Case report

A 57-year-old-man with a relevant medical history of smoking (smoking load of 45 pack-year) and left nephrectomy after kidney neoplasia seven years ago (stable by now) was admitted to the emergency department with a 4-day history of pleuritic chest pain that improved with anti-inflammatory medication. There had been an episode of a flu-like syndrome in the previous month with spontaneous resolution. He reported no fever, chills, weight loss, or night sweats. Also, there was no history of animal contact, recent travels, new medication, or exposure to dusty environmental conditions.

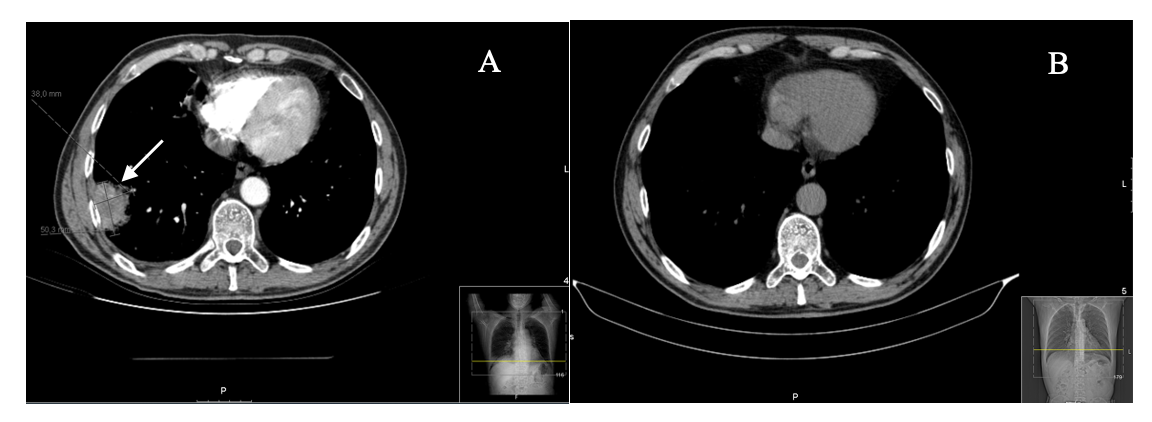

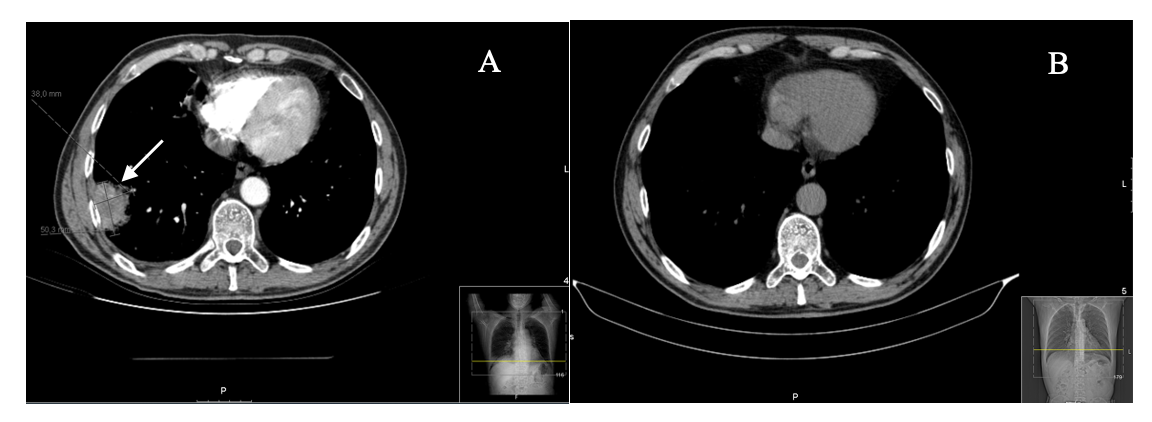

At the admission, he was hemodynamically stable, apyretic, with no alterations at auscultation, peripheral oxygen saturation (room air) of 92%, and no adenopathies were found. Laboratory testing showed leucocytosis (14.99x10^3/𝜇l; normal range 4,00-11,00 x 103/𝜇L) and increased C-reactive protein (50 mg/L; normal range 0-5 mg/L). The chest radiography presented a nodular infiltration in the right lower lobe subsequently clarified by CT scan showing a pulmonary mass in the periphery of the laterobasal segment of the right lower lobe measuring 50x38mm of largest transverse axes.

During hospitalization, he developed a cough with hemoptoic sputum and persisted with pleuritic chest pain. Autoimmune tests, including anti-neutrophil antibody (ANA), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), and rheumatoid factor (RF) were negative. Arterial blood gases, hepatorenal function, and electrolytes were in a normal range. There was no evidence of infection. An abdominal and pelvic tomography was performed showing a hepatic hemangioma with no other masses or lymphadenopathies. The bone scintigraphy showed findings compatible with degenerative bone disease. Since the pulmonary mass was peripheral, a transthoracic lung biopsy was performed.

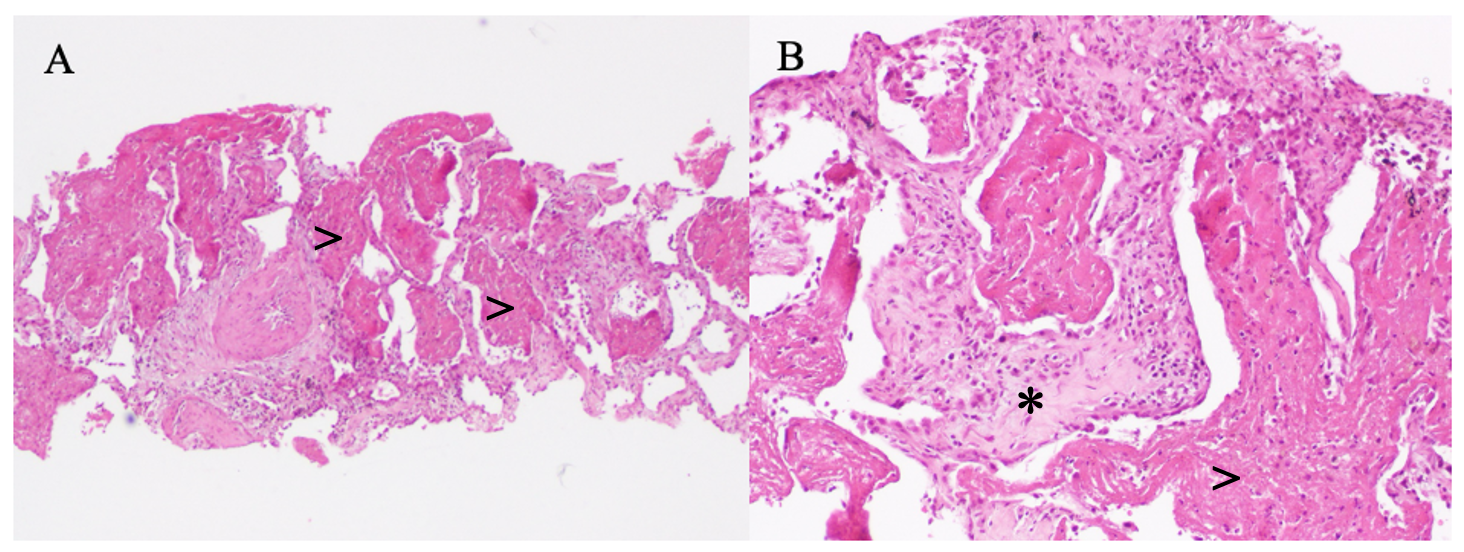

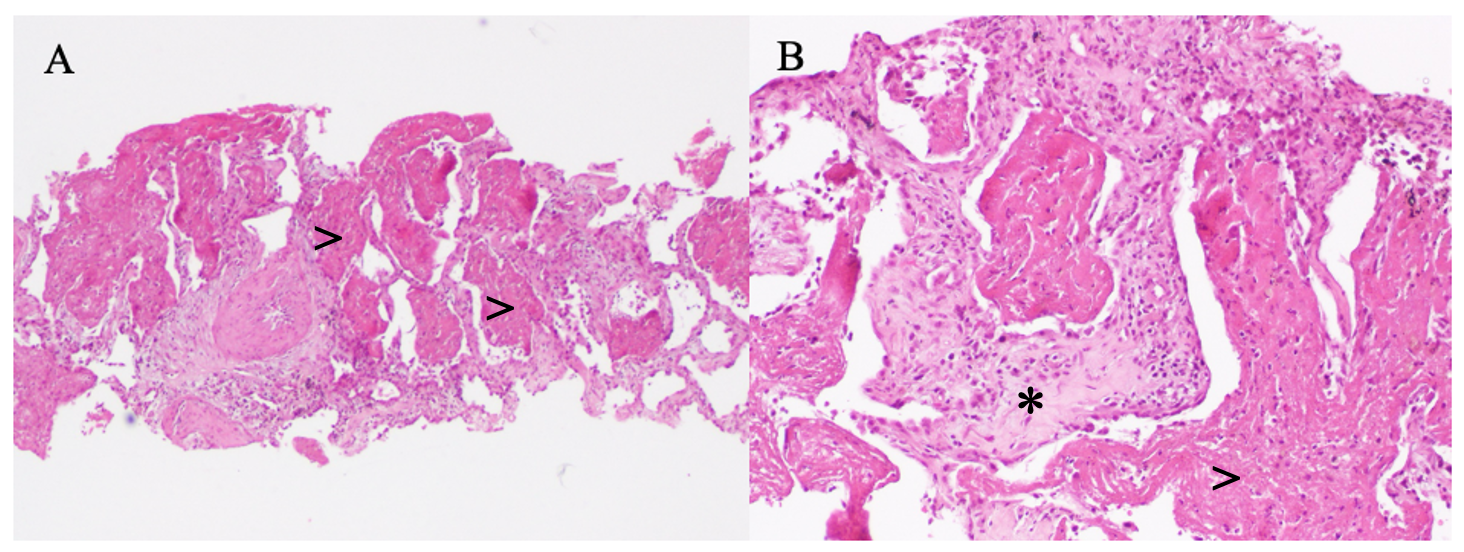

Histopathologic examination of the pulmonary parenchyma revealed mild or moderate septal enlargement by edema, accompanied by lymphocyte infiltration and neutrophil polymorphonuclear cells, and alveolar spaces filled with fibrinoid material (fibrin balls) with some neutrophils (Fig. 1). These findings were compatible with acute fibrinous organizing pneumonia.

A revaluation chest tomography was performed one month after discharge, and there was a significant reduction of the mass, measuring 30x17mm. After four months, the lesion completely disappeared, persisting only small residual atelectasis (Fig. 2). The patient had a total follow-up of 15 months, with no recurrence of symptoms or imaging findings.

No targeted therapy was administered during hospitalization or after discharge since the patient evolved with spontaneous remission.

Discussion

Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia is a rare illness, associated with acute or subacute lung injury, with a heterogenic presentation. It affects mainly males and may appear in all age groups with an average age of 62 years.1-3

It was first described in 2002 by Beasley, and in 2013 it appeared in the classification update of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia by the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society.4 This update in the classification of interstitial lung diseases allowed a more precise definition of some disease processes, determinate the prognosis and response to treatment. The approach of this group of diseases has become multidisciplinary and dependent upon the skills of pathologists, radiologists, and clinicians. Most important, the redefinition and standardization of terminology of distinct patterns, the recognition of new patterns and the heterogeneous course of some diseases, permitted to recruit patients into multicentre treatment studies and provide future investigation areas.

The most common symptoms of AFOP are cough, dyspnea, and fever, while chest pain, hemoptysis, and constitutional symptoms are less frequent.1-3 In our case, the symptomatology was very subtle and consisted mainly of chest pain and limited cough with hemoptoic expectoration during hospitalization.

Clinical presentation and disease progression can be acute or subacute. Severe symptoms and acute presentation can lead to rapid deterioration, sometimes leading to ventilatory failure, mechanical ventilation, and possibly a fatal progression. Subacute presentation, however, has a better response to treatment and slower progression and may even have a spontaneous recovery.1,5,6 Based on the clinical course of our patient, we can conclude that he had a subacute variety of the disease with spontaneous recovery.

Imaging chest findings also can vary and it is possible to find bilateral basilar infiltrates, diffuse infiltrates, nodular consolidations, ground-glass opacities, or nodular shadows.1,2,7,8 Sometimes it is difficult to make a differential diagnosis with pneumonia due to the presence of opacities and consolidation areas. In our case, the patient presented a nodular infiltration with no consolidation, patchy infiltrates, or “ground-glass” appearance and, since he had no evidence of infection, antibiotic treatment was withheld.

The manifestations described lack specificity, therefore a biopsy is essential to the diagnosis. AFOP is reported to have a histologic pattern with extensive airspace fibrin exudates that form “fibrin balls”. It differs from diffuse alveolar damage by not presenting hyaline membranes, from eosinophilic pneumonia by not presenting eosinophils, and from organizing pneumonia by not presenting organizing fibrosis.1,9,10 It is important to note that sampling limitation may lead to misdiagnosis because small biopsy tissues might not represent the intrinsic lesions. There are cases reported in the literature of lesions with a typical histological presentation of AFOP, but in which the final diagnosis was tuberculosis or tumor.11

The etiology can be idiopathic with no identified cause or associated with other conditions. It has been reported to be associated with lung infections (usually viral), hypersensitivity pneumonia, 4,12 connective tissue disease,4,13 adverse drug reactions,4,14 environmental or occupational exposure,15 lymphoma, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and lung transplantation. In our case, the patient had a viral infection in the previous month, although he had already fully recovered by the time he was admitted to the emergency department.

AFOP has no specific treatment guidelines described until this date. The most common treatment mentioned in case reports is corticosteroids and it seems to be effective in patients with a subacute presentation. Other medications have been used to treat AFOP such as antibiotics, cyclophosphamide, or azathioprine.1,7-10 Also, it is crucial to avoid occupational and environmental exposures and stop the use of drugs associated with this disease.

Since there is no ideal treatment for AFOP, the treatment of choice and therapy duration should be decided based on the medical course and etiology.

There are few cases of spontaneous remission described, but usually, treatment with antibiotics, corticosteroids, or both are initiated early in the disease course due to the nonspecific symptoms and imaging findings.

In conclusion, acute and fibrinous organizing pneumonia is a rare lung disease, with a histologic pattern of intra-alveolar fibrin, characterized by bilateral basilar infiltrates or nodular consolidations. It is essential to consider this entity in patients diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia when there is no response to antibiotic therapy or if the patient has a history of exposure to offending agents. Lung biopsy remains the gold standard since symptoms and CT images are not pathognomonic. In patients with a subacute presentation and slower progression, a wait-and-see attitude seems to be safe, although glucocorticoid treatment should be considered.

Figura I

Fig. 1: A: The alveolar spaces are dilated and filled with fibrinoid material that forms the so called “fibrin balls” (>). Haematoxylin and eosin stain (40x). B: Higher magnification shows alveolar septal expansion (*) accompanied by interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate. Note the alveolar spaces containing fibrin deposition (>) with some neutrophils. Haematoxylin and eosin stain (100x).

Figura II

Fig.2: A: CT at admission showing a pulmonary mass measuring 50x38mm. B: CT of revaluation after 4 months with no evidence of the lesion.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

References:

1) Beasley MB, Franks TJ, Galvin JR, Gochuico B, Travis WD. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia: a histological pattern of lung injury and possible variant of diffuse alveolar damage. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2002;126:1064–070.

DOI: 10.1043/0003-9985(2002)126<1064:AFAOP>2.0.CO;2

2) Wang K, Du X, Wu Q, Cheng D. A case report of acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia. Medicine,2019;98(49):e18140

DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018140

3) Arnaud D, Surani Z, Vakil A, Varon J, Surani S. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia: A case report and review of the literature. Am J Case Rep. 2017; 18: 1242–1246. DOI: 10.12659/ajcr.905627

4) Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, King TE Jr, Lynch DA, Nicholson AG,et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement: Update of the International Multidisciplinary Classification of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2013; 188(6):733-48

DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST

5) López-Cuenca S, Morales-García S, Martín-Hita A, Frutos-Vivar F, Fernández-Segoviano P, Esteban A. Severe acute respiratory failure secondary to acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation: a case report and literature review. Respir Care.2012;57(8):1337-41. DOI: 10.4187/respcare.01452

6) Nguyen LP, Ahdoot S, Sriratanaviriyakul N, Zhang Y, Stollenwerk N, Schivo M, et al. Acute Fibrinous and Organizing Pneumonia Associated With Allogenic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Successfully Treated With Corticosteroids. A Two-Patient Case Series. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2016; 4 (2): 1-6.

DOI: 10.1177/2324709616643990

7) Gomes R, Padrão E, Dabó H, Soares Pires F, Mota P, Melo N, et al. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia. A report of 13 cases in a tertiary university hospital. Medicine. 2016;95(27): e4073

DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004073

8) Lu J, Yin Q, Zha Y, Deng S, Huang J, Guo Z, et al. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia: two case reports and literature review. BMC Pulm Med.2019;19:141. DOI: 10.1186/s12890-019-0861-3

9) Hashisako M, Fukuoka J. Pathology of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med. 2015. 9 (Suppl 1): 123-33. DOI: 10.4137/CCRPM.S23320

10) Paraskeva M, McLean C, Ellis S, Bailey M, Williams T, Levvey B, et al. Acute Fibrinoid organizing pneumonia after lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2013, 187(12):1360-8

DOI:10.1164/rccm.201210-1831OC

11) Feng AN, Cai HR, Zhou Q, Zhang YF, Meng FQ. Diagnostic problems related to acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia: misdiagnosis in 2 cases of lung consolidation and occupying lesions. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7(7):4493-7. PMID: 25120840

12) Hariri LP, Mino-Kenudson M, Shea B, Digumarthy S, Onozato M, Yagi Y, et al. Distinct histopathology of acute onset or abrupt exacerbation of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Hum Pathol.2012; 43(5):660-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.06.001

13) Balduin R, Giacometti C, Saccarola L, Marulli G, Rea F, Bartoli M, et al. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia in a patient with collagen vascular disease “stigma”. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis.2007;24(1):78-80. PMID: 18069424

14) Yokogawa N, Alcid DV. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia as a rare presentation of abacavir hypersensitivity reaction. AIDS.2007;21(15):2116-7.

DOI: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f08c5a

15) Guimarães C, Sanches I, Ferreira C. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia. BMJ Case Rep.2012, 2012.

DOI: 10.1136/bcr.01.2011.3689