INTRODUCTION:

Autoimmune diseases are among the most challenging conditions to diagnose because of their clinical heterogeneity2. NPSLE is associated with increased morbidity and mortality as it affects nearly half of the patients with SLE and ranges from mild diffuse to acute life-threatening events1-4. Severe central nervous system (CNS) involvement in SLE is uncommon and has an estimated prevalence of around 4%5. The pathogenesis of NPSLE is multifactorial and involves inflammatory cytokines and autoantibodies. Most of the clinical manifestations of disease are nonspecific complicating the diagnosis, clinical assessment, and treatment planning2.

CASE DESCRIPTION:

A 66-year-old caucasian man with no relevant past medical history and no habitual medications presents with a one-week history of unusual symptoms of insomnia, agitation, and anxiety. Drugs and alcohol were immediately excluded. Blood tests were only remarkable to a new onset thrombocytopenia (77.000/µl). After psychiatric evaluation, a benzodiazepine was prescribed, and he was discharged.

A week later he returns with the same psychiatric symptoms and a new onset oromandibular dyskinesia and was admitted for complementary study. The next day he showed disorganized speech and behaviour as well as visual hallucinations and was medicated with haloperidol and chlorpromazine with little success; later that day he initiated a very hard to manage choreic disorder leading to initiation of profound sedation and consequent endotracheal intubation for airway protection. Cranial CT scan showed no alterations and cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) had some nonspecific white-matter hyperintensities on T2 and FLAIR sequences at the frontal lobe. A cranial MRI angiography was performed showing enlargement of peripheral cerebrospinal fluid spaces compatible with cortical atrophy and small white-matter hyperintensities affecting the corona radiata and the centrum semiovale, suggestive of vasculopathy. An electroencephalogram was performed with no epileptiform activity. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies were mostly normal as there was only found 2 oligoclonal IgG bands, but albumin and IgG quotients were normal and anti-NDMA receptor antibody was negative. Neurotropic infectious pathogens were excluded and cultures were negative for bacteria and mycobacteria (Table 1). HIV types 1/2, HCV, HBV and treponemal test were negative. A thoracoabdominal-pelvic CT scan was also performed with no relevant changes. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 111 mm/hour. From the auto-immune study we highlight positive antinuclear antibodies (1:640) as well as strong postive antiphospholipid antibodies (aPA) – lupus anticoagulant, anti-cardiolipin antibody and anti-glycoprotein 2 antibody; there was also complement consumption (both C3 and C4) (Table 2). These tests were repeated after 12 weeks remaining positive.

SLE diagnosis was made based in the new European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria.

After initiating high dose pulse intravenous steroids with 1g of methylprednisolone given daily for three days our patient showed great improvement. He was later discharged with hydroxychloroquine, antiplatelet therapy and oral corticosteroid (prednisolone) that has been successfully tapered in follow-up appointments.

DISCUSSION:

SLE can affect the nervous system and some reports suggest that up to 63% of NPS may appear during first year of diagnosis6; however, it rarely presents as a neuropsychiatric syndrome.

NPSLE is one of the most complex and less understood aspects of SLE. The pathophysiology of NPSLE is considered a combination of autoantibody-mediated neuronal or vascular injury, intrathecal production of inflammatory cytokines, disruption of the blood brain barrier and accelerated atherosclerosis6.

Thirty to forty percent of SLE patients are tested positive for aPa as seen in our case report. SLE patients with positive aPa are about twice as likely as aPa-negative to develop NPSLE and thrombosis7-9. The fact that aPa positivity has been linked with NPSLE syndromes that are not causally related to thrombosis, such as seizures, chorea and cognitive dysfunction suggests that these autoantibodies have a pathogenic role beyond their prothrombotic effects10.

Although our patient did not have the typical CNS thrombotic alterations of antiphosholipid antibody syndrome (APS) (such as large territorial infarctions, lacunar infarctions in the deep white matter, localized cortical infarctions in the middle cerebral artery territory or anterior basal ganglia lesions)7,11 being triple positive aPa emphasizes that there is a significative risk of developing secondary APS.

NPSLE most frequent symptoms are headache, mood disorders, anxiety and mild cognitive dysfunction10,12.

Psychosis can affect up to 11% of SLE patients and has been related to high titres of anti-ribossomal P1,13 protein antibodies but in our case they were negative as seen in Table 2.

Movement disorders are one of the rarest manifestations and chorea is the most described movement disorder in SLE (1-4%)14. Chorea is associated with the presence of aPA in up to 92% of cases, as found in this report14. Some studies suggest that an altered metabolism or perfusion in the striatum, associated with positive aPA, may be the underlying mechanism of chorea on SLE14.

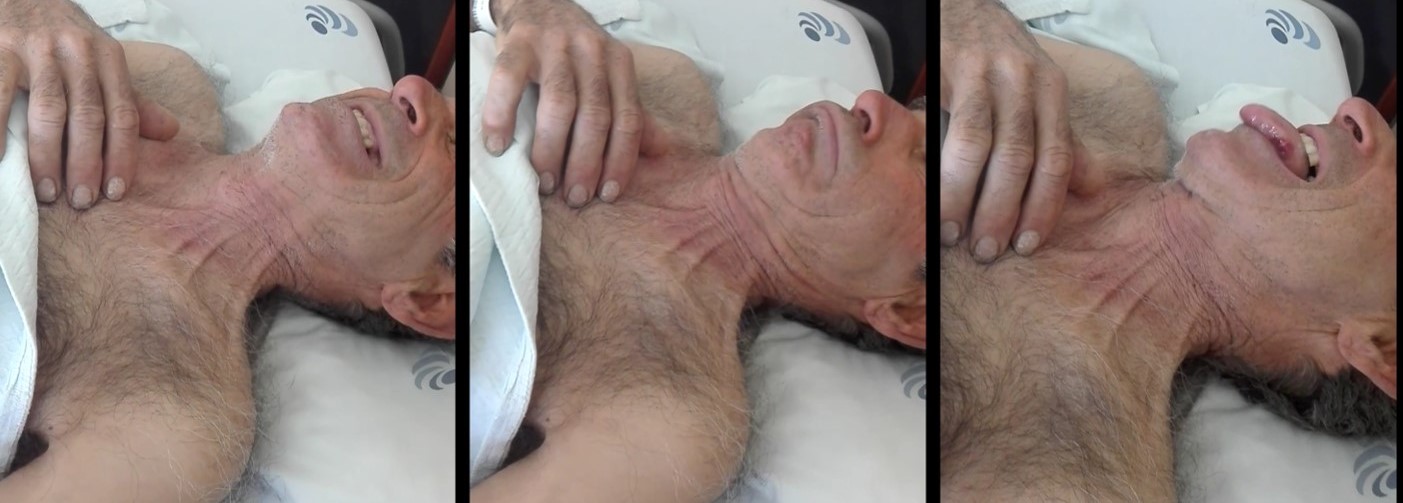

Oromandibular dyskinesia is an extremely rare manifestation of SLE and has only been described in a few cases of concomitant SLE and APS.

MRI is the gold standard for studying the brain in SLE but there are neither diagnostic nor specific radiological findings for NPSLE. The most common finding is small vessel disease particularly white-matter hyperintensities (preferentially at frontal and parietal lobes) followed by cortical atrophy as seen in our case report. The physiopathology of these lesions is not well understood but they are observed more frequently in NPSLE when compared with SLE without NPS, with average ranges from 40 to 60%, and are associated with poorer prognosis14-18.

Routine evaluation of the CSF may be normal in patients with CNS lupus, except in cases of aseptic meningitis, vasculitis, and transverse myelitis19. CSF abnormalities have been seen in 30-40% of patients SLE, and it is generally associated with a poor prognosis20. In a 10-year prospective study, sensitivity for a CSF triad (IgG index, oligoclonal bands and antineuronal and/or antiribosomal-P antibodies) was 100 percent for NPSLE, while specificity was 86 percent19,21. These tests appear to correlate with clinical responses to therapy19,21. Some SLE patients may have circulating antiNMDA receptor antibodies that can cause neuronal damage and memory deficits if the blood-brain barrier is breached22. In our case, there was no evidence of BBB disruption as albumin and IgG quotients were normal and anti-NMDA recepetor antibody was negative, but we found 2 oligoclonal IgG bands in CSF- analysis.

NPSLE treatment should be administered according to whether the NPS are attributable to a diffuse inflammatory syndrome or a focal thromboembolic process; glucocorticoids and if necessary immunosuppressive therapy such as cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate are indicated in the first and anticoagulation therapy is indicated when manifestations are related to antiphospholipid antibodies, particularly thrombotic cardiovascular disease23. Current recommendation is to treat patients with SLE who are seropositive to aPA with antiplatelet therapy as primary prevention, as was done in this case, while anticoagulants are reserved for secondary prevention1,4,12. For refractory NPSLE, intravenous immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis, and rituximab have been used. Adjunctive symptomatic treatment may be used targeting mood disorders and psychosis with antipsychotic agents like risperidone and olanzapine. Antidepressant and anxiolytic agents are indicated in patients with concomitant depressive or anxious symptoms.

CONCLUSION: We here present an extremely rare case of acute, complex, life threatening neuropsychiatric signs as first manifestations of SLE. Movement disorders are very uncommon and have been associated with the presence of aPA; chorea is the most described in SLE however we could not find reports in which chorea was only controllable with profound sedation. Oral dyskinesia is far rarer than chorea and we were unable to find any case reports of this sign as a first manifestation of SLE. Psychosis has been related to high titres of anti-ribossomal P antibodies but in our case we could not find this association. Compared with SLE patients without aPA, those with aPA have a higher prevalence of thrombosis, worse quality of life and higher risk of organ damage10,24,25.

Quadro I

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis

| IMMUNOLOGIC PROFILE | Serum albumin | 2770mg/dl | IgG quotient | 0,44 |

| Serum IgG | 815mg/dl | Potassium channels VGKC Ab | <5pmol/l | |

| - Normal albumin quotient | Serum IgA | 156mg/dl | Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor IgG Ab | Negative |

| * no barrier disorders | Serum IgM | 168mg/dl | Enterovirus RNA | Negative |

| CSF Albumin | 12,80mg/dl | Herpes simplex vírus typer 1/2 DNA | Negative | |

| - Oligoclonal bands analysis type 3 | CSF IgG | 1,67mg/dl | Varicella-zoster vírus DNA | Negative |

| * 2 IgG oligoclonal bands in CSF | CSF IgA | 0,16mg/dl | Cytomegalovirus DNA | Negative |

| * aditional bands iddentical in CSF and serum | CSF IgM | 0,04mg/dl | VDRL | Negative |

| * combination of types 2 and 4 | Albumin quotient | 0,0046 | Cultures for bactéria and mycobacteria | Negative |

Quadro II

Autoimmunity serum panel

| Antinuclear Ab | Positive (1:640, fine speckled, positive for anti-PL-12 and anti-SRP Ab) | Anti-B2-glicoprotein-1 IgG Ab | Strong positive (562UA/ml) | Antireticulin Ab | Negative |

| Anti-Sm, RNP. SSA/Ro52, SSB, Jo1, Scl70 Ab | Negatives | Anti-B2-glicoprotein-1 IgM Ab | Strong positive (70,2UA/ml) | Antiglicoprotein-210 Ab | Negative |

| Anti-dsDNA Ab | Negative | Anticardiolipin IgG Ab | Strong positive (600GPL/ml) | Anti-neuronal Ab (Hu, Yo, Ri, CV2, PNMA2) | Negatives |

| Lupic anticoagulant | Positive (1,24) | Anticardiolipin IgM Ab | Strong positive (68MPL/ml) | Antimithochondrial Ab | Negative |

| Anti-ribosomal P protein Ab | Negative | Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic Ab (cANCA/PR3) | Negative | Anticitrulin Ab | Negative |

Figura I

Oromandibular dyskinesia

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1 Kivity, S., Agmon-Levin, N., Zandman-Goddard, G., Chapman, J., & Shoenfeld, Y. (Mar de 2015). Neuropsychiatric lupus: a mosaic of clinical presentations. BMC Medicine.

2 Shoenfeld, Y., Cervera, R., & Gershwin, M. E. (2008). Diagnostic Criteria in Autoimmune Diseases. Humana Press.

3 Lisnevskaia, L., Murphy, G., & Isenberg, D. (2014). Systemic lupus eryhtematosus. The Lancet.

4Popescu, A., & Kao, A. H. (2011). Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Current Neuropharmacology, 9, 449-457.

5 Kampylafka, E. I., Alexopoulos, H., Kosmidis, M. L., Panagiotakos, D. B., Vlachoyiannopoulos, P. G., Dalakas, M. C., . . . Tzioufas, A. G. (2013). Incidence and Prevalence of Major Central Nervous System Involvement in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A 3-Year Prospective Study of 370 Patients. PLOS one.

6 Magro-Checa, C., Zirkzee, E. J., Huizinga, T. W., & Steup-Beekman, G. M. (2016). Management of Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Current Approaches and Future Perspectives. Drugs, 76, 549-483.

7 Mayer, M., Cerovec, M., Rados, M., & Cikes, N. (2010). Antiphospholipid syndrome and central nervous system. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery.

8 Espinosa, G., & Cervera, R. (2015). Current treatment of antiphospholipid syndrome: lights and shadows. Nature.

9 Ünlu, O., Erkan, D., & Zuily, S. (2016). The clinical significance of antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur J Rheumatol, 75-84.

10 Schwartz, N., Sotck, A. D., & Putterman, C. (2019). Neuropsychiatric lupus: new mechanistic insights and future treatment directions. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 15, 137-152.11 Fleetwood, T., Cantello, R., & Comi, C. (2018). Antiphospholipid Syndrome and the Neurologist: From Pathogenesis to Therapy. Frontiers in Neurology.

12 Jennekens, F. G., & Kater, L. (Jun de 2002). The central nervous system in systemic lupus erythematosus. Part 1. Clinical syndromes: a literature investigation. Rheumatology, 41(6), 605-618.

13 Briani, C., Lucchetta, M., & Ghirardello, A. (2009). Neurolupus is associated with anti-ribosomal P protein antibodies: An inception cohort study. Journal of Autoimmunity, 79-84.

14 Baizabal-Carvallo, J., Alonso-Juarez, M., & Koslowski, M. (2011, Mar). Chorea in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Rheumatol, 69-72

15 Sarbu, N., Bargalló, N., & Cervera, R. (2015). Advanced and Conventional Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Neuropsychiatric Lupus. F1000 Research.

16 Sarbu, N., Alobeidi, F., Toledano, P., Espinosa, G., Giles, I., Rahman, A., . . . Bargalló, N. (2015). Brain abnormalities in newly diagnosed neuropsychiatric lupus: systematic MRI approach and correlation with clinical and laboratory data in a large multicenter cohort. Autoimmun Rev, 153-9.

17 Ercan, E., Ingo, C., Tritanon, O., Magro-Checa, C., Smith, A., Smith, S., . . . Ronen, I. (May de 2015). A multimodal MRI approach to identify and characterize microstructural brain changes in neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Neuroimage Clin, 16(8), 337-44.

18 Luyendijk, J., Steens, S. C., Ouwendijk, W. J., Steup-Beekman, G. M., Bollen, E. E., van der Grond, J., . . . van Buchem, M. A. (2011). Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: lessons learned from magnetic resonance imaging. Arthiritis & Rheumatism, 722-732.

19 Schur, P. H. (Aug de 2020). Diagnostic approach to the neuropsychiatric manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. From UpToDate: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnostic-approach-to-the-neuropsychiatric-manifestations-of-systemic-lupus-erythematosus

20 Ramachandran, T. S. (Jul de 2018). CNS Lupus Workup. From Medscape: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1146456-workup

21 West SG, Emlen W, Wener MH, Kotzin BL. Neuropsychiatric lupus erythematosus: a 10-year prospective study on the value of diagnostic tests. Am J Med. 1995; 99(2):153–63.

22 Kowal C, DeGiorgio LA, Lee JY, et al. Human lupus autoantibodies against NMDA receptors mediate cognitive impairment.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.2006;103(52):19854–9.

23 Fanouriakis, A., Kostopoulou, M., Alunno, A., Aringer, M., Bajema, I., Boletis, J. N., . . . Kuhn, A. (2019). 2019 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. BMJ.

24 Moraes-Fontes, M., Lúcio, I., Santos, C., Campos, M., Riso, N., & Riscado, M. V. (2012). Neuropsychiatric Features of a Cohort of Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. ISRN Rheumatology.

25 Sanna, G., Bertolaccini, M. L., Cuadrado, M. J., Laing, H., Khamashta, M. A., Mathieu, A., & Hughes, G. R. (2002). Neuropsychiatric Manifestations in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Prevalence and Association with Antiphospholipid Antibodies. Journal of Rheumatology.