Ludwig’s angina, first described in 1836, is a rapidly progressive and potentially life-threatening bilateral cellulitis of sublingual, submental and submandibular spaces, that spreads through contiguous tissue rather than lymphatics or hematogeneous. It mostly has odontogenic origin (70%-90% of cases)1 and is associated with various comorbidities, namely diabetes mellitus and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1,2 One of its possible complications is airway obstruction, and therefore it is often managed on an intensive care unit (ICU).3 Although the incidence is lowering with the improvement of medical care, physicians should be aware of this entity and treat it promptly. The diagnosis is clinical, and image exams should not delay the treatment. Treatment consists in empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics that cover oral flora pathogens and careful monitoring and management of the airway. If there is documentation of deep neck space abscesses, surgical incision and drainage is indicated. In selected patients, ultrasound-guided drainage can be an equally effective and less invasive alternative.4

Lemierre’s syndrome is a septic thrombophlebitis of the ipsilateral internal jugular vein subsequent to a local infection, typically precipitated by tonsillitis, peritonsillar abscess or dental infection in adults, or otitis media in children.1 It was first described in 1936, and it was associated with bacteremia and metastatic infections (in most cases, pulmonary abscesses).5 At that time, the causative identified organism was Bacillus funduliformis, later renamed Fusobacterium necrophorum, and more recent studies revealed that this organism was the etiologic agent in more than 80% of the cases of Lemierre’s syndrome. The aim is to the treat underlying infection, and anticoagulation is generally not recommended.1,6 Lemierre’s syndrome remains life-threatening, with about 17% of mortality rate.1 Recent data suggests that Fusobacterium necrophorum pharyngitis occurs as often as streptococcal pharyngitis in adolescents and young adults (under 30 years-old), and because of this potential severe complication, we should revise our paradigm for pharyngitis in these age groups, and, when treating empirically, we should use penicillins or cephalosporins, avoiding macrolides.5

Descending necrotizing mediastinitis, a rare complication of Ludwig’s angina, is an acute, severe, rapidly progressive condition, with high mortality rate (30-50%), resulting from spread of the infection into the retropharyngeal space and the superior mediastinum. This entity is typically caused by several agents, in which anaerobes generally outnumber aerobes. The most common are: Prevotella, Peptostreptococcus, Fusobacterium, Veillonella, Actinomyces, and oral Streptococcus, and broad-sprectrum antibiotics, such as Piperacilin/Tazobactam should be initiated promptly, but surgical drainage is the definitive treatment.1

Case Description

33-year-old woman, with history of smoking and multiple dental cavities and infections, who experienced, for several weeks, odontalgia and progressive mouth opening restriction. She went to the emergency room of her hospital and was discharged with prescription of antibiotic (amoxicillin/clavunalate).

As the symptoms worsened, she returned to the emergency room three days later, where she presented severe trismus (< 1 cm of mouth opening), swelling and hyperemia of buccal mucosa and floor of mouth (worsened on left side), with no signs of tonsillitis, painful swelling of submental, left submandibular and left anterior cervical areas.

Methods and Procedures

She had elevated inflammatory parameters: leukocytosis 14,600/mm3 with neutrophilia 92.3%, and C-reactive protein 377 mg/L (<5 mg/L), and also mild thrombocytopenia (128,000/uL). Cervical computed tomography (CT) showed multiple communicating facial and cervical abscesses, namely on bilateral sublingual, submandibular and submental, right pterigomandigular, left lateropharingeal, and retropharyngeal spaces. No collections on the mediastinum were observed at this point.

She was transferred to our tertiary hospital for Maxillofacial Surgery care, where she underwent urgent surgery (bilateral drainage of the pterigomandibular, submental, sublingual, laterapharingeal and retropharyngeal spaces), maintained the nasotracheal tube for airway protection (she was not dependent of mechanical ventilation), and was then admitted to ICU, where she continued amoxicillin/clavulanate (2200 mg q8h).

Three days after surgery, she was clinically stable but the new image evaluation documented persistence of an extensive retropharyngeal abscess communicating with submandibular and vascular spaces, additionally associated with a thrombus of the left jugular vein (Fig’s 1, 2 and 3). At this point, extension to the posterior mediastinum and bilateral pleural effusion was also observed (Fig’s 4 and 5).

She underwent a second urgent procedure with combined approaches from Maxillofacial and Thoracic Surgery teams, for surgical drainage of the infected areas: revision drainage of left lateropharingeal, retropharingeal and bilateral pterygomandibular spaces, and drainage of the right submasseteric space; bilateral thoracic drainage of abundant purulent collections, extending to the posterior mediastinum and retroesophageal space from the apex to thediaphragm.

Specimens from the cervical and thoracic collections were both sent for microbiologic analysis.

The microbiological samples isolated beta-lactamase positive Prevotella denticola on both cervical and pleural effusion samples and Streptococcus constellatus on hemoculture and pleural effusion.

Infective serologies, including HIV, were negative.

The antibiotics were changed to piperacillin/tazobactam and clindamycin accordingly to antibiotic susceptibility test and also synergic effect.

Because of thrombosis of jugular vein, although of septic etiology, she was started on enoxaparin on therapeutic dosis, due to its extension.

She spent 16 days on ICU and was extubated on 15thday. Total in-hospital stay duration was 36 days.

Antibiotics were maintained for a total of 32 days, with clinical, analytical and radiological improvement. The left jugular vein remained collapsed and, after consulting with Vascular Surgery, it was decided to maintain anticoagulation for three months until repeated cervical Doppler ultrasound evaluation.

After hospital discharge, she was referred to the Oral Medicine department for completion of oral cavity treatment and rehabilitation.

She abandoned, by her choice, our clinical follow-up.

Discussion

The present case is a typical presentation of Ludwig’s angina in a young immunocompetent patient without relevant comorbidities, but with a major risk factor: poor dental hygiene and care, which leads to the main cause of that entity: dental infection.

The length of symptoms (several weeks) and progressive mouth opening limitation should have raised red flags at first medical evaluation.

Although initially she had no signs of airway obstruction, because of its extension and progression despite empirical antibiotic therapy, it was decided to perform an urgent surgery.

On the postoperative CT, an extensive thrombus of left jugular vein was documented, which, associated with previous known local infection, lead to the diagnosis of Lemierre’s syndrome.

The same CT showed the persistence of abscesses, despite surgical drainage, extending to the posterior mediastinum, by a contiguous spread mechanism, suggestive of a descending necrotizing mediastinitis, and so she would need additional urgent surgery, which is the definitive treatment.

The microbiological isolates (Prevotella denticola and Streptococcus constellatus) are consistent with the diagnosis, since they are common bacteria of oral flora.

The initial choice of empirical antibiotic covered oral flora, including anaerobes. Penicillins, cephalosporins, metronidazole and clindamycin are reasonable choices in this context (but metronidazole alone should be avoided).1 However, in cases of infectious progression, antibiotic resistance should be suspected and escalation to larger broad-spectrum antibiotics should be considered. The microbiological isolates were determinant to adjust antibiotic therapy.

In some cases of Ludwig’s angina surgical drainage is required, depending on its extension, but as if it progresses, like in this case, with descending necrotizing mediastinitis, the surgical treatment is mandatory.1

Despite of absence of Fusobacterium necrophorum isolates, we still consider Lemierre syndrome diagnosis, which can be related with another bacteria, in a smaller number of cases. Besides, classically this entity is associated with metastatic infection resulting from septic emboli from internal jugular vein thrombophlebitis (not seen in this case, probably because of current antibiotic therapy), and has typical symptoms, such as oropharyngeal pain, fever, neck swelling and arthralgias1, which were not present in this case as well, but their presence needs to be always assessed.

Even though the use of anticoagulation is not regularly recommended in Lemierre’s syndrome1,6, because of potentially higher likelihood of causing septic emboli1, the extension of the thrombosis and the absence of improvement with the treatment, lead us to the decision of initiating and maintaining it, with close clinical and imagiological monitoring.

This is a case of great severity, requiring two major surgical interventions, a longer antibiotic therapy and also prolonged intubation for airway protection, due to its complications.

In our country, the national health system does not provide effective and widespread dental care and the majority of these services are private. Therefore, the financially vulnerable citizens, which seems to be this case, have no access to oral health, and hence are more susceptible to this kind of complications.

Our governmental structures should weigh up pros and cons of an integrated oral health care system, considering clinical cases like this one, with steep health resources’ consumption and a non-negligible rate of complications and mortality.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank to Dr. Patrícia Freitas, Dr. Paulo Correia and Dr. José Maria Barros (Radiology Department) for their help at selecting and interpreting CT scans.

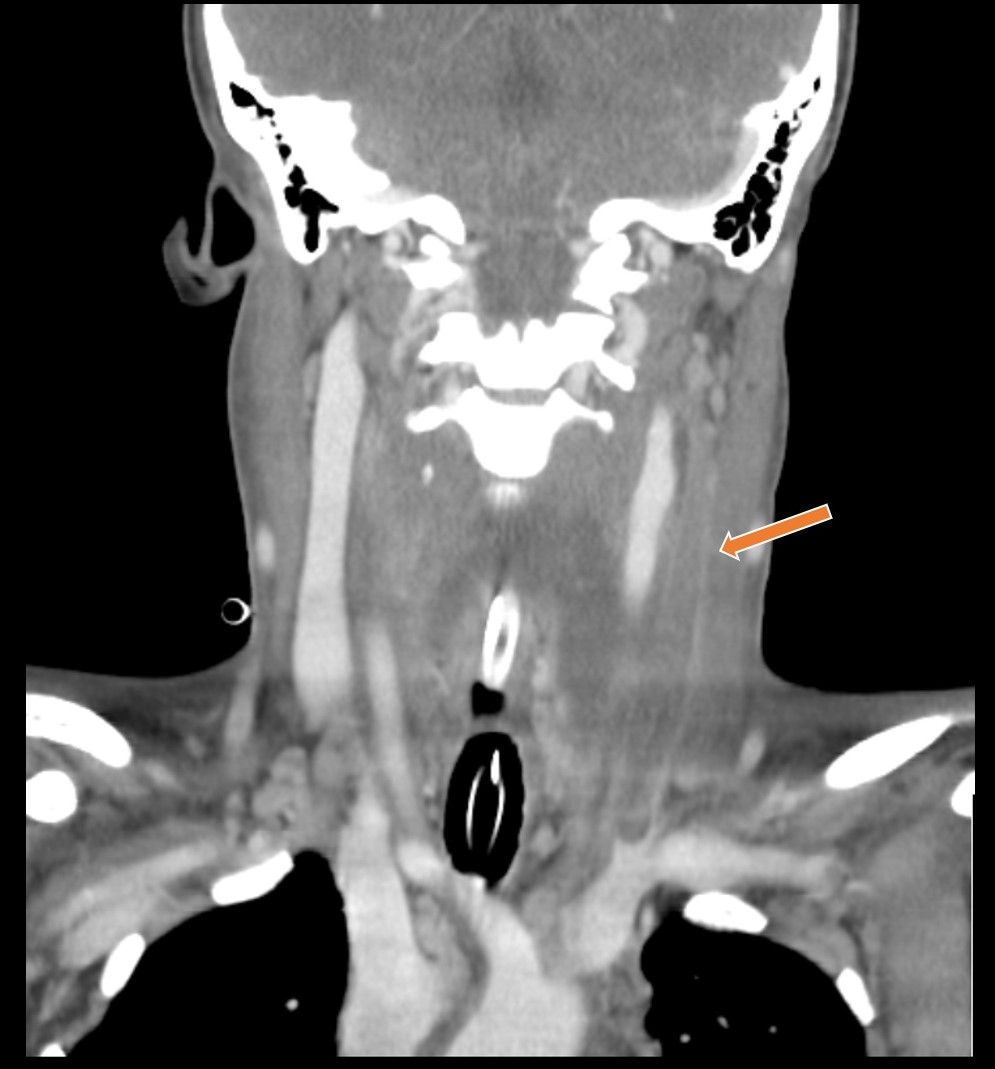

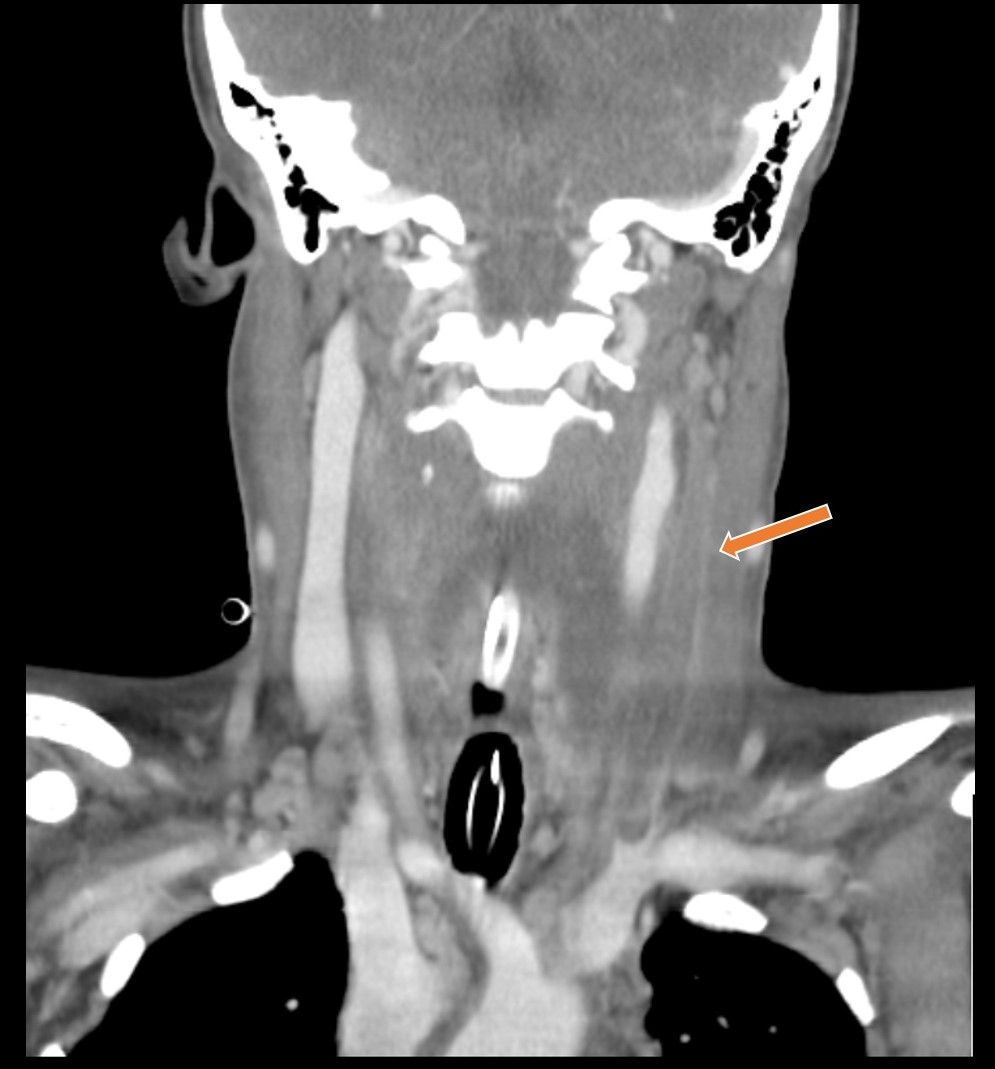

Figura I

Thrombus on the left jugular vein - arrow (CT, coronal view).

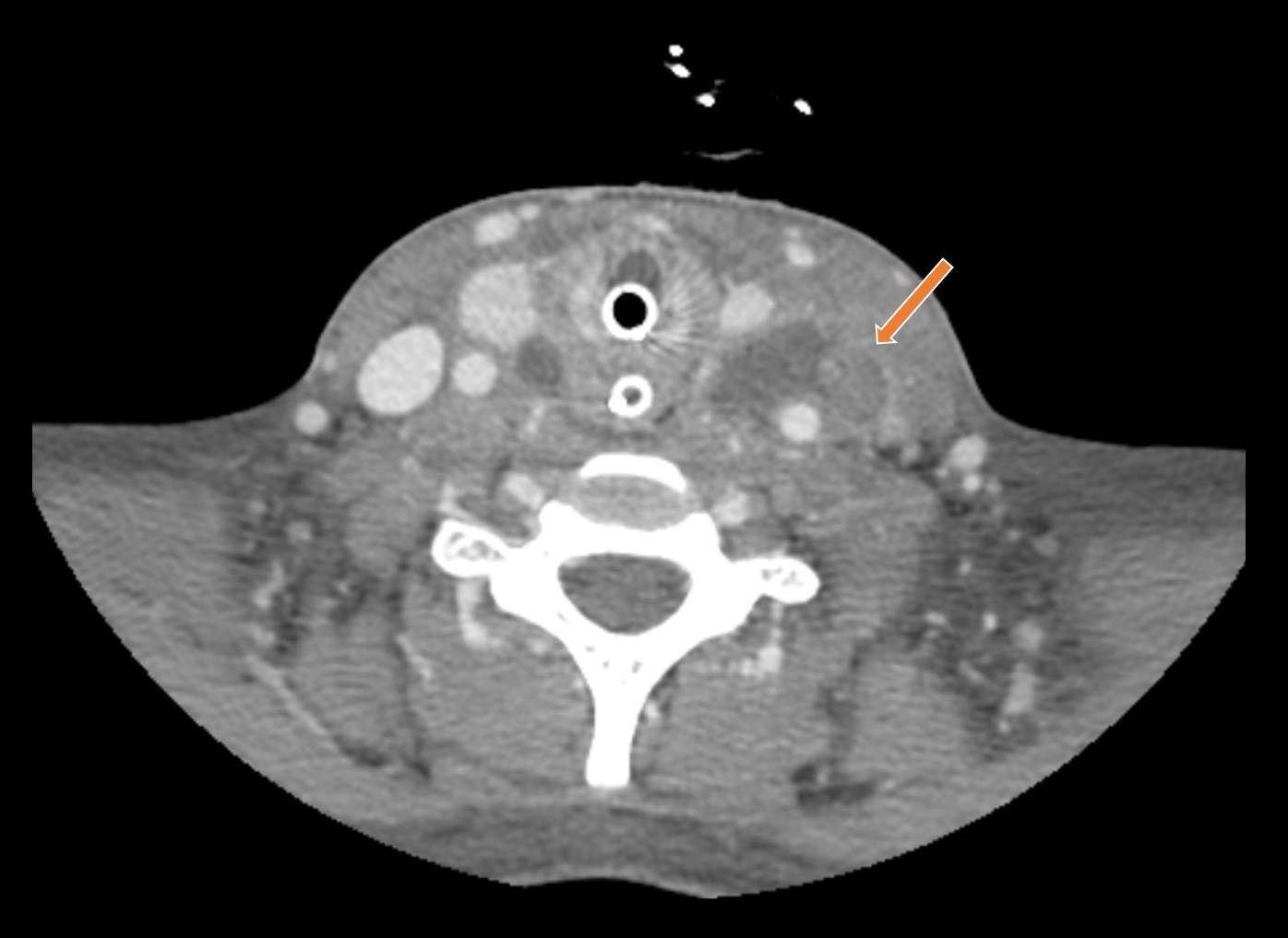

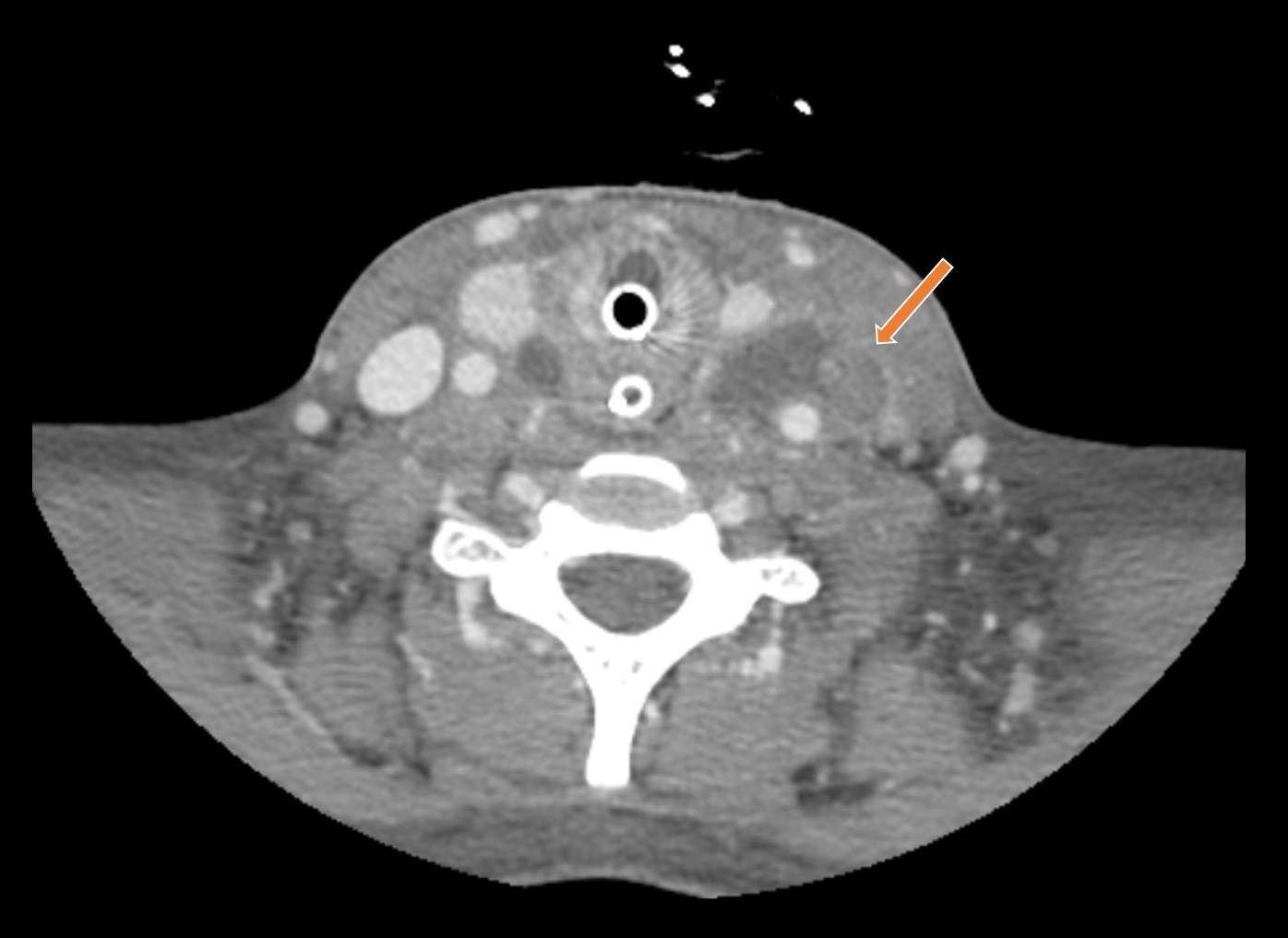

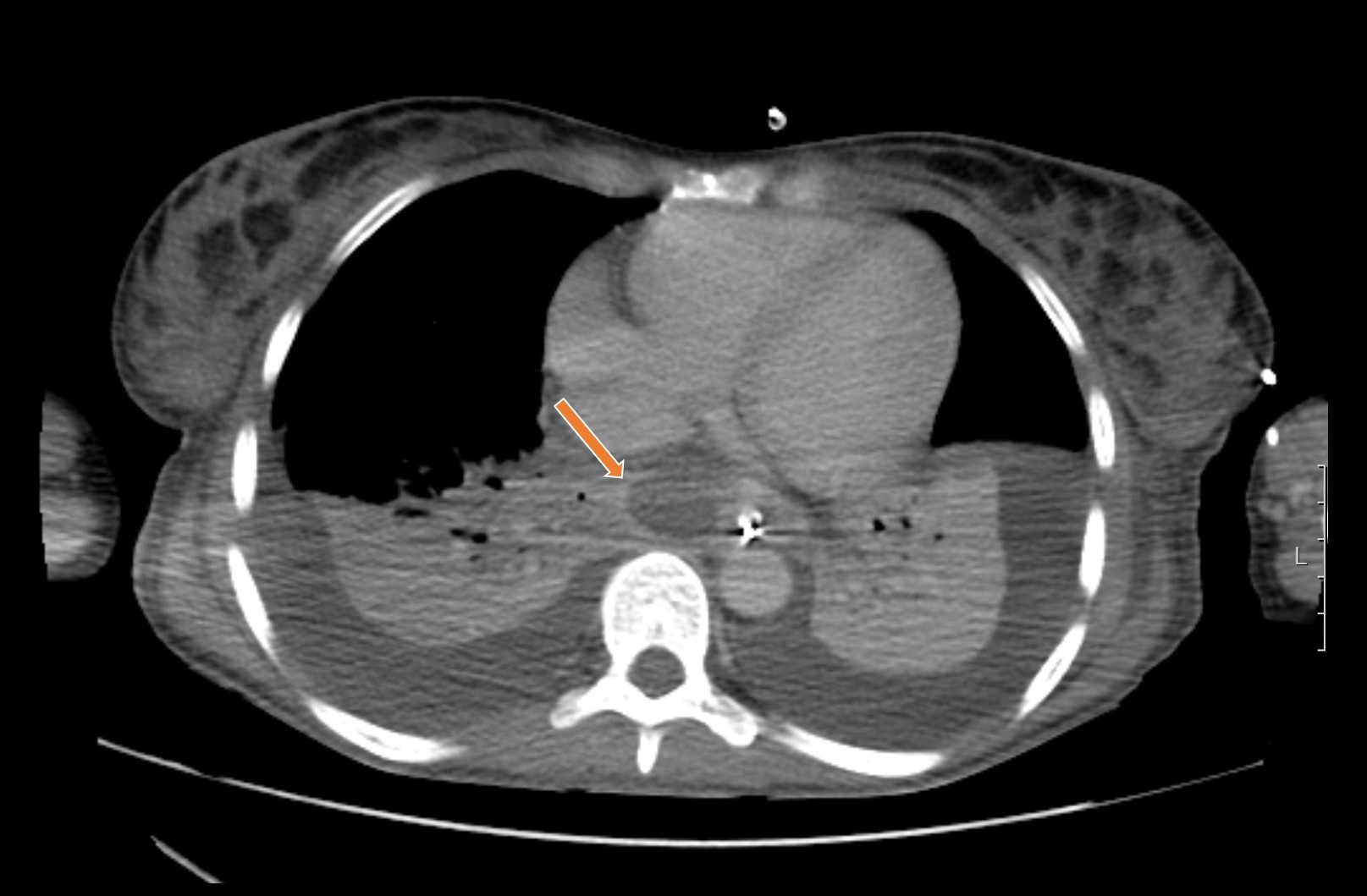

Figura II

Thrombus on the left jugular vein - arrow (CT, axial view).

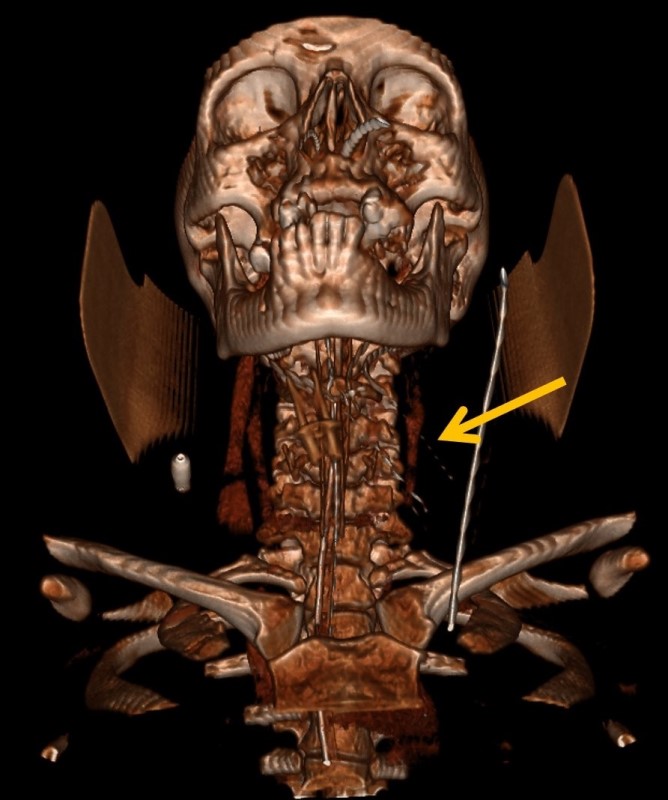

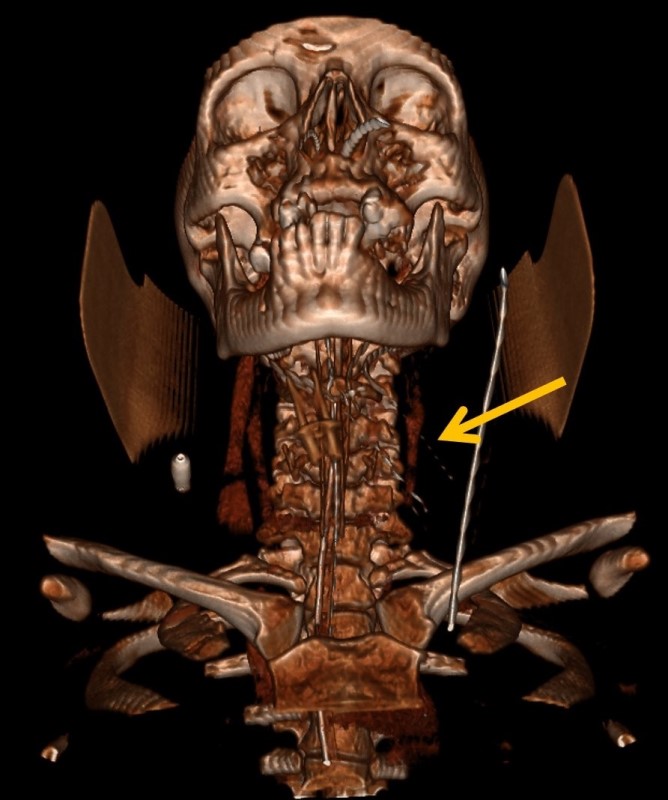

Figura III

Thrombus on the left jugular vein - arrow (CT-3D reconstruction).

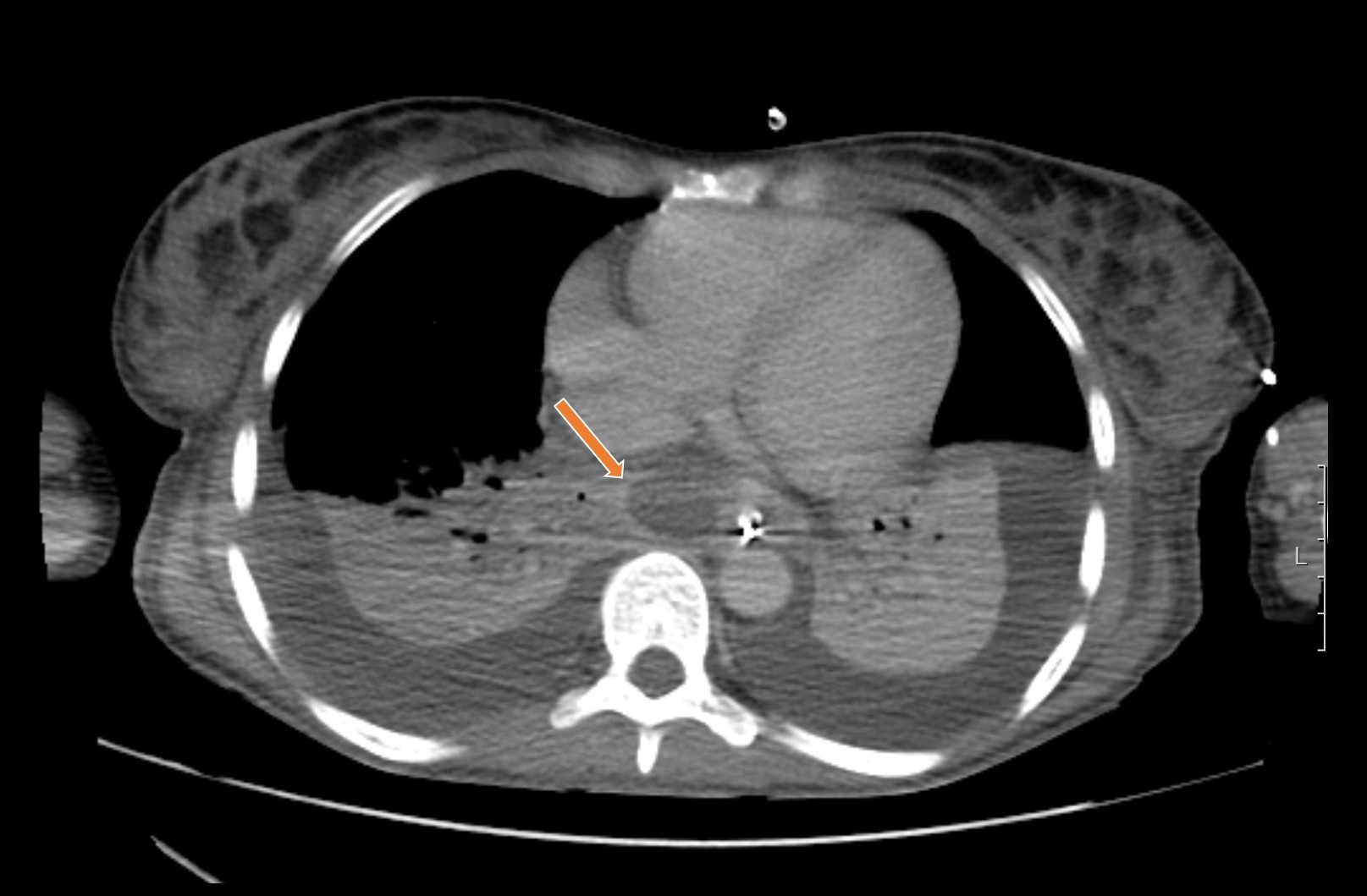

Figura IV

Extensive abscess in posterior mediastinum (arrow) and bilateral pleural effusion (CT, axial view).

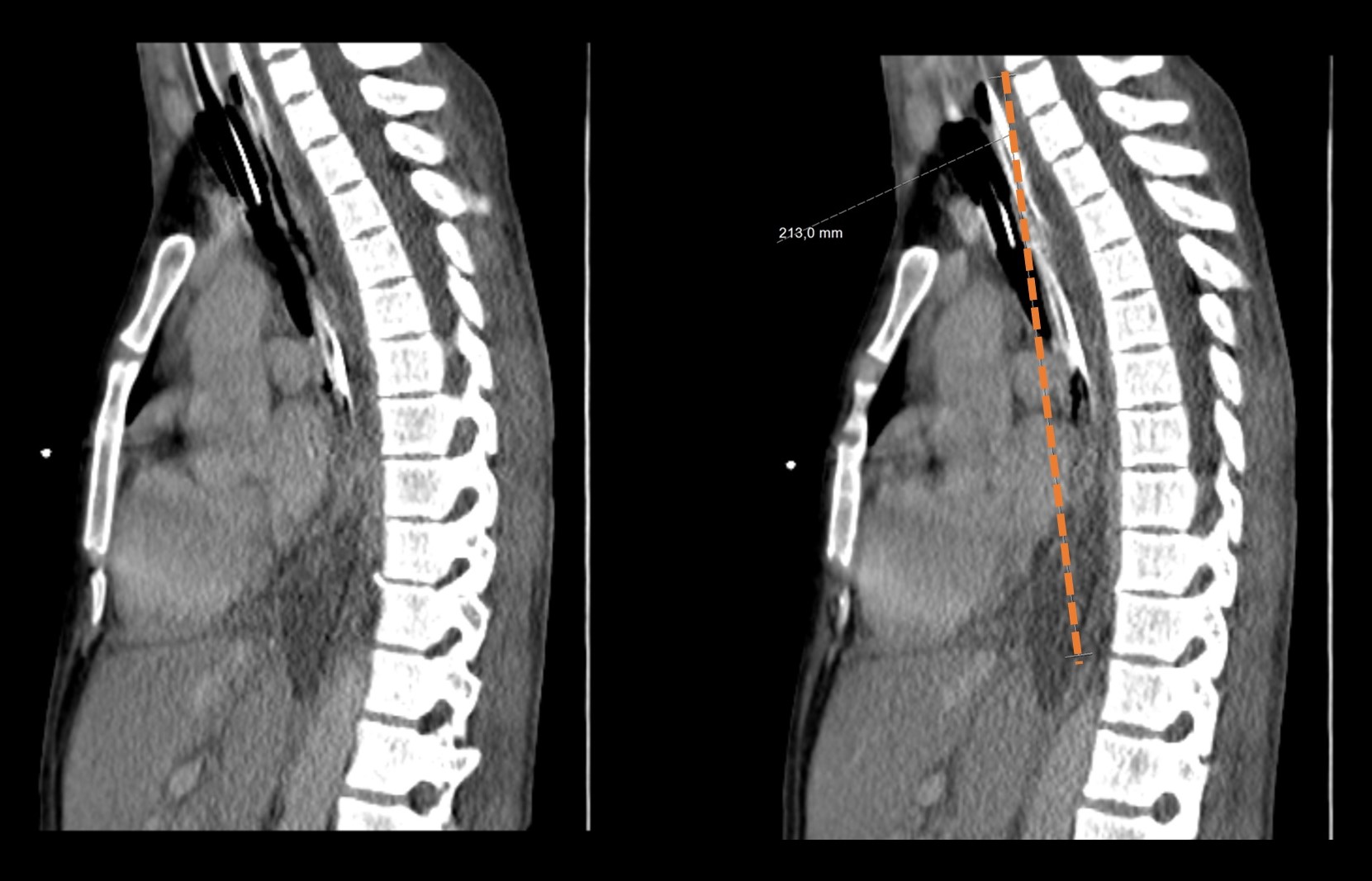

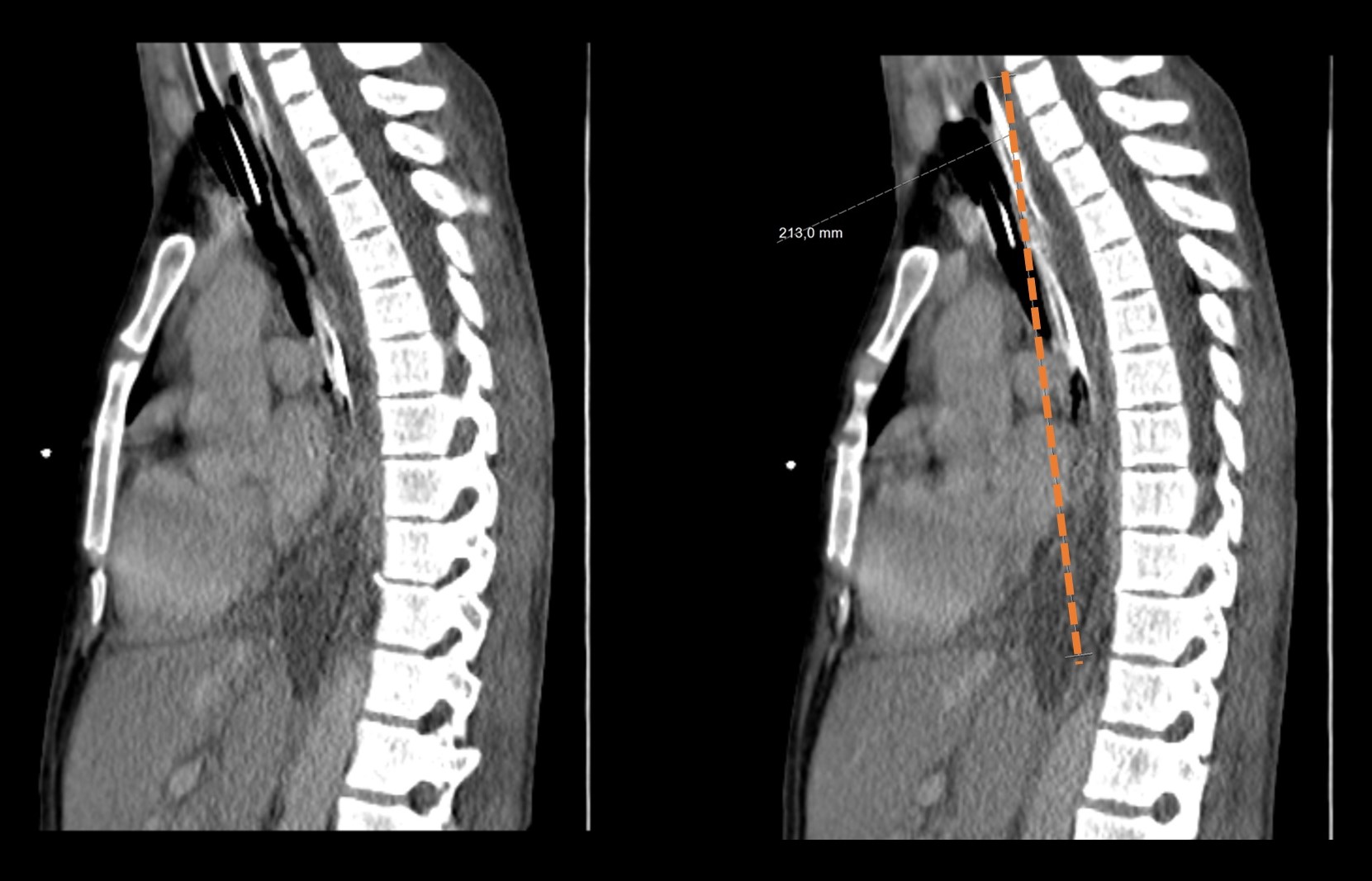

Figura V

Extensive abscess in posterior mediastinum, affecting danger space, from T4 to diaphragm - dashed line (CT, sagittal view).

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1) Li RM, Kiemeney M. Infections of the Neck. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2019 Feb;37(1):95–107.

2) Botha A, Jacobs F, Postma C. Retrospective analysis of etiology and comorbid diseases associated with Ludwig’s Angina. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2015;5(2):168–73.

3) Amian A, Turner E. Across All Planes: Ludwig’s Angina, Lemierre Syndrome, & Acute Descending Necrotizing Mediastinitis. Crit Care Med. 2013 Dec;41(12):A303.

4) Dabirmoghaddam P, Mohseni A, Navvabi Z, Sharifi A, Bastaninezhad S, Safaei A. Is ultrasonography-guided drainage a safe and effective alternative to incision and drainage for deep neck space abscesses?. J Laryngol Otol. 2017 Mar;131(3):259-263.

5) Centor RM. Expand the Pharyngitis Paradigm for Adolescents and Young Adults. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Dec;151:812-815.

6) Campo F, Fusconi M, Ciotti M, Diso D, Greco A, Cattaneo CG, et al. Antibiotic and Anticoagulation Therapy in Lemierre’s Syndrome: Case Report and Review. J Chemother. 2019 Feb;31(1):42–8.