CASE DESCRIPTION

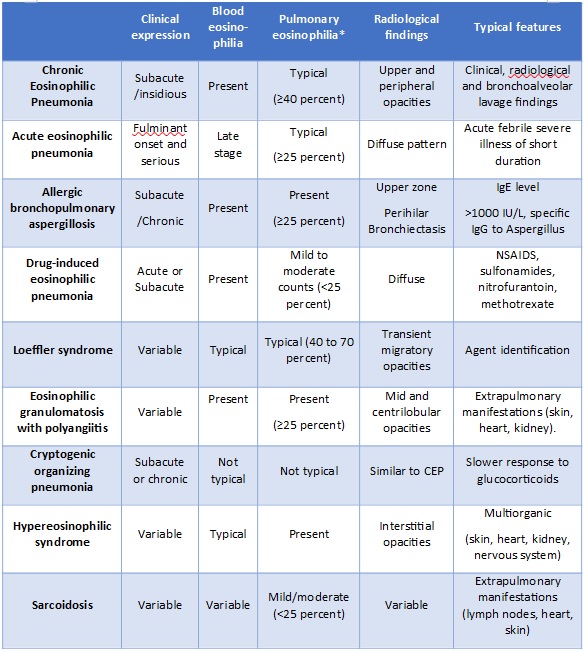

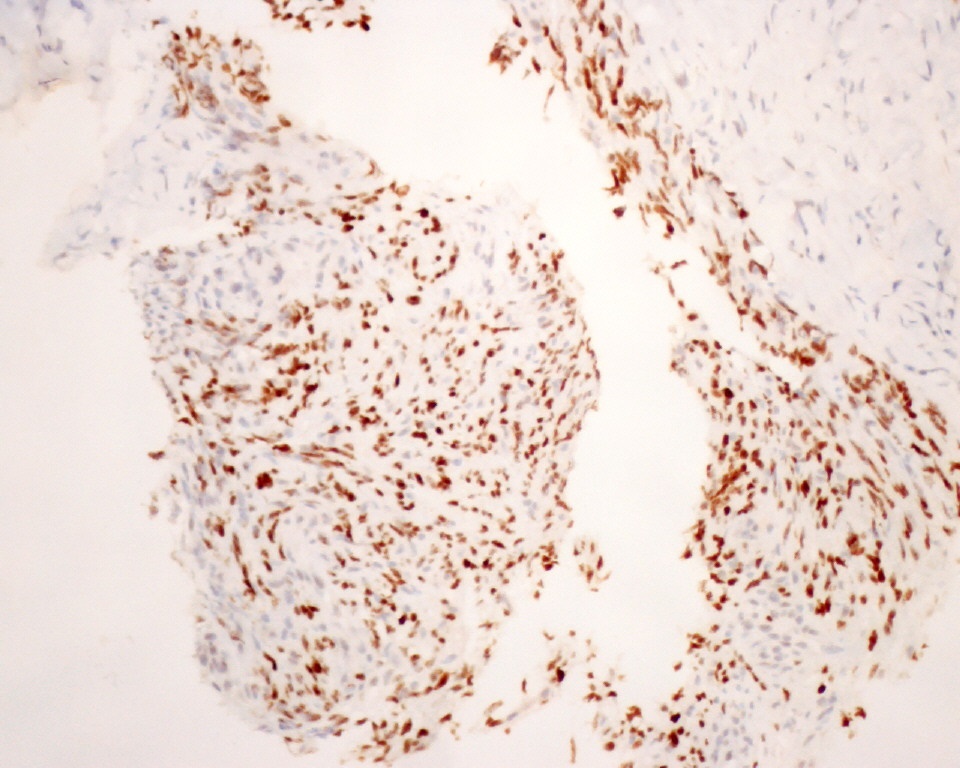

An 83-year-old black woman, born in Angola, without history of asthma, presented to the emergence department with progressive dyspnea, dry cough, asthenia and night sweats associated with respiratory failure, peripheral eosinophilia (27.9%, 9.01x10^9 eosinophils/L) and bilateral peripheral infiltrates of both lungs on chest x-ray. Thoracic Computed tomography (CT) revealed peripheral ground-glass opacities of lung parenchyma. (Fig. 1) Viral serology and baciloscopy on direct sputum examination did not isolate any organism.

Bronchofibroscopy shown no endobronchial alterations and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid revealed eosinophilic alveolitis (total cell count of 280 / mm3, with 45% eosinophils and a CD4 / CD8 ratio of 1:1). Direct mycobacteriological examination, culture and search for pneumocystis were negative. Cytology and Immunophenotyping study documented intense eosinophilia, without evidence of neoplastic cells. Parasitological examination of stool was negative. IgE levels were elevated (17200 ng/ml) and angiotensin-converting enzyme levels were normal. Peripheral blood (PB) smear revealed eosinophilia (27.9%, 9.01x10^9), activated lymphocytes, hypersegmented neutrophils with Döhle bodies, and flow cytometry immunophenotyping (IF) analysis of PB revealed eosinophils with markers of maturity, without clonal surface markers.Immunohistochemical analysis for BCR-ABL and alpha and beta-Platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) were negative.

The immunological study (including Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, Antinuclear antibody, complement, rheumatoid factor, anti-double stranded DNA) was unremarkable and serologic test for infections (including specific IgG for Aspergillus) were negative. Echocardiogram and pelvic echography did not reveal alterations. Respiratory function tests revealed a restrictive pattern. Although the patient has returned from Angola 20 years ago, serologic testing and empirical preventive treatment for strongyloidiasis (ivermectin 200 mcg/kg daily for two days, repeated at two weeks) was done while test results were pending. The serological result was negative.

The patient was diagnosed with chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (PEC), started corticosteroid therapy (CT) (pulses of methylprednisolone, followed by prednisolone 0.5 mg/kg/day) with clinical and radiological response.The patient was treated with prednisolone (15-25mg) for one year, and when the dose was reduced, she clinically relapsed with two severe exacerbations requiring hospitalization. One year after starting CT, she complained of erythematous-violaceus non-ulcerated non-painful nodular lesions with < 1 cm, on right hand and arm. (Fig. 2)

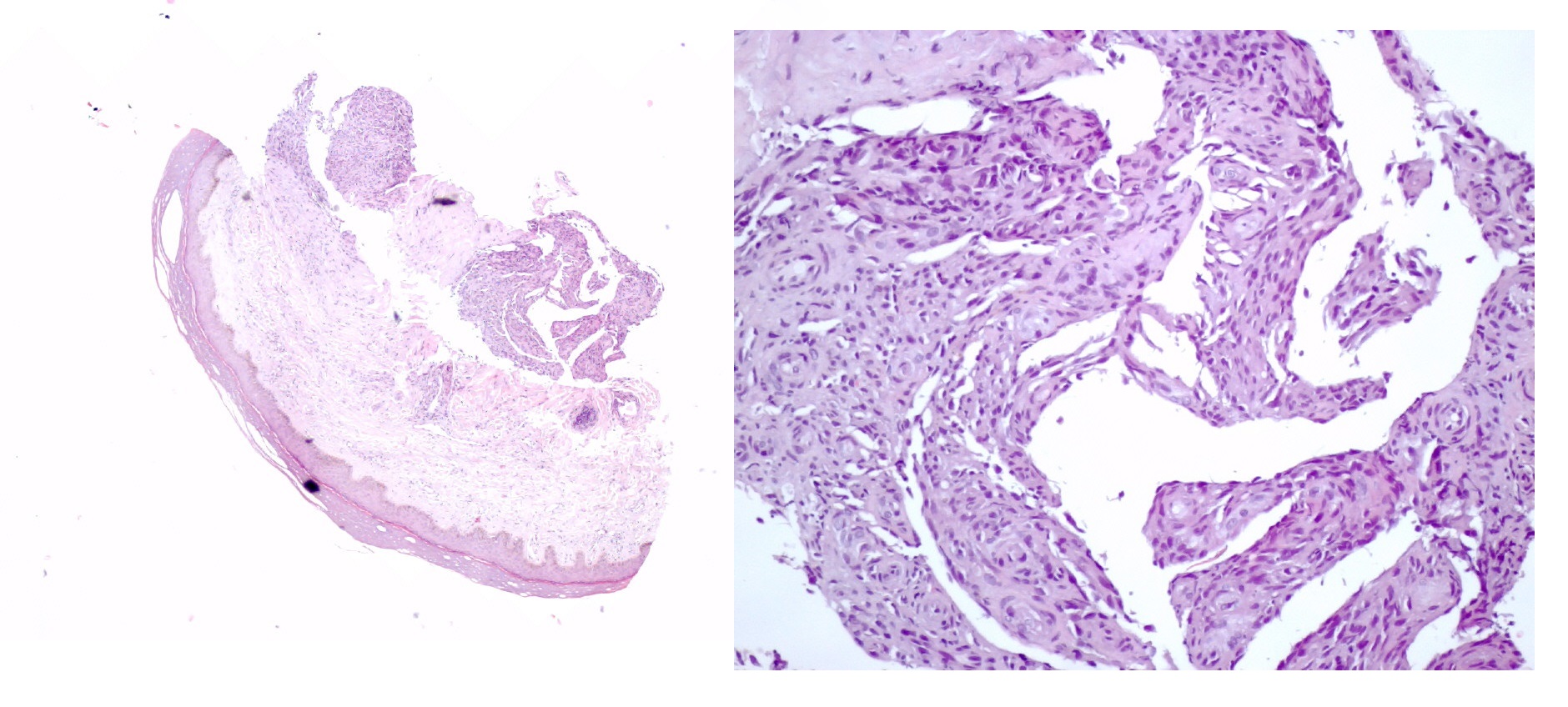

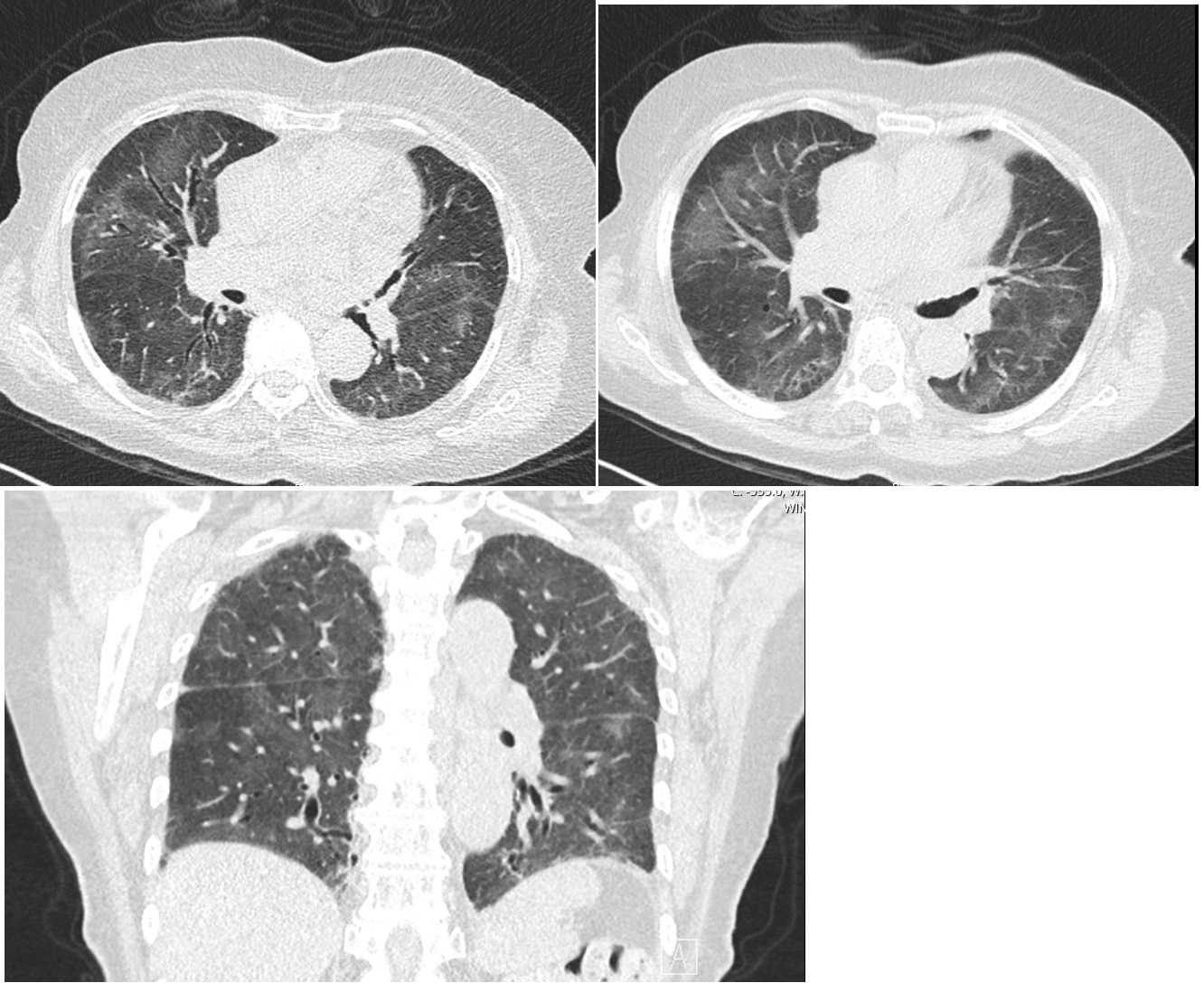

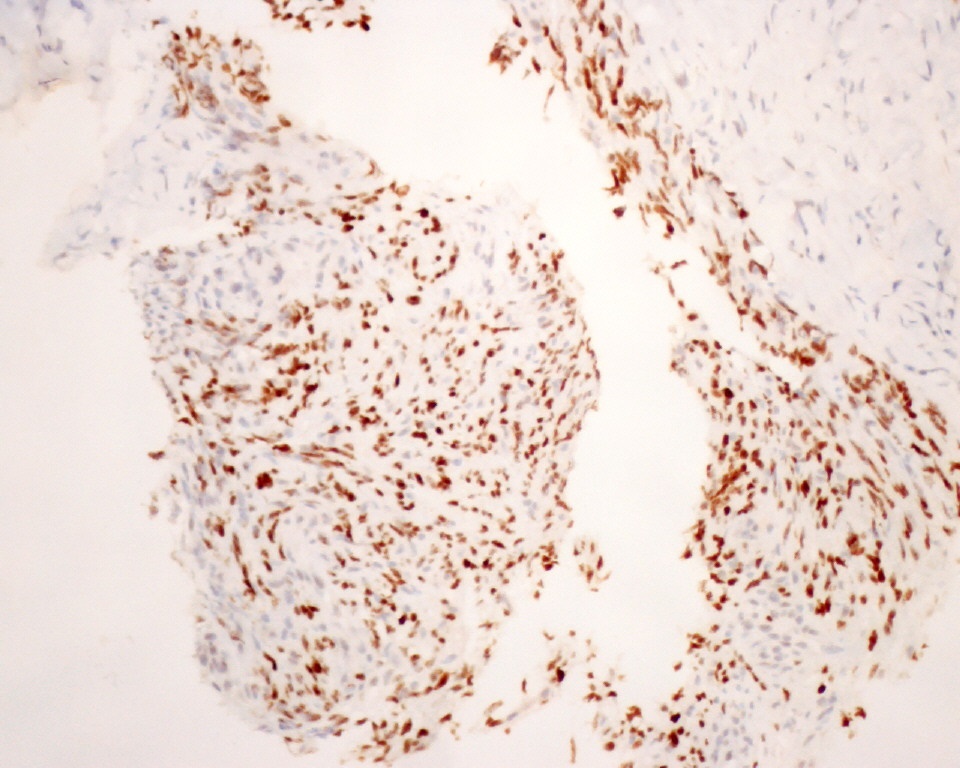

The biopsy revealed proliferation of vessels and spindle cells with cytological and immunohistochemical atypia consistent with kaposi sarcoma with diffuse expression of Human Herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8). (Fig. 3 and 4)

No mucous lesion or palpable lymph nodes were noted, and hemorrhagic, gastrointestinal or pulmonary complaints were not reported. Thoracic-abdominopelvic CT was requested and did not show relevant alterations for the clinical context. Blood count, renal and hepatic function were normal. Fecal occult blood test was negative.

A new IF analysis and quantification of specific immunoglobulin classes, as well as a serological study including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B and C, was performed and excluded infection and immunodeficiency specific disorders. Tryptase and Beta-2-mycroglobuline levels were normal.

Considering the localized disease with a low impact on the patient´s quality of life, systemic treatment was not required at that time, and she was oriented to Dermatology for local treatment. The patient was discharged with 20 mg of prednisolone as she did not tolerate further CT tapering but the possibility of skin or visceral progression is being continuously monitored. Regarding her clinical and functional phenotype, Omalizumab is being considered as an alternative therapy.

DISCUSSION

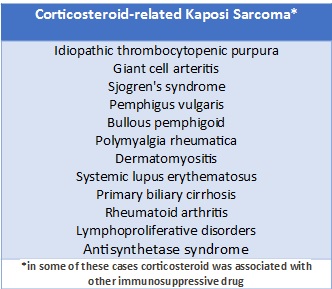

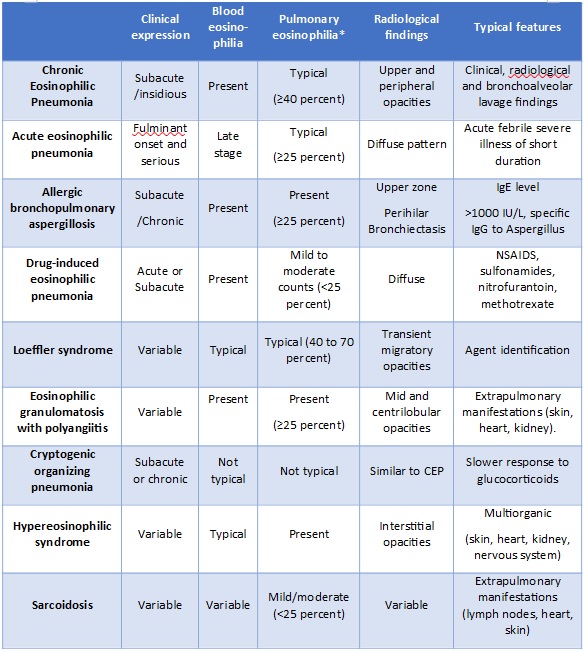

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP) is an idiopathic disorder characterized by an abnormal and marked accumulation of eosinophils in the interstitial and alveolar spaces of the lung .1 The diagnosis is typically based on the combination of clinical presentation, chest imaging showing predominantly peripheral or pleural-based opacities, and a bronchoalveolar lavage cell count showing eosinophilia (≥25 percent).1-4 The differential diagnosis of CEP includes several diseases, including Infections and drug-induced pulmonary eosinophilia (Table 1) and lung biopsy is not necessary unless the BAL does not show eosinophilia, the chest imaging features are atypical, or the patient doesn´t respond promptly to systemic glucocorticoid therapy.1-4 Subjective and radiographic improvement usually starts within 48 hours of initiating therapy. However, most patients require prolonged treatment (more than six months) and up to three-fourths of patients will require ongoing therapy for several years.5,6 Alternative therapies have been explored for patients with recurrent flares of CEP.

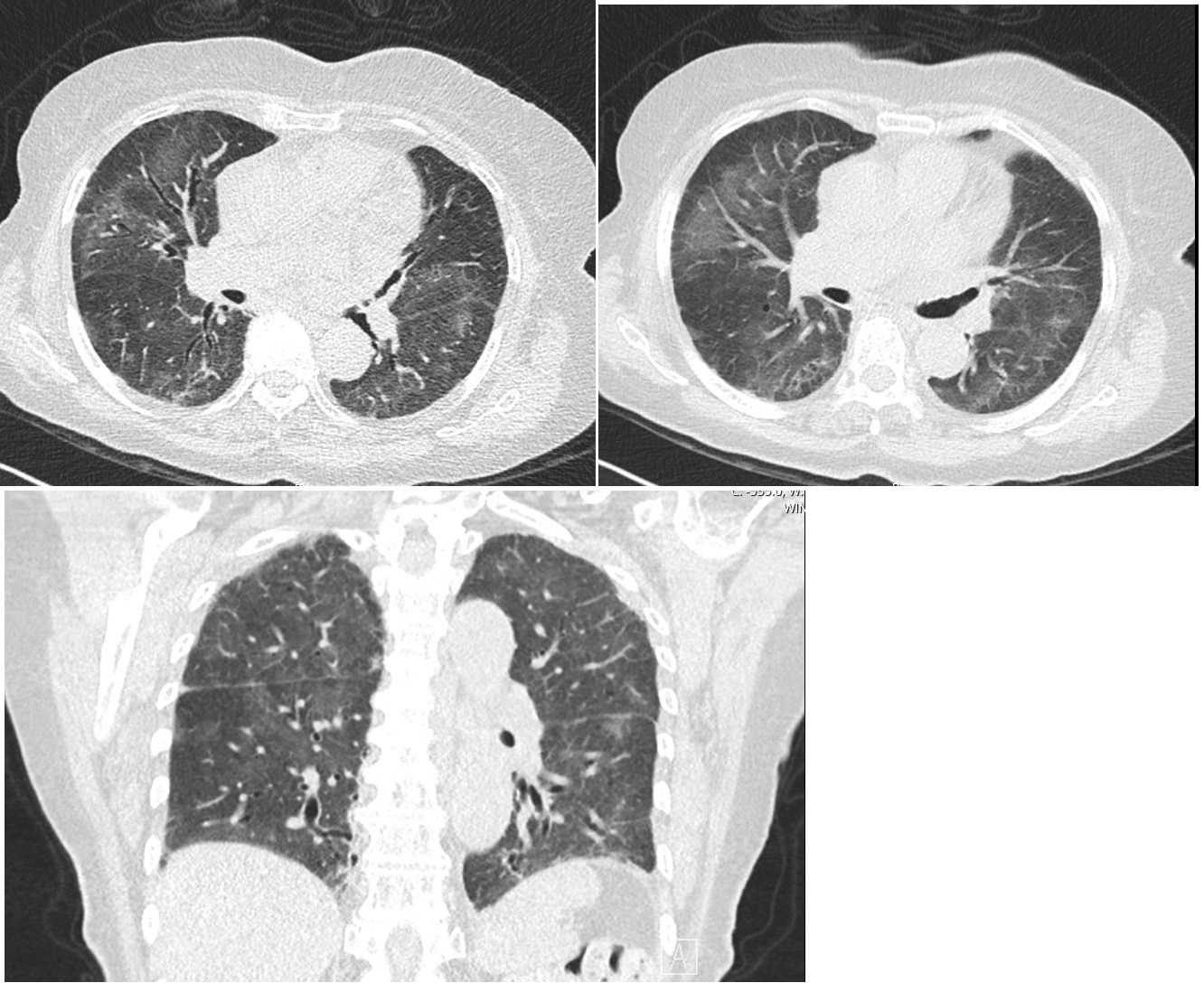

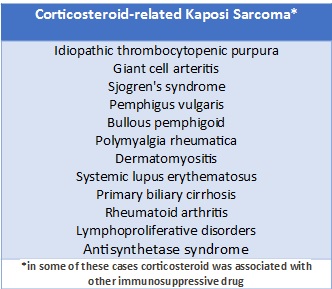

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is an angioproliferative disorder with four variants: classic, endemic, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related, and iatrogenic.7 The latter is more likely in patients with immunosuppressive treatments for organ transplantation, however, it has also been reported in haematological, rheumatological, and pulmonary diseases requiring immunosuppressive treatment, including corticosteroid therapy. (Table 2).7-11

According to the literature, the effects of glucocorticoids are two-fold: the up-regulation of Kaposi cell proliferation and the activation of HHV-8. Glucocorticoid (GC) stimulates the development of growth factors and increases the expression of regulator GT receptors on KS cells.11 Additionally, it inhibits transforming growth factor beta, a protein that inhibits growth of endothelial cells, thus up regulating KS cell proliferation and inducing KS lesions. Furthermore, excess of glucocorticoids seems to be implicated in activation of HHV-8 replication, thus predisposing to opportunistic infections.8,11

It is challenging to evaluate the relationship between the type, dosage and duration of immunosuppressive medication and the onset of KS.The interval between the initiation of steroid therapy and the development of KS has been reported as 3 to 36 months, the average being 4 months.12In the rare cases reported, glucocorticoid doses range from prednisolone 15mg/d to 80mg/d, but at least one case of iartrogenic KS after prednisolone 7.5mg and methotrexate 10mg for the treatment of giant cell arteritis was reported.13Above all, the importance of the cumulative dose as a determining factor is questioned, but further studies are needed.

We emphasize not only the singularity of this case report, but especially the diagnostic and therapeutic challenge including the importance of rule out other reasons for pulmonary eosinophilia (Table 1), as well as investigating other causes of immunosuppression.

Moreover, the link between eosinophilic pulmonary diseases, KS and Corticosteroid therapy has not yet been reported. In fact, leukocytic infiltration and vascular slits are important criteria for recognition of KS under light microscopy and KS has been reported in few eosinophilic dermatologic diseases8. We highlight that in this case, KS might be associated not only with CT, but also with the immune dysregulation underlying allergic and autoimmune diseases and, in particular, eosinophilic disorders. Furthermore, the patient’s advanced age and race could have a role in disease’s pathogeny and expression. Despite the endemic variant could be thought, the temporal relation of clinical manifestation of PEC and start of treatment is unquestionable even if it represents the trigger for the onset of the disease.

Regarding the diagnostic approach, we emphasize the need to exclude more severe organic manifestations, as these have been described in cases of iatrogenic KS.8-10

The initial evaluation of a patient with KS consists of a thorough physical examination with special attention paid to those areas typically affected by the disease, such as the lower extremities, face, oral mucosa, genitalia, gastrointestinal tract, and lungs.

There is no consensus staging for immunosuppression-associated KS and the tests and recommended applicable criteria are usually the same as for HIV-associated KS.Chest X-ray is recommended and, in the event of abnormalities suggestive of respiratory compromise, bronchoscopy or computed chest tomography should be performed. It is also recommended to rule out fecal occult blood; if this test is positive, digestive endoscopy should be performed. All patients who present with Kaposi sarcoma should be evaluated for underlying immunodeficiency and undergo HIV screening.14

The most commonly utilized staging system for AIDS-related KS was developed by the AIDS Clinical Trial Group (ACTG) of the National Institute of Health and is based on disease extension, CD4T-cell count, and systemic compromise (opportunistic infections, B symptoms such as fever, weight loss, or persistent diarrhea, and Karnofsky performance status below 70 points).14

Therapeutic strategy assents in Immunosuppressive drug reduction/withdrawal combining with close surveillance for systemic progression, which is challenging in this case. The therapeutic dilemma inherent in the long-term use of corticosteroid therapy in several rheumatologic and allergic diseases, is highlighted, with iatrogenic KS being a serious example of its effects.

Alternative therapies have been explored for patients with recurrent flares of CEP, including high-dose inhaled glucocorticoids, omalizumab (monoclonal antibody to IgE),15and mepolizumab (monoclonal antibody to interleukin-5).6 Further study is needed to determine the efficacy of this therapy.

As main message, we conclude that Kaposi´s sarcoma is not just associated with severe immunosuppression and HIV, but may appear in many apparently immunocompetent patients taking “low-dose” corticosteroids. Conversely, given the incidence of relapse and the potential for steroid-induced side effects or fibrotic changes long term, further investigation of steroid-sparing therapies such as anti-IL5 antibodies are needed.

LEARNING POINTS

• Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a Human Herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)-associated tumor that must be considered in all patients with immunosuppressive therapy, including in immunocompetent ones, where the use of corticosteroids should be checked.

• KS might be associated not only with corticotherapy but also with the immune dysregulation underlying immunoallergic and autoimmune diseases, especially in susceptible individuals, attending on race, age and genetic factors.

• The differential diagnosis of pulmonary eosinophilia includes Chronic Eosinophilic pneumonia, infections, vasculitis, sarcoidosis and hypereosinophilic syndrome, and the link between these diseases and immunossupression-associated tumors, including KS, should be reminded.

Figura I

Table 1- Differential diagnosis of CEP (* the percentage values refer to eosinophil count) NSAIDs -Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Figura I

- High-resolution Thoracic Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed bilateral peripheral ground-glass opacification of lung parenchyma (upper and lower lobes) with areas of subpleural reticulation.

Figura II

-Violaceus non-ulcerated non-painful nodular lesions with well-defined edges and < 1 cm, on the third finger of the right hand (left panel), and on the ulnar aspect of the right arm (right panel).

Figura II

Table 2 Corticosteroid-related Kaposi Sarcoma

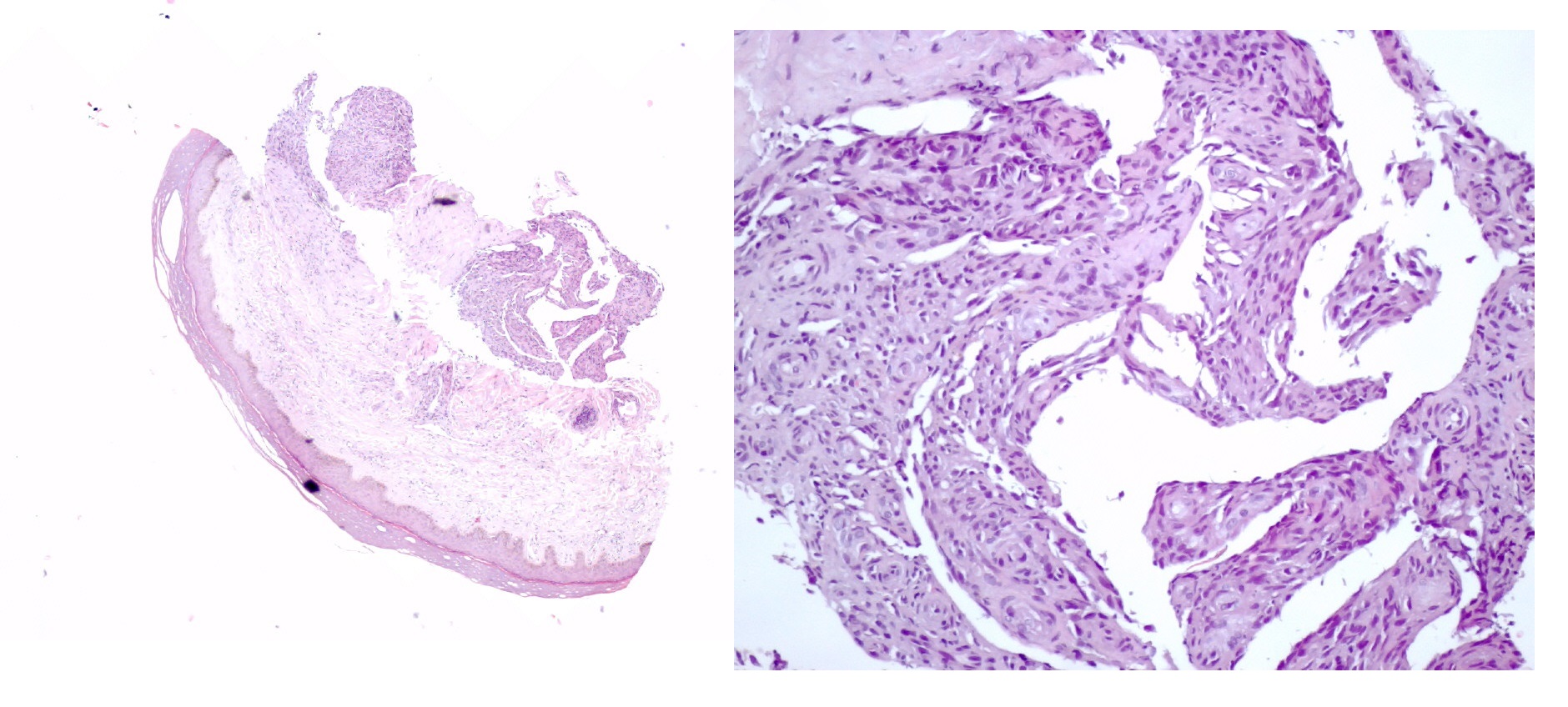

Figura III

- Histologic examination revealed whorls of spindle-shaped cells with leukocytic infiltration and neovascularization with aberrant proliferation of small vessels. (hematoxylin and eosin stain, x40 on left and x200 on the right).

Figura IV

- Immunohistochemical analysis of biopsy revealed diffuse expression of Human Herpesvirus-(8 x200).

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Bento J, Botelho C, Souto Moura C, Morais A. Pneumonia eosinofílica crónica Acta Med Port 2010; 23: 1133-40.

2. Crowe M.,Robinson D, Sagar M, Chen L, Ghamande S. Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia: clinical perspectives. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management 2019:15 397–403.

3. Magalhães E, Tavares B, Chieira C. Pneumonias eosinofílicas. Rev Port Imunoalergologia 2006; 14 (3): 196-217.

4. Teixeira N, Santos M, Pedro F, Pinto MJ, Mestre A. Idiopathic Chronic Eosinophilic Pneumonia. Cureus 2021; 13(3): e14047.

5. Oyama Y, Fujisawa T, Hashimoto D, Enomoto N, Nakamura Y, Inui N, et al. Efficacy of short-term prednisolone treatment in patients with chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(6):1624.

6. Suzuki Y, Suda T: Long-term management and persistent impairment of pulmonary function in chronic eosinophilic pneumonia: a review of the previous literature. Allergol Int. 2018; 67:334-40. 10.1016.

7. Antman K and Chang Y. Kaposi’s sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342: 1027–038.

8. Senhaji G, Elloudi S, Gouzi I, Hammas N, Kassel J, El Jouari O, et al. Iatrogenic Kaposi Sarcoma: A Case Report in a Non Organ Transplant Patient. SM J Case Rep. 2019; 5(1): 1091.

9. Binois R, Nadal M, Esteve E, De Muret A, Kerdraon R, Gheit T, et al. Cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma during treatment with superpotent topical steroids and methotrexate for bullous pemphigoid: three cases. Eur J Dermatol. 2017; 27: 369-74.

10. Lazzarini R, Lopes AS, Lellis RF, Brasil F. Iatrogenic Kaposi’s sarcoma caused by corticosteroids. An Bras Dermatol. 2016; 91: 867-9.

11. Guo W‐X, Antakly T, Cadotte M ,Kachra Z,Kunkel L,Masood R, et al. Expression and cytokine regulation of glucocorticoid receptors in Kaposi´s sarcoma. Am J Pathol.1996; 148;1999 –2008

12.Louthrenoo W, Kasitanon N, Mahanuphab P, Lertlakana B,Thongprasert S. Kaposi’s sarcoma in rheumatic diseases.Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2003;32: 326–333.

13. Espadafor-López B, Cuenca-Barrales C, Salvador-Rodriguez L, Ruiz-Villaverde R. Iatrogenic Kaposi´s Sarcoma Successfully Treated with Topical Timolol. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2020 Mar;111(2):176-178.

14. Requena C, Alsina M, Morgado-Carrasco D, Cruz J, Sanmartín O, Serra-Guillén C, et al. Sarcoma de Kaposi y angiosarcoma cutáneo:directrices para el diagnóstico y tratamiento. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:878--887

15.Domingo C, Pomares. Can omalizumab be effective in chronic eosinophilic pneumonia? Chest. 2013;143(1):274