INTRODUCTION Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (KFD) also known as histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis is a benign, self-limited condition usually characterized by tender cervical lymphadenopathy, mild fever and night sweats. It is a rare disease in Europe, with higher prevalence among Japanese and other Asiatic individuals. It typically affects adults younger than 40 years and a female preponderance has been underlined in literature (4:1 ratio) although recent reports indicate that the actual gender ratio is closer to 1:1.1

Systemic involvement has rarely been described in KFD (skin rash, arthritis, oral ulcers, hepatomegaly and splenomegaly).1-5

Numerous causes such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV),6-9 parvovirus B19,9 human T-cell lymphotropic virus,9 among other agents, have been proposed. Moreover, it has a well-recognised association with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).1-5,10 Nevertheless, the aetiology of this disorder remains unknown.5

A node biopsy should be performed in order to achieve diagnosis2,3,11 and most importantly, to exclude other conditions (namely lymphoma), which require directed aggressive treatment1,6. Characteristic histological findings include distortion of the normal architecture with cortical and paracortical nodules with coagulative necrosis and abundant apoptotic Karyorrhectic debris.1-3,11

It usually has a benign and self-limited course, resolving spontaneously within 1 to 4 months. A relatively low recurrence rate (3-7%)1,2,4,5 and few fatal cases have been described.12 There is no targeted treatment but corticosteroids may be used in severe extranodal and systemic KFD.1,2

CLINICAL REPORT: 20-years-old woman, with no relevant medical history presented with painful right cervical mass. Physical examination revealed a single, tender, elastic, non-adherent nodule measuring 1.5 cm in the right posterior cervical lymphatic chain and a hepatomegaly. Blood tests were unremarkable except for a positive for EBV-VCA Ig M, suggesting an acute infection. Although the clinical features suggested a benign aetiology, a CT-scan was done and showed multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the cervical region. A node biopsy demonstrated numerous secondary lymphoid follicles and prominent expansion of the paracortical area at the expense of small lymphocytes and many immunoblasts – histological characteristics favouring reactive lymphadenitis. In addition, mycobacterial testes were negative. The diagnosis of EBV lymphadenitis was made and the patient treated with non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs. A CT-scan 6 months later showed no lymphadenopathies.

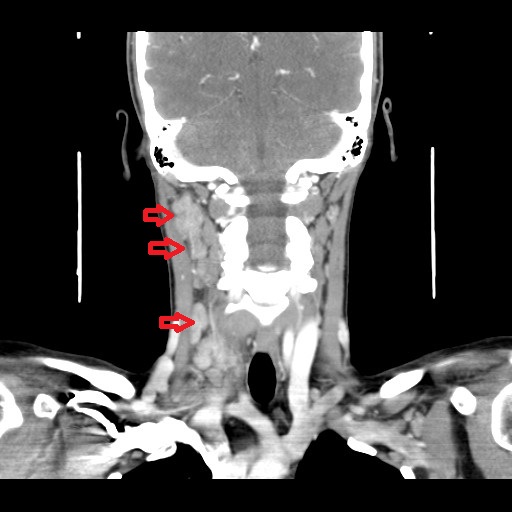

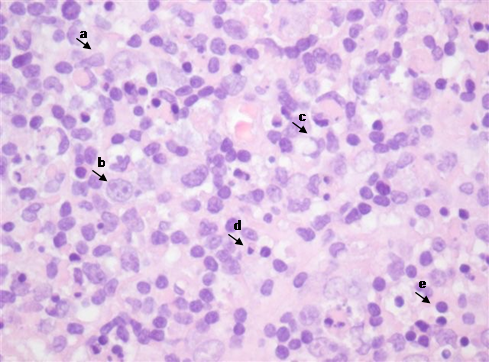

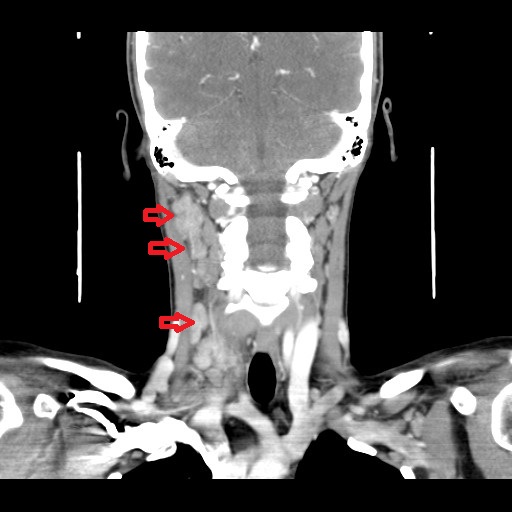

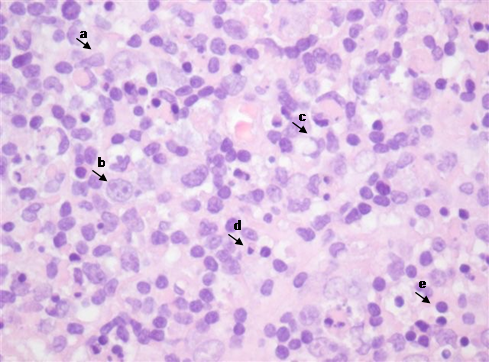

One year later, she developed another cervical tender, elastic adenopathy, this time associated with fever, stomatitis and hepatomegaly. Physical examination confirmed the presence of multiple cervical enlarged lymph nodes bilaterally predominantly in the right side. Blood tests revealed lymphopenia (730x109/uL), thrombocytopenia (131000x109/uL) and previous contact/immunization to rubella, parvovirus B19 and HBV. EBV re-infection/chronic infection and LES were also excluded through serologic tests: EBV - VCA IgM and EA IgG negative; sedimentation rate 17 mm/h [normal range < 16mm/H]; antinuclear antibodies, anti-dsDNA antibodies and anti-Smith antibodies were all negative. CT-scan allowed identification of multiple lymphadenopathies in the jugular intern, spinal and jugular-carotid chains with diffuse areas of necrosis, predominantly on the right side (Fig. 1). Another excisional lymph node biopsy was performed. Histology revealed the presence of parafollicular hyperplasia (T zone) and sinus histiocytosis; nodular polymorphic infiltrate composed of abundant histiocytes, some foam cells, monocytoid cells, plasmacytoid dendritic cells, activated lymphocytes and immunoblasts with frequent isolated cell necrosis, caryorrhexis and abundant apoptotic bodies. Monocytoid and histiocytic cells predominate with co-expression of CD 68 and myeloperoxidase and activated CD3 + lymphocyte (Fig. 2). The hystological findings coupled with stomatitis and cytopenias, suggested the diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease with extranodal involvement. Treatment with corticosteroid (2 months of prednisolone 40mg/day and progressive weaning) resulted in complete resolution. The Patient remains asymptomatic after a 5-year follow-up period.

DISCUSSION Physical examination is crucial for an accurate assessment of lymph nodes, since hard and immobile ones suggest malignant causes, whereas the opposite features point to benign aetiologies. Moreover, it is essential to evaluate their location, which may be useful in guiding further investigation.

The differential diagnosis of lymphadenopathies includes infections (mycobacterial, viral and bacterial agents), haematological/oncological malignancies (namely lymphoma and metastatic carcinoma) and autoimmune disorders. Since the patient presented in the first place with reactive lymphadenitis to primary EBV infection, when she developed, one year later, another lymphadenopathy associated with cytopenia, it was vital to exclude EBV-associated conditions,14 namely re-infection, chronic active EBV infection (CAEBV),8,9,13,14 KFD and lymphoproliferative cancers. CAEBV and KFD share many clinical features - fever, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, hepatitis or cytopenia.13 While KFD is diagnosed based on biopsy, CAEBV infection is defined by specific criteria - illness lasting at least 6 months, increased EBV level in either the tissue or the blood, and lack of evidence of a known underlying immunodeficiency,9,13 which were not present in our patient. EBV is an oncogenic virus, thus lymphomas are a feared complication diagnosed by microscopic examination of tissue morphology.14 No association between KFD and malignant lymphoma has been reported.15

In this case, excisional biopsy was essential for diagnosis as it revealed characteristic histopathologic findings of KFD such as irregular paracortical areas of coagulative necrosis with abundant karyorrhectic debris, and a large number of different types of histiocytes at the margin of the necrotic areas. Neutrophils were characteristically not present and plasma cells were absent or scarce.15

KFD was first described in 1972 by Kikuchi, Fujimotoet aland three histopathologic stages have been reported.1,15 The proliferative stage recognized by the presence of various histiocytes, plasmacytoid monocytes and lymphoid cells containing karyorrhectic fragments and eosinophilic apoptotic debris; the necrotizing stage where various degrees of coagulative necrosis exists and the xanthomatous stage manifested with foamy histiocytes.4,11 The immunophenotype of KFD consists of a predominance of T-cells, with very few B-cells and there is an abundance of CD8+ T-cells over CD4+ T-cells.1-3,11

While the pathogenesis of KFD is still unknown, some authors hypothesized that it may reflect a self-limited autoimmune condition induced by virus infected transformed lymphocytes.1,15,16 EBV is one of the viruses more frequently associated with KFD15 and some authors suggest that an initial lymphoproliferative phase with increased numbers of EBV-infected cells would give way to an hyperimmune necrotizing response with cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated killing of EBV-infected cells, engulfment by histiocytes and finally a xanthomatous reparative phase.6,8,15 That seemed to be the case in this patient.

KFD is typically self-limited within 1 to 4 months and supportive measures are the mainstay of therapy, but in this case, the patient was started on corticoids because she presented extranodal involvement. A low but possible recurrence rate of 3 to 4% has been reported over a period of 2 to 14 years following initial presentation.1,3 Few fatal cases have been described.12

Patients with KFD typically have negative autoimmune studies, but the association between KFD and LES has been reported with a frequency greater than that expected by chance alone and some authors have postulated that KFD may be an incomplete phase of lupus lymphadenitis.2,4

Although an infectious aetiology has been postulated, a definitive causative agent has not yet been found. It may thus be possible that KFD occurs as an immune phenomenon such as in the setting following acute EBV infection while in other cases it may be an early stage of SLE. KFD has a benign outcome, responds well to symptomatic treatment and should be included in the differential diagnosis of “lymph node enlargement”.

Figura I

Cervical CT-scan showing multiple adenopathy in the internal jugular, spinal and jugular-carotid chains predominantly on the right side.

Figura II

Lymph node histology: a-monocytoid cells; b-immunoblasts; c-histiocytes; d-plasmacytoid dendritic cells; e-activated lymphocytes; f-karyorrhexis, g-detritus bodies; h-apoptotic bodies.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Bosch X, Guilabert A. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:3–5. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-1-18.

2. Bosch X, Guilabert A, Miquel R, et al. Enigmatic Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: A comprehensive review. Am J Clin Pathol 2004;122:141–52. doi:10.1309/YF081L4TKYWVYVPQ.

3. Pepe F, Disma S, Teodoro C, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: A clinicopathologic update. Pathologica 2016;108:120–9.

4. Hutchinson CB, Wang E. Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2010;134:289-93. doi: 10.1043/1543-2165-134.2.289.

5. Song JY, Lee J, Park DW, et al. Clinical outcome and predictive factors of recurrence among patients with Kikuchi’s disease. Int J Infect Dis 2009;13:322–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2008.06.022.

6. Yen A, Fearneyhough P, Raimer SS, Hudnall SD. EBV-associated Kikuchi´s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis with cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol . 1997;36(2 Pt 2):342-6. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80413-6.

7. Hudnall SD, Chen T, Amr S, Young KH, Henry K. Detection of human herpesvirus DNA in Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease and reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. Int J Clin Exp Pathol . 2008;1(4):362-8.

8. Stéphan JL, Jeannoël P, Chanoz J, Gentil-Përret A. Epstein-Barr virus-associated Kikuchi disease in two children. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol . 2001;23(4):240-3. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200105000-00012.

9. Chiu CF, Chow KC, Lin TY, et al. Virus infection in patients with histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis in Taiwan. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus, type 1 human T-cell lymphotropic virus and parvovirus B19. Am J Clin Pathol 200;113:774-81. doi: 10.1309/1A6Y-YCKP-5AVF-QTYR.

10. Sanpavat A, Wannakrairot P, Assanasen T. Necrotizing non-granulomatous lymphadenitis: A clinicopathologic study of 40 Thai patients. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2006;37:563–70.

11. Deaver D, Horna P, Cualing H, Sokol L. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease. Cancer Control 2014;21:313-21. doi: 10.1177/107327481402100407.

12. Chan JK, Wong KC, Ng CS. A fatal case of multicentric Kikuchi´s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis. Cancer 1989; 63:1856-62. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900501)63:9<1856::aid-cncr2820630933>3.0.co;2-#.

13. Kimura H, Cohen JI. Chronic active Epstein-Barr virus dissease. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:1867. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01867.

14. Fugl A, Andersen, CL. Epstein-Barr virus and its association with disease - a review of relevance to general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20:62. doi: 10.1186/s12875-019-0954-3.

15. Hudnall SD. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: Is Epstein-Barr virus the culprit? Am J Clin Pathol 2000;113:761–4. doi:10.1309/N4E2-78V9-QTFH-X4FF.

16. Rosado FGN, Tang YW, Hasserjian RP, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto lymphadenitis: Role of parvovirus B-19, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6, and human herpesvirus 8. Hum Pathol 2013;44:255–9. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2012.05.016.