INTRODUCTION:

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disorder of unknown aetiology characterized by a T-helper response in which CD4 lymphocytes and activated macrophages accumulate in affected organs, resulting in formation of granulomas.1 Global prevalence is estimated at 10-20 per 100.000 population.2 Sarcoidosis can affect individuals at all ages, but most commonly affects those under 50 years old. It is more frequent in females and in African Americans. Mortality is estimated at 2-4% of cases, usually related to lung fibrosis and respiratory failure.1

Over 90% of patients develop lung lesions, and pulmonary disease accounts for most of the morbidity and mortality associated with this disease. Eyes, lymph nodes, and skin are the next most common locations, but any organ can be affected by sarcoidosis.3 Extrapulmonary manifestations can be subtle but contribute to significant morbidity.4 Aberrant calcium metabolism is associated with sarcoidosis and other granulomatous diseases, presenting most commonly with hypercalciuria. Symptomatic hypercalcemia is rare and only seen in less than 5% of patients.5 Bone marrow sarcoidosis represents an uncommon manifestation of extrapulmonary sarcoidosis.4 Although haematological abnormalities such as anaemia and leukopenia are expected, bone marrow involvement can present with normal haematological parameters.6

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 65-year-old caucasian woman presents with a four-month history of fatigue, anorexia, nausea, unprovoked weight loss of about 10 Kg and confusion. She had history of systemic arterial hypertension and chronic depression medicated with enalapril/hydrochlorothiazide 20mg/12.5mg and sertraline 50mg. She denied night sweats, fever, dysuria, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, or others. She had pale skin and mucous membranes, was slightly dehydrated, had normal vital signs and there were no palpable lymphadenopathies or organomegalies.

Blood tests (all described at Table 1) showed a new onset anaemia (haemoglobin of 10.9g/dL), lymphopenia (count of 600/μL), acute kidney injury (creatinine 3.4mg/dL and blood urea nitrogen 141mg/dL) and a markedly elevated serum calcium level of 16,6 mg/dL (corrected to 16.92mg/dL). Previous recent renal function was normal. Urinalysis showed calcium oxalate crystals. Intensive hydration was promptly initiated jointly with a bisphosphonate, as well as corticoid therapy due to multiple myeloma suspicion. Further haematological studies revealed low iron and iron saturation and normal transferrin, total iron binding capacity and ferritin. Beta-2 microglobulin was elevated but serum and urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation were normal. As these findings were against our first hypothesis of multiple myeloma, corticoids were discontinued after three days. Regarding hypercalcaemia, parathyroid hormone (PTH) and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels were low (4.0pg/mL and 10.7ng/mL, respectively) and 1.25 dihydroxyvitamin D level was elevated (75,0pg/mL); PTH related protein (PTHrp) was indetectable and hypercalciuria was present.

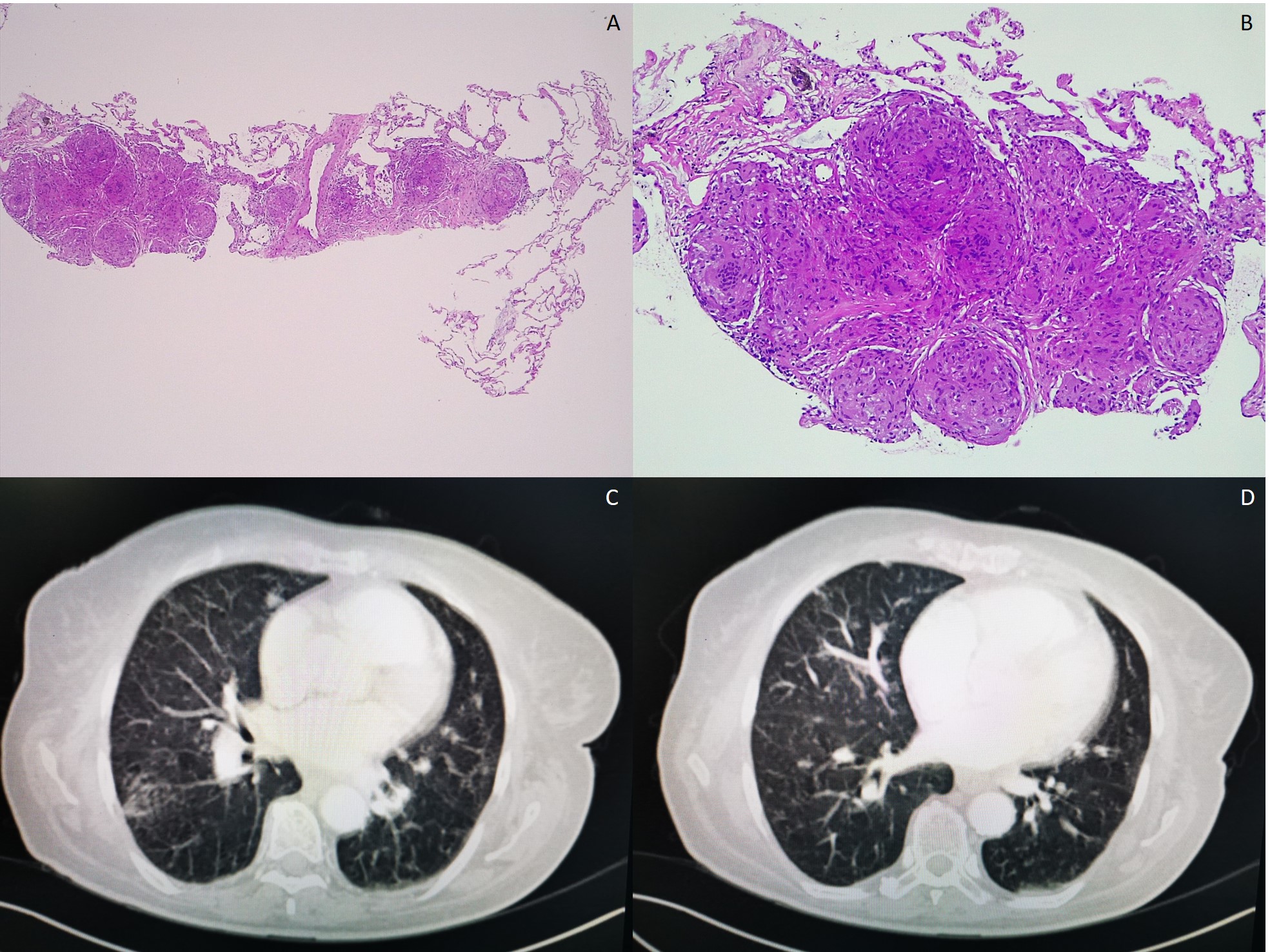

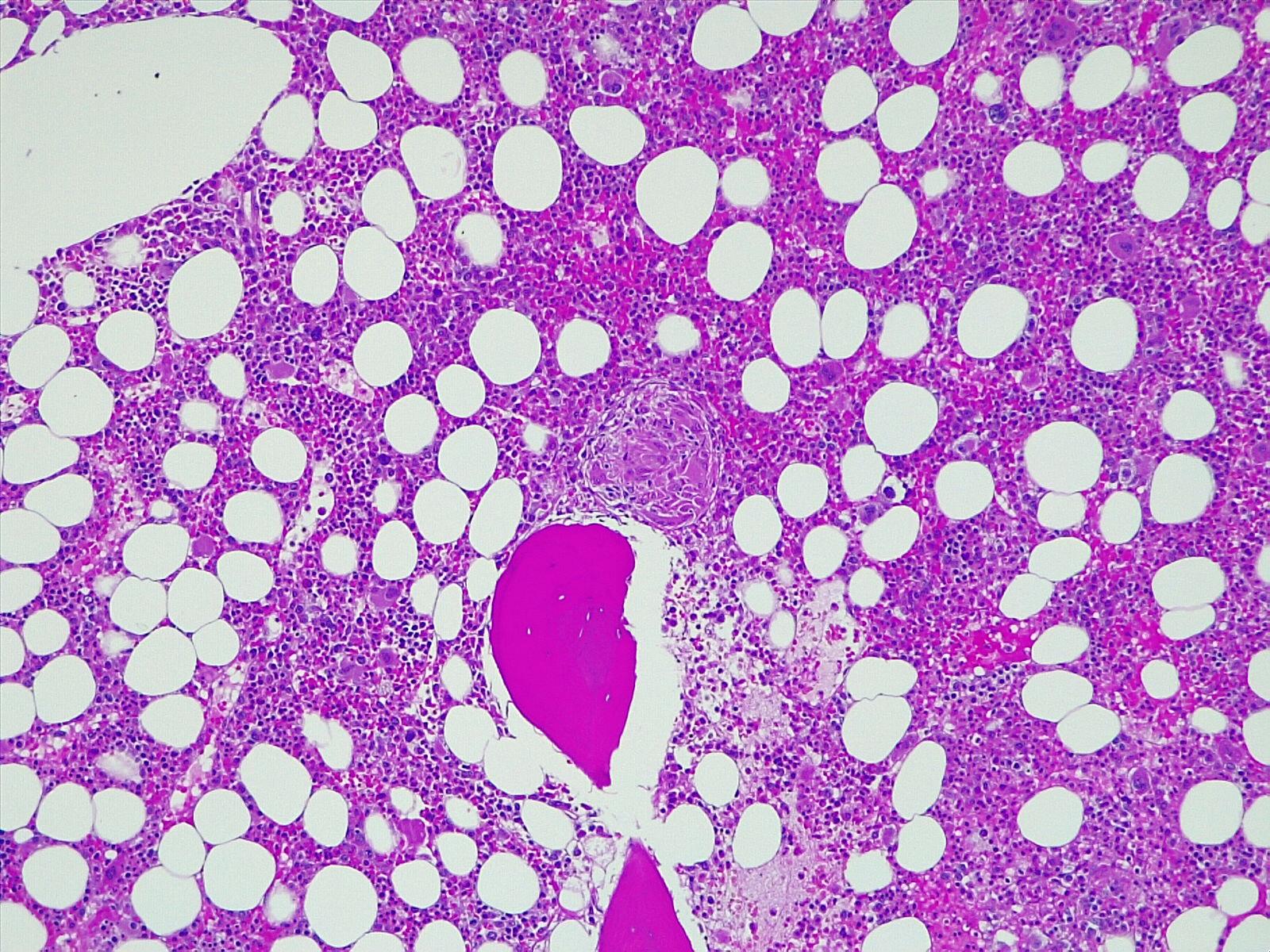

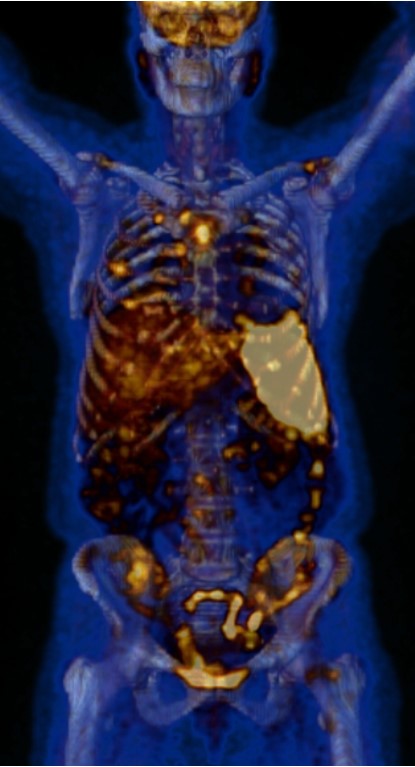

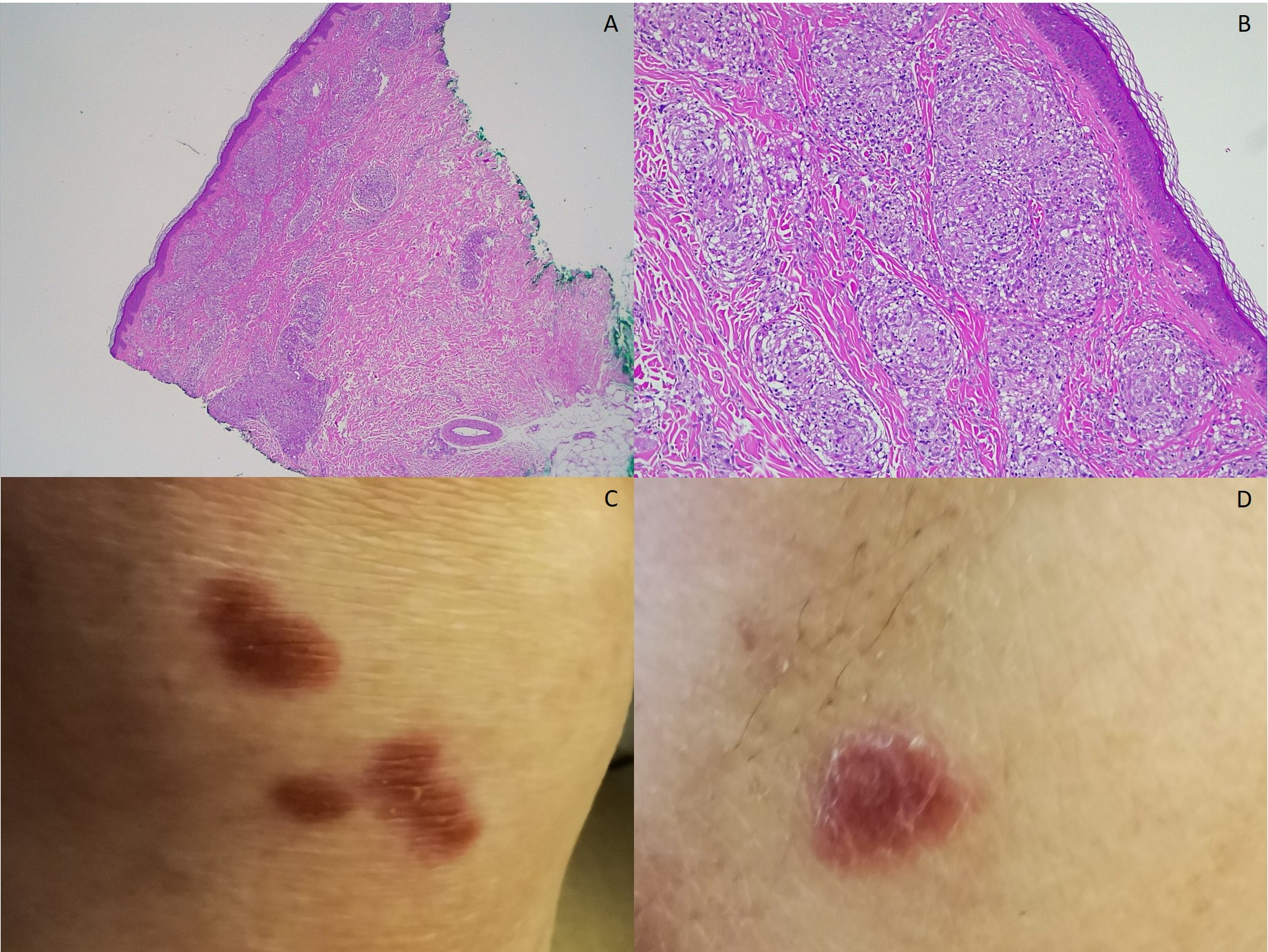

A renal ultrasound showed normal parenchyma and no signs of lithiasis. A thoracoabdominal-pelvic CT (Fig. 1) showed multiple small coalescent lymphadenopathies in mediastinum and hilar regions, multiple micronodules with a perilymphatic distribution associated with interlobular septae thickening; a slightly enlarged homogenous liver and spleen and multiple millimetric mesenteric and lombo-aortic lymphadenopathies. In this setting, lung biopsies were performed showing chronic non-caseating granulomatous inflammatory process with no signs of malignity (Fig. 1). Bone marrow aspirate and core biopsy also showed multiple non-caseating granulomas and was otherwise normocellular with trilineage haematopoiesis (Fig. 2). Fungal and acid-fast stains of both biopsies were negative. Angiotensin-converting enzyme was elevated (97U/L) and an extensive immunologic and infectious work-up was negative (Table 1). Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) revealed a metabolic active disease within the lungs (multiple bilateral parenchyma densification areas), mediastinum and hilar lymphadenopathies, spleen, bone marrow and possibly liver, suggesting an inflammatory/granulomatous disease (Fig. 3). Ophthalmic, cardiac, and neurologic sarcoidosis were excluded, by optical coherence tomography, FDG-PET/CT and cranial MRI, respectively. We also documented new onset violaceous skin plaques at the elbows and knees (Fig. 4) by the 10th day of hospitalization which were biopsied and showed non-caseating granulomas.

In the setting of multisystemic sarcoidosis methylprednisolone pulses were initiated (1g/day for 3 days) followed by prednisolone 1mg/kg/day. There was an excellent clinical and analytic response with normalization of calcium, haemoglobin, and renal function.

At follow-up, methotrexate was initiated as a corticoid-sparing agent due to corticoid tapering difficulties and related secondary effects (new-onset diabetes mellitus). Otherwise, our patient maintains a good clinical and analytical evolution.

DISCUSSION

Sarcoidosis typically presents with pulmonary manifestations and the most common diagnostic signs are bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (50% of cases) and diffuse micronodular pulmonary infiltration associated with a typical lymphatic distribution. In up to 50% of patients, it is detected incidentally by radiographic alterations.7 Respiratory symptoms include cough, dyspnoea, and chest discomfort. Radiographic changes can be classified in four stages: stage 1 is bilateral hilar adenopathy without infiltration, stage 2 is bilateral hilar adenopathy with infiltration as seen in our patient, stage 3 is infiltration alone and stage 4 is fibrosis.7,8

Pulmonary manifestations may be the most common presentation of sarcoidosis but 30% of patients can present with extrapulmonary manifestations involving the skin, eyes, lymph nodes, heart, kidney, and central nervous system.7 Lofgren’s syndrome, an acute presentation that consists of erythema nodosum, arthritis, and bilateral hilar adenopathy, occurs in 9-34% of patients and a probable diagnosis of sarcoidosis can be made without biopsy;9 in all other cases, a biopsy should be performed on the most accessible organ. Diagnostic criteria of sarcoidosis includes clinical and radiologic presentation, evidence of non-caseating granulomas, and no alternative diagnosis.8 Other initial assessments include pulmonary function tests, ophthalmologic evaluation, and blood tests including complete blood count, measurement of electrolytes and serum angiotensin-converting enzyme levels. Bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsy has a diagnostic yield of 85%, but FDG-PET scanning is the most valuable to detect occult disease.9

In our case, bone marrow biopsy displayed non-caseating epithelioid granulomas in bone marrow structure; malignant tumour, tuberculosis and fungal infections were excluded. Estimated incidence of granulomas in bone marrow biopsies is low (0.3–2.2%). In a published series based on 9641 bone marrow biopsies, 48 patients had granulomas and 21% of those were related to sarcoidosis.4,10Anaemia occurs in 13–28% of sarcoidosis patients and is associated with bone marrow granulomas in about 50% of cases, but its pathophysiology remains unclear.11 In our case, spleen could have also played a role in the pathophysiology of anaemia. Spleen involvement has an estimated prevalence of 10% and it is usually asymptomatic. Splenomegaly can occur and is rarely associated with pain or cytopenias.8

Hepatic involvement, suggested by FDG-PET results, is more frequent than splenic (20–30% of patients) and often also symptom-free; abnormal liver function tests are seen in about 20-30% of these patients.8

Approximately 30-50% of patients with this disorder have hypercalciuria, and 10-20% have hypercalcemia,2 but symptomatic hypercalcemia is rarely reported; we could not find reports of levels as elevated as in our patient. This calcium metabolism disorder occur due to activated macrophages expressing 1α-hydroxylase in sarcoid granulomas which leads to increased levels of 1.25-dihydroxy-vitamin D (calcitriol), resulting in increased intestinal absorption and renal excretion of calcium that can result in symptomatic hypercalcemia, nephrolithiasis, nephrocalcinosis, and acute and chronic kidney disease.12 Hypercalcemia normally suppresses PTH release and therefore calcitriol production, but in granulomatous diseases this isn’t seen because of the independent calcitriol production by activated macrophages which are resistant to the normal feedback control.2 Hypercalcemia decreases glomerular filtration rate by vasoconstriction of the afferent arteriole and inhibits sodium-potassium ATPase channels leading to urinary sodium wasting with polyuria and dehydration. Acute tubular necrosis can occur due to intracellular calcium overload and tubular obstruction with calcium precipitates. These consequences of hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria may become permanent.13 PTHrP, associated with malignancy hypercalcemia, may also contribute to hypercalcemia in some patients with sarcoidosis but not in our case.

Skin involvement is frequent (25-35% of patients) and is often overlooked because of lesions variability. Macules, papules and plaques commonly involve the neck, upper back, extremities, and trunk, and may also appear in scars and tattoos.

There is no cure for sarcoidosis, but treatment changes the granulomatous process and its clinical consequences. Remission occurs for more than 50% of patients within 3 years of diagnosis. Unfortunately, up to 30% of patients have persistent disease with significant organ impairment.9 Major indications for treatment are cardiac, neurological, or kidney involvement, ocular sarcoidosis refractory to topical therapy, and symptomatic hypercalcaemia.8

As there was severe symptomatic hypercalcemia, treatment was mandatory in this patient. When there is symptomatic hypercalcemia, we must start intravenous fluids and corticosteroids immediately; bisphosphonates can be added. A rapid reduction is expected in serum calcium, but in some cases, sarcoidosis‐induced hypercalcaemia may be resistant to this approach, and a loop diuretic or calcitonin may need to be administered.15 Systemic corticosteroids remain the standard treatment for sarcoidosis.8Usually, it is required about 9 months of treatment and experts recommend a dosing schedule of daily 30-40mg of prednisone with a biweekly taper of 5mg until 10-20mg is reached. Several alternatives can be considered for those who do not tolerate corticosteroids.9,14 Adalimumab can be used when corticosteroids are contraindicated in cases of severe bone marrow sarcoidosis.4Conventional corticosteroid-sparing drugs are antimalarial drugs, methotrexate, or azathioprine. Methotrexate is more commonly used for corticosteroid-resistant disease.8

CONCLUSION

Sarcoidosis diagnosis is usually a challenge and may be delayed because of its nonspecific and unusual presentations. Bone marrow involvement should be considered in sarcoidosis patients with cytopenia. Hypercalcemia is rarely a presenting manifestation, with clinically significant hypercalcemia occurring in less than 5% of patients. FDG-PET allows the diagnosis of occult disease and bone marrow involvement.

Quadro I

Blood tests

| Hb (g/dL) | 10,9 | K+ (mmol/L) | 4,5 | Serum iron (µg/dL) | 41 | 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D (pg/mL) | 75,0 | dsDNA | Negative |

| VGM (fL) | 80,4 | Cl- (mmol/L) | 97 | Transferrin (mg/dL) | 237 | 24h Urinary calcium (mg/day) | 380 | ACE (U/L) | 97 |

| HGM (pg) | 25,9 | Ca2+ (mg/dL), corrected | 16,92 | Total iron binding capacity (µg/dL) | 333 | Coombs test | Negative | CMV | IgG+IgM- |

| Leukocytes (/μL) | 4000 | P (mg/dl) | 4,6 | Ferritin (ng/mL) | 58,23 | β2-microglobulin (µg/L) | 11200 | EBV EBNA | IgG+ |

| Neutrophiles (/μL) | 3200 | Mg2+ (mg/dL) | 1,9 | B12 vitamin (pg/mL) | 182 | IgG (mg/dl) | 1348 | EBV VCA | IgG+IgM- |

| Lymphocytes (/μL) | 600 | AST (U/L) | 25 | Folate (ng/ml) | 8,1 | IgA (mg/dl) | 501 | HBV HBsAg and HBsAb | Negatives |

| Platelets (/μL) | 167000 | ALT (U/L) | 21 | Albumin (g/dL) | 3,7 | IgM (mg/dl) | 48 | HCV Ab | Negative |

| PT (s) | 12,7 | Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 121 | TSH (µU/mL) | 0,51 | Kappa light chains (mg/dl) | 344,9 | HIV 1 and 2 | Negatives |

| INR | 1,07 | γ-GT (U/L) | 56 | FT4 (ng/dl) | 1,04 | Lambda light chains (mg/dl) | 201,9 | IGRA | Negative |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 141 | LDH (U/L) | 155 | PTH (pg/mL) | 4,0 | Urine immunofixation | Negative | Galactomannan test | Negative |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 3,4 | ESR (mm/h) | 56 | PTHrp (pmol/L) | 0,3 | Bence Jones protein | Negative | Brucella Ab | IgG-IgM- |

| Na+ (mmol/l) | 138 | CRP (mg/dL) | 0,41 | 25-hydroxyvitamin D (ng/mL) | 10,7 | Antinuclear Ab | Negative | Bacteria and mycobacterian blood cultures | Negatives |

Figura I

A and B: lung biopsy H&E 40x and 100x, respectively – lung with conserved structure, with focal areas of alveolar septae enlargement, due to sarcoid non-caseating granulomas; C and D: thoracic CT showing multiple small coalescent lymphadenopathies in mediastinum and hilar regions, as well as multiple micronodules with a perilymphatic distribution associated with interlobular septae thickening.

Figura II

Bone core biopsy showing multiple focal sarcoid non-caseating granulomas and otherwise normocellular with trilineage haematopoiesis

Figura III

FDG-PET/CT showing metabolic active disease within the lungs (multiple bilateral parenchyma densification areas), mediastinum and hilar lymphadenopathies, spleen, bone marrow and possibly liver, suggesting an inflammatory/granulomatous disease.

Figura IV

A and B: skin biopsy from knee lesions observed in C, H&E 40x and 100x, respectively – granulomatous infiltrate in papillary and reticular dermis, epidermis with no alterations; C: right knee; D: left elbow.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Bargagli, E., & Prasse, A. (Apr de 2018).Sarcoidosis: a review for the internist. Intrern Emerg Med, 13(3), 325-31.

2. Maalouf, N. (24 de Jun de 2019).Hypercalcemia in granulomatous diseases. Obtido de UpToDate: https://www.uptodate.com/

3. Sugai, M., Murata, O., Oikawa, H., Katagiri, H., Matsumoto, A., Nagashima, H., . . . Maemondo, M. (Aug de 2020). A case of bone marrow involvement in sarcoidosis with crescentic glomerular lesions. Respir Med Case Rep.

4. Peña-Garcia, J. I., Shaikh, S., Barakoti, B., Papageorgiou, C., & Lacasse, A. (Apr de 2019).Bone marrow involvement in sarcoidosis: an elusive extrapulmonary manifestation. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect, 9(2), 150-4.

5. Frieder, J., Kivelevitch, D., & Menter, A. (Apr de 2018). Symptomatic hypercalcemia and scarring alopecia as presenting features of sarcoidosis. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent), 31(2), 224-6.

6. Hameed, O. A., & Skibinska, M. (2011). Scar sarcoidosis with bone marrow involvement and associated musculoskeletal symptoms. BMJ Case Rep.

7. Sharma, N., Tariq, H., Uday, K., Skaradinskiy, Y., Niazi, M., & Chilimuri, S. (Jun de 2015). Hypercalcemia, Anemia, and Acute Kidney Injury: A Rare Presentation of Sarcoidosis. Hindawi Case Reports in Medicine.

8. Valeyre, D., Prasse, A., Nunes, H., Uzunhan, Y., Brillet, P.-Y., & Müller-Quernheim, J. (Mar de 2014). Sarcoidosis. Lancet, 383(9923), 1155-67.

9. Iannuzzi, M. C., & Fontana, J. R. (Jan de 2011). Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis, and therapeutics. JAMA, 305(4), 391-9.

10. Hugo, L. B., Ffrench, M., Broussolle, C., & Sève, P. (Jul de 2013). Granulomatous lesions in bone marrow: clinicopathologic findings and significance in a study of 48 cases. Eur J Intern Med, 24(5), 468-73.

11. Prost, N. d., Kerrou, K., Sibony, M., Talbot, J.-N., Wislez, M., & Cadranel, J. (2010). Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose with positron emission tomography revealed bone marrow involvement in sarcoidosis patients with anaemia. Respiration, 79(1), 25-31.

12. Judson, M. A. (Aug de 2015). The Clinical Features of Sarcoidosis: A Comprehensive Review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol, 49(1), 63-78.

13. Correia, F. A., Marchini, G. S., Torricelli, F. C., Danilovic, A., Vicentini, F. C., Srougi, M., . . .Mazzucchi, E. (Jan-Feb de 2020). Renal manifestations of sarcoidosis: from accurate diagnosis to specific treatment. Int Braz J Urol, 46(1), 15-25.

14. Iannuzzi, M. C., Rybicki, B. A., & Teirstein, A. S. (Nov de 2007).Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med, 357(21), 2153-65.

15. Eklund, A., & Bois, R. M. (Apr de 2014).Approaches to the treatment of some of the troublesome manifestations of sarcoidosis. J Intern Med, 274(4), 335-49.