Introduction

Right heart infective endocarditis (RHIE) is a rare condition, accounting for 5-10% of all infective endocarditis (IE).1 Tricuspid valve endocarditis represents most of the cases among RHIE, being pulmonary valve (PV) endocarditis responsible for only 1-2%.2 The major risk factors for RHIE include IV drug abuse, immunosuppression (including HIV-patients1), previous device implantation (pacemaker/ICD), having central venous catheter and congenital cardiac disease.2 Staphylococcus aureus is the main agent (60-90% of cases), although polymicrobial infections have been increasing.1 In-hospital mortality of RHIE is approximately 7%,1 while it is 15-30% in left endocarditis.3

Case Report

We present the case of a 72-year-old caucasian male, with previous history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, aortic prosthetic mechanical valve (replaced due to symptomatic aortic stenosis 4 years before) and hip replacement surgery 3 months before. He had no history of toxics abuse.

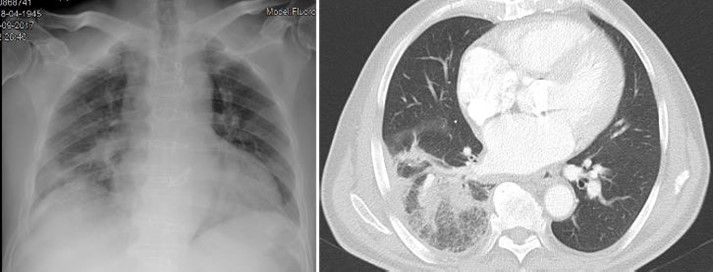

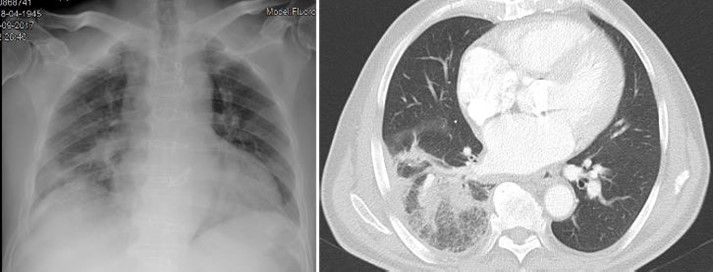

He was admitted in the emergency room (ER) complaining of a 3-day lasting right inferior thoracic pain, fever and dry cough. He also had a 10% weight loss in the previous three months. At admission he had normal vital signs: BP 123/62mmHg; HR 68bpm; Temperature 37.2ºC; SpO2 98% (FiO2 21%). The physical exam was irrelevant except for the evidence of crackles on the right hemithorax. Blood tests revealed normocytic normochromic anaemia (Haemoglobin 9.3g/dL, VGM 80fL, CHGM 30mg/dL) and elevated inflammatory parameters (leucocyte count 14720/uL, Neutrophil count 89.4%, C-reactive protein (CRP) 30mg/dL (<0.50), ESR 27mm/h (<20mm/h), being the remaining exams (including liver and renal tests) unremarkable. Screening for HIV, hepatitis B and C were negative. The X-ray showed an opacity on the right lung (Fig. 1) and he was diagnosed with a right upper pneumonia. Blood cultures were collected and he started empiric antibiotic therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and azythromicin. For a better lung characterization, he was submitted to a thoracic CT that was in keeping with an extensive right pneumonia (Fig. 1).

During the hospitalization, and because there was a poor response to amoxicillin/ clavulanic acid and azythromicin, we switched antibiotic therapy to ceftriaxone. There was a Streptococcus gallolyticus isolated after, in two blood cultures.

Given the unusual microorganism isolated and the consumptive complaints leading to anaemia, he was submitted to an endoscopic study. The upper gastrointestinal exam revealed a chronic gastritis and the colonoscopy showed a colonic polyp <5mm.

Considering that the patient had a prosthetic aortic valve and bacteraemia, a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) was performed during hospitalization, revealing a normal functioning aortic mechanical valve, with no other relevant findings.

In view of the exuberant pneumonia and to rule out lung cancer or other complication, he underwent bronchofibroscopy, which was normal.

He completed 14 days of ceftriaxone and was discharged asymptomatic, with negative control blood cultures and negative inflammatory parameters.

One month later, he returned to the ER, presenting with fever (38ºC) and dry cough again. The physical examination was normal except for crackles on the right lung. Cardiac auscultation didn’t have murmurs. Blood tests revealed normal leucocyte count 9620/uL, but elevated CRP (12.5 mg/dL (<0.50)), being the remaining exams normal. The X-ray showed an opacity on the right upper and middle lobes. The blood cultures were again positive for Streptococcus gallolyticus (penicillin MIC: 0.047mg/L).

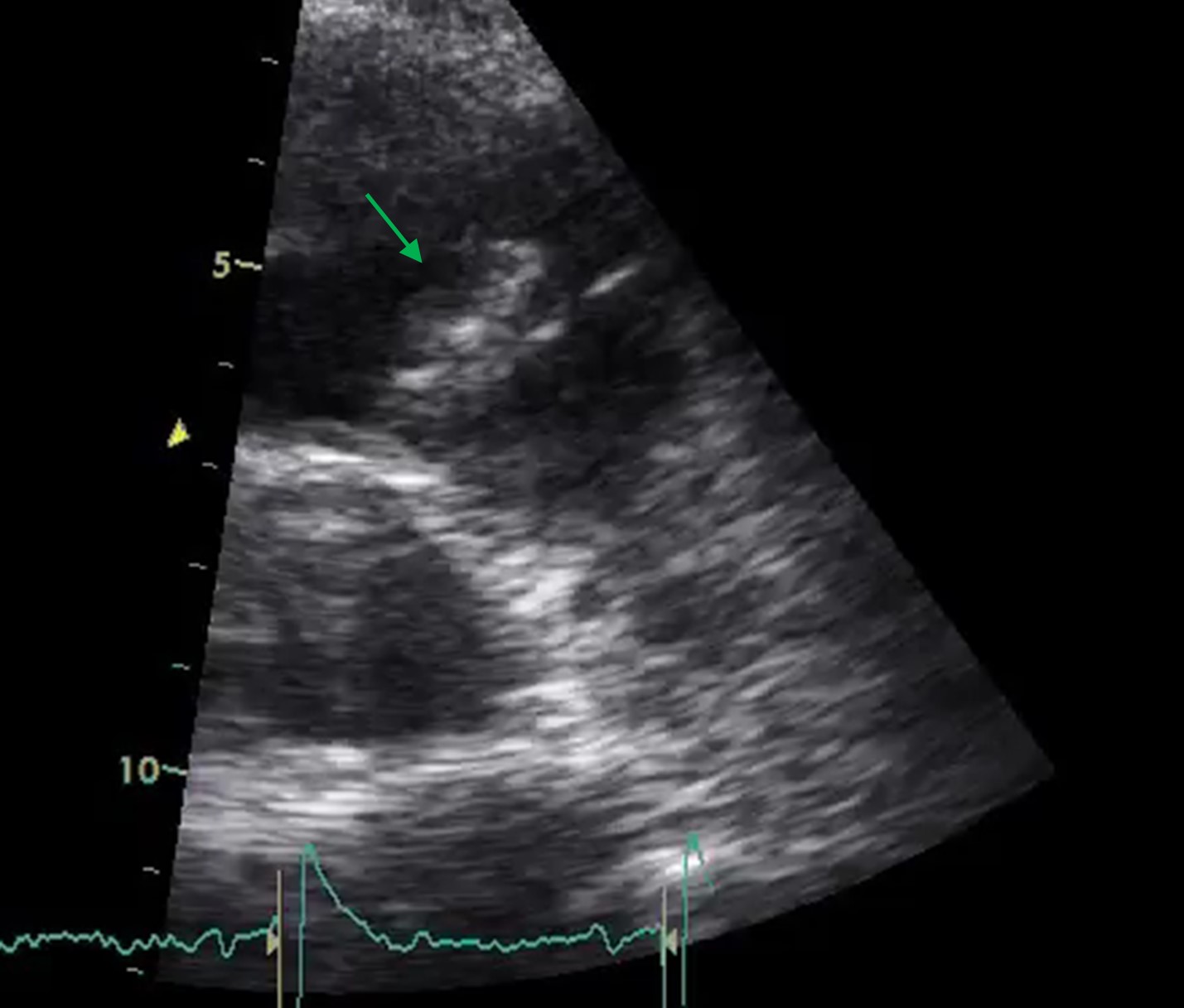

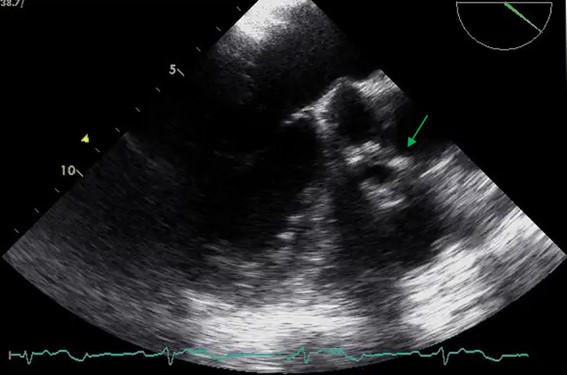

At this point, considering the recurrent pneumonia, as well as the isolated agent (not typical for pneumonia), we highly suspected of infectious endocarditis. He started benzathine penicillin and was submitted to a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) that showed a pulmonary valve vegetation (18x11mm), with a normal aortic prosthetic valve (Fig. 2). The case was discussed in a multidisciplinary team with Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery and the patient was proposed to conservative treatment. We added 2 weeks of gentamicin to the treatment.

During the time he was admitted to the hospital, there were not right heart failure signs. Vital signs remained normal and there was an improvement in his blood inflammatory parameters (leucocyte count 5150/uL, CRP 0.6mg/dL (<0.50), although worsening renal function (creatinine 1.20mg/dL). He completed 6 weeks of benzathine penicillin and 2 weeks of gentamicin. There was clinical and analytics improvement and he repeated a TTE at the third week of treatment showing a pulmonic valve vegetation with similar dimensions (18x7mm). The heart team considered the hypothesis of conservative approach as the best option taking into account surgery risk/benefit, due to the absence of significant valve dysfunction. He was considered cured after the 6 weeks of treatment and discharged asymptomatic, with negative blood cultures.

Three months later he returned with the same complaints. The TTE showed a bigger vegetation (22x12mm), leading to moderate pulmonary valve insufficiency. The case was further discussed in heart team. He was treated with 3 weeks of benzathine penicillin and 2 weeks of gentamicin, at the end of which he was submitted to a successful pulmonic valve replacement surgery.

The post-surgical valve culture isolated a Staphylococcus epidermidis vancomycin-sensitive, for whom the patient completed 6 weeks of additional directed-antibiotic. During this period, he went through physical and respiratory rehabilitation, with slight improvement in his tiredness but no signs of right or left heart failure. He repeated TTE, showing a normal functioning pulmonary prosthetic valve. At discharge, he was asymptomatic, had normal vital signs and analysis (leucocyte count 4540/uL, CRP 0.4mg/dL and creatinine 1.29mg/dL).

Discussion

Right-heart infective endocarditis (RHIE) is a rare entity. Lower pressure gradients as well as reduced oxygen content in the venous blood are some of the mechanisms proposed to the lower incidence of RHIE.4

RHIE diagnosis implies a high clinical suspicion. The clinical presentation includes persistent fever, bacteraemia and multiple septic pulmonary emboli, which may manifest as chest pain, cough or haemoptysis.1The “tricuspid syndrome” (repeated respiratory events, anaemia and microscopic haematuria) must alert the clinician to the RHIE.5 TTE is usually sufficient to detect tricuspid endocarditis but TEE is more sensitive and usually necessary in the detection of pulmonary valve vegetations and associated left-sided involvement1.

Differently from left heart IE, in which Streptococcus gallolyticus represents a main agent, the most common microorganisms reported in RHIE are Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative Staphylococci and group B Streptococci.2

In non-complicated cases, initial management should include antibiotics, as the clinical and imaging response is often seen within 6 weeks of therapy.2,6 A retrospective study has shown that vegetations whose major diameter <12mm in RHIE, commonly respond to medical treatment.2,7

Staphylococcus aureus must always be covered1 by the initial empiric antibiotic treatment. Initial treatment includes penicillinase-resistant penicillin, vancomycin or daptomycin in combination with gentamicin. Once the causative organisms have been isolated, therapy must be adjusted.

Consistent data showed that 2-week treatment may be enough and that the addition of an aminoglycoside may be unnecessary in non-complicated IE: methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; good response to treatment; absence of a) metastatic sites of infection or empyema, b) cardiac and extracardiac complications, c) associated prosthetic valve or left-sided valve infection; <20 mm vegetation length, absence of severe immunosuppression (<200 CD4 cells/mL) with or without acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).1The standard 4–6-week regimen must be used otherwise.1

There are no specific guidelines for pulmonary valve endocarditis, only for RHIE and, in particular, for tricuspid valve. Indications for surgery include 1) persistent bacteraemia and fever, despite appropriate parenteral antibiotic therapy; 2) locally invasive infections such as a perivalvular abscess; 3) hemodynamic instability; 4) progressive valve destruction and incompetence leading to heart failure; 5) tricuspid valve vegetations >20 mm that persist after recurrent pulmonary emboli with or without concomitant right heart failure.1,4,8,9

Our patient maintained hemodynamic stability and no signs of right heart failure during the first two admissions. In the first admission he was treated for a pneumonia, being the second admission the first time he was treated for infective endocarditis. On the third admission, there was pulmonary valve insufficiency, and the vegetation was >20mm, so he was proposed for surgery.

Overall, the prognosis for RHIE including isolated pulmonary valve infective endocarditis is generally better than left-sided IE.4,8 Vegetation length >20 mm and fungal aetiology were the main predictors of death in a large retrospective cohort of right-sided IE in IV drug users.4,11 In HIV-infected patients, a CD4 count <200 cells/mL has a high prognostic value.4,12,13

The actual risk of recurrence among survivors of IE varies between 2% and 6%. Right-sided IE has a high risk of recurrence in intravenous drug abusers (IVDA).1

Conclusion

We reported a case of PV IE in the absence of risk factors for RSIE and with an aortic prosthetic valve. Respiratory signs and symptoms were predominant, making the diagnosis more difficult. In general, prognosis appears to be more favorable than for left-sided IE. There are no guidelines for pulmonary valve endocarditis treatment specifically but the few case reports in literature usually describe a successful surgery after 4-6 weeks of antibiotic therapy.2,4,14,15

Figura I

Admission X-ray showing opacity on the right lung (left); thoracic CT showing an extensive right pneumonia (right)

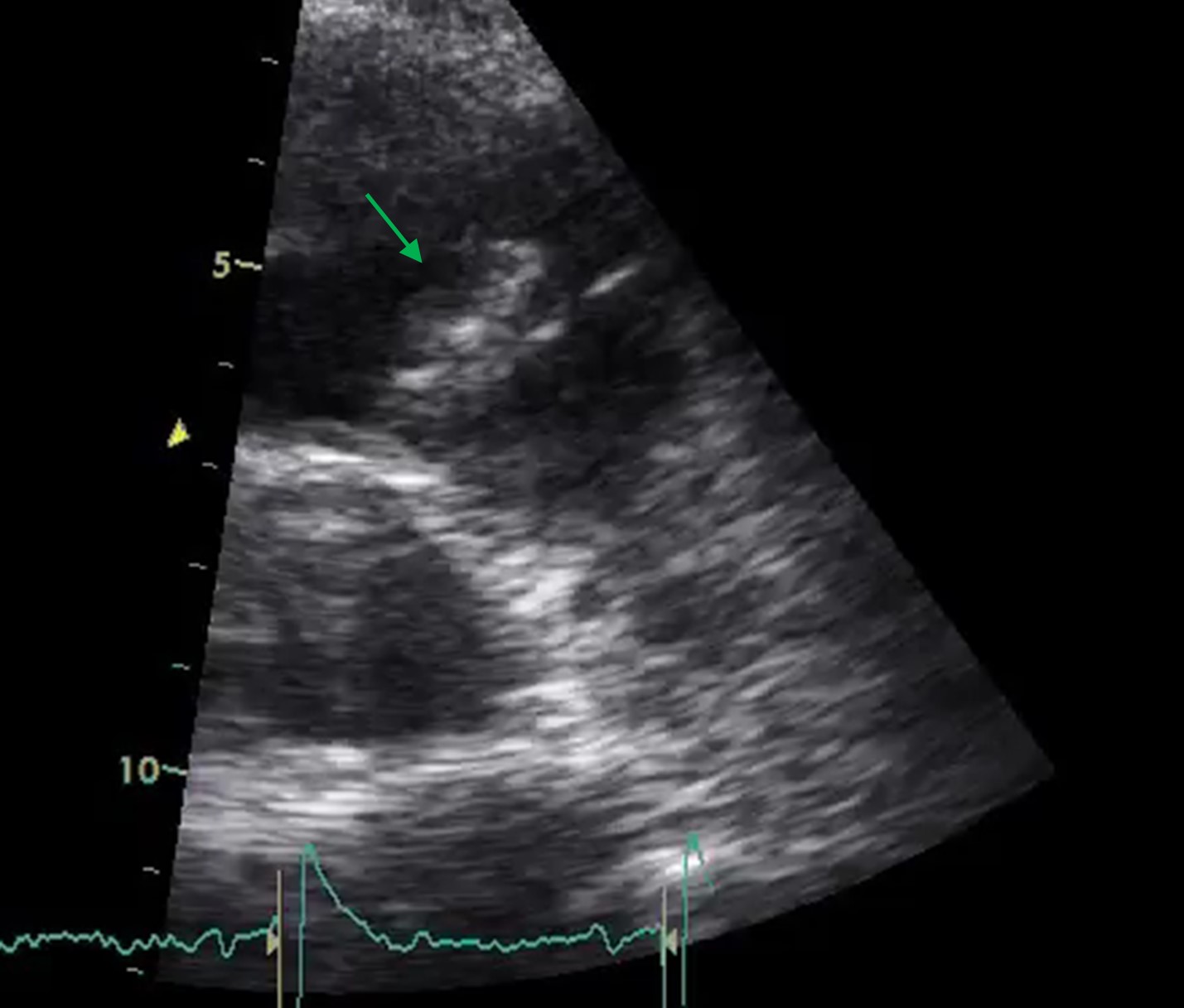

Figura II

Transthoracic echocardiogram: pulmonary valve vegetation leading to the diagnosis of endocarditis

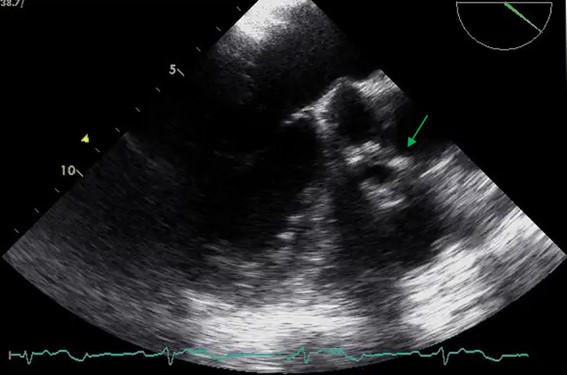

Figura III

Transesophageal echocardiogram: pulmonary valve endocarditis

BIBLIOGRAFIA

Referências bibliográficas:

1-Habib, G., et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis 2015; 3112- 3.

2-Seraj, S. M., Gill, E., & Sekhon, S. (2017). Isolated pulmonary valve endocarditis: Truth or myth? Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives,7(5), 329–31.https://doi.org/10.1080/20009666.2017.1374808

3-Cecchi. E.,et al,Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery, Volume 26, Issue 4, April 2018, Pages 602-09

4-Goud, A., Abdelqader, A., Dahagam, C., & Padmanabhan, S. (2015).Isolated pulmonic valve endocarditis presenting as neck pain.Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives,5(6), 29647.https://doi.org/10.3402/jchimp.v5.29647

5-Hatori, K., et al. Surgical case of isolated pulmonary valve endocarditis in a patient without predisposing factors. (2017) The General Thoracic Cardiovascular Surgery, Japanese Association for ThoracicSurgery DOI 10.1007/s11748-017-0788-7

6 - Ranjith MP, Rajesh KF, Rajesh G, Haridasan V, Bastian C,Sajeev CG,et al.Isolated pulmonary valve endocarditis: A case report and review of literature. J Cardiol Cases 2013; 8(5): 161-3

7-Pulmonary-valve endocarditis. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2224-5

8-Hecht SR, Berger M. Right-sided endocarditis in intravenous drug users. Prognostic features in 102 episodes. Ann Intern Med1992;117:560–6

9- Botsford KB, Weinstein RA, Nathan CR, Kabins SA. Selective survival in pentazocine and tripelennamine of Pseudomonas aeruginosa serotype O11 from drug addicts. J Infect Dis1985;151:209–16

10- Gaca JG, Sheng S, Daneshmand M, Rankin JS, Williams ML, O’Brien SM, Gammie JS. Current outcomes for tricuspid valve infective endocarditis surgery in North America. Ann Thorac Surg2013;96:1374–81

11-Botsford KB, Weinstein RA, Nathan CR, Kabins SA. Selective survival in pentazocine and tripelennamine of Pseudomonas aeruginosa serotype O11 from drug addicts. J Infect Dis1985;151:209–16

12 -Wilson LE, Thomas DL, Astemborski J, Freedman TL, Vlahov D. Prospective study of infective endocarditis among injection drug users. J Infect Dis 2002;185: 1761– 6

13 - Gebo KA , Burkey MD, Lucas GM, Moore RD, Wilson L. Incidence of riskfactors for clinical presentationand 1-year outcomes of infective endocarditis in an urban HIV cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006;43:426–32

14 - Hamza,N.,Ortiz,J.,&Bonomo,R.A.(2004).Isolated Pulmonic Valve Infective Endocarditis: A Persistent Challenge.Infection,32(3), 170–5.https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-004-3022-3

15 – Osaki J., Fumoto, H., Uchino M., Nakayama Y. (2021) Isolated Pulmonary Valve Endocarditis Accompanying Multiple Pulmonary Embolisms: Report of a Case. Kyobu Geka. 74(11):950-953