Introduction

Septic arthritis (SA) has its pathophysiology most commonly associated to hematogenous dissemination, frequently affecting large and more vascular joints. Sternoclavicular joint (SCJ) is a rare site for infection, accounting for only 1% of all cases of SA and 17% of those are related with intravenous drug use.1,2 Sternoclavicular variant presents generally in a subacute fashion, it frequently leads to serious complications such as osteomyelitis or mediastinitis.3 Diagnostic workup includes preferentially a computer tomography (CT) imaging.4 Management consists on antibiotic therapy and, in last instance, surgical debridement.5 Staphylococcus aureusis responsible for about 50% of cases, followed by Pseudomonasaeruginosaand other gram-negative bacteria.Enterococcus faecalis (EF)is a gram-positive bacteria responsible for a variety of nosocomial and community acquired infections, however it is seldom associated with SA.1Here we report a case of an EF sternoclavicular SA in an adult man with a cystostomy.

Case Presentation

A 57-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ER) of our hospital complaining of pain, swelling and erythema near the left SCJ. His medical history was almost unremarkable, except for an asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis and a cystostomy due to urethral stenosis. His family history was non-contributory, there was no record or stigma of intravenous drug use. CT of the chest described an eventual ongoing process of cellulitis surrounding the left paramanubrial area. At this time the patient was discharged with a 7-day course of oral amoxicillin-clavulanate.

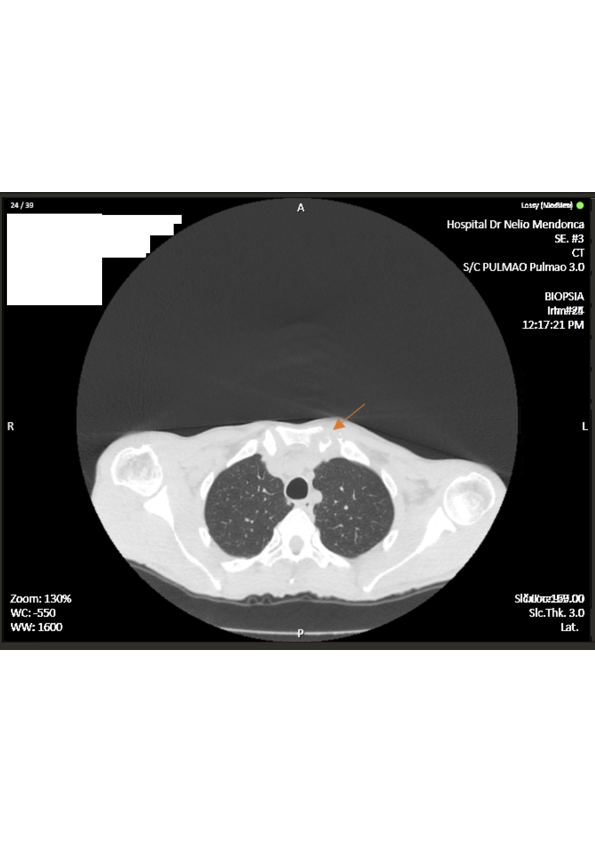

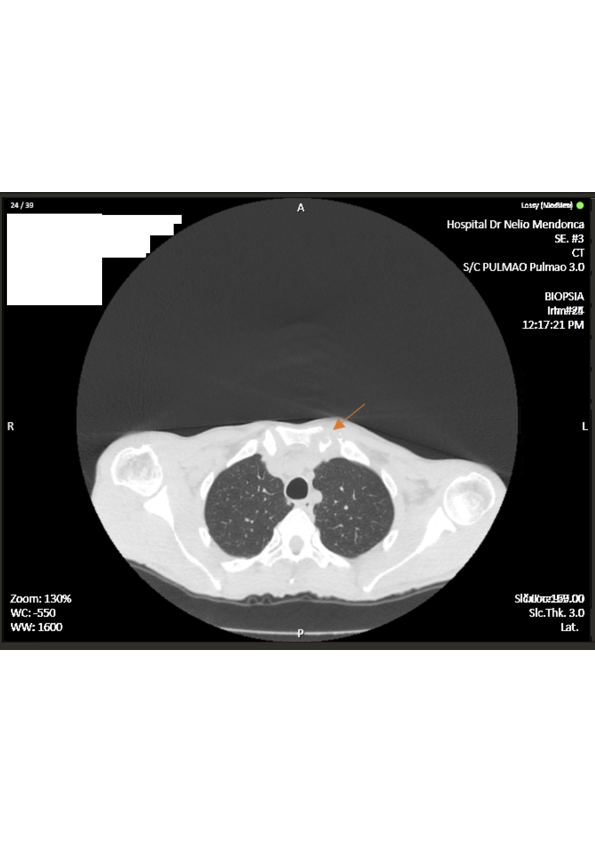

Two months later, he returned to the ER with persistent symptoms, in addition to progressive restricted abduction of his left shoulder, weight loss of 7kg, chills and diaphoresis. The physical examination revealed a tympanic temperature of 38.1ºC, tachycardia and an holosystolic murmur. Inflammatory signs were visible near the left SCJ with edema, erythema and warmth. His blood results revealed a normocytic anemia, leukopenia, elevated C reactive protein level (CRP) of 75 mg/L and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 62 mm/h and urine analysis with leukocyturia. The patient was admitted for further studies. Repeat chest CT (Fig. 1) revealed structural bone irregularities with lytic and erosive subchondral lesions on the left SCJ. Serology tests for HIV, Tuberculosis and Brucellosis were all negative. Blood and urine cultures were both positive for an EF with the same antibiotype.

(Inserir figura nº 1 aqui)

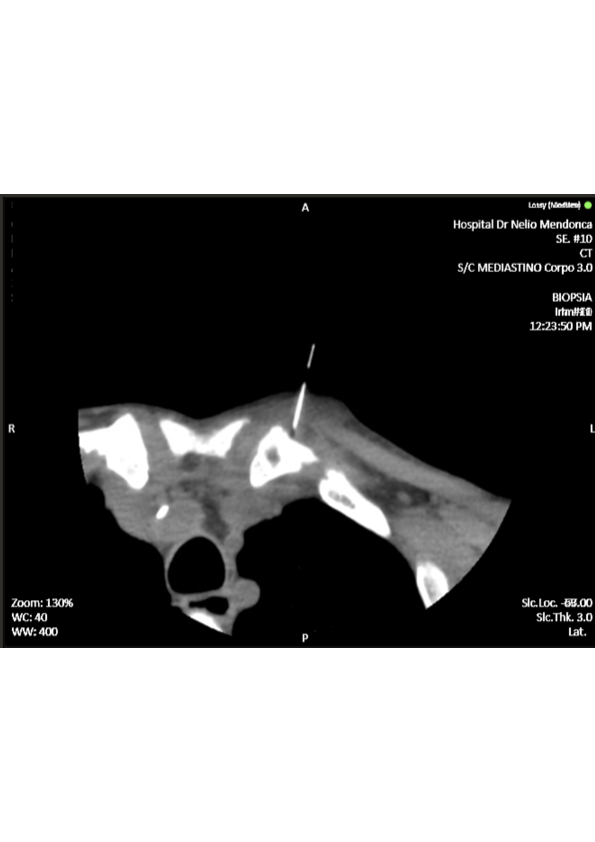

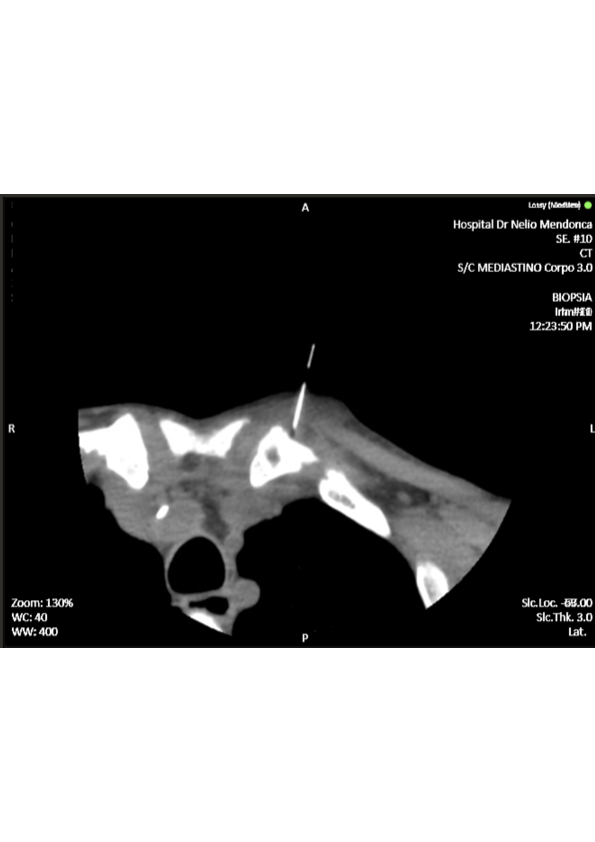

We ordered a CT-guided bone biopsy of the left SCJ lesions (Fig. 2), but incidentally the sample was not sent for microbiology and gram stain analysis, not being possible to isolate the agent. However, we managed to have the anatomopathological study, reporting findings suggestive of clavicular osteomyelitis with acute inflammatory areas and fibrous exudate. Transthoracic echocardiogram was negative for vegetative lesions or other signs of concomitant endocarditis.

(Inserir figura nº 2 aqui)

We assumed the diagnosis of sternoclavicular septic arthritis, complicated with osteomyelitis due to an EF bacteremia. The patient was started on directed antibiotic treatment with intravenous gentamicin (320mg/day) and ampicillin (2g/4h) for four weeks. Suprapubic cystostomy was replaced by the Urology team. During this period of treatment, both CRP and ESR level decreased progressively, in addition to complete resolution of symptoms. After 30 days of hospitalization for IV antibiotics, he was discharged on an additional two weeks of oral amoxicillin (1g/8h). On the follow-up visit, one month later, he did not show any signs of recurrence and inflammatory markers remained negative. Surgical debridement was not necessary.

Discussion

Sternoclavicular SA is a rare entity, but for unclear reasons has higher incidence in intravenous drug users. There are other risk factors for sternoclavicular SA, such as immunocompromised status, trauma, and contiguous or distant infectious foci. Most SA is thought to arise from hematogenous seeding of synovium. It can be caused by a variety of pathogens with Staphylococcus aureus being the leading agent, followed by Pseudomonasaeruginosa and other gram-negative bacteria. Nevertheless, the rarity of enterococcal arthritis is noteworthy in view of the frequency of enterococcal bacteremia and the high prevalence of this pathogen in many nonarticular infections.2,6 John J. Ross, et al, reviewed 180 cases of sternoclavicular SA, reported in the literature between 1970 and 2004, not mentioning any case of EF sternoclavicular SA.1 In addition, we could not identify other recent reports using PubMed (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD) search engine.

Our patient’s urinalysis and urine culture suggest a urinary tract source of an EF. Enterococcal bacteremia alone does not appear to be sufficient to establish septic arthritis. Therefore, there’s a number of potential predisposing risk factors, including alcoholism, osteoarthritis, systemic glucocorticoid, rheumatoid arthritis and prosthetic joints.1,6 Despite not having any of this predisposing risk factors, the patient had a long term cystostomy which likely induced chronic seeding of EF.

A detailed clinical history is paramount, since other non-infectious systemic pathologies can mimic this entity or predispose for its occurrence.7,8 Sternoclavicular SA can present with fever, joint swelling and restricted range of motion, most cases are unilateral, preferentially on the right side.9 There is most of time a diagnostic delay, with a mean duration of symptoms at presentation of around 14 days that can be attributed to clinical ambiguity and slow disease progression which can partly be explained by the SCJ anatomy that prevents the formation of large effusions.10 Infection is well established at the time of diagnosis, commonly associated with the presence of complications, that can range from a local abscess formation to osteomyelitis or mediastinitis. SCJ proximity with important neuro and vascular structures makes a prompt diagnosis and early therapeutic intervention crucial.3

Uncomplicated sternoclavicular SA is managed with parenteral antibiotics, while in the presence of complications surgical debridement is indicated. However, it’s important to acknowledge that early initiation of antimicrobial treatment improves outcomes, reduces the likelihood of surgical debridement and overall mortality.4-5,11 Enteroccocusspp offers intrinsic resistance to cephalosporins and is moderately sensible to penicillins, carboxipenicillins, and carbapenems.12 For that reason, we initiated a synergic combination of penicillin and aminoglycoside, with complete clinical and analytical resolution, avoiding the need for more invasive interventions. Our case adds further evidence in this uncommon but destructive pathology, raising awareness about the judicious and early antibiotic implementation.

Figura I

Repeat chest CT revealing structural bone irregularities (arrow) on the left sternoclavicular joint.

Figura II

CT- guided biopsy of the left sternoclavicular joint.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. J. J. Ross and H. Shamsuddin, “Review of 180 Cases,” vol. 83, no. 3, pp. 139–48, 2004.

2. V. C. Gobao et al., “Risk Factors, Screening, and Treatment Challenges in Staphylococcus aureus Native Septic Arthritis.,” Open forum Infect. Dis., vol. 8, no. 1, p. ofaa593, Jan. 2021.

3. A. Mohyuddin, “Sternoclavicular joint septic arthritis manifesting as a neck abscess: a case report.,” Ear. Nose. Throat J., vol. 82, no. 8, pp. 618–21, Aug. 2003.

4. S. Tasnim, A. Shirafkan, and I. Okereke, “Diagnosis and management of sternoclavicular joint infections: a literature review.,” J. Thorac. Dis., vol. 12, no. 8, pp. 4418–26, Aug. 2020.

5. H. Y. Kwon, B. Cha, J. H. Im, J. H. Baek, and J. Lee, “Medical management of septic arthritis of sternoclavicular joint,” 2020.

6. A. C. Ra, L. Er, and B. Jr, “Septic Sternoclavicular Joint : A Case Report,” vol. 89, no. May, pp. 884–6, 2008.

7. J. Edwin, S. Ahmed, S. Verma, G. Tytherleigh-Strong, K. Karuppaiah, and J. Sinha, “Swellings of the sternoclavicular joint: review of traumatic and non-traumatic pathologies.,” EFORT open Rev., vol. 3, no. 8, pp. 471–84, Aug. 2018.

8. B. S. Kang et al., “MRI findings for unilateral sternoclavicular arthritis: differentiation between infectious arthritis and spondyloarthritis.,” Skeletal Radiol., vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 259–66, Feb. 2019.

9. H. K. Song, T. S. Guy, L. R. Kaiser, and J. B. Shrager, “Current presentation and optimal surgical management of sternoclavicular joint infections.,” Ann. Thorac. Surg., vol. 73, no. 2, pp. 427–31, Feb. 2002.

10. K. Emura, T. Arakawa, A. Miki, and T. Terashima, “Anatomical observations of the human acromioclavicular joint.,” Clin. Anat., vol. 27, no. 7, pp. 1046–052, Oct. 2014.

11. N. G. R. Bayfield, E. Wang, and R. Larbalestier, “Medical and conservative surgical management of bacterial sternoclavicular joint septic arthritis: a case series.,” ANZ J. Surg., vol. 90, no. 9, pp. 1754–9, Sep. 2020.

12. N. J. Raymond, J. Henry, and K. A. Workowski, “Enterococcal Arthritis: Case Report and Review,” Clin. Infect. Dis., vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 516–22, Sep. 1995.