Introduction

Malignant mesothelioma (MM) is an aggressiveand rare neoplasm1-4arising from serosal membranes.The pleura is the most common location, followed by the peritoneum and, in a small percentage, the pericardium and the tunica vaginalis1,2.

Primary malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPM) was first described by Miller and Wynn in 19082and has an incidence of 1.2-1.3 per million per year3in Europe, mainly affecting men1-3in the fifth and sixth decades of life2,3.

Asbestos exposure is the most widely recognized risk factor for MM5, however, only 33% of MPM cases have a known history of asbestos exposure1. Clinical presentation and radiologic features are usually nonspecific, making its diagnosis a challenge4. Furthermore, the differential diagnosis for ascites is wide and malignant-induced ascites is uncommon, with MPM being responsible for only 1% of the cases5. The definitive diagnosis of MPM relies on histologic and immunohistochemical analysis.

Herein, we describe a case of an 85-year-old man with no known prior asbestos exposure, having a 2-week progressive abdominal distension and heartburn, being diagnosed with ascites secondary to MPM.

Case Report

An 85-year-old caucasian man, a former construction worker. He went to the emergency department with a 2-week history of abdominal distension and heartburn. He denied nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, gastrointestinal blood loss, anorexia, weight loss, fever, asthenia, thoracic pain, and respiratory complaints. He had no recent travels outside Portugal and denied contact with any sick person. He was an ex-smoker (5 pack-year history) and had a 40-year history of alcohol consumption of about 50g/day, without known history of asbestos exposure. Thirteen years before, he had had a surgical resection of a dorsal ependymoma, complicated with paraplegia and no relapse.

On admission, he was afebrile, with a blood pressure of 119/84mmHg and a pulse rate of 70 beats/min. His oxygen saturation was 95% on room air.Abdominal examination revealed ascites without signs of collateral circulation. He had no rash, and no palpable lymphadenopathy was found.

Blood analysis showed mild anemia (hemoglobin 11.3g/dL) with iron and folic acid deficiency, low serum albumin (2.3g/dL), elevated C-reactive protein (101.5mg/L) anderythrocyte sedimentation rate (55mm/h). White blood cells (WBC) and platelet counts, coagulation tests, serum bilirubin(total and conjugated), aspartate and alanine aminotransferases, lactate dehydrogenase and serum pancreatic enzymes were within normal range. Albumin-to-creatinine ratio was 110mg/g. Thyroid and renal functions were normal. Hepatitis B and C and human immunodeficiency virus infection were excluded. Immunological study was negative. Abdominal ultrasound was inconclusive, and an abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous contrast was performed, showing large ascites and signs of chronic hepatopathy, and excluding other lesions.

Paracentesis was performed and yellowish ascitic fluid was obtained; analysis serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) was 0.7g/dL, with high total protein (4.4g/dL), low glucose (65mg/dL), high lactate dehydrogenase (309U/L), normal amylase (43UI/L) and adenosine deaminase (32UI/L). Differential cell count was 610WBC/mm3with lymphocyte predominance (51%). Ascitic cytology was negative for malignancy; cultures, including for acid-fast bacilli, were negative. Bacterial DNA ofMycobacterium tuberculosiswas not detected by polymerase chain reaction amplification on ascitic fluid.

Thoracic CT scan, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and colonoscopy were normal.

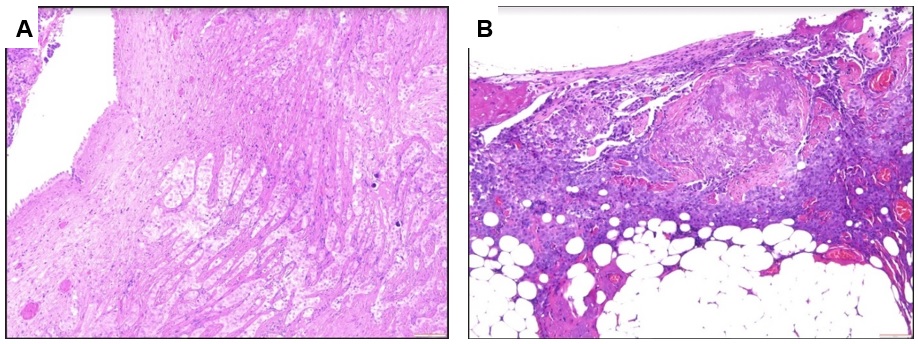

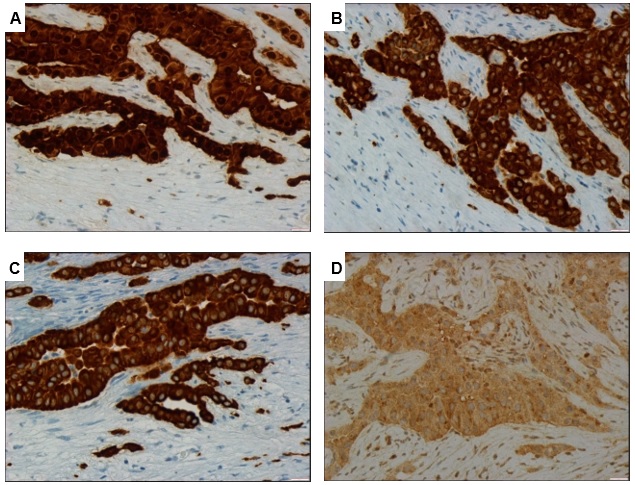

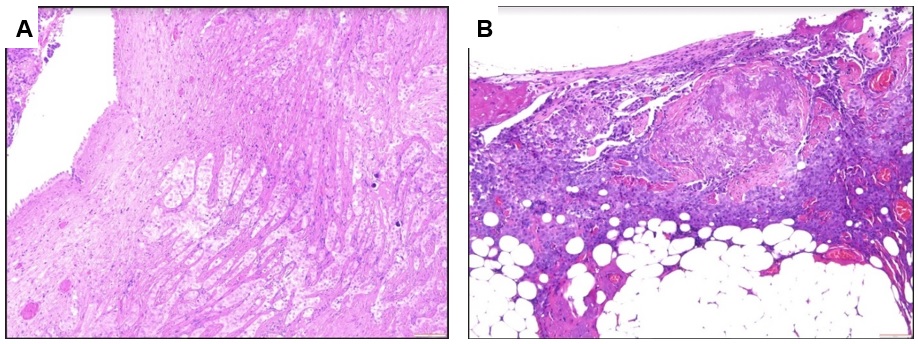

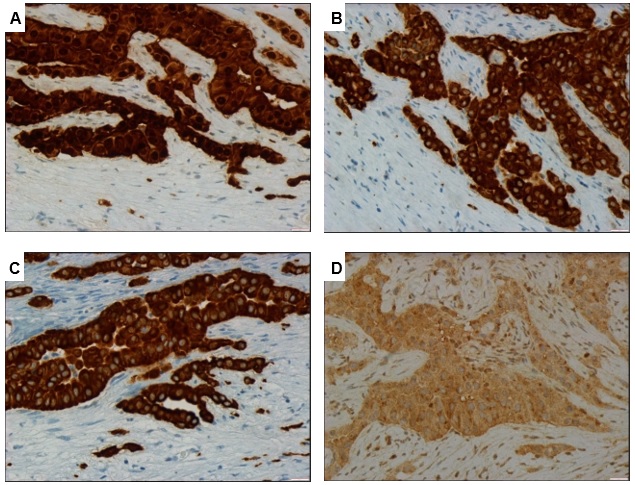

The etiology remained unknown, therefore a laparoscopy was performed: at inspection, the peritoneum appeared thickened; biopsy of peritoneum has been performed and six liters of serous ascitic fluid were removed. On histologic (Figure 1) and immunohistochemical analysis, MPM – epithelioid subtype was diagnosed. Tumor cells were positive for calretinin (Figure 2A), cytokeratin 5/6 (Figure 2B), podoplanin andWilms’ tumor 1 antigen(WT1), and they were negative for cytokeratin 20, PAX-8 and Ber EP4 (Figure 2C). Tumor cells also showed a nuclear loss ofBRCA-1 associated protein 1(BAP1) (Figure 2D).

The patient was referred to the Oncology Department but, unfortunately, he died one week after diagnosis before any specific treatment could be administered.

Discussion

MPM is a highly aggressive neoplasm, often diagnosed at advanced stages; its diagnosis is a challenge in clinical practice, owing to its rarity and to the lack of specific clinical and radiological features4.

There is a wide variety of symptoms: abdominal pain2-5, abdominal swelling secondary to ascites2,4,5, asthenia, weight loss2-5and anorexia2,3are the most frequently reported. Other common complaints are fever2-4, diarrhea3, vomiting3,4and night sweats4.

There is no definitive imaging diagnostic modality2-4, however, abdominal CT with intravenous contrast is the preferred first line approach2,4. CT scan usually shows ascites4and, in some cases, a thickening and caking of the omentum2,4, mesenteric nodules2of various sizes and shapes4,and a peritoneal mass2,4. CT is also useful for detecting and characterizing peritoneal masses, as well as for guiding biopsies4.

The differential diagnosis for ascites is wide, and peritoneal fluid exam is essential in the diagnostic work-up. The patient had chronic liver disease, which could explain the ascites. However, in this case, SAAG was 0.7g/dL, pointing for etiologies not due to portal hypertension, such as peritoneal carcinomatosis, peritoneal tuberculosis, pancreatitis, and nephrotic syndrome and serositis5.

Cytologic examination of ascitic fluid is recommended in case of suspicion of neoplasm, or when the underlying etiology is not clear. However, although its sensitivity is high, a negative result does not exclude neoplasm. Furthermore, ascitic fluid cytology in patients with MPM has a low diagnostic yield1,4and it is often inconclusive4.

For a definitive diagnosis of MPM, pathologic evaluation with histologic and immunohistochemical analysis is needed2,4.MPM has three pathologic subtypes: epithelial (56%), sarcomatous (32%) and mixed (13%)1. In the presented case, MPM – subtype epithelioid was diagnosed upon a biopsy by laparoscopy. Epithelioid subtype has a frequently better outcome than sarcomatous or mixed subtypes3,4. However, advanced age and male gender are unfavorable prognostic factors for survival4, as seen in our patient.

This casehighlights the importance of considering MPM in the differential diagnosis of malignant ascites, mostly when the etiology is not obvious, and the crucial role of biopsy by laparoscopy for the definitive diagnosis.

Soon after diagnosis, treatment should be initiated. Cytoreductive surgery with heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy (CRS-HIPEC) is the gold standard treatment2-4, but it is only possible in selected patients3,4. The treatment decision is based on the performance status, the histologic type of MPM, and the ability to achieve complete or near complete cytoreduction during surgery. A segmental obstruction of the small bowel or tumor higher than 5 cm of diameter on the small bowel surface or adjacent to the mesentery of the jejunum or ileum predict a lower likelihood of achieving complete cytoreduction. Treatment with CRS-HIPEC should be the choice in patients with good performance status, with epithelioid subtype, amenable to complete cytoreduction and without metastatic disease.4

Unfortunately, for most patients the prognosis remains poor, with a median survival of 1 year1,4.Further research is needed for finding therapies that ameliorate patients and improve prognosis.

Figura I

Histological features of the peritoneal biopsy. Photomicrograph showing (A) nests of neoplastic large cells characterized by an abundant cytoplasm and oval nuclei with visible nucleoli, without atypia; (B) necrotic area and tumor cells infiltrating the adjacent adipose tissue is present. (H&E staining, original magnification x100)

Figura II

Immunohistochemical analysis of the peritoneal biopsy. (A) staining with calretinin shows positive nuclear and cytoplasmic reactivity; (B) staining with CK 5/6 shows positive membranous and cytoplasmic reactivity; (C) neoplastic cells are positive for CK7, WT1 and podoplanin and negative for CK20, PAX-8 and Ber EP4; (D) loss of nuclear expression of BAP1 in neoplastic cells, with preserved expression of BAP1 in adjacent benign cells. (Original magnification x400 [A-D]). CK, cytokeratin. WT1, Wilms’ tumor 1 antigen. BAP1, BRCA-1 associated protein 1.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Shih CA, Ho SP, Tsay FW, Lai KH, Hsu PI. Diffuse malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2013 Nov; 29:642-5.

2. Abbas H, Rodriguez JC, Tariq H, Niazi M, et al. Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma Without Asbestos Exposure. Gastroenterol Res. 2019;12(1):48-51.

3. Sousa SM, Pereira F, Duarte M, Marques M, Vázques D, Marques C. Malignant Peritoenal Mesothelioma as a Rare Cause of Dyspeptic Complaints and Ascites: a Diagnostic Challenge. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2020; 27:197-202.

4. Kim J, Bhagwandin S, Labow DM. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: a review. Ann Transl Med. 2017; 5(11):236.

5. Wong KA, Olson KA, Chak EW. An Unusual Cause of Abdominal Ascites. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2018; 12:420-4.