INTRODUCTION:

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a spontaneous or stimulus-induced chronic disorder characterized by pain, swelling, limited range of motion, autonomic symptoms, skin changes and bone loss in the affected region. 1 CRPS is more common in women and most frequently caused by fractures, crush injuries, sprains and orthopedic surgeries, particularly hand, foot or ankle surgery.2,3 The onset of CRPS generally occurs within four to six weeks of the trigger. 4 Typically, CRPS affects only one body region, most commonly an upper limb.5 There are two types of CRPS: type I, corresponding to patients without confirmed peripheral nerve injury; and type II or “causalgia”, when there is an established nerve damage. 6 Previously, CRPS was also known as Sudeck’s atrophy, algodystrophy, reflex neurovascular dystrophy or reflex sympathetic dystrophy.1,6,7

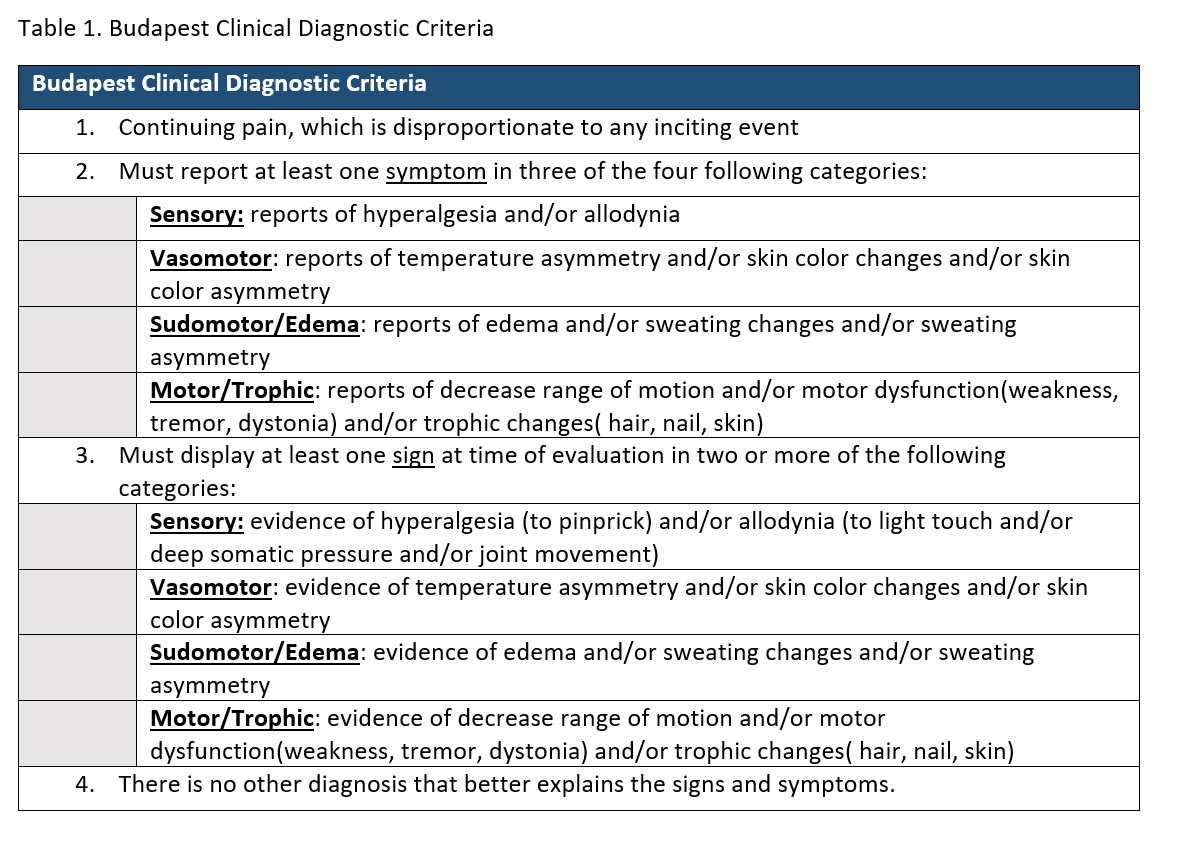

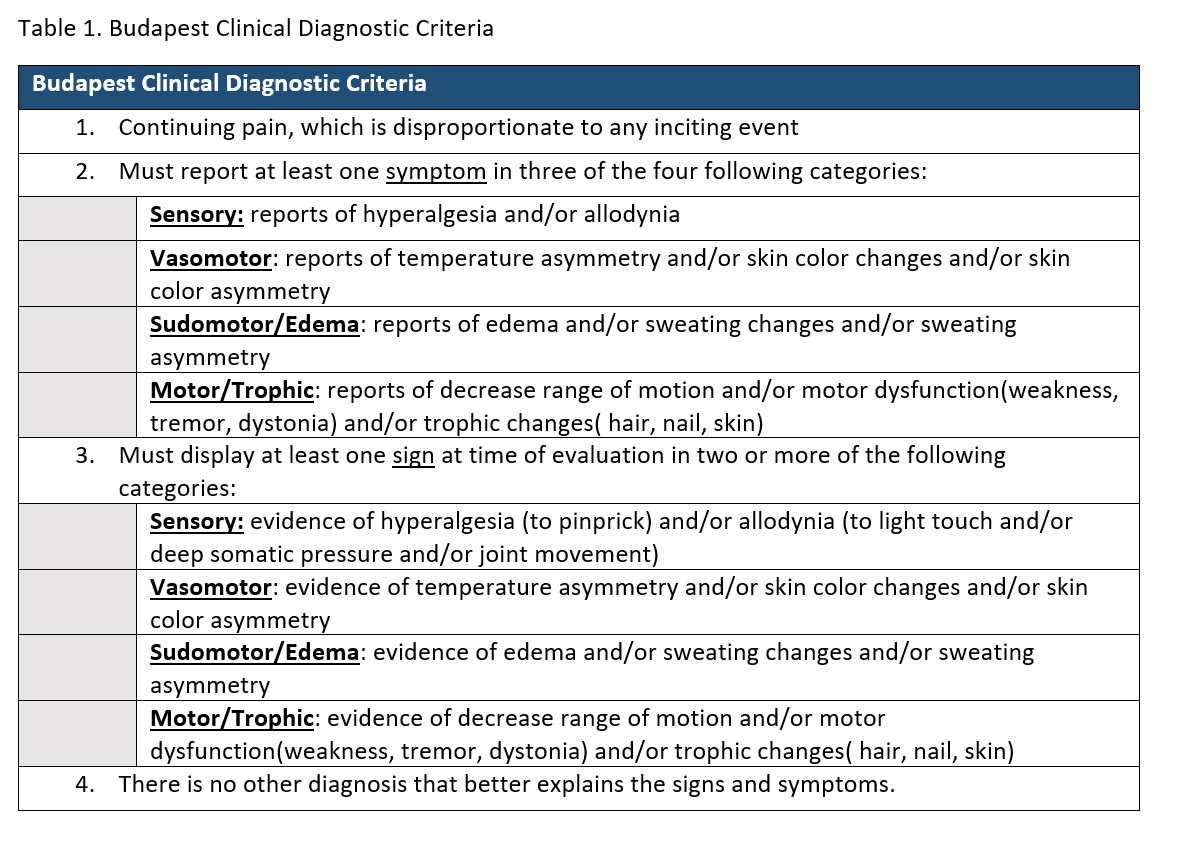

There is a recent agreement that CRPS is caused by a multifactorial process that involves both peripheral and central nervous systems. However, pathophysiological mechanisms are difficult to clarify, considering the heterogeneity of signs and symptoms. Proposed mechanisms include inflammation, altered cutaneous innervation, excessive sympathetic nervous system activation, changes in catecholaminergic actions, autoimmunity, brain plasticity, genetic factors, psychological influence and malignancy.7 There is no gold-standard test to confirm the diagnosis and, consequently, there are several diagnostic criteria. Nevertheless, the Budapest criteria (Table 1) seem to be equally sensitive and more specific when compared with others.4 A multidisciplinary approach is suggested for managing CRPS, with physical and occupational therapy, psychological therapy and symptomatic pain management. Clinical experience suggests that treatment is more effective when begun early in the course of the disease.8

This report describes a severe case of CRPS with affection of the four limbs, which had a late diagnosis in our clinic. Due to its unusual presentation involving multiple systems, we believe that this is an important example of the heterogeneity of pathologies without diagnosis that can appear in our clinics. Our aim is to highlight the role of the internist in the diagnosis and, to describe a very rare case of CRPS with an atypical presentation, both after vertebral spine surgery and with immediate affection of the 4 limbs, which may have contributed to late diagnosis and high morbidity.

CASE DESCRIPTION:

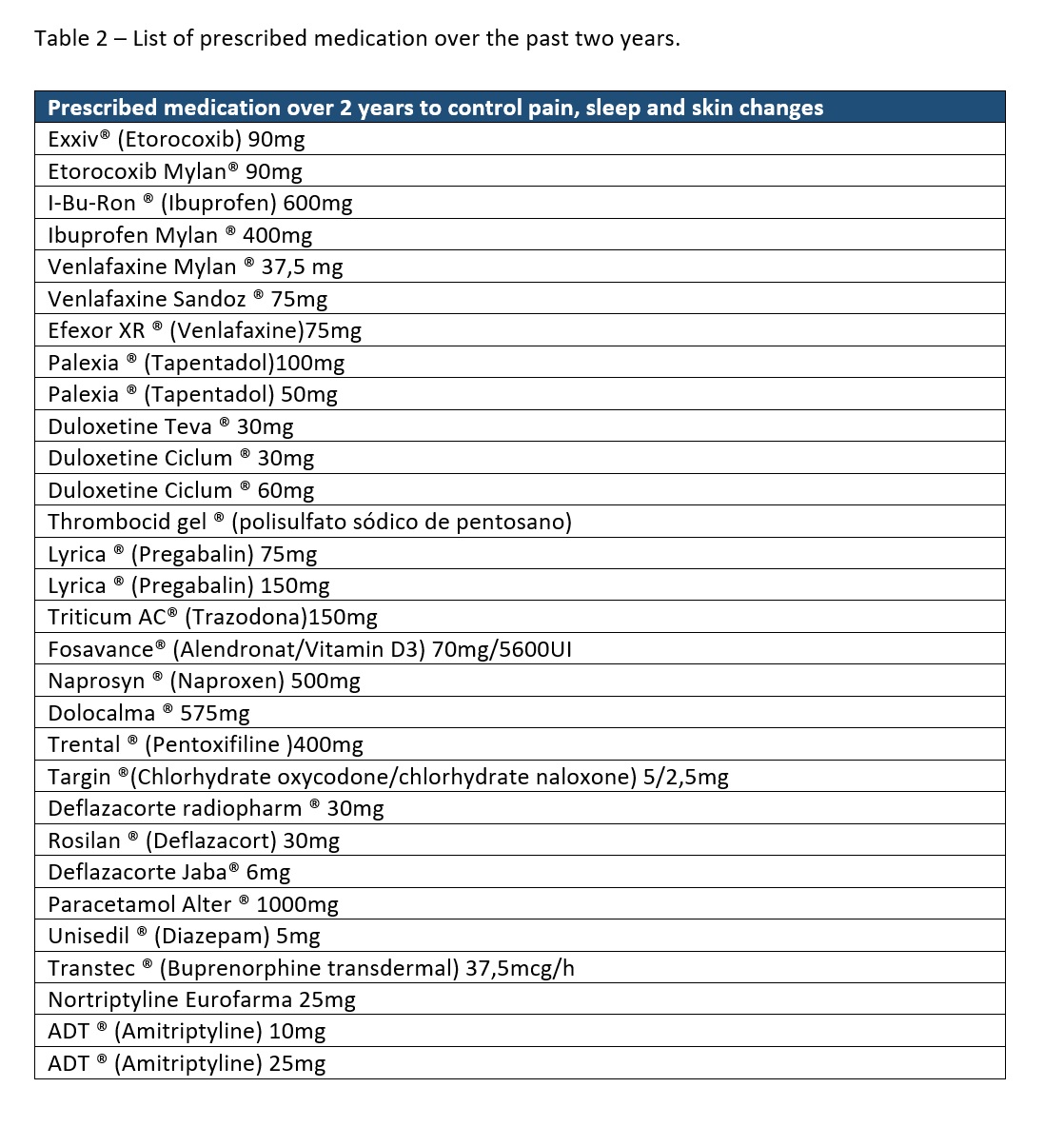

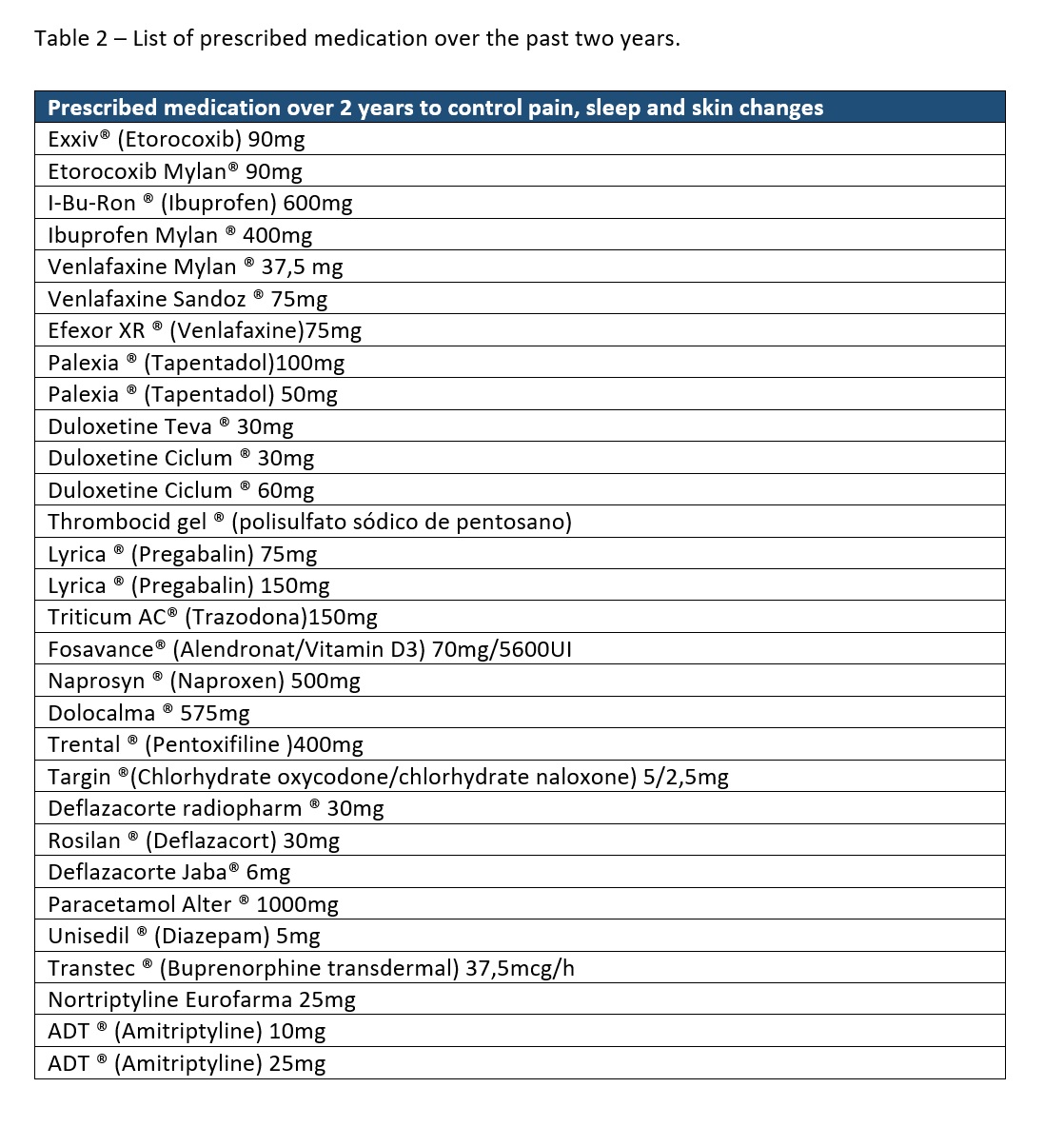

We describe a 51-years-old woman who arrived at our internal medicine clinic with excruciating pain, which began two years earlier and had progressively disabled her. The patient was being studied by six specialties, including neurology, neurosurgery, psychiatry, family medicine, rheumatology and cardiology. Moreover, she had thirty different prescriptions for symptomatic management, without pain control or definite diagnosis (Table 2).

Personal history included epilepsy since 18-years-old, secondary to cranio-encephalic trauma, and hypertension since the age of 40 years, while the only previous surgery was a C5-C6 hernia discectomy two years earlier. The patient was medicated with losartan 100mg, topiramate 25mg, naproxen 500mg twice daily and pregabalin 300mg twice daily and had a documented penicillin allergy, without relevant family background.

Symptoms included pain in the cervical, dorsal and lumbar spine, with irradiation to the four limbs. Pain was described as burning, stinging and tearing sensation, and exacerbated with limb movement, touch and at night. Neurologic examination revealed hyperalgesia and hyperesthesia in stocking and glove pattern, decreased muscle strength (4/5 in four limbs) and limb movement reduction due to pain and edema, without ataxia and with preserved neurologic reflexes. Autonomic symptoms included colder hands and feet, with redness and edema and episodes of increased sweating described by the patient. Physical examination reported atrophic skin and contracted joints, particularly elbows and knees. These alterations motivated many falls with trauma, leading to a high rate of urgency admissions. The patient denied other symptoms, such as arthritis, xerostomia, xerophthalmia, alopecia, history of thrombosis, rash, chest pain, mouth or genital ulcers, and other respiratory, gastrointestinal or genitourinary symptoms.

According to the patient, symptoms began on the immediate post-operative of a C5-C6 discectomy, two years previously, with progressive worsening and numerous prescriptions causing adverse effects, most frequently nausea, fever and diarrhea. The patient reported intolerance to duloxetine, tapentadol, etoricoxib, deflazacort and amitriptyline.

These prolonged incapacitating symptoms, mainly uncontrolled pain, and absence of a diagnosis, lead this patient to a major depression with suicidal ideation.

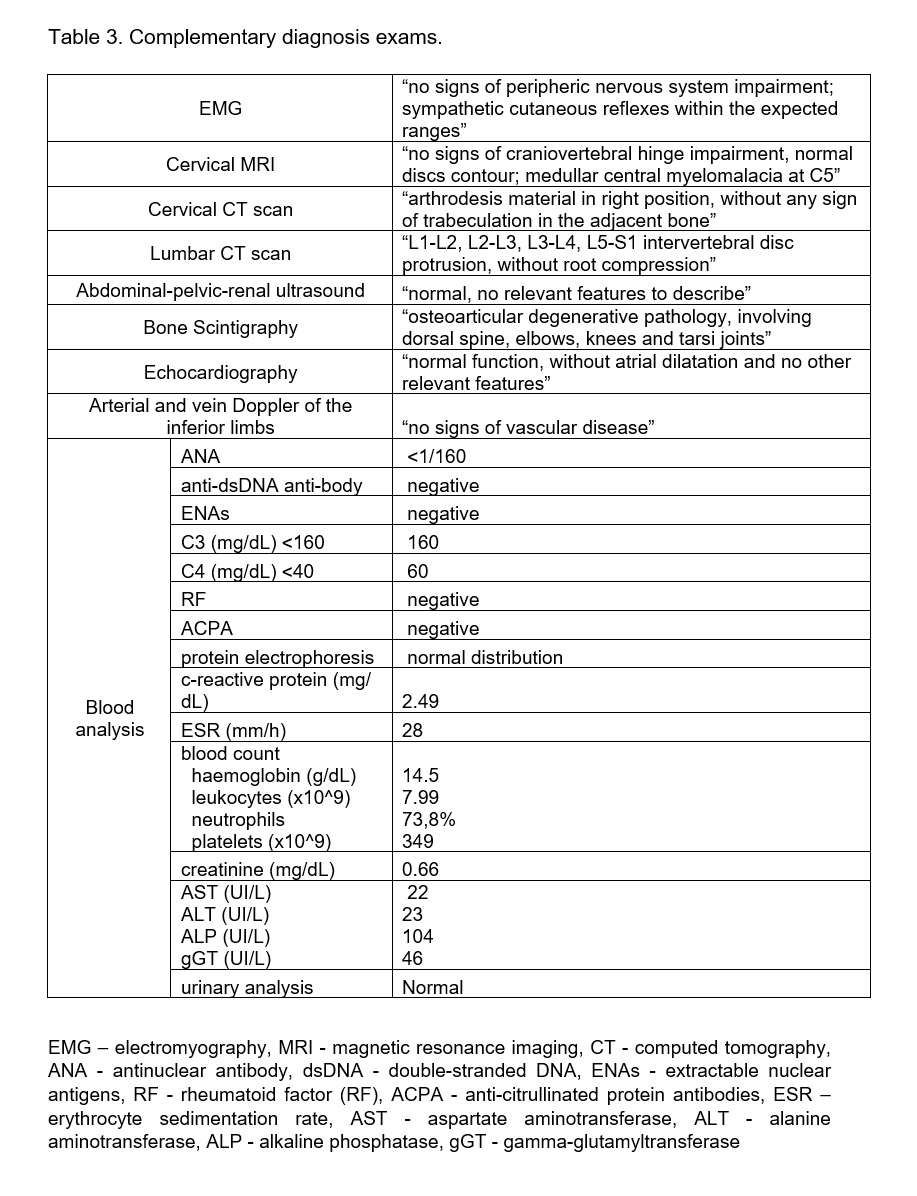

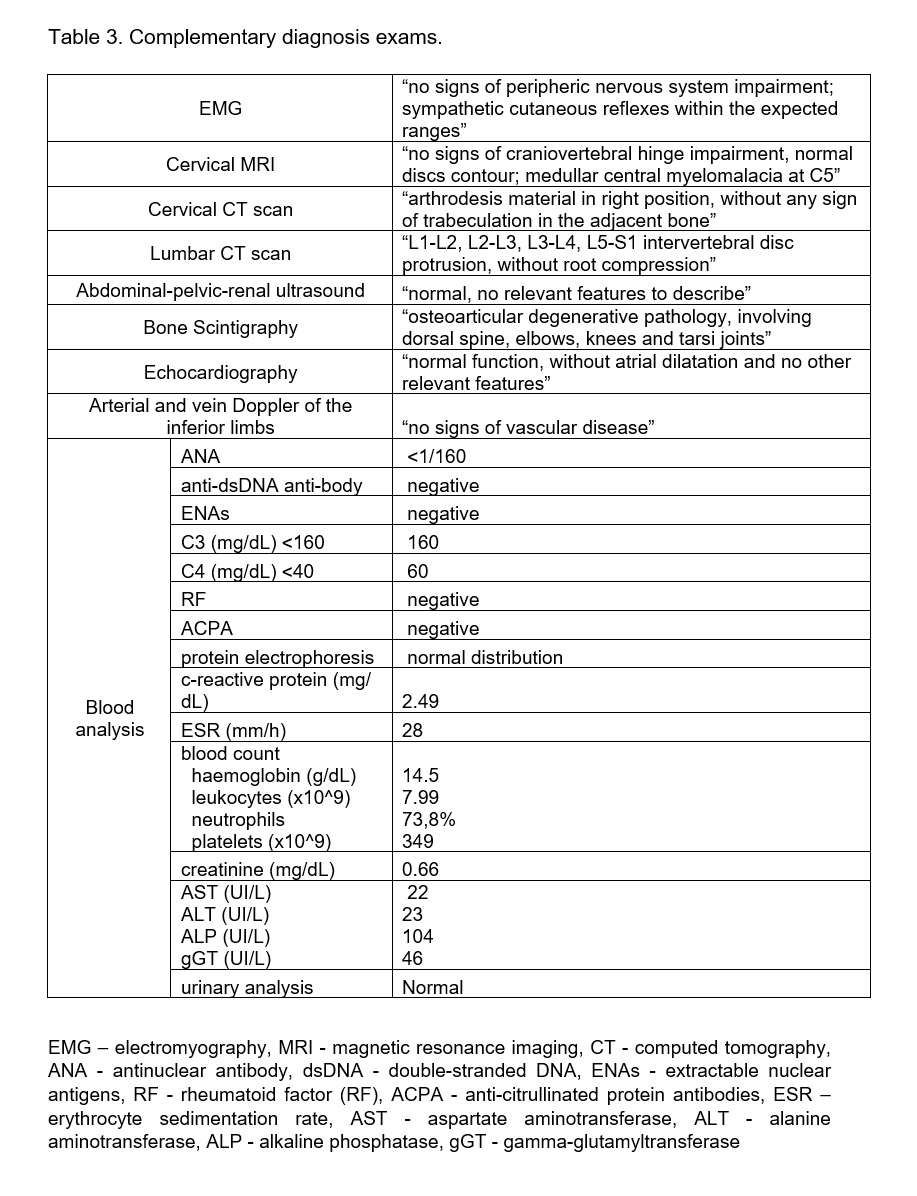

Despite several exams the patient remained without a diagnosis. (Table 3)

Considering that the clinical presentation, the evolution and the complementary diagnostic exams were not supporting any specific diagnosis, our diagnostic hypothesis was complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) involving the four limbs.

The pain seemed disproportionate in time and degree to the usual course of any known lesion, was not specific of any nerve territory or dermatome and had abnormal sensory, motor, vasomotor and atrophic findings with distal predominance.1,7

As there is no gold-standard method for diagnosis, CRPS is a clinical diagnosis.4 Using the Budapest criteria, the patient met at least one symptom and one sign of the four categories required and, obviously, the continuing pain which was disproportionate to the inciting event. Regarding the sensory category, the patient reported hyperesthesia and allodynia as major symptom. In the clinic, excruciating pain was provoked with light touch, passive joint movement and pinprick. In the vasomotor category, the patient reported different temperatures between the extremities of limbs and the rest of the body, and objectively they were colder and flushed (Fig’s 1 and 2). In reference to the sudomotor/edema category, hands, feet and the inferior 1/3 of both legs were edematous (Fig’s 1 and 2). The patient also complained about sweating changes but it was not observed in consultation. Concerning the motor/trophic category, she presented weakness of the four limbs that hindered mobility and daily tasks like writing or even eating. The Budapest criteria also takes into account that no other diagnosis better explains these signs and symptoms.

The differential diagnosis of CRPS is made with: Skin, muscle, joint or bone infections, excluded by clinical history and absence of inflammatory parameters elevation on blood analyses; Compartment syndrome, not compatible with the history of this patient; Peripheral vascular disease or deep vein thrombosis, which are very rare to manifest simultaneously on the four limbs and were not supported by the Echo-Doppler of the inferior limbs; Peripheral neuropathy, discarded by normal EMG; Chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease, such as systemic erythematous lupus or rheumatoid arthritis, excluded by clinical history, absence of arthritis and blood analysis (negative anti-nuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, anti–citrullinated protein antibody and anti-dsDNA antibody, and normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate and c-reactive protein); Raynaud syndrome, rejected because the vascular manifestations were permanent and did not worsen with cold; Secondary erythromelalgia, discarded by the lack of changes with temperature fluctuations.7,9

Even though CRPS diagnosis is clinical, recently bone scintigraphy was pointed as a sensitive technique to support this diagnosis when preformed within the first five months, showing increased radiotracer uptake near the region of interest. Unfortunately, symptoms were present for two years.4

Assuming this diagnosis in agreement with a multidisciplinary pain unit, we referred the patient to a pain consultation with previous experience with CRPS, for symptom management. Although, therapeutic approaches have been increasing in the past few years’ evidence is still controversial. The treatment of CRPS is composed by three main frames: physical and occupational therapy, psychological therapy, and pharmacological (non-steroid anti-inflammatories, corticosteroids, bisphosphonates, neuropathic pain medication, ketamine infusion, intravenous immunoglobulin, epidural clonidine, compound analgesic cream, opioids, anticonvulsants and antidepressants) and surgical interventions to manage pain.7 Surgical interventions, namely spinal cord stimulation, were considered due to the severity of the case, prolonged evolution and lack of control of the pain with multiple drugs and intolerance to several others that lead to low treatment compliance. The patient was also, referenced to a psychiatric consultation and physical therapy.8 At pain unit she was medicated with multiple pain control drugs, gradually, until reaching reasonable pain control that allowed her to cooperate with physical rehabilitation sessions – Codeine/paracetamol 30/500mg three times daily, Phenytoin 100mg two times daily, Pregabalin 300mg twice daily, Metamizol 575mg daily, Clonazepam 0,5mg daily, Venlafaxine 150mg daily, cyclobenzaprine 10mg daily, Acemetacin 90mg twice daily and Trazodone 150mg daily. Fortunately, the patient is making favorable progresses with the multidisciplinary approach and surgical intervention was postponed.

CONCLUSION:

This is a case of important relevancy, because CRPS is a rare disease, not commonly seen in an internal medicine clinic. Furthermore, the atypical presentation, affecting four limbs, and the unusual trigger, with symptoms arising immediately and after spine surgery, are not commonly described in this syndrome and, in our opinion, were contributors to the delayed diagnosis. This case highlights the need for an internal medicine approach in patients with systemic symptoms and a prolonged disease history. In addition, it is also an example of an advanced disease due to lack of diagnosis and appropriate treatment, with a very significant impact in the patient’s quality of life. Ergo, this case report underlines the importance of the clinical history and physical exploration, as, due to lack of gold standard tests and unclear disease etiology, these are sometimes the only tool that a doctor can rely on to diagnose and treat patients properly.

Figura I

Table 1. Budapest Clinical Diagnostic Criteria

Figura II

Table 2. List of prescribed medication over de past two years.

Figura III

Table 3. Complementary diagnosis exams

Figura IV

Figure 1. Both feet and lower legs presenting redness of the skin and edema

Figura V

Figure 2. Both hands with redness of the skin and edema

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1.Harden RN, Bruehl S, Stanton-Hicks M, Wilson PR. Proposed new diagnostic criteria for complex regional pain syndrome. Pain Med 2007; 8:326-231.

2.Ott S, Maihofner C. Signs and Symptoms in 1043 patients with complex regional pain syndrome. J Pain 2018; 19:599-611.

3.Ratti C, Nordio A, Resmini G, Murena L. Post-traumatic complex regional pain syndrome: clinical features and epidemiology. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2015;12(Suppl 1):11-6.

4.Birklein F, O’Neill D, Schlereth T. Complex regional pain syndrome: An optimistic perspective. Neurology 2015; 84:89-96.

5.Maleki J, LeBel AA, Bennett GJ, Schwartzman RJ. Patterns of spread in complex regional pain syndrome, type I (reflex sympathetic dystrophy). Pain 2000; 88:259-66.

6.Staton-Hicks M, Janig W, Hassenbusch S, et al. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy: changing concepts and taxonomy. Pain 1995; 63:127-33.

7.Eldufani J, Elahmer N, Blaise G. A medical mystery of complex regional pain syndrome. Heliyon 6 2020; e03329.

8.Harden RN, Oaklander AL, Burton AW, Perez RSGM, Richardson K, Swan M et al. Complex regional pain syndrome: practical diagnostic and treatment guidelines, 4th edition. Pain Med 2013; 14:180-229.

9.Turner-Stokes L, Goebel A. Guideline Development Group. Complex regional pain syndrome in adults: concise guidance. Clin Med (Lond) 2011; 11:596-600.