LEARNING POINTS- Patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection have increased risk of arterial and venous thrombosis.

- Thrombosis is an important factor of bad prognosis in these patients.

- Preliminary reports of randomised control trials show no benefit for prophylactic therapeutic anticoagulation in severe cases.

BACKGROUNDInfection by SARS-CoV-2 presents itself as a mild to severe pneumonia, often associated with severe respiratory failure. This infection is associated with an higher risk of both arterial and venous thromboembolism, particularly in severe disease.

Prophylactic anticoagulation in higher doses has been recommended for patients in critical care, although recent trials prove no benefit. There are no recommendations for those with mild disease.

CASE DESCRIPTIONA 58 years old woman, without any medical history despite obesity, was admitted to the emergency department (ER) with decreased consciousness and difficulty breathing. She had been diagnosed with SARS-COV-2 infection 10 days earlier, presenting only mild symptoms as myalgia and asthenia, requiring no hospitalization or care. She was last known well about 8 hours prior.

On physical examination, she was found to have a Glasgow coma scale of 6/15 (no verbal or eye opening response, and abnormal flexion to pain).

She was hemodynamically unstable (arterial blood pressure of 65/35 mmHg, heart rate 134 rpm), and it was not possible to measure oxygen saturation.The patient was quickly intubated endotracheally, both to protect the airway and to improve ventilation, with a slight improvement in hypoxemia (pO2 66 mmHg with FiO2 100%).

She presented an episode of wide QRS complex tachycardia, and was successfully submitted to electric cardioversion with single 150 joules synchronized shock, returning to sinus tachycardia. Aminergic support was started with noradrenaline, requiring increasingly higher doses.

Arterial blood gases showed severe type 2 respiratory insufficiency with respiratory acidosis (pH 7.10 pCO2 77 mmHg pO2 27 mmHg HCO3 23 mEq/L Lac 1.6 mmol/L).

Brain computerized tomography (CT) scan revealed an occlusion of M1 segment of the right medial cerebral artery, associated with an extensive hypodensity on the right hemisphere (involving cortico-subcortical fronto-temporo-parietal, insular and lenticular sections), with cortical sulcal effacement and mass effect on the right ventriculus, thus showing recent ischemic lesion of the entire territory of this artery.

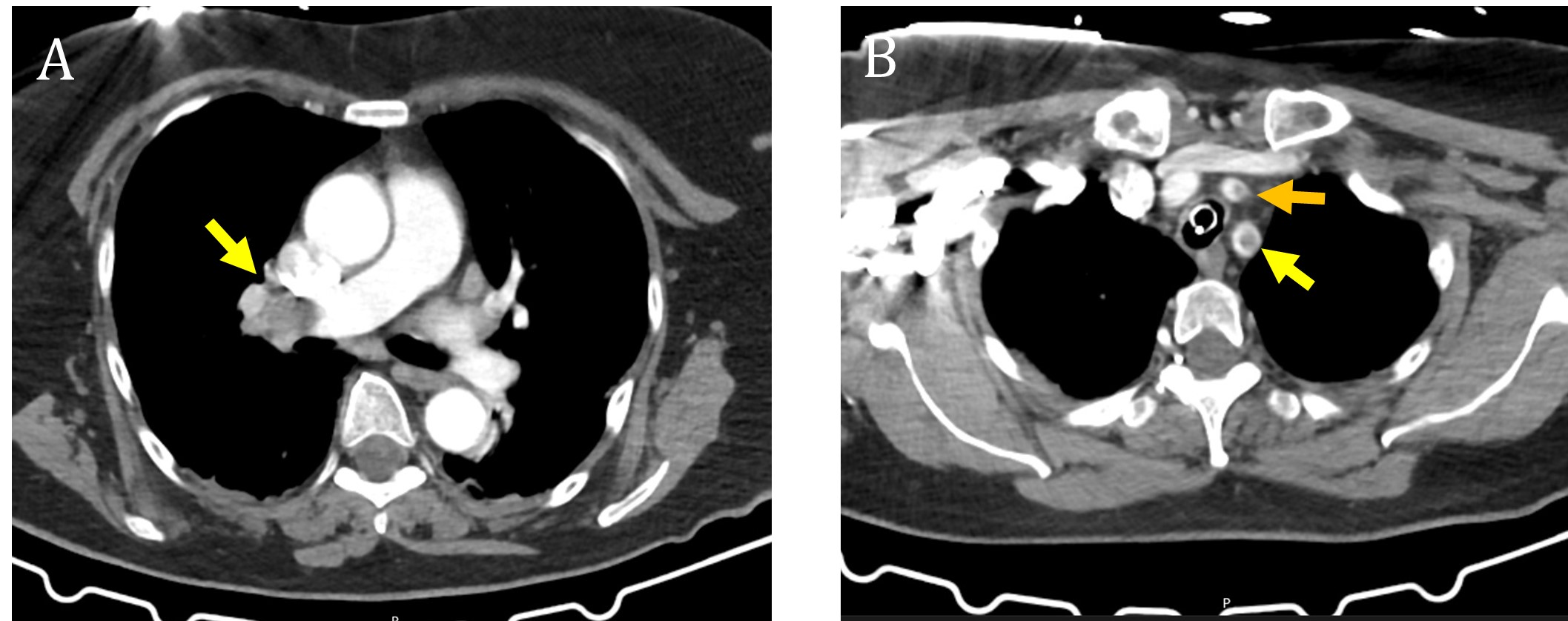

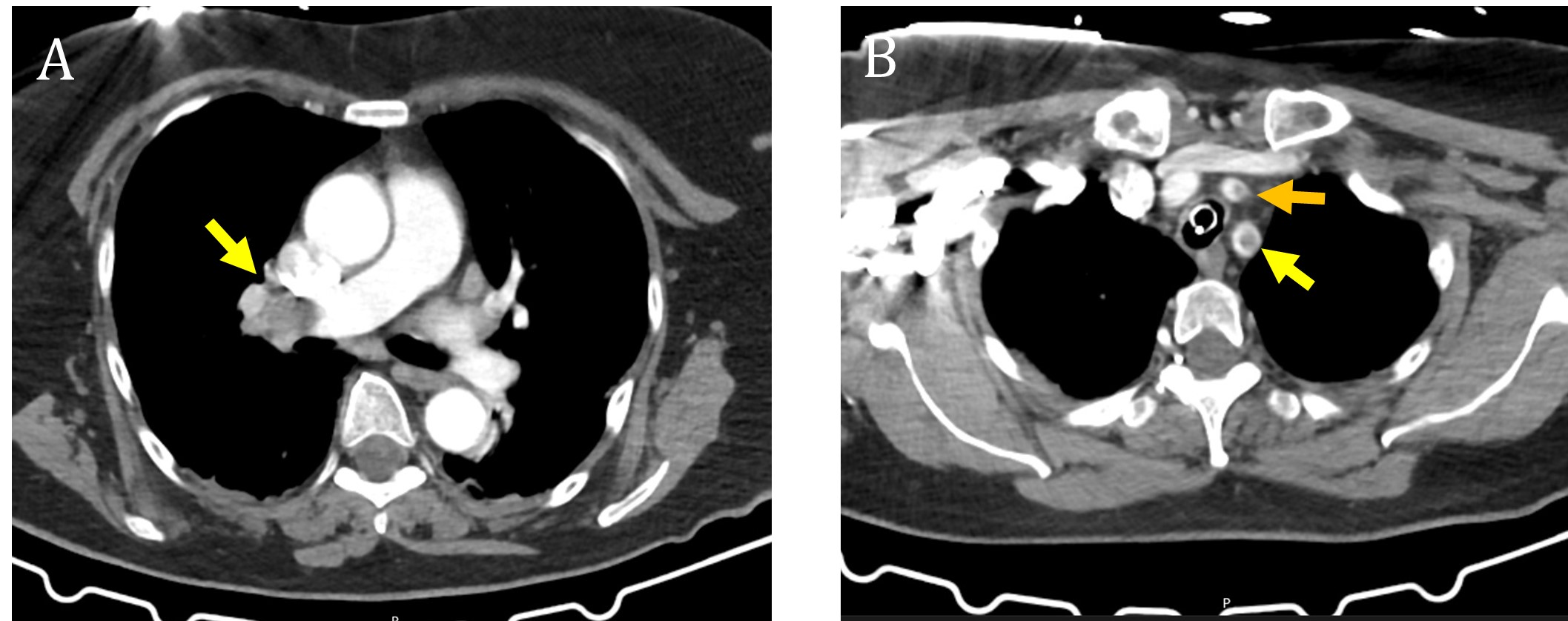

Pulmonary CT documented discreet peripheral ground glass opacities in both lungs compatible with viral pneumonia. CT pulmonary angiography revealed pulmonary emboli involving the right main pulmonary artery, right lung lobar arteries, and bilateral segmental arteries (Figure 1). Emboli were also found on both common carotid arteries, and on the left subclavian artery. Radiological signs for right heart strain were identified – dilation of right cardiac chambers and flattening of the interventricular septum.

Intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) was withheld, as the patient was outside of the tPA window and presented with multi-lobal stroke. Since the patient had a severe hemispheric stroke, with established ischemic lesions, it was decided she was not a candidate for pulmonary thrombectomy.The patient quickly developed severe respiratory failure with concomitant obstructive shock, despite ventilatory and haemodynamic support, and died less than two hours after being admitted to the ER.

DISCUSSIONIn this case, we reported a patient with extensive thromboembolic events in the cerebral arterial system and pulmonary vasculature, in the course of an infection by SARS-CoV-2, in absence of known risk factors such as surgery, immobilization or hormonotherapy. Due to its catastrophic nature, it was not possible to exclude any thrombophilia, such as mutations of factor V Leiden or prothrombin.

SARS-CoV-2 predisposes patients to thromboembolic disease, and significantly contribute to mortality and morbidity. Several mechanisms have been suggested, including thrombosis triggered by macrophage activation syndrome, cytokine storm, the complement cascade, and RAS dysregulation.

1The incidence of venous and arterial thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, requiring hospitalization, has been well established in several case series.

2 However, thromboembolic complications can be present in patients with mild symptoms, and on occasion, even prior to respiratory symptoms. Larger cohorts of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection need to be evaluated to assess the risk of acute thromboembolic disease, of all types, as an independent risk factor.

Many experts are recommending high-dose thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized patients, and several hospitals are already abiding by it. However, there has been no recommendations for patients with mild disease.

3 Multiple trials are underway to test prophylactic measures in hospitalized patients. The REMAP-CAP, ACTIV-4a, ATTACC trial’s preliminary reports shows no benefit in hospital survival, in patients with therapeutic anticoagulation: this trial included 1074 patients (529 with therapeutic anticoagulation and 545 with usual care pharmacological thromboprophylaxis) and they had similar hospital survival (64.3% vs. 65.3%, adjusted odds ratio 0.88). Although this trial showed that patients with therapeutic anticoagulation presented lower levels of major thrombotic events (5.7% vs. 10.3%), major bleeding was, as expected, higher on this group (3.1% vs 2.4%).

4The INSPIRATION trial included 600 patients, and it showed that intermediate-dose compared with standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, did not result in a significant difference in the primary outcome of a composite of adjudicated venous or arterial thrombosis, treatment with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or mortality within 30 days.

5This case supports the growing evidence that hypercoagulability is a significant factor in COVID-19-related complications and prognosis, even in mild disease, showing the importance of heightened vigilance for thromboembolic complications, allowing for an expedited diagnosis and efficient treatment.

Nevertheless, this case had a fulminant, catastrophic development, rending therapeutic options futile. We argue that there is a pressing need for clinical trials assessing different prophylactic measures, not just therapeutic anticoagulation, to prevent such cases. These measures may include antiviral therapies, immunomodulators and agents capable of stabilising endothelial dysfunction, such as a statins and ACE inhibitors. Clinical suspicion with early diagnosis is extremely important, but prevention strategies can become a game changer.

Figura I

CT pulmonary angiography: Panel A shows pulmonary thromboembolism (yellow arrow), Panel B shows emboli on left common carotid and left subclavian arteries (orange and yellow arrow, respectively).

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Hanff TC, Mohareb AM, Giri J, Cohen JB, Chirinos JA. Thrombosis in COVID-19. Am J Hematol. 2020 Dec;95(12):1578-1589. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25982

2. Tan BK, Mainbourg S, Friggeri A, et al. Arterial and venous thromboembolism in COVID-19: a study-level meta-analysis Thorax Published Online First: 23 February 2021. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215383

3. The British Thoracic Society. Bts guidance on venous thromboembolic disease in patients with COVID-19, 2020. Available: https://brit-thoracic.org.uk/about-us/covid-19-information-for-the-respiratory-community/

4. The REMAP-CAP, ACTIV-4a, ATTACC Investigators, Ryan Zarychanski. Therapeutic Anticoagulation in Critically Ill Patients with Covid-19 – Preliminary Report medRxiv2021.03.10. 21252749; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.10.21252749

5. INSPIRATION Investigators. Effect of Intermediate-Dose vs Standard-Dose Prophylactic Anticoagulation on Thrombotic Events, Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Treatment, or Mortality Among Patients With COVID-19 Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: The INSPIRATION Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. Published online March 18, 2021. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.4152