INTRODUCTION

CS is a rare disease that results from prolonged exposure to excess glucocorticoids which clinical presentation is very variable. CS is traditionally classified as ACTH-dependent or ACTH-independent. ATCH-dependent CS represents 80-85% of the cases, of these, Cushing disease is the most frequent (68%), followed by ectopic ATCH production causes (12%) and < 1% due corticotropin-releasing hormone producing tumours.1,2 Ectopic ACTH secretion is generally associated to CPCP, pulmonary carcinoid tumour or less frequently, neuroendocrine tumours (NETs), thymic NETs, medullary thyroid tumours and pheochromocytoma.1,5

CASE PRESENTATION

An 86-year-old male, with a past medical history of tobacco consumption, colonic diverticulosis with two previous episodes of hospital admission with bleeding and symptomatic anaemia and a recent diagnosis of heart failure, medicated with ACEi, spironolactone and furosemide. He was admitted to our ward with a recent onset of nominal aphasia, depression, uncontrolled hypertension and glycaemia. On admission, physical examination revealed no other focal neurological deficit and showed signs of congestion, with pulmonary and peripheral oedema and mild hypoxemia (SpO2 89.5% with FiO2 21%). Blood work showed hypokalaemia (K+2.9 mEq/L, Mg2+1.84 mg/dL, Na+145 mEq/L, Cl-97 mEq/L) and metabolic alkalosis (pH 7.51; pCO2 48.6 mmHg; pO2 54 mmHg HCO3- 39 mmol/L). CT-angiography and head and neck doppler sonography showed no acute changes. With the initial supportive treatment with intravenous diuretic and potassium reposition, there was a transient clinical improvement of the neurological symptoms but progressive worsening of the oedema with persistent hypokalaemia, hypertension and hyperglycaemia. Further testing showed proteinuria in the nephrotic range, high levels of urinary potassium and high serum ACTH (328 pg/mL; reference: < 46 pg/mL) and cortisol (83.9 mg/dL; reference: < 50 mg/dL) as well as high 24h urinary excretion of cortisol (6812 mg/24 hours; reference: 4.3 – 176 mg/24 hours).

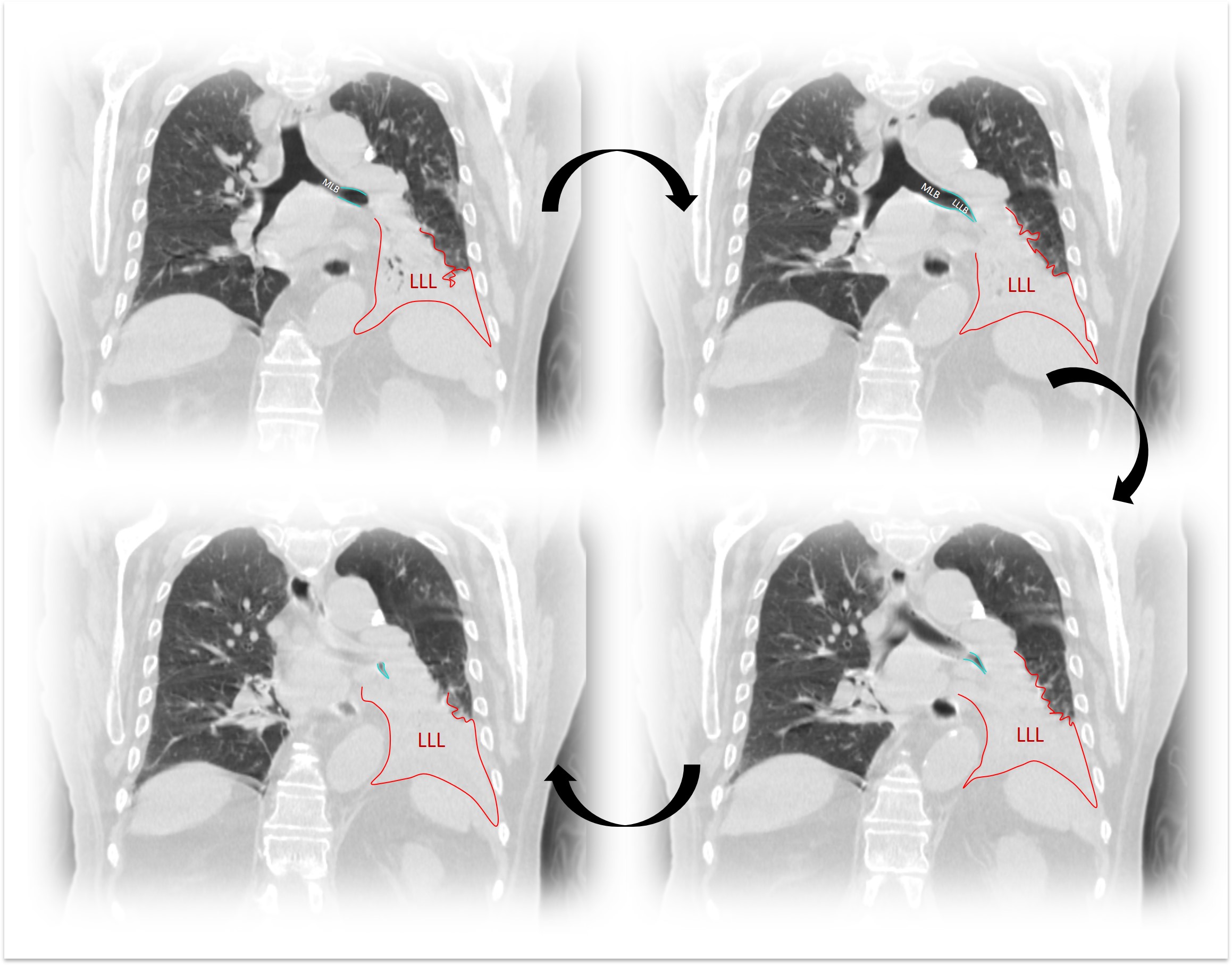

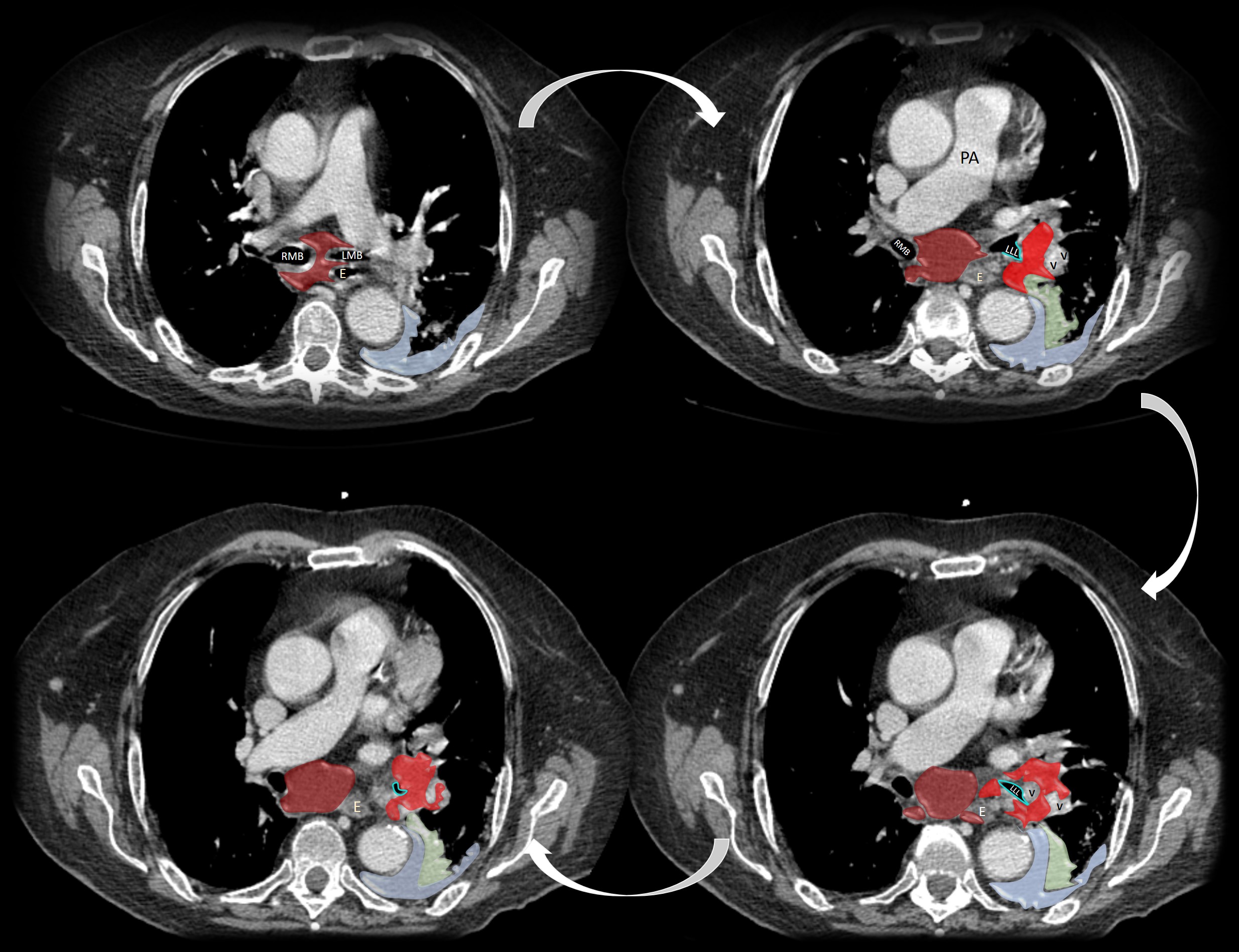

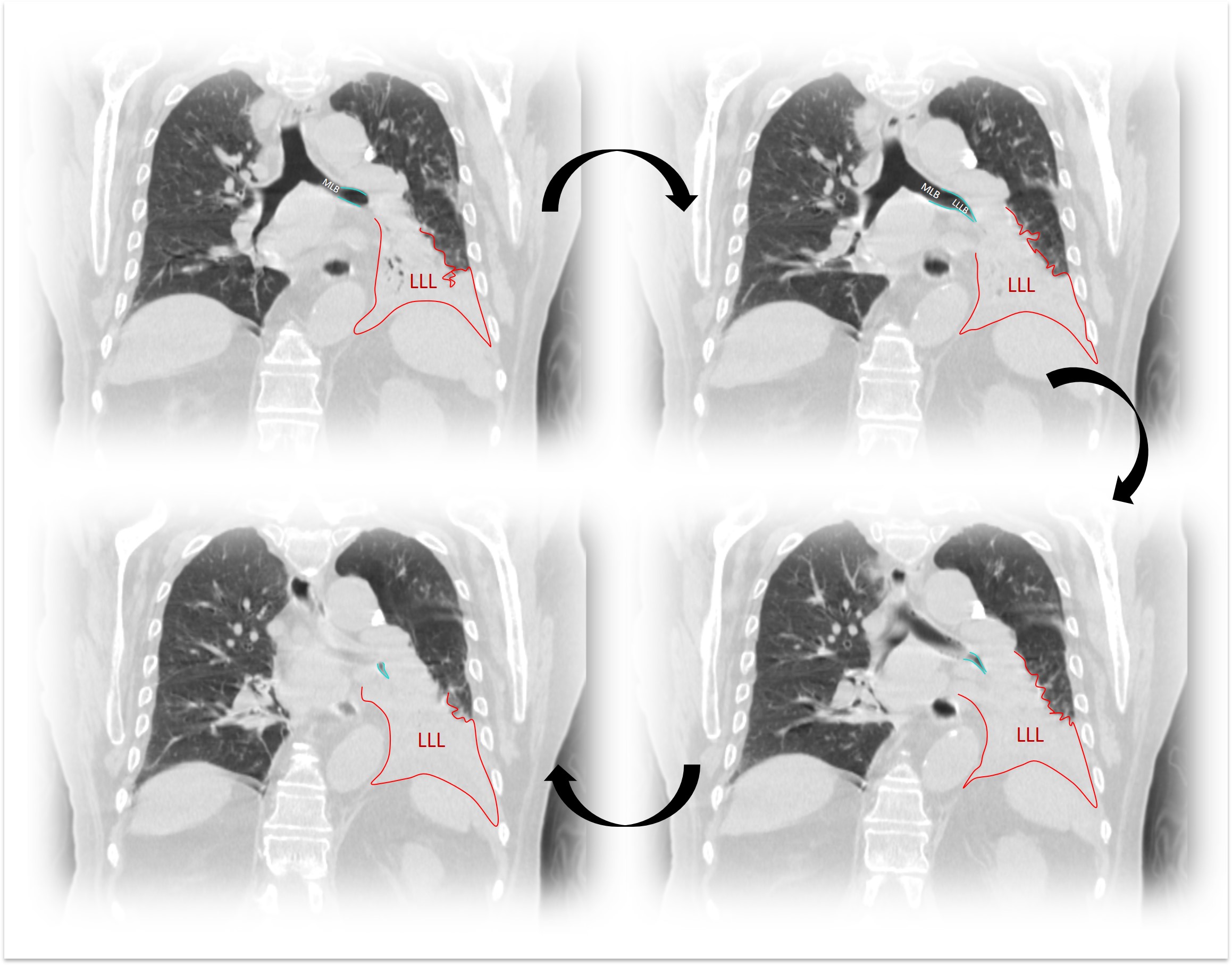

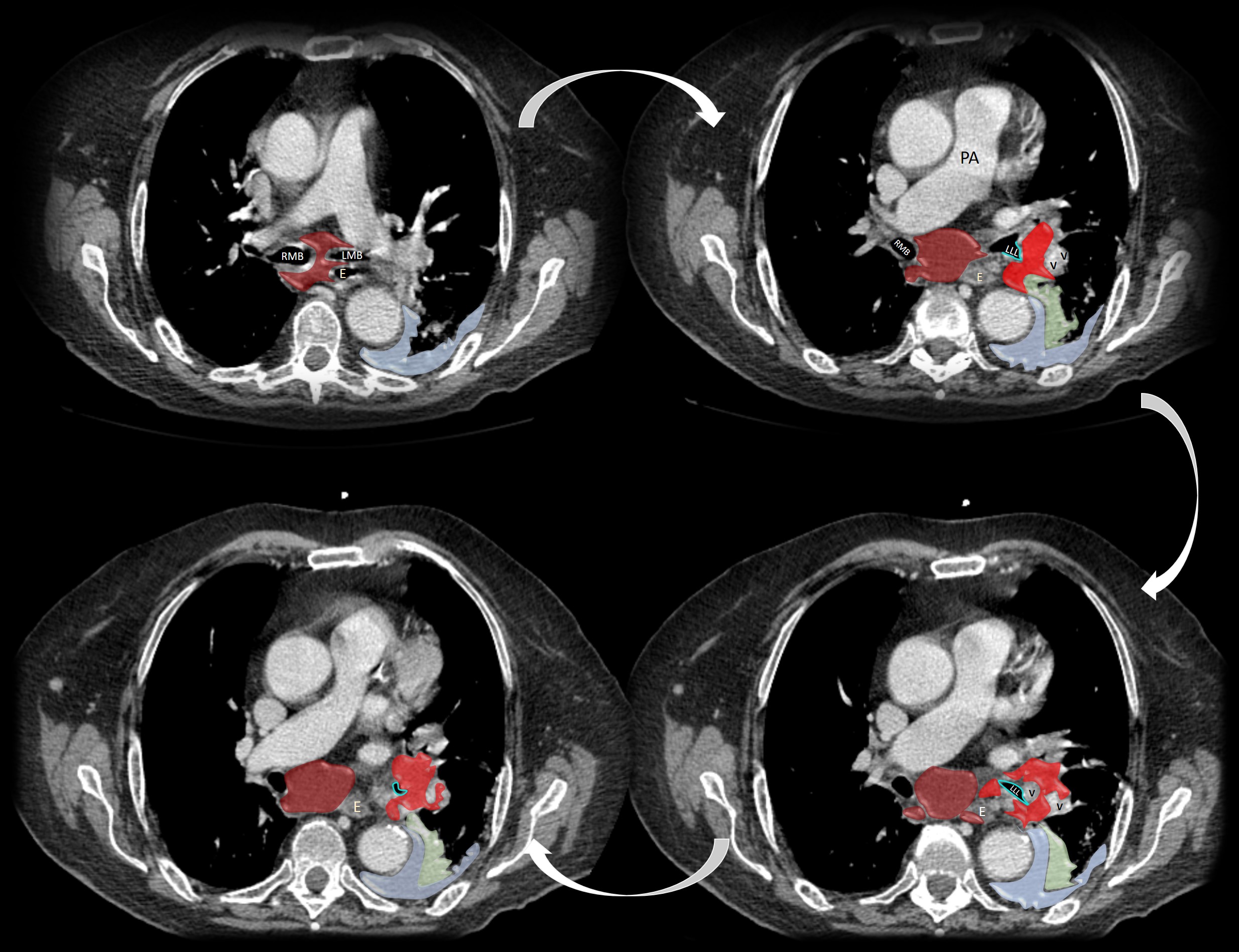

An ectopic ACTH production was confirmed by a failure of dexamethasone to suppress cortisol production (serum cortisol after 1 mg de dexamethasone: 67.5 mcg/dL; reference < 1.8 mcg/dL). Further brain imaging with MRI showed no signs of hypophyseal disease. A full body computerized tomography documented a 35 mm irregular mass in the left lung (hilum and lower lobe) with adjacent lymphadenopathy, suspicious of malignancy. (Fig’s. 1 and 2) Samples obtained via bronchial fibroscopy revealed a small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC). The final diagnosis was a SCLC with ectopic ACTH production and associated Cushing Syndrome (CS).

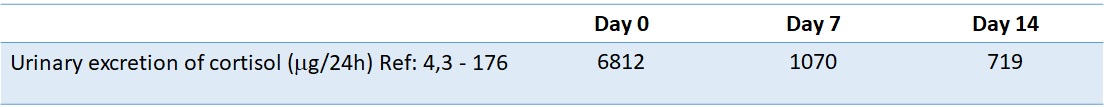

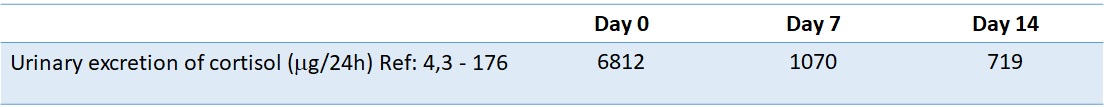

The patient was started on metyrapone (doses up titrating to a maximum 1500 mg) and over the course of 2 weeks a reduction in cortisol production was observed, with the following quantitation of urinary excretion of cortisol 719 mg/24h (previous 6812 mg/24h) (Fig. 3). Other adjunctive therapies were added, including intravenous potassium replacement, diuretics, combined anti-hypertensives and insulin. Citalopram and clonazepam were started after psychiatric evaluation. After a multidisciplinary evaluation, the tumour was deemed unresectable and cytoreductive chemotherapy was indicated upon clinical stability. There was a progressive worsening of the clinical status, with refractoriness to the aforementioned measures and the patient died due to complications of disease progression.

DISCUSSION

CS is a rare disorder with an incidence of 0.7-2.4 per million population per year, associated with high morbidity and mortality.1,2Ectopic production of ACTH is the second most frequent cause of CS (12%), frequently as a paraneoplastic syndrome, but on 8-20% are SCLC.2,3Considering the SCLC, CS is only present as paraneoplastic syndrome in 1.6-4.5% of the cases.3The clinical presentation is very variable, typically including progressing arterial hypertension, glucose intolerance, hyperlipidaemia and depression.1,2,4In this particular subtype of SCLC-associated CS the onset is described as more abrupt, generally with hypokalaemia, metabolic alkalosis and high risk of opportunistic infection as more prominent manifestations.4,5

SCLC initially manifested as a CS secondary to a paraneoplastic ACTH, as described in this case, is an uncommon occurrence.3,6]The diagnosis resulted from a thorough investigation of the aetiology of CS, starting with serum ACTH dosing followed by a dexamethasone test confirming an ectopic production. Further imaging and the bronchoscopy led to the final diagnosis of a SCLC.

According to the literature, the gold standard treatment consists in tumour removal (surgery or/and chemotherapy). Adrenal suppression may be started in a transition phase or in patients where surgery or chemotherapy are not indicated, in order to control the symptoms associated with CS.1,3,7The adrenal suppression may be achieved by supressing cortisol levels until normal values or a total blockage cortisol production followed by glucocorticoid replacement. Medical treatment includes drugs that inhibit steroidogenesis (ketoconazole, metyrapone or etomidate), modulate ACTH release (somotastatin and dopamine agonists) and blockage of glucocorticoid action at its receptor (mifepristone).3,4

In this particular case, there was a mild clinical improvement with the introduction of high metyrapone doses and supportive medical treatment. Unfortunately, this improvement was not enough to allow for cytoreduction chemotherapy to be initiated and the patient died due to disease progression, in line with the worse prognosis this association usually confers.4,5

CONCLUSION

CS is a rare condition and its correlation with a SCLC is even more uncommon. This case shows a rare presentation of a lung cancer, with a CS as the main clinical manifestation requiring a multidisciplinary approach to manage symptoms.

Figura I

Figure 1 - Blue: (MLB) Main left bronchus stenosis; Red: (LLL) Lower left lobe consolidation

Figura II

Figure 2 - E- Oesophagus; RMB – Right main bronchus; LMB – Left main bronchus; LLL – Left lower lobe; PA – Pulmonary artery; V- Pulmonary vein; Dark red: Multilevel mediastinal adenopathy; Blue: Left pleural effusion; Green: Consolidated lung; Light Red: Tumour.

Figura III

Figure 3 - Evolution of urinary excretion of cortisol with metyrapone therapy

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Sharma ST, Nieman LK, Feelders RA. Cushing´s syndrome: epidemiology and developments in disease management. Clin Epidemiol. 2015 Apr 17;7:281-93. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S44336.

2. Nieman, L. (2020) Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of Cushing´s syndrome. In A. Lacroix & K. A. Martin (Eds), UptoDate. Available from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-and-clinical-manifestations-of-cushings-syndrome?search=cushing%20syndrome&source=search_result&selectedTitle=4~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=4

3. Kanaji N, Watanabe N, Kita N, et al. Paraneoplastic syndromes associated with lung cancer. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5(3):197-223. doi:10.5306/wjco.v5.i3.197

4. Lynnette K. Nieman, Beverly M. K. Biller, James W. Findling, John Newell-Price, Martin O. Savage, Paul M. Stewart, Victor M. Montori, The Diagnosis of Cushing´s Syndrome: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 93, Issue 5, 1 May 2008, Pages 1526–40. Doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0125

5. Young, J., Haissaguerre, M., Viera-Pinto, O., Chabre, O., Baudin, E., & Tabarin, A. MANAGEMENT OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE: Cushing’s syndrome due to ectopic ACTH secretion: an expert operational opinion, European Journal of Endocrinology 2020, 182(4), 182, R29–R58. Doi: 10.1530/EJE-19-0877

6. Midthaun, D. (2020) Overview of the risk factors, pathology, and clinical manifestations of lung cancer. In Rogerio C. Lilenbaum & Sadhna R. Vora (Eds), UptoDate. Available from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-the-risk-factors-pathology-and-clinical-manifestations-of-lung-cancer?search=sclc%20paraneoplastic§ionRank=1&usage_type=default&anchor=H11&source=machineLearning&selectedTitle=1~150&display_rank=1#H546074787

7. Kasper, D., Hauser, S., Jameson, J., Fauci, A., Longo, D. and Loscalzo, J.. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 19th ed. United States of America: McGraw Hill; 2015. 2313-8 pp