BACKGROUND

MDS is a stem cell disorder characterized by dysplastic and ineffective haematopoiesis, and is a variable risk to progression to acute leukaemia (AL).1 Those patients may have defects in one or more cell lineages.1,2 It is a common hematologic disorder, although the precise incidence of secondary MDS is not known.3 Usually it occurs most commonly in older adults, with a median age at diagnosis above 65 years, with a male predominance.3 The clinical manifestations of MDS are nonspecific, sometimes the patients are asymptomatic and blood count abnormalities is what draws clinicians attention.4 Because anemia is usually the most common cytopenia, manifestations associated are usually the most prevalent, which includes fatigue that can sometimes be out of proportion to the degree of anemia.4 The association between MDS and autoimmunity has already been well described,1,2 including manifestations such as pulmonary nodulations, although not the most common.5,6

The diagnosis of OP associated with MDS requires a high level of suspicion, because it does not differentiate from other forms of OP.7-9 OP is a distinct histopathologic lesion defined by a histologic pattern and the corresponding clinical-radiologic-pathologic diagnosis.8 The histologic pattern is defined by a nonspecific inflammation with the presence of buds of granulation tissue present in the lumen of the distal airspaces.7,8 OP is a dynamic process that integrates nonspecific clinical manifestations, the imaging features (alveolar opacities visualized in the chest-x rays, that are low density, migratory and recurrent), and the decision of lung biopsy to obtain a definite diagnosis.8,9

It is important to distinguish OP from other causes of pulmonary infiltrates in patients with hematologic malignancies because this pulmonary reaction appears to respond to corticosteroid therapy.9,10

CASE PRESENTATION

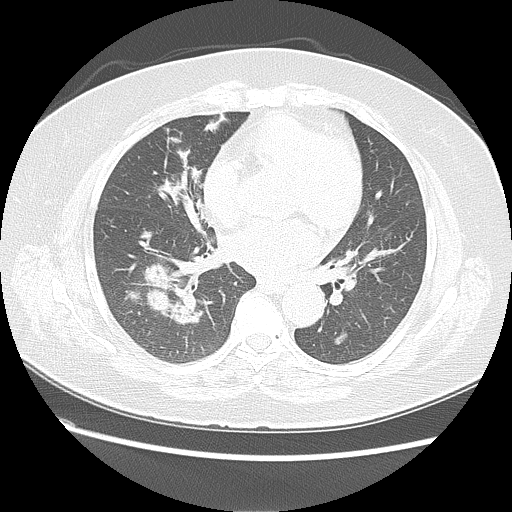

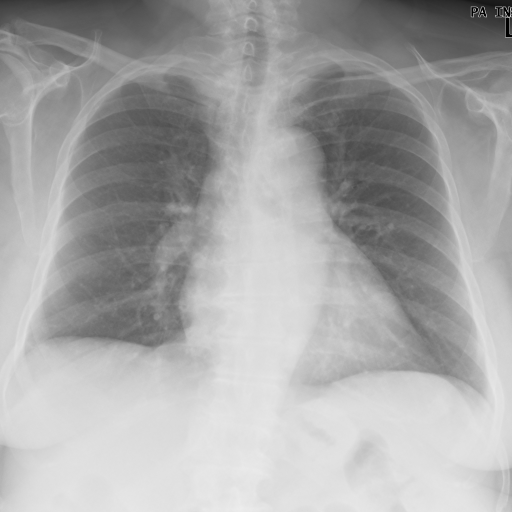

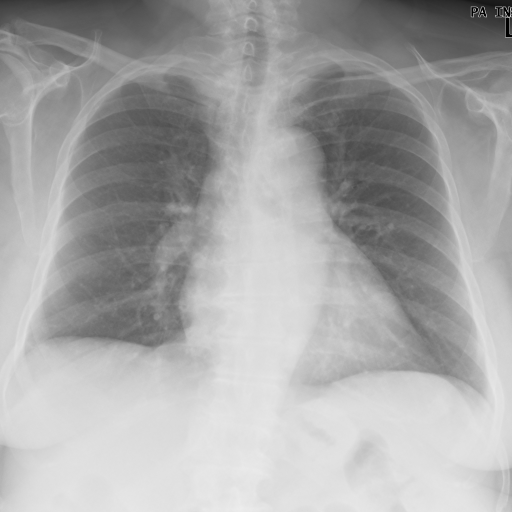

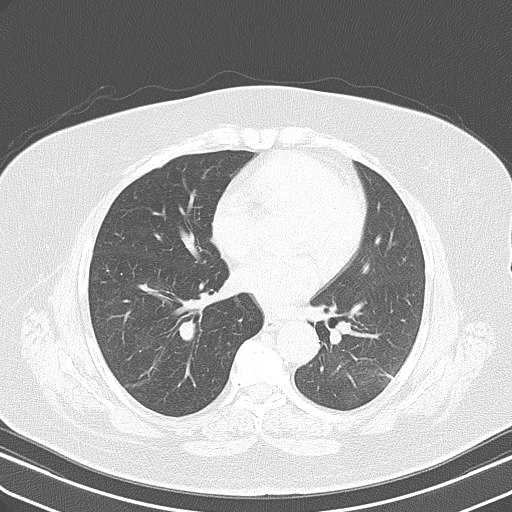

A 70-year-old woman, with history of hypertension, dyslipidaemia and orthopaedic surgery, presented in the emergency room with fever (maximum 38ºC) and anorexia for the past 3 days, unquantified weight loss and night sweats. Physical examination was without major changes. She had already been medicated with antibiotic at the beginning of the symptoms, with no improvement. Complete blood count revealed a normocytic anemia (Hb 8.4 g/dL with MCV of 96.4 fL), leukopenia (1.7x10^9/L) and a mild thrombocytopenia (150x10^9/L). Peripheral blood smear showed 2% of cells with morphological characteristics of immaturity. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, were increased, 45 mm/h and 26.66 mg/dL, respectively. Chest x-ray showed pulmonary nodules (Fig. 1). At chest computed tomography, the pulmonary parenchyma showed multiple confluent peribroncovascular nodular opacities, with para-hilar distribution dispersed throughout pulmonary lobes (Fig. 2). Based on work up findings, pneumonia diagnosis was admitted, and antibiotics were started.

She was admitted to the Internal Medicine ward to further workup. In the first days of hospital stay the patient maintained fever that didn`t give in to antipyretic. All cultures were negative (blood, sputum and urine) and she tested negative to HIV 1 and 2, Legionella, Coxiella, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, parvovirus and interferon-gamma release assay. The folic acid value was in normal range, but vitamin B12 (2xUNL) and ferritin (12xUNL) were above normal range. The electrophoretic proteinogram didn’t show relevant alterations as well as immunoglobulins count. Despite undergoing several cycles of antibiotics with piperacillin/tazobactam (7 days), azithromycin (5 days), vancomycin (5 days) and ertapenem (5 days), there was a progressive clinical, analytical, and radiologic worsening. A bronchoscopy was performed and the bronchoalveolar aspirate cytology showed reactive cells with a predominance of polymorphonuclear cells, and the wash cytology was also consistent with the presence of inflammatory cells. No biopsy was performed due to blood dyscrasia and high risk of bleeding associated to SMD and clinical frailty. After improvement of bleeding risk she performed a bone marrow aspirate that revealed the presence of 10.7% of blasts and maturations defects suggestive of MDS with increased type II blasts. There were no phenotype alterations or alterations on FISH technique. The bone marrow biopsy showed infiltration with big cells with blastic nucleus and coarse chromatin, with a left shift in the granulocytic series and diffusely increase in the reticulin (grade 2); it also showed in the immunocytochemical study an increase in the number of blasts, marked with CD34 and CD117, predominantly dispersed, approaching 5-6% of cellularity. These findings were suggestive of MDS with excess blasts.

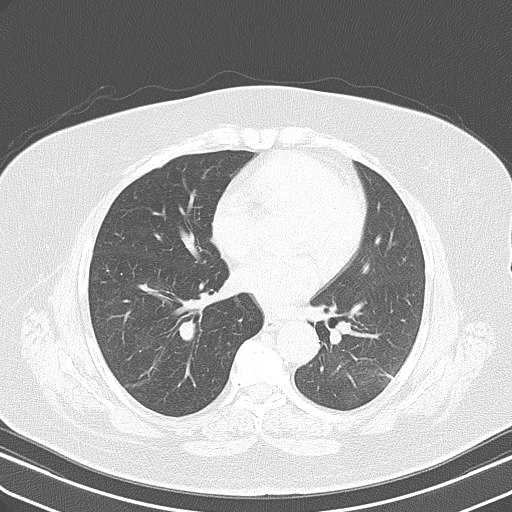

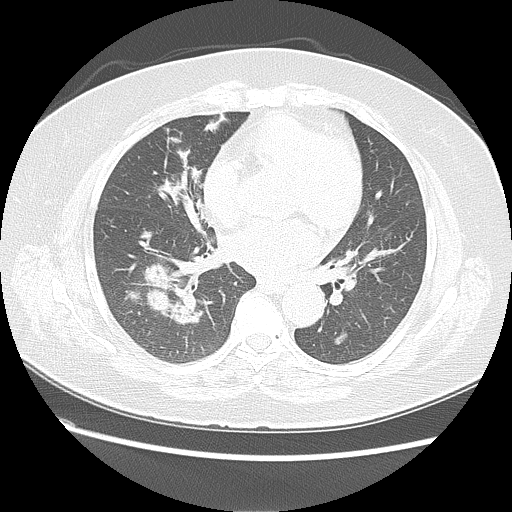

After excluded infectious diagnosis, it was decided to start empirically corticosteroid therapy with prednisolone 0.75mg/Kg/per day. After several days, a new chest x-ray (Fig. 3) and thoracoabdominopelvic computed tomography (Fig. 4) were made and showed an important reduction in number and extension of the densified parenchymal areas when compared to the admission exam, probably of inflammatory nature, suggesting organizing pneumonia. Clinically she showed clear improvement, with sustained apyrexia was well as improvement in inflammatory parameters and pancytopenia.

OP was then admitted in the context of MDS. She was referred to Hematology and Internal Medicine consultation for treatment and follow-up.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient is currently followed in Hematology and Internal Medicine consultation. The initial approach to MDS was through a watch and wait strategy with transfusion of red blood cells or platelets when needed. In the present time, she is being treated with azacytidine after transformation for oligoblastic acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), with occasional transfusion need.

The reduction of corticosteroid therapy was accompanied by clinical evaluation and chest X-ray every 3 months to evaluate possible relapse of OP. The patient is currently medicated with 15 mg of prednisolone daily with no alterations in the last chest x-ray she performed.

Despite transformation of the MDS to AML, the patient maintained a good performance status (ECOG 2).

DISCUSSION

OP is a histopathologic pattern that can represent a non-specific reparative process associated with other primary pathologic condition such as infection, infarction, carcinoma, and Wegener´s granulomatosis.5,9In other patients OP may be the primary pathologic process and occurs without a recognizable cause or associated disease.4,9OP has also been reported in patients with hematologic malignancies, and potential etiologies include infection, radiation and chemotherapy.5,9OP associated with hematologic disorders has also been reported in patients with acute leukemia, Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and MDS, however,the frequency is quite rare.7

Pulmonary complications in hematological malignancies are often caused by infection, but sometimes associated with an underlying disease such as OP.7MDS itself has been implicated as a potential risk factor for OP.1,2Daniels et al, presented a retrospective study of OP cases related to hematologic malignancies, in which only one case of OP was related to MDS.9

Patients with pulmonary infiltrates, in hematologic malignancy, are common and result from infection, pulmonary edema, hemorrhage, and malignancy.9OP unrelated to infection or any other recognizable cause, has been described in patients with hematologic malignancies.9Despite the low incidence, OP should be considered in all patients with hematologic malignancies who present themselves with new onset respiratory symptoms or lung alteration findings in radiography or computed tomography.6,9 It is also required a tissue biopsy for definitive diagnosis of OP.8,9

In most published case reports the infective possible causes for the pulmonary manifestations were ruled out.1,7–10 The necessity of ruling out a possible infection is mandatory before the administration of corticosteroids.10 OP is highly sensitive to corticosteroids and studies support a favorable prognosis and beneficial effect of the therapy when a diagnosis of OP is found in association with hematologic malignancy.9,10

In our case we recognized respiratory clinic, and radiological findings at chest-ray and CT that could be associated with hematological abnormalities. We noticed worsening of the blood count along with fever and respiratory symptoms. Patient performed broad-spectrum antibiotics without any improvement. Although desirable, no biopsy was performed due to blood dyscrasia and high risk of bleeding associated to SMD and clinical frailty. Considered a lifesaving situation, the diagnosis was assumed after therapeutic test: no response to broad-spectrum antibiotics and improvement of the pulmonary lesions and fever, after corticosteroids therapy.

Histologic confirmation with a biopsy, is always desirable to achieve a definite diagnosis. Nevertheless, the diagnosis of OP is possible, in presence of a typical clinic-radiologic presentation if biopsy it is not possible, as it was in case of our patient.8

There is no relation between this specific presentation and the overall outcome of the patient.9 The overall mortality is high and dead is rarely attributed to respiratory findings, but rather from progression of MDS.9 The OP as prognostic variable is not well studied and results are contradictory.5,7

In conclusion, we report a rare case of MDS presenting with OP, assumed after full response of pulmonary lesions to corticosteroid therapy in a dose of 0.75 mg/Kg/day and treatment should be kept for at least 6 to 12 months.8

Figura I

Chest x-ray before treatment with corticosteroid

Figura II

Chest computed tomography before treatment with corticosteroid

Figura III

Chest x-ray after treatment with corticosteroid

Figura IV

Chest computed tomography after treatment with corticosteroid

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Merrill A, Smith H. Myelodysplastic Syndrome and Autoimmunity: A Case Report of an Unusual Presentation of Myelodysplastic Syndrome. Case Rep Hematol. 2011;2011:1-4. doi: 10.1155/2011/560106.

2. Seguier J, Gelsi-Boyer V, Ebbo M, et al. Autoimmune diseases in myelodysplastic syndrome favors patients survival: A case control study and literature review. Autoimmun Rev. 2019;18(1):36-42. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2018.07.009.

3. Smith A, Howell D, Patmore R, Jack A, Roman E. Incidence of haematological malignancy by sub-type: a report from the Haematological Malignancy Research Network Clinical Studies. Br J Cancer. 2011:1684-92. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.450.

4. Aster JC, Stone RM. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of the myelodysplastic syndromes. UpToDate. 2020. [Accessed March 2020]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-myelodysplastic-syndromes

5. Lamour C, Bergeron A. Non-infectious pulmonary complications of myelodysplastic syndromes and chronic myeloproliferative disorders. Rev Mal Respir. 2011;28(6):e18-e27. doi: 10.1016/j.rmr.2009.04.001.

6. Calvillo Batllés P, Carreres Polo J, Sanz Caballer J, Salavert Lletí M, Compte Torrero L. Hematologic neoplasms: Interpreting lung findings in chest computed tomography. Radiol (English Ed). 2015;57(6):455-70. doi: 10.1016/j.rxeng.2015.09.001

7. Asano T, Fujii N, Niiya D, et al. Complete resolution of steroid-resistant organizing pneumonia associated with myelodysplastic syndrome following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Springerplus. 2014;3(1):1-6. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-3

8. Cordier JF. Cryptogenic Organizing pneumonia. Clin Chest Med. 2004;25:727-38. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2004.06.003

9. Daniels CE, Myers JL, Utz JP, Markovic SN, Ryu JH. Organizing pneumonia in patients with hematologic malignancies: A steroid-responsive lesion. Respir Med. 2007;101(1):162-8. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.03.035

10. Yamamoto M, Murata K, Kiriu T, Kouzai Y, Takamori M. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia with myelodysplastic syndrome: Corticosteroid monotherapy led to successful ventilator weaning. Intern Med. 2016;55(21):3155-3159. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.55.6864