INTRODUCTION

The worldwide incidence of Miller Fisher Syndrome (MFS) is approximately 1 to 2 in 1000000, usually affecting more men than women and presenting a mean age of 43.6 years at the onset of disease.1 It is thought to result from an acute autoimmune cross-reaction between peripheral nerve antigens and microbial/viral components through molecular mimicry that leads to the destruction of the myelinating components of the central and peripheral nervous system.1,2

MFS is usually associated with an infection preceding the neurological symptoms.1 Campylobacter jejuni infection is usually associated with an axonal-onset variant; and affected patients commonly experience more rapid deterioration.2

CASE REPORT

A 72-year-old man presented at the emergency room with blurred vision in the right eye, slurred speech and dysphagia for the two previous days. His medical background included a stable multiple myeloma, hypertension, type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia. He referred having taken the flu vaccine 5 months before admission and having flu symptoms for the last 2 weeks.

At the emergency room, he was vigil, had a slurred but coherent speech with dysarthria, was able to name and repeat. He presented left eyelid ptosis, no visual field loss and isochoric pupils with pupillary reflexes present. (figure 1) Left extraocular movements were reduced and the patient wasn’t capable of abducting the left eye. He presented left facial paralysis. (figure 2) No muscle strength or sensitivity loss were referred. Cerebellar tests had no changes.

Blood analyses were normal. He performed a cerebral and cervical simple and angio computed tomography revealing no parenchymal or vascular lesions, but showing multiple lytic injuries of cervical vertebrae. The patient was admitted for study.

During his hospital stay, he maintained his neurologic deficits. During the first days, he further presented limitation of the abduction of both eyes, diplopia that was corrected with monocular occlusion, severe dysphagia, distal left arm muscle strength reduction (moved against gravity but without resistance).

At this point four major diagnoses were under consideration: Ischemic stroke, oncologic progression, Central Nervous System infection and MFS. Blood analysis and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) didn’t show any alterations. We contacted Neuroradiology colleagues and the patient’s Hematologist to review MRI images and his oncology state and oncologic disease progression was excluded.

On the 5th day, the patient progressed to left eyelid ptosis, abduction limitation of both eyes, left facial paralysis, lower-right facial paralysis, dysarthria, left finger-nose test dysmetria and reduced, symmetrical, bilateral osteotendinous reflexes (bicipital, radial and aquilian).

We performed a lumbar puncture (LP) and cerebrospinal liquor was sent to cell counting, biochemistry, microbiology (bacteria, mycobacteria and viral panel) and antiganglioside GQ1b antibody investigation. LP results revealed 2 leucocytes and no albumino-cytologic dissociation.

On the same day, the patient had a pulmonary arrest needing orotracheal intubation and an Intensive Care Unit. At this moment, the patient presented complete ophthalmoplegia, left ptosis, bilateral facial paralysis, dysphagia, dysarthria, respiratory failure, reduced muscle strength in the 4 limbs and generalized areflexia. He started on intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) 30g/day (0,4g/kg) for 5 days for the presumptive diagnosis of Guillain Barré Syndrome (Miller-Fisher variant). He did an electromyography that revealed a peripheral sensorimotor polyneuropathy in the upper and lower limbs, axonal lesion in facial and trigeminal nerves and absent cubital F-wave and prolonged posterior tibial F-wave, findings consistent with Miller-Fisher Syndrome. Campylobacter was identified in the patient’s stool through polymerase chain reaction methods, although he never presented gastrointestinal symptoms.

The internment was longer than expected due to lower tract respiratory infections.

On the 10th day, the patient was extubated and needed a tracheostomy (image 3); on the 20th he initiated a multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme with physiotherapy, occupational and speech therapy and on the 26th day he was able to stand up by himself in order to move into the chair. On the 30th day a percutaneous gastrostomy was done and he started on an individualized nutritional programme. On the 54th day the tracheostomy was closed.

The patient was discharged on the 73rd day, presenting a fluent speech with minor dysarthria and no ocular movement loss. He presented grade 4 muscle strength in both upper and lower limbs and he was able to stand up and walk helped by a 2nd person. (image 4).

Due to hospital policies, GQ1b antibodies were only collected 115 days after admission and the results were negative.

DISCUSSION

MFS is an acute, immune-mediated demyelinating polyneuropathy and usually self-limited.1,3 Its usual triad presentation is ophthalmoplegia, ataxia and areflexia and, less frequently, other neurologic symptoms such as extremity weakness.3 MFS is mostly associated with third, fourth and sixth cranial nerves dysfunction, but involvement of almost all other cranial nerves has been documented. Unlike the classic ascending neurologic pattern of Guillain-Barré Syndrome, neurological deficits follow a top down pattern in MFS, starting with diplopia caused by external opthalmoplegia.4

Its etiology can be associated with an autoimmune, infectious or neoplastic condition.3 A cross-reaction between peripheral nerve antigens and microbial/viral components through molecular mimicry is thought to drive the inflammatory process of MFS.1 Campylobacter jejuni and Haemophilus influenzae have been implicated the most in infection etiology. However, multiple others are also associated with it.4 Upper respiratory infection is the most commonly described prodromic entity, followed by gastrointestinal illness.4

The collection of clinical, radiological, immunological and electrophysiological results suggests MFS diagnosis. GQ1b IgG antibodies are most commonly associated with involvement of oculomotor nerves and are usually present in 85 to 90 percent of patients with MFS, but its absence does not rule out the disease completely.2,4,5 This test must be performed during the first four weeks of clinical course.6 The association of the clinical triad with the presence of GQ1b antibodies is highly specific of MFS.6 Electrophysiological studies reveal reduced or absent sensory responses without slowing of sensory conduction velocities.1

MFS treatment is based on adequate supportive care, pain control, respiratory support and immunotherapy with IVIG or plasmapheresis.1,2 MFS prognosis is usually good with case fatality of less than 5% and mean recovery times ranging between 8 to 12 weeks.1

Figura I

Patient at admission, showing left eyelid ptosis.

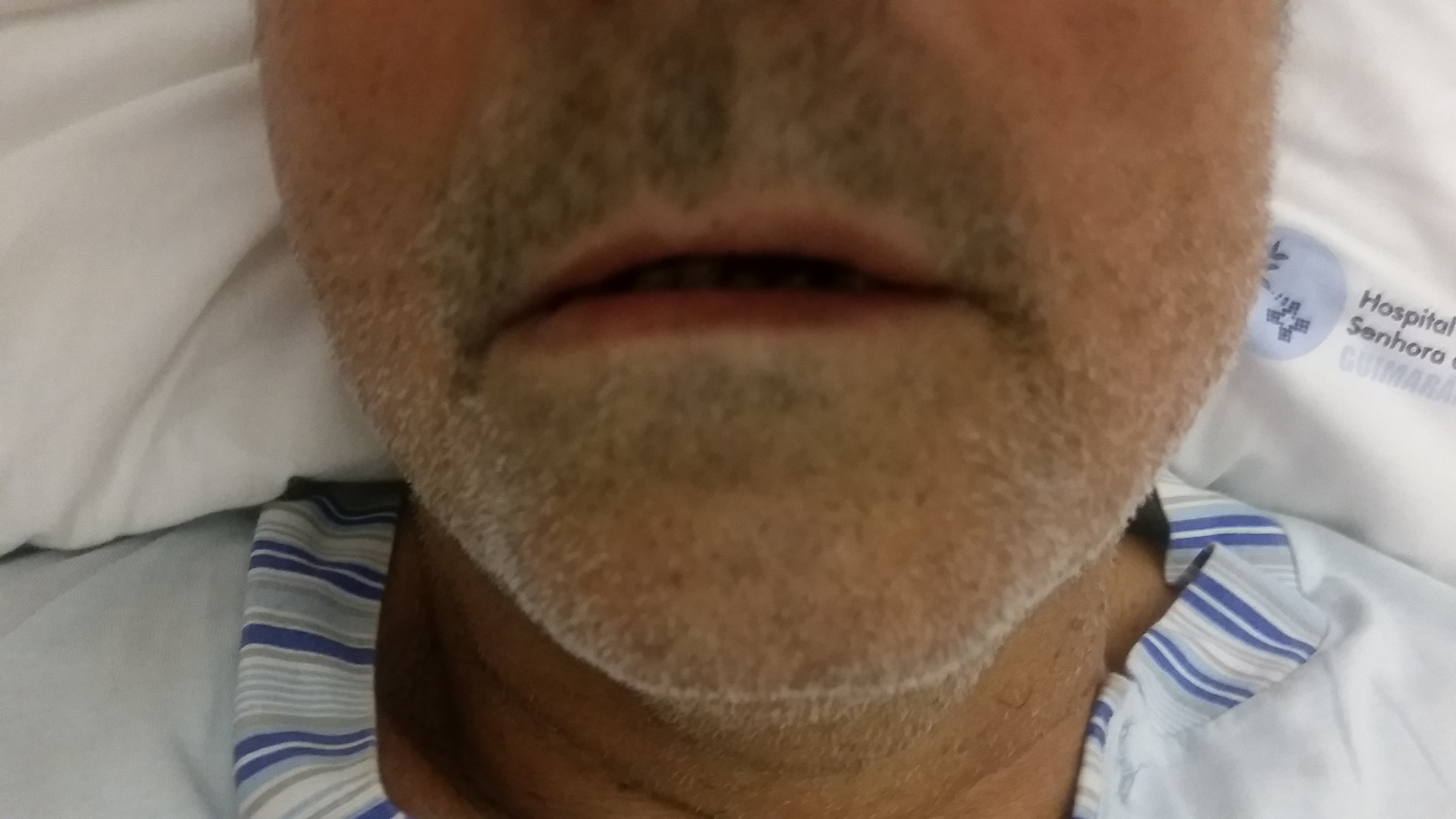

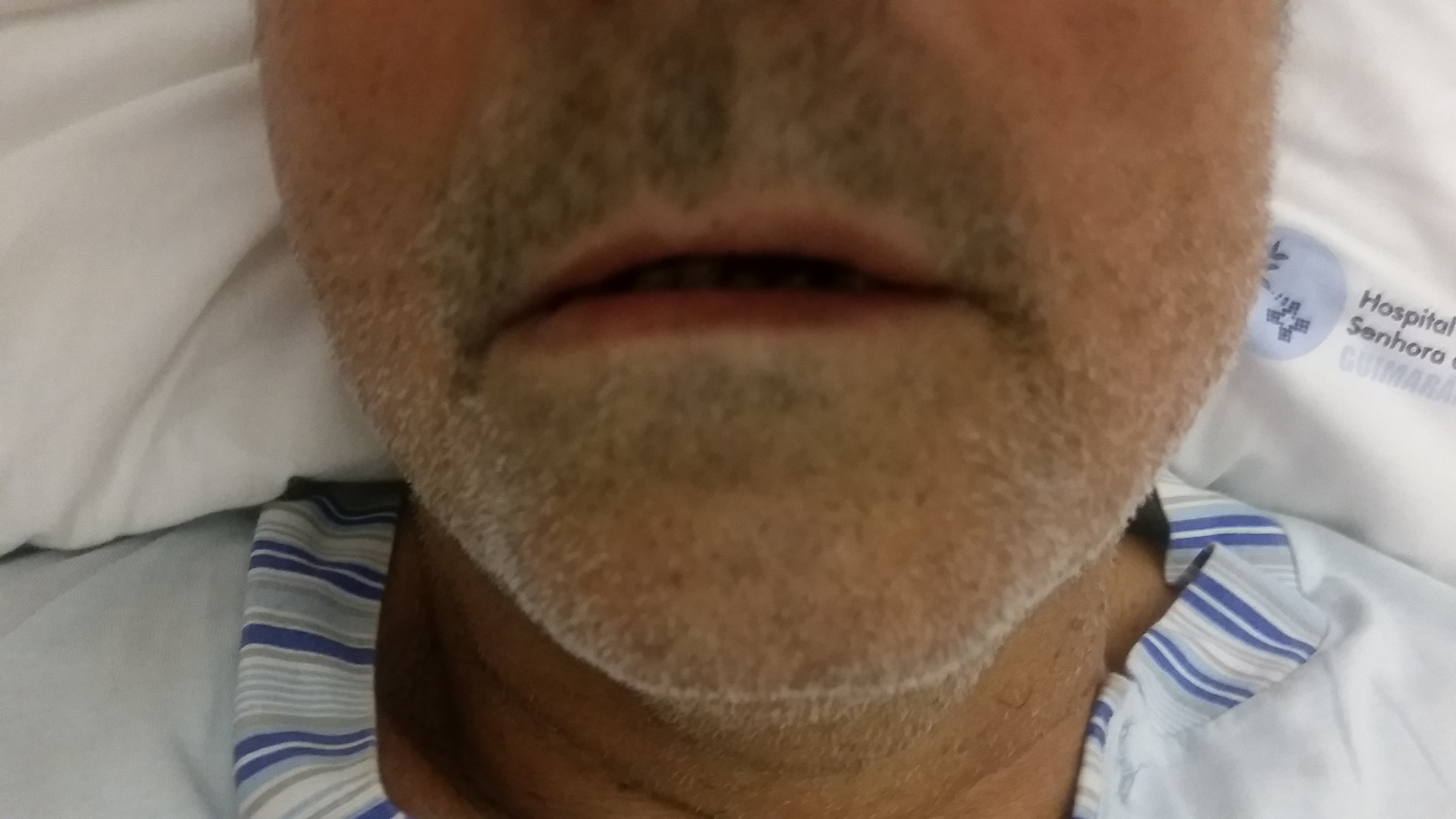

Figura II

Patient at admission, showing left facial paralysis.

Figura III

Patient with a tracheostomy, presenting bilateral facial paralysis and ophthalmoplegia.

Figura IV

Patient on the 73rd day, able to stand up and walk.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Rocha CF, Morrison EH. Miller Fisher Syndrome. [Updated 2019 Mar 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet], Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019.

2. Wijdicks EFM, Klein, CJ. Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Mayo Clin Proceedings. 2017 Mar;92(3):467-479. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.12.002.

3. Lo YL. Clinical and immunological spectrum of the Miller Fisher syndrome. Muscle Nerve 2007; 36:615.

4.Yepishin IV, Allison RZ, Kaminskas DA, Zagorski NM, Liow KK. Miller Fisher syndrome: a case report highlighting heterogeneity of clinical features and focused differential diagnosis. Hawaii J Med Public Health 2016;75:196–199.

5. Chiba A, Kusunoki S, Obata H, Machinami R, Kanazawa I. Serum anti-GQ1b IgG antibody is associated with ophthalmoplegia in Miller Fisher syndrome and Guillain-Barré syndrome: clinical and immunohistochemical studies. Neurology 1993; 43:1911.

6. Rojas-García R, Gallardo E, Serrano-Munuera C, de Luna N, Ortiz E, Roig C, et al. [Anti-GQ1b antibodies: usefulness of its detection for the diagnosis of Miller-Fisher syndrome]. Med Clin (Barc). 2001 Jun 2;116(20):761-4