resulting in a relatively rapid depolarization of the ventricles. These alterations in impulse conduction cause a typical electrocardiogram (EKG) pattern: a short PR interval together with a wide QRS complex and a delta wave. Patients with WPW syndrome may commonly present palpitations, syncope and sudden death.3,4

The combination of WPW with AF constitutes a potentially fatal arrhythmia. The presence of an anterograde accessory pathway with a short refractory period allows rapid conduction of the electrical impulse to the ventricles, which results in high ventricular rate and subsequent risk of degeneration to ventricular fibrillation (VF).2,5

Case Description:

The authors present the case of a 42 year-old woman who attended the emergency department complaining of palpitations and general malaise that had begun suddenly that same day. The patient denied fever, dizziness, chest pain, shortness of breath, or altered consciousness. She also denied suffering similar episodes in the past.

The patient had a history of WPW syndrome and unspecified thyroid disease. She was on no regular medication.

In initial assessment, the was afebrile, normotensive (arterial pressure: 100/78 mmHg) but tachycardic (Heart rate: 140-300 beats per minute). She showed no signs of respiratory distress, with peripheral oxygen saturation of 96% at room air. Cardiac auscultation confirmed tachycardic and arrhythmic heart sounds but no heart murmurs. Pulmonary auscultation was symmetrical and there were no abnormal respiratory sounds. Lower limbs showed no signs of edema or diminished peripheral perfusion.

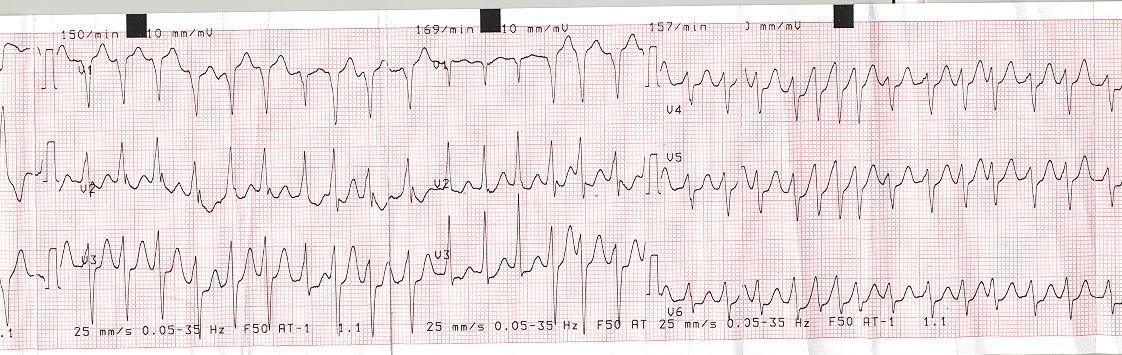

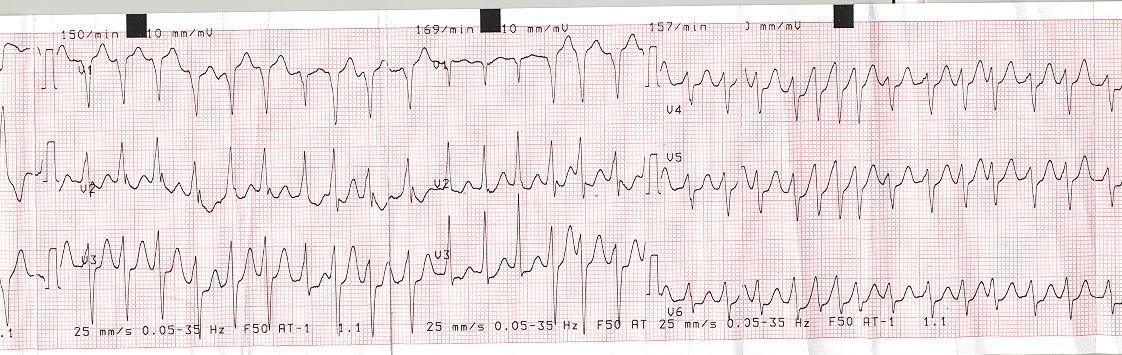

Initial EKG revealed AF with rapid ventricular rate (160 to 300 beats per minute), with alternate conduction between accessory and normal pathways (Fig. 1).

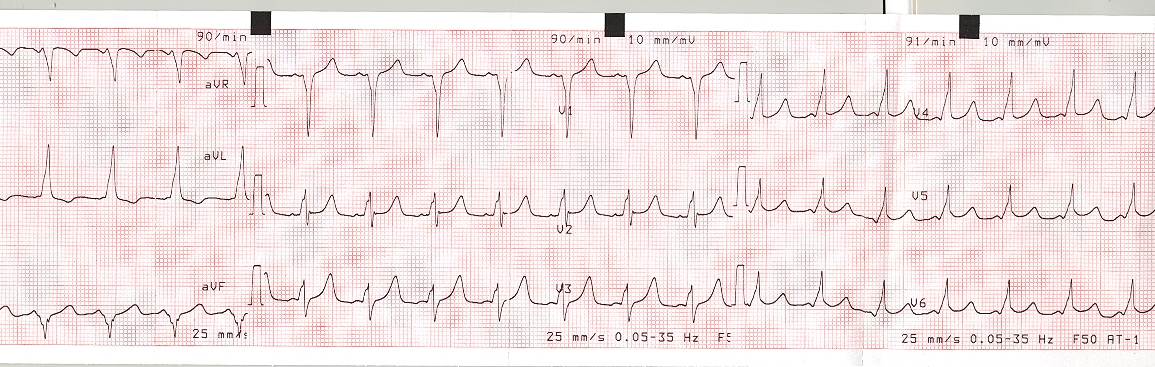

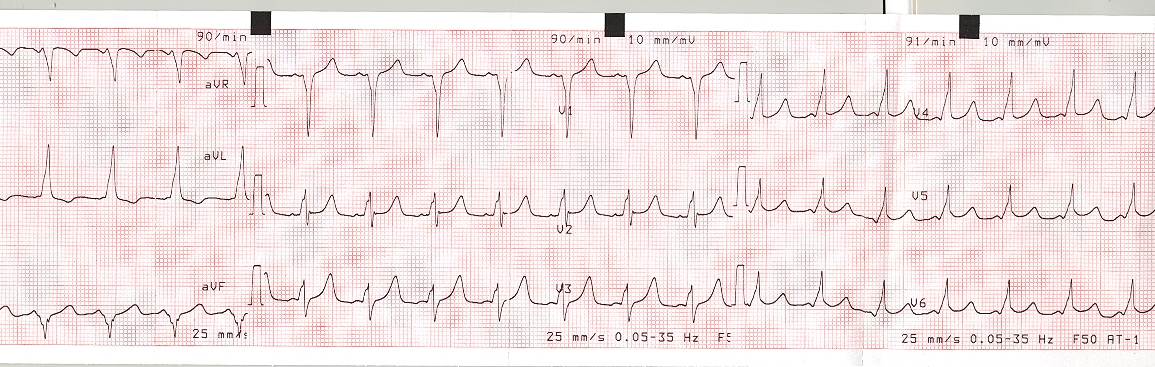

Given the high risk of degeneration to VF, it was decided to perform urgent electrical cardioversion, and a 200 J electric shock was delivered. Post-cardioversion EKG showed sinus rhythm with signs of ventricular pre-excitation (Fig. 2).

During hospitalization, a thorough study was performed, including blood tests with thyroid function that were normal.

Transthoracic cardiac ultrasound ruled out functional and morphological alterations, such as Ebstein’s anomaly.6

An electrophysiology study was also performed, which included ablation of the accessory pathway identified in the right posterior septal region.

Discussion:

The risk that patients with WPW will also develop AF is estimated at 15% and is of special concern in these patients.5 During pre-excited AF, the atria can discharge at a rate higher than 300 impulses per minute. These impulses are usually blocked by the AV node owing to decremental conduction. However, an accessory pathway makes 1:1 conduction possible, with ventricular rates reaching 300 bpm, potentially degenerating to VF.4

Therapeutic options in such situations differ from the usual treatment options of isolated AF. Immediate cardioversion is imperative, even when there are no signs of low cardiac output.5

Many of the drugs commonly used to control ventricular rate are potentially harmful in these cases. Treatment with AV nodal blockers is contraindicated as these drugs slow the impulse conduction through the atrioventricular node without prolonging the refractory period of the accessory pathway. This promotes conduction through the accessory pathway, accelerating the ventricular rate and precipitating hemodynamic collapse and VF. Accordingly, drugs such as verapamil, diltiazem, adenosine, digoxin and amiodarone can precipitate VF and should not be used. Beta blockers pose a similar potential risk, although data on the administration of these agents in situations of rapid AF in patients with WPW are scarce.5

Ibutilide or procainamide may slow the rate of conduction over the accessory pathway and decrease the ventricular rate. They may be used in hemodynamically stable patients presenting AF with conduction over an accessory pathway.1,5

Catheter ablation of the accessory pathway is recommended in symptomatic patients with pre-excited AF, especially if the accessory pathway has a short refractory period.

2 Once the accessory pathway has been eliminated, the process of selecting pharmacological therapy to manage AF is the same as for patients without pre-excitation.

5Figura I

Electrocardiogram on admission, showing atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular rate, and alternate conduction with an accessory pathway.

Figura II

Electrocardiogram after electrical cardioversion, showing sinus rhythm with signs of ventricular preexcitation.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Prystowsky E. N., et al. Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Subcommittee on Electrocardiography and Electrophysiology, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1996;93(6):1262-77

2. Kirchhof P., et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;50(5):e1-e88.

3. Marrakchi S., et al. Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome Mimics a Conduction Disease. Case Rep Med. 2014; 2014: 789537.

4. Silverman A, Taneja S, Benchetrit L, Makusha P, McNamara RL, Pine AB. Atrial Fibrillation in a Patient With an Accessory Pathway.J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2018;6:2324709618802870.

5. January C.T., et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation (2014);130(23):2071-104.

6. Etheridge S. P., et al. Life-Threatening Event Risk in Children With Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome: A Multicenter International Study. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;4(4):433-44.