Introduction

Syphilis, a chronic multisystem disease, is caused by a spirochete,Treponema pallidum. It is most often sexually transmitted from an infected partner and has a huge impact on people’s physical and mental health.1 The clinical spectrum of syphilis may be primary, secondary, latent, tertiary or congenital based on time and nature of clinical presentation.2 Secondary syphilis is a systemic disease characterized by maculopapular rash, lymphadenopathy with liver and kidney involvement. Indeed, syphilis is one of the unrecognized etiologies of liver dysfunction and the incidence of syphilitic hepatitis is currently unknown.2,3 The pathogenic mechanism of syphilitic hepatitis is not currently known, but this disorder appears associated with secondary syphilis. It is extremely rare, but, nevertheless, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of cholestatic hepatitis. Therefore, clinicians should include syphilitic hepatitis in the differential diagnosis for those patients with sexually transmitted diseases presenting with liver enzyme abnormalities.4

Rates of syphilis are beginning to once again increase, with the World Health Organization estimating that in recent years there were 12 million new cases of syphilis each year.2 In fact, men who have sex with men (MSM) accounted for most reported primary and secondary syphilis cases in 2016 and 47% of syphilis cases.1,5 Despite the increasing incidence of syphilis and due to its wide variety of clinical manifestations, syphilis remains an under-diagnosed condition.5

We present a case of cholestatic hepatitis due to secondary syphilis infection in an immunocompetent patient that was diagnosed on syphilitic hepatitis.

Case Presentation

We present the case of a 47 year-old caucasian, homosexual male with no relevant past medical or surgical history. The patient reported high-risk behaviours for sexually transmitted diseases (a new male sexual partner in recent months and unprotected anal-receptive intercourse).He had no history of liver disease, minimal alcohol consumption, and no use of acetaminophen, herbals supplements, or over-the-counter products. He denied tobacco use, and had never used intravenous drugs nor had he ever received a transfusion. At the time of presentation to the emergency department, the patient reported fever accompanied by generalised pruritic rash, dark urine and fecal acholia with two weeks of evolution. Two weeks prior to presentation he was evaluated at an outside emergency department for fever and skin lesions involving the palms and soles, as well as abdominal pain and he was treated with antibiotics without clinical improvement.

On physical examination, the patient was conscious, alert and jaundiced. Vital signs were normal. There was scleral icterus, the mouth and oral pharynx appeared normal, and there was no palpable lymphadenopathy or flapping. Cardiovascular and pulmonary exams were normal. The abdomen was soft with normal bowel sounds, non-tender, non-distended, and without hepatosplenomegaly, masses, or dullness at the flanks. Both the rectal and genital exams were normal. Skin examination revealed macular erythematous lesions on the trunk, limbs, palms and soles, jaundice, but stigmata of liver disease was not observed.

From the complementary study performed during his hospitalization, we can highlight a mixed hyperbilirrubinaemia (total bilirrubin 52umol/L), increased activity of the serum enzymes alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gama-glutammyltransferase (γ-GT) and aminotransferases (ALT and AST) levels and still negative serology for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis A, B and C, epstein-barr, herpes simplex, and cytomegalovirus. Additional laboratory studies revealed a normal complete blood countas well as international normalized ratio (INR), prothrombin time and albumin were unaltered. The imagiological study excluded biliary tract obstruction with abdominal ultrasound showing homogeneous liver parenchyma without biliary ductal dilation, cholelithiasis, or cholecystitis.

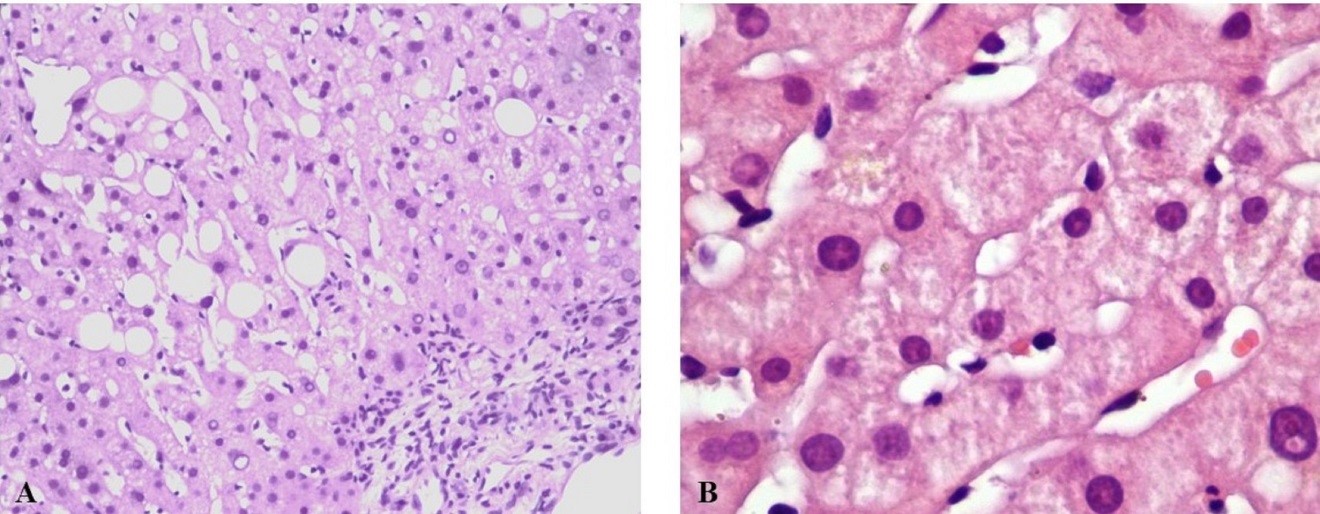

Syphilis screening (VDRL/RPR) was positive, with titers of 1:64 (Table 1)and confirmatoryand confirmatory antitreponemal antibody test specifically theTreponema pallidumconfirmed active infection. Autoimmune and metabolic workup for liver disease including anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), smooth muscle antibody (SMA), anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA), liver kidney microsomal (LKM) antibody, and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) was tested negative. Metabolic profiles including iron studies, alpha-1-antitrypsin, ceruloplasmin and celiac panel were normal. An ultrasound-guided core liver biopsy was performed and histopathology examination (Figure 1) showed acute hepatitis with mild activity (grade 2 of 4), portal and peri-portal fibrosis with no fibrous septa (stage 1 of 4).

Taken together, diagnosis of secondary syphilis with luetic hepatitis was made and the patient was treated with a single dose of benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units intramuscularly. He showed symptomatic improvement subsequently, including resolution of fever and abdominal pain. He was discharged to be followed up outpatient. Follow-up visit in two weeks revealed improvement in serum biochemical tests with ALT of 141 U/L, AST 68 of U/L, γ-GT of 720 IU/L, ALP of 324 IU/L (Table 1), and absence of fever, abdominal pain and skin lesions. Six and twelve months after therapy, VDRL was nonreactive and liver chemistries normalized entirely as presented in Table 1.

Discussion

Syphilis remains an under-diagnosed condition, mainly due to low clinical suspicion. Indeed, syphilitic infection can be a difficult diagnosis to make due to the wide variation of clinical symptoms that are associated with the disease.6

The recent increase in numbers of cases globally has been attributed to a variety of factors including increased high-risk sexual activity, travel and migration, and social and economic changes that have reduced access to medical treatment.7 In its natural course, the disease progresses from primary syphilis to secondary syphilis and tertiary syphilis if left untreated. Secondary syphilis is a systemic disorder with a wide spectrum of clinical presentations and different degrees of severity. It is typically characterized by a maculopapular rash and lymphadenopathy, but it may affect other organs, including the liver.8 Hepatitis as a complication and presentation of early syphilis is relatively uncommon. Indeed, syphilitic hepatitis, characterized by a high serum alkaline phosphatase, only occurs in up to 50% of the cases.9 The physiopathological mechanism of liver injury in secondary syphilis occurs as a result of direct damage by spirochetes as well as via autoimmune antibodies and immune complex mediated mechanisms.10

Syphilis, when presenting as acute hepatitis, is usually accompanied by elevated serum alkaline phosphatase with normal or slightly abnormal aminotransferase levels. As in this case, the pattern of liver enzymes found in syphilitic hepatitis often has a cholestatic pattern with a disproportionate elevation of alkaline phosphatase and a less prominent elevation of aminotransferases. Hyperbilirubinemia is not commonly seen.11 Liver biopsy, generally unnecessary if the diagnosis is entertained and appropriate serologic testing obtained, demonstrates nonspecific findings including focal hepatocyte necrosis, noncaseating granulomas, and portal tracts with inflammatory infiltrates; however, it is very difficult to identify the spirochetes in liver tissue among these patients.12,13In this case liver biopsy was performed in order to exclude potencioal alternative causes of liver injury.

The recommended treatment regimen for adults with secondary syphilis is benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units intramuscular in a single dose.14 As seen in our patient, following this treatment the liver enzymes rapidly improve and this response to treatment offers further confirmation of the diagnosis. All patients should be reevaluated 6 and 12 months after treatment. A four-fold reduction in titer of the nontreponemal antibody test is considered evidence of an appropriate response.4

Based on previous reports,9 syphilitic hepatitis can be defined by the following criteria: increased levels of liver enzymes that indicate hepatic involvement; serological evidence of syphilis with a positive treponemal test in conjunction with an acute clinical presentation consistent with primary or secondary syphilis; the exclusion of alternative causes of liver injury and diseases of the biliary tract and improvement in liver enzyme levels with an appropriate antimicrobial therapy. The patient in our case met all of these criteria and is a good example of the most frequent clinical features of syphilitic hepatitis. Indeed, the syphilitic aetiology of the liver injury in this clinical setting is clear. However, when confronted with a patient with liver injury, infectious, drug-induced, alcoholic, autoimmune and vascular aetiologies should be considered.15

Even today, syphilis infection remains “the great imitator” and clinicians should bear in mind the possibility of syphilitic involvement in patients at risks for sexually transmitted diseases who demonstrate liver dysfunction. Given the persistent rise in syphilis incidence along with the morbidity and mortality associated with a missed diagnosis, keen suspicion, early identification, and treatment are crucial.

Acknowledgements

The authors have an especial acknowledgment to Dr.ª Cátia Ribeiro Santos.

Quadro I

Liver Enzyme History

| Inial Presentation | Post-treatment | Post-treatment | Post-treatment | |

| (2 weeks) | (6 weeks) | (12 weeks) | ||

| Total bilirrubin (5-21 µmol/L) | 48.5 | - | 11.8 | - |

| Alkaline Phosphatese (30-120 IU/L) | 827 | 324 | 91 | 104 |

| gama-glutamyl transferase (3-45 IU/L) | 1787 | 720 | 96 | 64 |

| Alanine Aminotransferase (3-45 IU/L) | 185 | 141 | 38 | 31 |

| Aspartate Aminotransferase (15-50 IU/L) | 95 | 68 | 29 | 28 |

| VDRL/RPR (Titer) | 1/64 | 1/4 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

Liver enzyme evolution after treatment at initial presentation

Figura I

Figure 1: Liver core biopsy demonstrated (A) mild portal inflammation (low magnification hematoxylin and eosin stain). (B) A hematoxylin and eosin stained section shows the portal tracts are expanded by a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with easily identified eosinophils.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Newman L, Rowley J, Hoorn SV, Wijesspriya NS, Unemo M, Low N, et al. Global Estimates of the Prevalence and Incidence of Four Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections in 2012 Based on Systematic Review and Global Reporting. PLoS One [Internet] 2015; 10:e0143304.

Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0143304

2. Hicks CB, Clement M. Syphilis: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical manifestations in HIV-uninfected patients. UpToDate [Internet] 2019; Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/syphilis-epidemiology-pathophysiology-and clinical-manifestations-in-hiv-uninfected-patients?topicRef=7597

3. Forrest CE, Ward A. Clinical diagnosis of syphilis: a ten-year retrospective analysis in a South Australian urban sexual health clinic. Int J STD AIDS 2016;27:1334–7.

4. Suzuki I, Orfanidis N, Moleski S, Katz LC, Kastenberg D. The “Great Imitator” presents with abnormal liver enzymes. The Medicine Forum 2009;11:17.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis. 2016 Sexually transmitted diseases surveillance. Atlanta GA: CDC Division of STD Prevention; 2017 https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/Syphilis.htm. Accessed date: January 2018.

6. Lee M, Wang C, Dorer R, Ferguson L. A great masquerader: acute syphilitic hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58:923–5.

7. Stamm LV. Syphilis: Re-Emergence of an old foe. Microbial Cell 2016;3:363-70.

8. Gonzalez LC, Romero TC, Fernandez FJF, Sesma P. Secondary syphilis presenting as cholestatic hepatitis. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2013; 31: 487-8.

9. Adachi E, Koibuchi T, Okame M, Sato H, Kikuchi T, Koga M, et al. Liver dysfunction in patients with early syphilis: a retrospective study. J Infect Chemother 2013;19:180-2.

10. Rubio-Tapia A, Hujoel IA, Smyrk TC, Poterucha JJ. Emerging secondary syphilis presenting as syphilitic hepatitis. Hepatology 2017; 65:2113–5.

11. Rinascente C, Candela G, Cervero M, Lobato A, Carbonell A. Acute non cholestatic hepatitis as the first manifestation of secondary syphilis. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2015;35(3):247-9.

12. YoungMF, Sanowski RA,Manne RA. Syphilitic hepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 1992;15:174-6.

13. Huang J, Lin S,Wan B, Zhu Y. A systematic literature review of syphilitic hepatitis in adults. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2018;6(3):306–09.

14. Pastuszczak M, Wojas-Pelc A. Current standards for diagnosis and treatment of syphilis: selection of some practical issues, based on the European (IUSTI) and U.S. (CDC) guidelines. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30(4):203-10.

15. Hunter M, Brine P. An atypical presentation of a re-emerging disease. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 2017;7:49–52.