Introduction

Strongyloidiasis is a helminthic infection caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. This agent completes its life cycle in the human host.1 Strongyloidiasis is more frequent in rural areas of tropical and subtropical regions however some cases have already been reported in Europe.2 The parasite penetrates the skin and spreads via bloodstream to the lungs where it ascends into the tracheobronchial tree, being swallowed afterwards. The larvae grows inside duodenum and jejunum, where they can live for years, eventually being eliminated through stool. Larvae can also penetrate again to bloodstream through the intestinal mucosa and return to lungs (internal autoinfection) or by perianal skin (external autoinfection).3

The authors report an opportunistic Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection in an IgG4-related disease patient under glucocorticoids. Immunosuppression adverse effects are well described in literature. This report highlights the importance to include uncommon parasitic infections in differential diagnosis.

Case report

The authors report a 57-year old Caucasian male clinical case, diagnosed with IgG4-related disease four months before admission. The diagnosis was based on retroperitoneal fibrosis, ground glass pulmonary areas, increased inflammatory parameters as well as two histology results compatible with IgG4-related disease (lymph node excision and pulmonary biopsy). He started prednisolone 1mg/kg/day for eight weeks with progressive tapering down (30 mg/day at the admission time). His medical background also included type 2 diabetes mellitus (treated with insulin and gliflozin association), hypertension (non-pharmacological control) and dyslipidaemia (statin). He was alcohol abstinent but used to drink 50 g/day until nine months before admission. Living in a rural environment was the only epidemiologic factor identified. Never left his native country (Portugal).

The patient was admitted to the emergency room with one week evolution of abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, anorexia and constipation. On physical examination he had confused speech (Glasgow coma scale 14) and was pale, sweating excessively, hypothermic, tachypneic and tachycardic with normotension. The abdominal examination demonstrated diffuse moderate pain without peritoneal irritation signs. Lab results revealed serious metabolic acidemia (pH 6.99, HCO3- <3 mmol/L, pO2 144 mmHg, pCO2 9 mmHg, lactate 1.7 mmol/L), hyperglycaemia (414 mg/dL maximum), elevated inflammatory parameters (30.100 X 109/L white blood cells with 85% neutrophilia but without eosinophilia; C-reactive protein 159 mg/L), mild hyponatremia (sodium 132 mmol/L), serum creatinine 1.3 mg/dL and lactate dehydrogenase elevation (1224 U/L maximum). The abdominopelvic Computed Tomography (CT) identified diffuse colonic parietal thickening, more evident in the right hemicolon, suggesting a colitis phenomenon and excluding other aetiology and complications. Blood cultures were taken. Empiric broad spectrum antibiotic has been initiated (piperaciline/tazobactam), as well as volemic reposition, insulin and potassium supplementation.

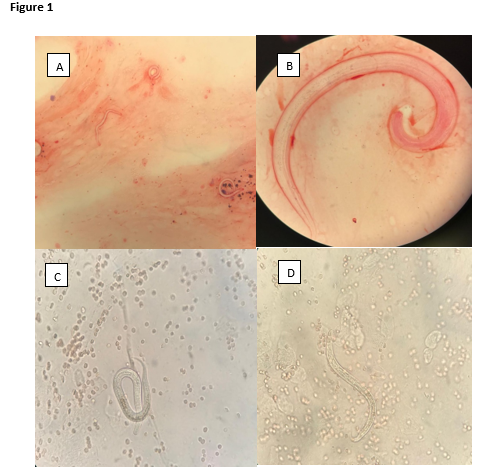

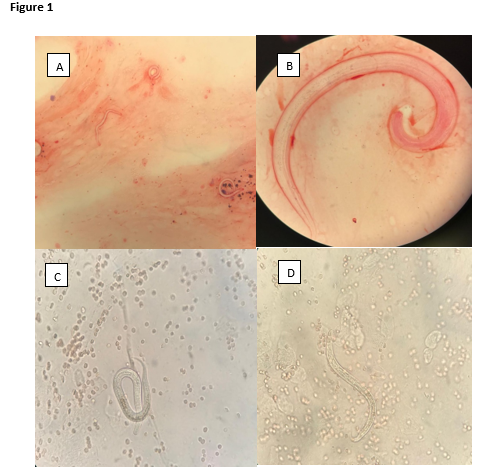

Nevertheless, he developed cutaneous abdominal vasculitic-like lesions and septic shock. The multiorgan dysfunction included: cardiocirculatory (norepinephrine maximum 0.35 ug/kg/min); respiratory (hemoptoic sputum and progressive worsening ratio - minimum PaO2/FiO2 = 115 and invasive mechanical ventilation need); hematologic (normocytic/normochromic anaemia and mild thrombocytopenia, performing two erythrocyte concentrate transfusion) and neurologic dysfunction (obtundation). Bloodstream cultures were positive to Escherichia coli and gastrointestinal tract origin assumed. Strongyloides stercoralis larvae were observed by microscope on sputum samples (see fig. 1). Severe hyperinfection by Strongyloides stercoralis became evident. Enteric albendazole was initiated (400 mg twice/day for four days) and ivermectin (15 mg/day) was associated two days later. Despite treatment, the patient´s clinical deteriorated and died two days later (UCI admission gravity scores SAPS II 18, APACHE II 18).

Discussion

We report Strongyloides opportunistic infection in an IgG4-related disease patient treated with corticoids, diabetic and with former alcoholic habits.

IgG4-related disease is a systemic disease characterized by immune-mediated fibroinflammation.4,5 It may present with various findings such as retroperitoneal fibrosis, autoimmune pancreatitis, cholangitis, salivary glands infiltration, lymphadenopathies and lung involvement. The diagnosis is defined upon the clinical, histopathologic, serologic and radiologic typical findings combination. Elevated serum IgG4 levels are common in 60-70% patients.5 Nonetheless, these are not specific findings. Some patients demand involved organ/lymph nodes tissue biopsy to exclude malignancy and other differential diagnosis. Immunosuppression is the treatment, with systemic corticosteroids as first option. Second line therapy includes rituximab or other immunosuppressive drugs.6

Corticoids have multiple anti-inflammatory, cellular and humoral immunosuppressive effects. They suppress macrophage differentiation and interleukin-1, interleukin-6, tumour necrosis factor and inhibition of proinflammatory prostaglandins and leukotrienes production.4 Corticosteroids disrupt the cellular immunity binding glucocorticoid receptors in the CD4+ T-helper type 2 cells (Th2), thus inducing their apoptosis or dysfunction.4,7Hence leadingto eosinophils under-recruitment, inhibiting macrophagic activity against the parasite and insufficient IgE antibodies production.7 Also, corticoidsinduce the production of ecdysteroid-like substances. These steroids regulate worm’s fecundity and act as molting signals for eggs and rhabditiform larvae, increasing the filariform larvae number and its dissemination.7

The patient’s past alcoholic habits may also have contributed to his Strongyloides hyperinfection risk. Alcohol ingestion modulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, increasing endogenous cortisol levels, contributing to the immune dysfunction mechanisms described above.7,8 Alcohol also reduces intestinal motility, allowing the rhabditiform larvae to stay in the gastrointestinal tract for a prolonged time, which allows them to transform in filariform larvae which can penetrate the bloodstream via intestinal mucosa (autoinfection).8

The previously described physiopathological pathways explain why this patient has more susceptibility to opportunistic Strongyloides infection. Immunocompromised patients have a higher Strongyloides hyperinfection risk by epidemiological exposure (even in a remote initial infection), but also by autoinfection (internal and external).9,10 The patient showed signs/symptoms compatible with multiorgan involvement, namely:

. Gastrointestinal tract: abdominal pain, constipation, anorexia, nausea/vomiting and radiologic bowel thickening in the absence of mechanical obstruction (common finding);

. Respiratory tract: hemoptoic sputum, fever and respiratory failure with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS);

. Skin: periumbilical vasculitic-like lesions, with extension to lower trunk and thighs;

All these symptoms/signs have been described in Strongyloidiasis hyperinfection syndrome.11

Reports show that the filariform larvae migration through the intestinal mucosa facilitates the enteric organisms’ entry to the bloodstream, which can explain the presence of E. Coli in the blood sample of our patient and may have contributed to the septic shock.12

In the development of hyperinfection/disseminated infection, peripheral eosinophilia is usually absent. This patient had no eosinophilia in admission and during all the episode, possibly related to Th2 dysfunction due to corticosteroid treatment and concomitant bacterial infection.7,13

Our patient died in the 14th day, confirming the poor prognosis described in the Strongyloides hyperinfection (mortality rate up to 70%).14,15

This case report highlights the importance of being suspicious about helminthic infection in septic immunocompromised patients. A full clinical history with special attention to the immunosuppressive risk factors and previous epidemiologic background is essential. Strongyloides chronic or acute infection in patients with bacteraemia may impose serious diagnosing difficulties to the clinician. Strongyloides infection may be latent and asymptomatic for years and turn into a life-threatening condition many years later, under immunosuppression conditions. Some studies report benefits in performing prophylactic treatment to a chronic infected patient, who will initiate immunosuppressive treatments.11

Figura I

Figure 1: A and B - Strongyloides stercoralis filariform larvae obtained from sputum observed with Gram stain at 100X and 1000X; C and D - Strongyloides stercoralis filariform larvae microscopically observed in a fresh sputum preparation (400X).

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Thomas B.N. Human infection with Strongyloides stercoralis and other related Strongyloides species. Parasitology. 2017;144(3):263–273.

2. Requena-Méndez A., Buonfrate D., Gomez-Junyent J., Zammarchi L., Bisoffi Z., Muñoz J. Evidence-Based Guidelines for Screening and Management of Strongyloidiasis in Non-Endemic Countries. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97(3):645.

3. Greaves D., Coogle S,. Pollar C., Aliyu S.H., Moore E.M. Strongyloides stercoralis infection. BMJ 2013;347:4610

4. Boumpas D.T., Chrousos G.P., Wilder R.L., Cupps T.R., Balow J.E. Glucocorticoid therapy for immune-mediated diseases: Basic and clinical correlates. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(12):1198–1208.

5. Kamisawa T., Zen Y., Pillai S., Stone J.H. IgG4-related disease. Lancet. 2015;385(9976):1460-71.

6. Khosroshahi A., Wallace Z.S., Crowe J.L., Akamizu T., Azumi A. et al. International Consensus Guidance Statement on the Management and Treatment of IgG4-Related Disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(7):1688.

7. Vasquez-Rios G., Pineda-Reyes R., Pineda-Reyes J., Marin R., Ruiz E., Terashima A. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome: a deeper understanding of a neglected disease. J Parasit Dis (Apr-June 2019) 43(2):167–175

8. Teixeira M., Pacheco F., Souza J., Silva M., Inês E., Soares N. Strongyloides stercoralis infection in alcoholic patients. Biomed Res Int 2016:4872473

9. Judd A., Jenni A., Richard S.B. The Unique Life Cycle of Strongyloides stercoralis and Implications for Public Health Action. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2018;3(2):53.

10. Schär F., Trostdorf U., Giardina F., Khieu V., Muth S., Marti H. et al. Strongyloides stercoralis: Global Distribution and Risk Factors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(7):e2288.

11. Santana A., Loureiro M. Síndrome de hiperinfecção e/ou disseminação por

Strongyloides stercoralis em pacientes imunodeprimidos. Rev Bras Anal Clin. 2017;49(4):351-8

12. Ghoshal U.C., Ghoshal U., Jain M., Kumar A., Aggarwal R., Misra A. et al. Strongyloides stercoralis infestation associated with septicemia due to intestinal transmural migration of bacteria. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17(12):1331.

13. Osiro S., Hamula C., Glaser A., Rana M., Dunn D. A case of Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome in the setting of persistent eosinophilia but negative serology. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;88(2):168.

14. Lam C.S., Tong M.K., Chan K.M., Siu Y.P. Disseminated strongyloidiasis: a retrospective study of clinical course and outcome. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;25(1):14.

15. Krolewiecki A., Nutman T.B. Strongyloidiasis: A Neglected Tropical Disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33(1):135-151.