Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 can be responsible for a wide variety of symptoms, most of them involving the respiratory tract. Although the most widely known presentation may be as pneumonia, viral-induced laryngeal inflammation may also be very severe and associated with life threatening complications.

Case Description

We describe the case of a 59-year-old male patient admitted due to stridora month after being treated for SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. His previous medical history was only remarkable for type 2 diabetes mellitus, without known micro or macrovascular complications, with a good metabolic control; high blood pressure; dyslipidemia and regular alcohol consumption.

The patient was in his usual state of health until two weeks before he was admitted for the first time, when he started a dry cough and dysgeusia. At the emergency department (ED) he complained of progressively worsening shortness of breath on exertion. He denied fever, headache or myalgia. He denied previous similar episodes. He had not travelled recently nor did he have contact with anyone known to have COVID-19. The patient was tachycardic (heart rate 100bpm) with elevated blood pressure 166/91mmHg and feverish (tympanic temperature of 38.3 ºC). He was polypneic at rest, with a peripheral oxygen saturation of 92%. He presented crackles on the left lower pulmonary base and a chest x-ray with a bilateral patchy shadowing. No other imaging tests were used. He had a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test result for COVID-19.

The patient was then transferred to the infectious diseases ward where there was a progressive worsening of the respiratory failure during the first three days after admission. He was then transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) due to the need for mechanical ventilation. On that day he started therapy with remdesivir (10 days) and methylprednisolone 40mg every 12 hours for 5 days. No antibiotic therapy was started.

During his stay at the ICU, he presented a favorable evolution, requiring mechanical ventilation only for the first 5 days. He did not need to do any prone position periods and cuff leak test was negative. After extubation he did not need noninvasive ventilation. He started low-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy and was transferred to the internal medicine ward and discharged 10 days after he was extubated (apparently without any complications). At discharge the patient was considered cured of the SARS-CoV-2 infection but maintained complaints of severe dry cough and odynophagia. Later at home, he referred hoarseness that he associated with the persistence of the cough. Twenty eight days after hospital discharge, and with persistent frequent and severe cough he developed dyspnea with a feeling of upper airway obstruction that progressively worsened, and the patient was readmitted to the ED due to dyspnea and stridor. Upon arrival at the ED, the patient was alert, oriented, hypertensive. Nasofibrolaryngoscopy was performed showing marked supraglottic edema and bilateral severe hypomobility of the vocal cords. Due to worsening of the clinical state, orotracheal intubation was performed. Cervico-thoracic CT was performed, showing diffuse edematous infiltration of the larynx, with diffuse edema of the visceral space of the neck, globosity of the parotids and submandibular glands; predominantly peripheral bilateral ground-glass pulmonary opacities with diffuse distribution and small peripheral subpleural areas of consolidating pulmonary parenchyma, predominantly in the lower lobes (Fig. 1 and 2).

Surgical tracheotomy was performed under general anesthesia and therapy with methylprednisolone 1mg/Kg/day was initiated. PCR for SARS-CoV-2 was negative. His laboratory workout was unremarkable, apart from a high erythrocyte sedimentation ratio of 76mm/hr.

To exclude a central cause for the vocal cord paresis, he also underwent brain CT and brain MRI, which were unremarkable. He also performed an electromyography of the lower and upper limbs, to exclude any Guillain Barré syndrome, revealing only a mild myopathy associated with prolonged hospitalization. He completed 5 days of methylprednisolone 1mg/kg/day and subsequently started prednisolone 1mg/kg/day, having been discharged on a corticosteroid tapering regimen.

During hospitalization, two nasofibrolaryngoscopies were performed, the first after the end of 5 days of methylprednisolone, showing bilateral edema of the arytenoid folds, mainly on the right; paralysis of the right hemilarynx and hypomobility of the left hemilarynx, with reduced glottal cleft and the second on the 16th day of hospitalization, already under prednisolone 15mg/day (tapering scheme), without edema of the arytenoid and good mobility of the vocal cords. Before discharge, the tracheotomy was closed without complications.

Discussion

SARS-CoV-2 virus has the potential to cause airway edema and laryngitis which frequently complicate the airway management in these patients.1 Although it has not yet been described in SARS-CoV-2, many of the other members of the coronavirus family have been associated with the development of laryngitis, 2 which could help explain why these patients seem to have a higher risk of post-extubation stridor. Post-viral cough can persist for over two months after SARS-CoV-2 infection,3 enhancing the laryngeal inflammation.

Laryngeal edema is reported in up to 55% of all critically ill patients following tracheal extubation.4 It can appear as early as 24h after, and the incidence increases with the duration of tracheal intubation.5

In the case we report there were no problems described with the intubation or with the extubation processes the first time around and stridor only began 28 days after the extubation. We would also like to highlight that the patient was under mechanical ventilation for a short period of time (5 days). We believe that the inflammation of the larynx was enhanced by the persistent cough and that it affected the vibration of the vocal folds adversely, causing a severe bilateral hypomobility of the vocal cords.

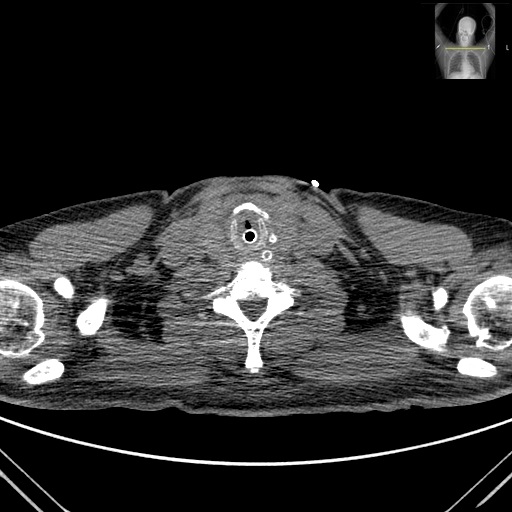

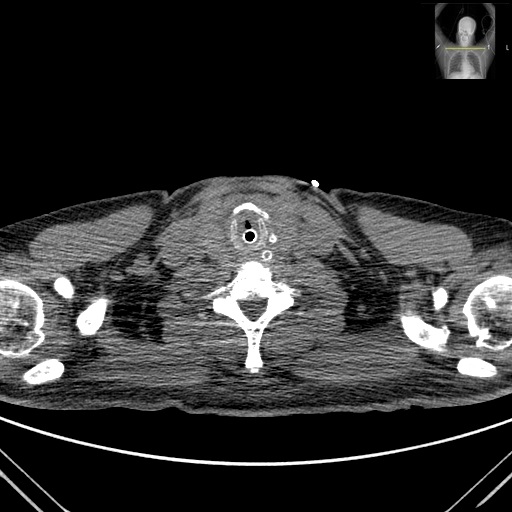

Figura I

Neck CT scan axial section showing a diffuse edematous infiltration of the larynx

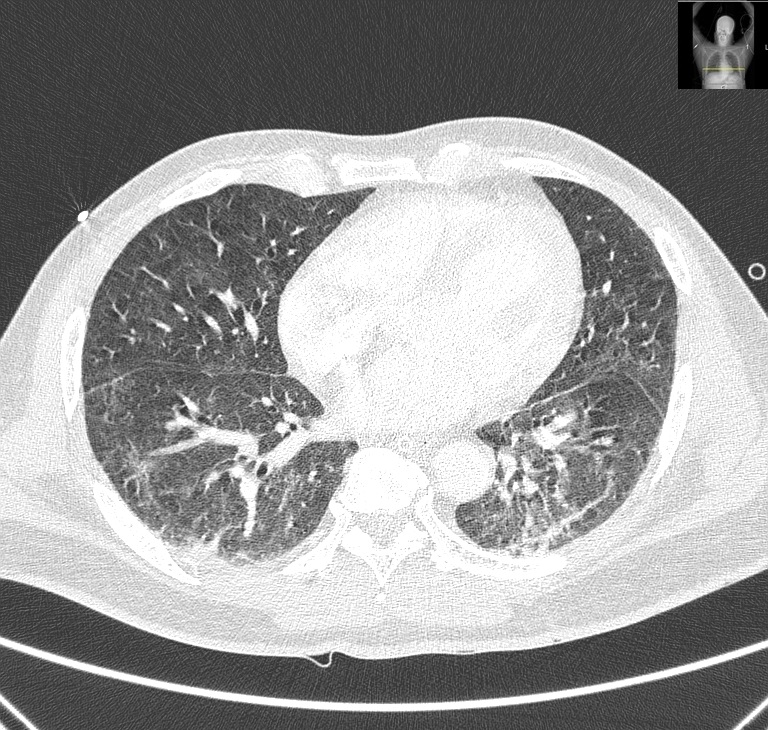

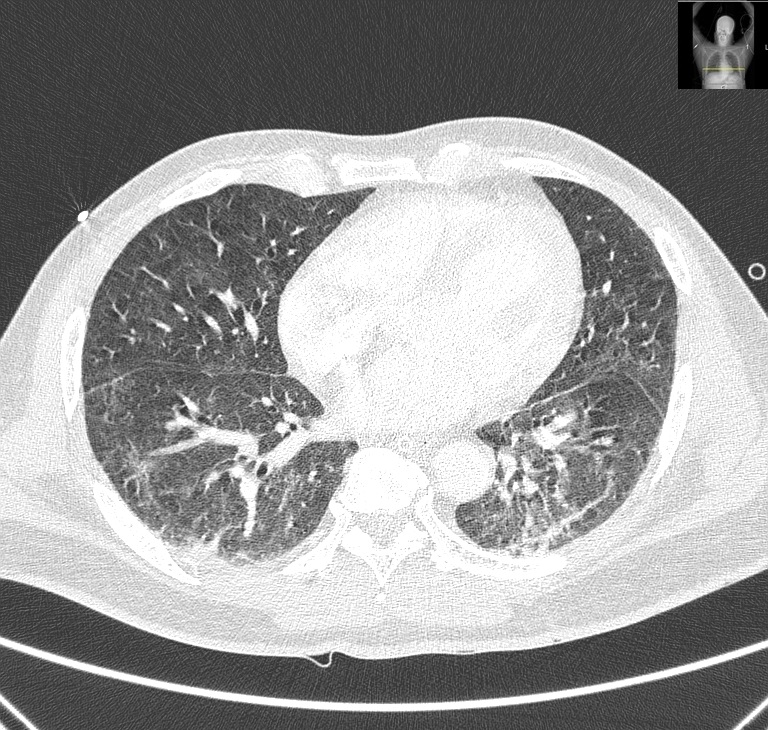

Figura II

Chest CT scan axial section showing peripheral bilateral ground-glass pulmonary opacities

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1 – McGrath, B A; Wallace, S; Goswamy, J. Laryngeal oedema associated with COVID-19 complicating airway management. Anaesthesia; 75(7): 972, 2020 07.

2 - Vabret A, Mourez T, Gouarin S, Petitjean J, Freymuth F. An outbreak of coronavirus OC43 respiratory infection in Normandy, France. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:985–989.

3 – Carfì A.,Bernabei R.,Landi F, et al. Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(6):603-605.

4 – Zhou T, Zhang HP, Chen WW, et al. Cuff-leak test for predicting postextubation airway complications: a systematic review. Journal of Evidence Based Medicine 2011; 4: 242–54.

5 – Lake M. What we know so far: COVID-19 current clinical knowledge and research. Clinical Medicine 2020; 20: 124–7.