BACKGROUND

Adverse drug reactions can occur as a complication of pharmacological therapy. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a rare severe cutaneous adverse reaction (SCARs) with an incidence of one to ten cases per million per year1,2 and a mortality of 4%.1,3 It is more common in women.4

A type IVd hypersensitivity reaction underlies its pathophysiology. After exposure to the culprit agent, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are activated. Drug-specific CD8+ T cells secrete perforin and granzyme B which induce the apoptosis of keratinocytes within the epidermis, leading to tissue destruction and vesicle formation.1,5 Furthermore, through secretion of CXCL8, drug-specific CD4+ T cells promote the recruitment of neutrophils to those epidermal vesicles, transforming it into sterile pustules.1,5

The most commonly associated agents are aminopenicillins, cephalosporins, quinolones, hydroxychloroquine, sulphonamides, terbinafine, diltiazem, and fluconazole.3,5 Although more than 90% of AGEP cases are drug-induced, other causes such as Parvovirus B19, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Cytomegalovirus infections, have also been implied.4–8

CASE REPORT

A 68-year-old woman, with a past medical history significant only for type 2 diabetes mellitus, and no known drug allergy history, was admitted to the Internal Medicine ward with a soft tissue infection of the right foot. On the first day of hospitalization, empiric treatment was started with piperacillin-tazobactam and kept for seven days. On the sixth day, metamizole was initiated for pain control and, on the seventh day, risperidone and paroxetine were introduced due to psychomotor agitation and mood disorder.

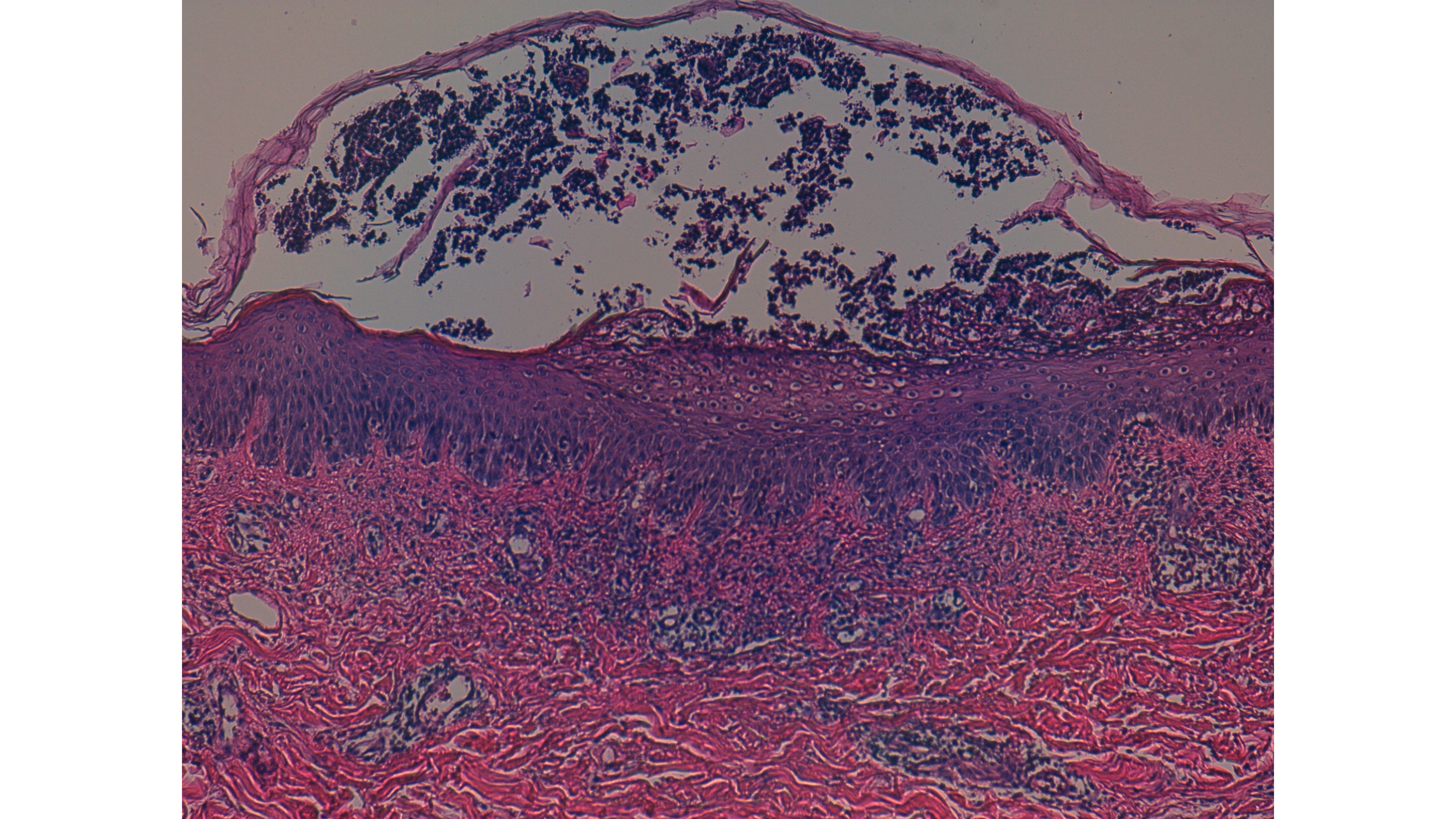

On the ninth day of hospitalization, the patient suddenly developed a symmetric and bilateral generalized pruritic dermatosis (Fig. 1 and 2), characterized by hundreds of non-follicular pinhead-sized pustules on a widespread edematous and erythematous maculopapular exanthem initially affecting the trunk, spreading to the neck, upper limbs, and armpits a few hours later. Mucous membranes and skin appendages were not affected and no adenopathies were found.

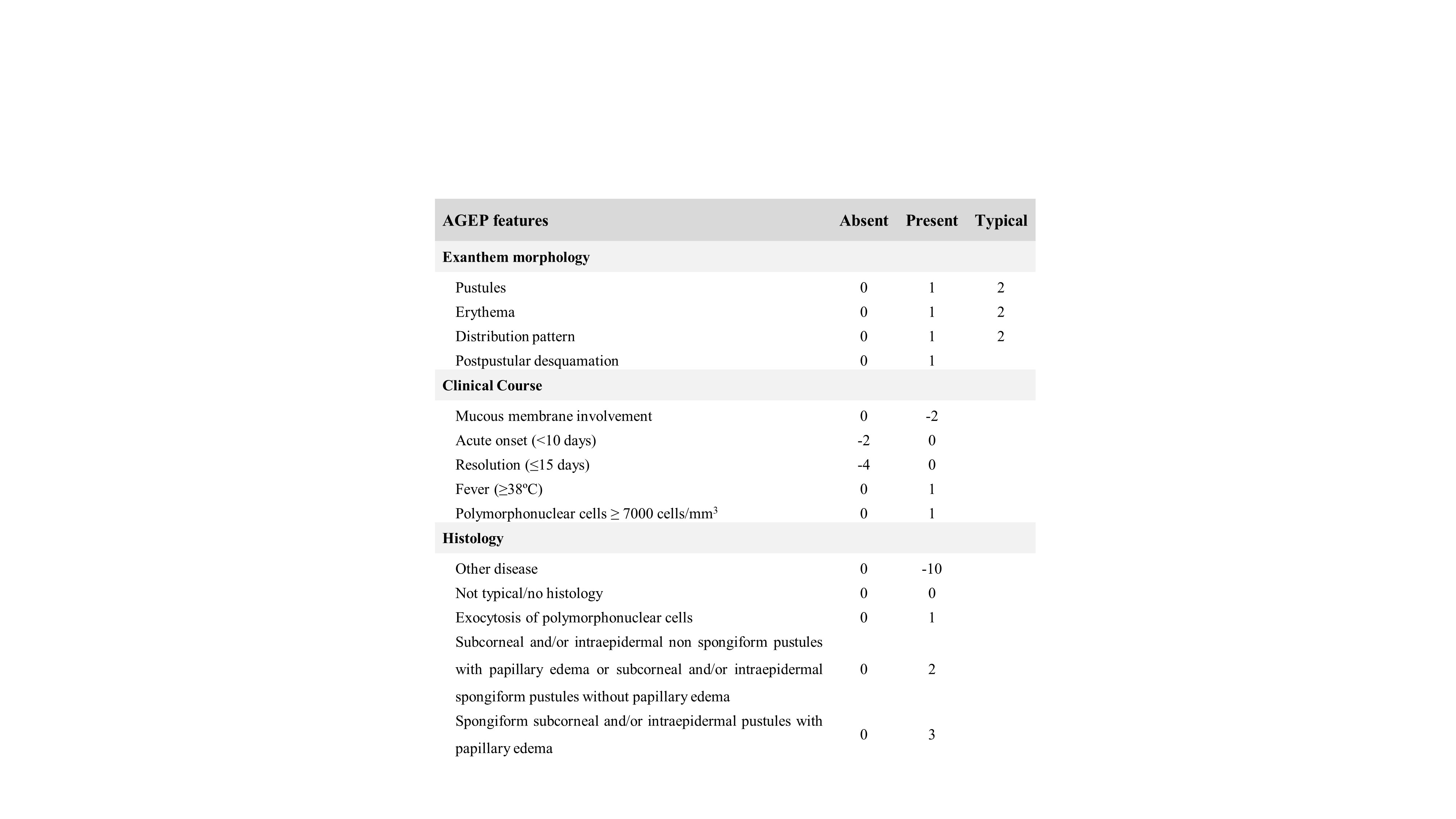

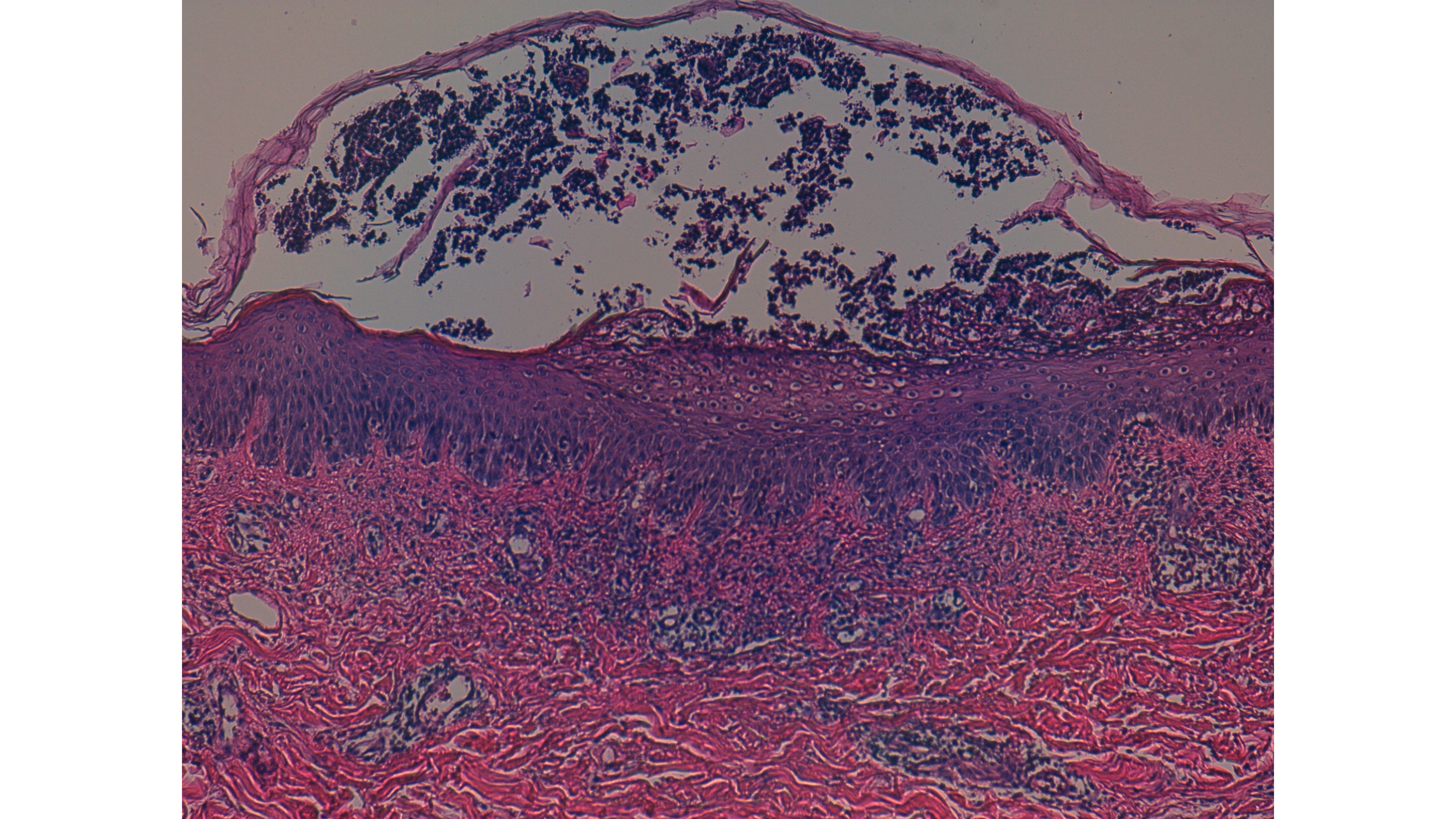

Meanwhile, she developed fever (38ºC) and blood tests revealed leucocytosis (14.7 x 109/L) with neutrophilia (91.7%), and a normal eosinophil count (0.01 x 109/L). Renal function and liver tests were within the reference values. Acute infection due to Parvovirus B19, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and human immunodeficiency virus were excluded. Blood cultures were negative. The diagnostic hypothesis of a drug hypersensitivity reaction, manifested either as AGEP or Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS), was considered, and the most likely involved drugs taken at that time, by temporal association, metamizole, risperidone and paroxetine, were suspended. We also considered pustular psoriasis as a differential diagnosis. Topical betamethasone, oral prednisolone, and oral H1 antihistamines were started. On the thirteenth day of hospitalization (4 days after the reaction’s onset), a 4 mm punch skin biopsy was performed intercepting one of the pustules. The patient presented with a good evolution, with progressive regression of the rash. Skin desquamation (Fig. 3) occurred four days after the exanthem started and complete lesion resolution took eleven days. The white cells count returned to baseline values after two days. Histological results (Fig. 4) showed an epidermis with extensive subcorneal pustules with papillary edema and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the superficial, perivascular, and interstitial dermis, with lymphocytes, neutrophils, and some eosinophils, compatible with AGEP. In the meantime, due to clinical necessity, paroxetine was reintroduced under vigilance without any clinical reaction.

Two months after complete resolution of the adverse reaction, the etiological investigation was carried out with drug epicutaneous tests in petrolatum (piperacillin-tazobactam at a concentration of 10%, 20%, and 100%; metamizole at 10%, 20%, and 50%; risperidone at 10% and 20%). Readings at 48 hours, 72 hours, and on day 7 were negative. The patient was then advised to continue the investigation with intradermal tests with late readings and/or lymphocyte transformation test (LTT), which she refused and was then advised to avoid all beta-lactams, metamizole, and benzisoxazoles.

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of AGEP depends on a combination of clinical and histological criteria. It is characterized by the acute appearance of numerous nonfollicular sterile pustules on a widespread pruritic erythematous exanthem, most frequently involving the neck, trunk, and intertriginous regions.1,3,5,9 The mucous membranes are rarely affected and, if so, only to a mild extent. Leukocytosis with neutrophilia and fever are typical. In about 20% of cases, there is systemic involvement with hepatic, renal, and/or respiratory insufficiency.3,5 The reaction usually develops after 1‐2 days for antibiotics but it could take longer, especially for other drugs (up to 11 days).3,9 It is histologically characterized by intracorneal, subcorneal, and/or intraepidermal pustules with papillary dermal edema and perivascular infiltrates containing neutrophils and eosinophils.1,5,9

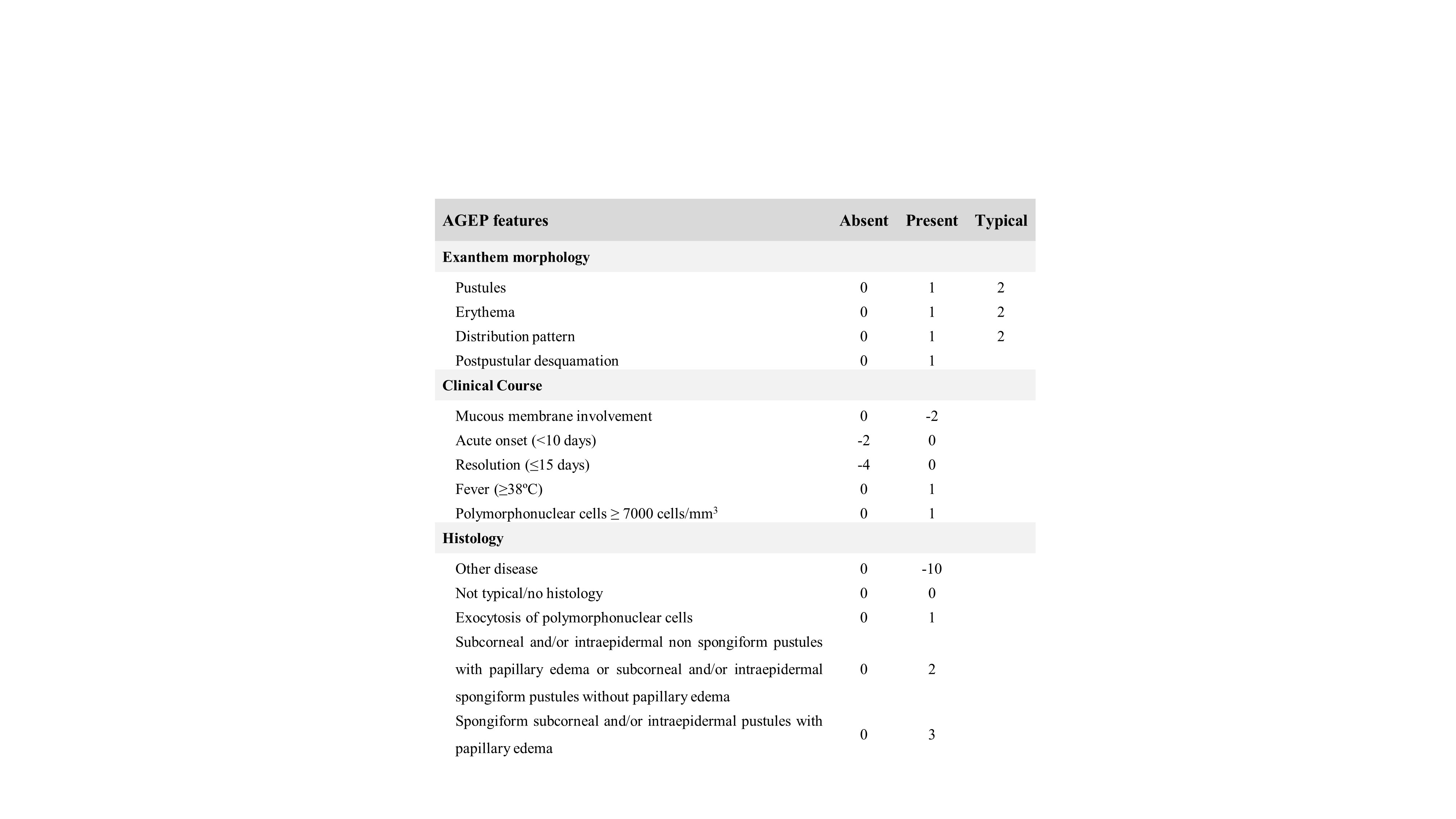

A score developed by the EuroSCAR group (Table 1) classifies suspected patients as having a definitive (8–12 points), probable (5–7 points), possible (1–4 points), or no AGEP diagnosis (<1 points).8 This score, which ranges from -24 to 12, considers the rash morphology, clinical course, and histology. In this case, even before the result of the cutaneous biopsy, the patient already had a score of 8 points (definitive diagnosis), which increased to 11 points after histological diagnosis confirmation and complete resolution of the reaction. AGEP’s main differential diagnoses are pustular psoriasis, DRESS, Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN).5 Pustular psoriasis has a more gradual onset and there is often a personal or family history of psoriasis, what was not the case of our patient. DRESS syndrome usually presents with a morbilliform rash but sometimes pustules can also be found; however, it is associated with a longer latent period of two to six weeks. In addition, in DRESS syndrome eosinophilia is common, adenopathies are more frequent and there is a systemic involvement in about 90% of cases (most commonly hepatitis, but also nephritis, pneumonitis, colitis, pancreatitis or arthritis). It may be difficult to distinguish SJS/TEN from severe cases of AGEP, especially in the rare cases with mucous membrane involvement; however, histologic features are distinct (full-thickness epidermal necrosis with a lymphocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction) from those we found in our case.5 So, we considered AGEP to be the most probable diagnosis.

In the management of AGEP, the most important measure is to identify and discontinue the causative agent. Topical corticosteroids are recommended for symptomatic relief of pruritus, and in some studies, they have been associated with a decrease of hospitalization length.5 The role of systemic corticosteroids in reducing the disease duration is unclear.5 Resolution of the eruption is associated with a typical postpustular desquamation and emollients are beneficial at this stage.3,9

Etiological investigation of AGEP culprit drug includes patch testing, intradermal tests with late readings and/or LTT.10,11 In our case, the patch tests performed were negative. However, considering its low sensitivity in SCARs,10,11 the negative result cannot exclude the involvement of the tested drugs. Intradermal tests with late readings and/or LTT were proposed, due to their higher sensitivity.10

We describe a drug induced AGEP. Despite not being the most frequent presentation, we consider the most probable drug to be piperacillin/tazobactam. Besides, we do not exclude metamizole or risperidone as culprits, albeit rarely associated drugs. To our knowledge, there is only one reported case of metamizole-induced AGEP and none due to risperidone.12

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Alexandre João, MD, for his contribution on the histological analysis, and Joana Pita, MD, for her support in the preparation of the patch tests.

CONSENT

A written informed consent was obtained from the patient described in this case report.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare the absence of economic or other types of conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

The manuscript did not receive funding.

Figura

Table 1: Diagnostic score for acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis from EuroSCAR study. No AGEP case (<1 points), possible case (1–4 points), probable case (5–7 points), definitive case (8–12 points)

Figura I

Figure 1: Nonfollicular sterile pustules on a widespread edematous and erythematous exanthem in the trunk.

Figura II

Figure 2: Nonfollicular sterile pustules on a widespread edematous and erythematous exanthem in an intertriginous area.

Figura III

Figure 3: Progressive resolution of the eruption with postpustular desquamation of the trunk. A gauze lining the area of the 4 mm skin punch biopsy is showed.

Figura IV

Figure 4: Skin biopsy (100x magnification).

BIBLIOGRAFIA

REFERENCES

1. Bellón T. Mechanisms of Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions: Recent Advances. Drug Saf. 2019;42(8):973–92.

2. Kyriakou A, Zagalioti S-C, Patsatsi A, Galanis N, Lazaridou E. Piperacillin/Tazobactam as Cause of Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis. Case Rep Dermatol Med.2019;2019:1–3.

3. Brockow K, Ardern‐Jones MR, Mockenhaupt M, Aberer W, Barbaud A, Caubet J, et al. EAACI position paper on how to classify cutaneous manifestations of drug hypersensitivity. Allergy. 2019;74(1):14–27.

4. Maren Paulmann,, Maja Mockenhaupt. Severe drug-induced skin reactions: clinical features, diagnosis, etiology, and therapy. Journal of the German Society of Dermatology. 2015;13(7):625–43.

5. Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): A review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5):843–8.

6. Conforti C, Meo N, Giuffrida R, Retrosi C, Vezzoni R, Romita P, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) caused by propafenone: an emerging skin adverse reaction. Dermatol Ther. Published online May 15, 2020

7. Chaucer B, Stone A, Whelan D, Demanes A, Fischer JL. AGEP from a dog bite treated with Ibuprofen. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(10):1927.e1-1927.e2.

8. Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Bavinck JNB, Vaillant L, Roujeau J-C. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) - A clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28(3):113–9.

9. Ardern-Jones MR, Mockenhaupt M. Making a diagnosis in severe cutaneous drug hypersensitivity reactions: Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immuno. 2019;19(4):283–93.

10. Mirakian R, Ewan PW, Durham SR, Youlten LJF, Dugué P, Friedmann PS, et al. BSACI guidelines for the management of drug allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39(1):43–61.

11. Pinho A, Coutinho I, Gameiro A, Gouveia M, Gonçalo M. Patch testing - a valuable tool for investigating non-immediate cutaneous adverse drug reactions to antibiotics. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(2):280–7.

12. M. Angeles Gonzalo-Garijo, Remedios Pérez-Caldero, Diego De Argila, Isabel Rodríguez-Nevado. Metamizole-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Contact Derm. 2003;49(1):42–42.