Introduction

GCA is an inflammatory disease of medium and large arteries. It typically presents in patients over 70 years of age with headache, scalp tenderness, jaw claudication and sudden visual loss. There are no specific laboratory tests for the diagnosis of GCA, but an elevated ESR as well as anemia are hallmarks of this disease, with a high sensitivity. Patients with GCA have a higher risk of strokes, although this is rare.

Case Report

A 78-year-old man, with history of arterial hypertension and smoking (120 pack years) presented to the emergency department with bitemporal and occipital headache and episodes of bilateral scotomas and transient bilateral visual loss with a duration of a few minutes for the past fifteen days. For the past 24 hours he also presented periods of confusion, right hemiparesis (muscle strength grade 3/5), right hemihypoesthesia, central right facial paralysis and paralysis of the left third cranial nerve. The patient had lost 11% of his body weight during the past month. He denied pain in his joints, mandibular claudication, fever, myalgias or symmetrical loss of strength in scapular or pelvic girdle.

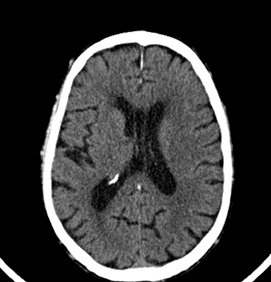

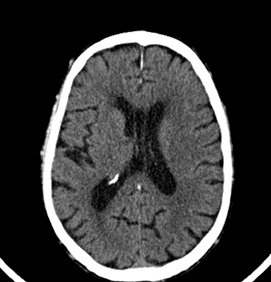

His initial laboratory workout was unremarkable, with a normal serum C-reactive protein (CRP) and ESR 29mm/hr (normal less than 22mm/hr). Head CT scan showed a discrete hypodensity near the left superiorcorona radiatawith no mass effect, probably with a vascular origin and impossible to datewith this imaging technique (Fig. 1). Doppler ultrasound of the temporal arteries showed permeability of all studied segments, highlighting the increase in flow velocity in the left middle cerebral artery, right vertebral artery and basilary artery and increased pulsatility indexes, reflecting arterial inelasticity. Permeability of both superficial temporal arteries, frontal and parietal branches, with extensive fibrous and hypoechoic reinforcement of the arterial wall along both arterial axes, protruding into the arterial lumen, causing an increase in flow velocity, suggestive of stenosis. These findings are suggestive of an inflammatory process in the arterial wall.

The patient was admitted to the internal medicine ward under the suspicion of GCA with Weber syndrome. In view of possible cerebrovascular vasculitic involvement, the patient was started on methylprednisolone 1g for three days, and after that oral prednisolone 1mg/kg/day. Brain MRI performed on the forth day after admission revealed new ischemic infarcts in the vertebrobasilar territory and left medium cerebral artery (Fig. 2).

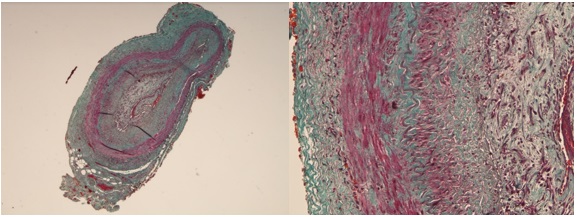

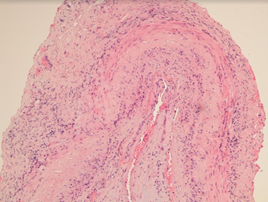

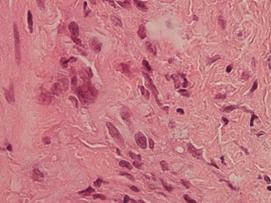

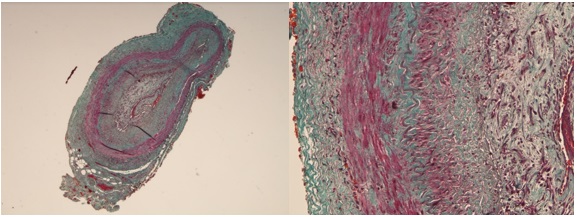

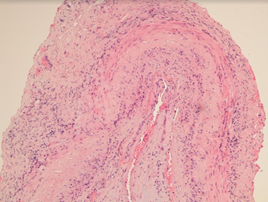

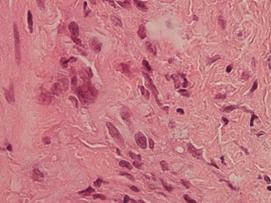

Bilateral temporal artery biopsies were done on the 7th day of hospitalization and were positive for GCA showing transmural inflammation and the presence of multi-nucleated giant cells in the arterial walls (Figures 3A and 3B, 4 and 5).

The patient gradually worsened his neurologic status, increasing the degree of paralysis, and developing ataxia and dysarthria. He was started on cyclophosphamide 750mg/m2on the 18thday after admission. The patient died of nosocomial pneumonia 41 days after hospital admission.

Discussion

GCA affects large and medium-sized vessels and is the most common systemic vasculitis.1 The incidence in southern Europe and Mediterranean countries is less than 10 per 100.000 in people over the age of 50. Its peak incidence is between ages of 70 and 79.2

Systemic symptoms are frequent and vascular involvement can be widespread. There are typical symptoms associated with GCA, usually related to the involvement of cranial branches of the aortic arch, such as headache, scalp tenderness, jaw claudication, and visual disturbances. One must be aware of the existence of atypical presentations since these can delay the diagnosis and treatment and therefore increase the risk of complications.

Stroke is uncommon in GCA. The occurrence of stroke in the first four weeks of the diagnosis of GCA is reported in 3% of the patients.3A recent French multicentric retrospective analysis4showed that patients with stroke were older and more frequently males. The frequency of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy was higher in patients with stroke and overall survival was decreased in GCA patients with stroke comparatively to patients without stroke. The most common territory for these events is the vertebrobasilar arteries, resulting in vertigo, ataxia, dysarthria, homonymous hemianopsia or bilateral cortical blindness. Bilateral vertebral artery involvement can cause rapidly progressive brainstem and/or cerebellar neurologic deficits with high mortality.

Weber syndrome, is a form of stroke characterized by the presence of an ipsilateral oculomotor nerve palsy and contralateral hemiparesis or hemiplegia. It is caused by midbrain infarction as a result of occlusion of the paramedian branches of the posterior cerebral artery or of basilar bifurcation perforating arteries.5

The original diagnostic recommendations advised temporal artery biopsy in every case of suspected GCA.6Since then, a large amount of good-quality data demonstrated that imaging (temporal arteries ultrasound or MRI of cranial arteries when ultrasound is inconclusive or unavailable) and biopsy have similar diagnostic value if assessors are proficient in these techniques.7This case reports to the year of 2016, when temporal artery biopsy was the gold-standard.

There is no specific blood biomarker for GCA. Normochromic anemia is often present; many patients also have a reactive thrombocytosis and the leukocyte count is usually normal or only slightly elevated. Most patients have elevated acute phase reactants at disease onset.8An elevated ESR (>50mm/h) is a hallmark of this disease and one of the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for GCA.9Laboratory testing will generally reveal elevated ESR and CRP (the sensitivity of an elevated ESR is 84% and CRP is 87% and both have a specificity of 30%).8In our case, the patient presented only mildly increased ESR, which is rare in patients with GCA (5-30%).10To our information no studies have been done on the values of ESR in patients with intracranial involvement.

Corticotherapy should be started whenever there is a suspicion of GCA and should not be postponed until after the biopsies since for the first 14 days of corticotherapy the signs of vasculitis remain present in the specimen.9If there are no symptoms of ischemia, therapy can be started with 40 to 60mg of prednisolone/day and the dose can be increased until symptomatic control is achieved.11Pulse therapy with intravenous methylprednisolone is not recommended in non-complicated disease. However if there is vision loss at diagnosis, diplopy or a cerebrovascular event, it is recommended to start with 1g/day for three days, followed by oral therapy.12If symptoms worsen, it is possible to increase the dose of corticosteroids or to start other therapies, such as cyclophosphamide. Cyclophosphamide is a safe therapeutic option for remission induction in GCA refractory to standard immunosuppressive treatment.13It can also be an option for patients with corticosteroid-dependent disease or with severe corticosteroid related side effects.14The most recent guidelines now propose the use of tocilizumab or methotrexate as adjunctive treatment for GCA in situations where glucocorticoid-related toxicities have ensued or are anticipated.6

Figura I

Head CT scan with discrete hypodensity near the left superior corona radiata.

Figura II

Brain MRI showing new ischemic infarcts in the vertebrobasilar territory and left medium cerebral artery.

Figura III

Images 3A and 3B – transverse sectioning of the temporal artery showing a fibromuscular thickening of the intima layer and reduction of the vascular lumen (Masson trichrome).

Figura IV

Mild to moderate inflammatory infiltrate in the three layers (mainly lymphocytes) (H&E stain).

Figura V

Multinucleated giant cell (H&E stain).

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Systemic vasculitis in adults in northwestern Spain, 1988-1997. Clinical and epidemiologic aspects. González-Gay MA, García-Porrúa C.Setembro de 1999, Medicine (Baltimore), Vol. 78, pp. 292-308.

2. Epidemiology of giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica. González-Gay MA, Vasquez-Rodriguez TR, Lopez Diaz MJ, Miranda Filloy JA, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Martin J, Llorca J. 2009, Arthritis Rheum., Vol. 61 (10), p. 1454.

3. Strokes at time of disease diagnosis in a series of 287 patients with biopsy-proven gian cell arteritis. Gonzalez-Gay MA, Vazquez-Rodriguez TR, Gomez-Acebo I, Pego-Reigosa R, Lopez-Diaz MJ, Vasquez Triñanes MC, Miranda-Filloy JA, Blanco R, Dierssn T, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Llorca J. Julho de 2009, Medicine (Baltimore), Vol. 88 (4), pp. 227-35.

4. Ischemic stroke in giant-cell arteritis: French retrospective study. Pariente A, Guédon A, Alamowitch S, Thietart S, Carrat F, Delorme S, Capron J, Cacciatore C, Soussan M, Dellal A, Fain O, Mekinian A. May de 2019, J Autoimmun, Vol. 99, pp. 48-51.

5. Midbrain Infarction Presenting with Weber’s Syndrome and Central Facial Palsy: A Case Report. Algin DI, Tafier F, Aydin S, Aksakalli E. 2009, Nöropsikiyatri Arşivi, Vol. 46 (4), pp. 197-9.

6. EULAR recommendations for the management of large vessel vasculitis. Mukhtyar C, Guillevin L, Cid MC, et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:318–23.

7. EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging in large vessel vasculitis in clinical practice. Dejaco C, Ramiro S, Duftner C, et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:636–43.

8. Utility of Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate and C-Reactive Protein for the Diagnosis of Giant Cell Arteritis. Kermani TA, Schmidt J, Crowson CS, Ytterberg SR, Hunder GG, Matteson EL, Warrington KJ. June de 2012, Semin Arthritis Rheum , Vol. 41(6), pp. 866–71.

9. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of giant cell arteritis. Hunder GG, Bloch DA, Michel BA, et al. 1990, Arthritis Rheum, Vol. 33, pp. 1122–8.

10. Giant cell arteritis with an erythrocyte sedimentation rate lower than 50. Martínez-Taboada VM, Blanco R, Armona J, Uriarte E, Figueroa M, Gonzalez-Gay MA, et al. 2000, Clin Rheumatol, Vol. 19, pp. 73–5.

11. Daily and alternate-day corticosteroid regimens in treatment of giant cell arteritis: comparison in a prospective study. Hunder GG, Sheps SG, Allen GL, Joyce JW. 1975, Ann Intern Med , Vol. 82, p. 613.

12. Treatment of giant cell arteritis using induction therapy with high-dose glucocorticoids: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized prospective clinical trial. Mazlumzadeh M, Hunder GG, Easley KA, Calamia KT, Matteson EL, Griffing WL, Younge BR, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. October de 2006 , Arthritis Rheum, Vol. 54(10), pp. 3310-8.

13. Treatment of refractory giant cell arteritis with cyclophosphamide: a retrospective analysis of 35 patients from three centres. Loock J, Henes J, Kotter I, et al. 2012, Clin Exp Rheumatol , Vol. 30 (Suppl 70), pp. 70-6.

14. Is there a place for cyclophosphamide in the treatment of giant-cell arteritis? A case series and systematic review. de Boysson H, Boutemy J, Creveuil C, Ollivier Y, Letellier P, Pagnoux C, Bienvenu B. August de 2013 , Semin Arthritis Rheum, Vol. 43(1), pp. 105-12.