Introduction:

Thymus plays a central role in the immune system development through the regulation of T-cells tolerance to self1. Thymic epithelial tumors disrupt this process and produces cytokines, hormones and other peptides leading to immunological dysfunction, either with autoimmune disorders or paraneoplastic syndromes (PNS).1,2 The European Society for Medical Oncology guidelines recommend a ‘complete history, full clinical examination and systematic immunological work-up’ which should include serum protein electrophoresis (SPE), antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and anti-acetylcholine receptor (AChR) antibodies.3 Myasthenia gravis (MG) is the most common PNS associated with thymoma.4 However, other paraneoplastic neuromuscular manifestations are possible and clinical examination is essential to direct investigation in a stepwise approach.

We report a case of thymoma first presenting with multiple immune and humoral-mediated manifestations in order to contribute to the knowledge of the clinical spectrum of this disease.

Clinical case:

An 84-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a two-week history of dysphagia to both solids and liquids, fatigue, generalized muscle weakness and girdle-shoulder myalgia with several falls during this period. On the day of admission, she also reported an episode of coffee ground emesis. There was a known history of arterial hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and a recent episode of esophageal candidiasis. Medications included olmesartan/hydrochlorothiazide, linagliptin, acarbosis, simvastatin and acetylsalicylic acid. She was a non-smoker, who denied other toxic or over the counter medication use. On physical examination she was tachypneic, blood pressure of 70/40 mmHg and heart rate of 100 beats/min with signs of dehydration. Neurological examination revealed a symmetric proximal tetraparesis (Medical Research Council grade 3 to 4/5 of proximal muscles) with myotatic reflexes diminished on upper limbs and abolished on lower limbs. There was no sensory disturbance. Further examination exposed negative Hoffman sign, normal plantar reflexes, no ophthalmoparesis or ptosis, and normal fatigability tests.

Laboratory studies revealed a C-reactive protein elevation (81.9g/L) and acute kidney injury (serum creatinine of 262.61µmol/L and blood urea nitrogen of 14.2mmol/L). Urinary sediment was notable for microscopic hematuria and renal ultrasound was normal. A 3 to 4-fold elevation of serum aminotransferases and creatine kinase(CK) of 499U/L were present. Mild hypercalcemia was also noticed (serum ionized calcium 1.88mmol/L). Arterial blood gas analysis revealed hypoxemia and an elevated lactate of 2.5mmol/L. Chest x-ray was unremarkable.

Assuming upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding with hemodynamic instability, fluid resuscitation, supplemental oxygen and intravenous (IV) esomeprazole were begun. Upper GI endoscopy exposed extensive esophageal candidiasis and severe esophagitis whose biopsies were suggestive ofCandidaand CMV infection.

Evaluation of elevated transaminases included normal liver function tests and abdominal ultrasound, exclusion of hepatitis B, C and HIV, and a SPE which uncovered hypogammaglobulinemia with low levels of immunoglobulin (Ig) M and IgG. CMV viral load on peripheral blood was 4223IU/mL. Besides the esophagus, the muscle and liver were possible manifestations of CMV tissue-invasive disease.

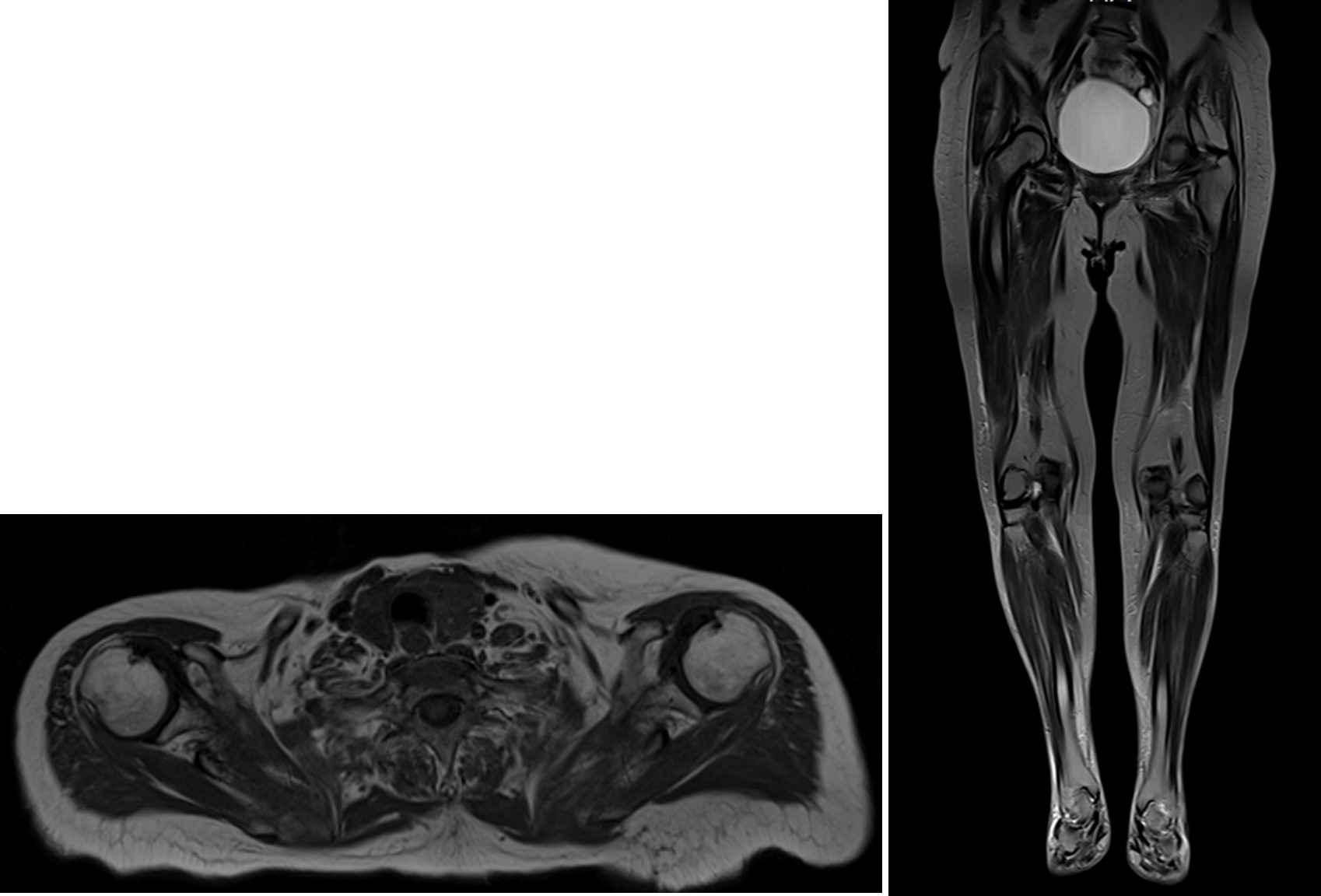

Investigation of acute non-traumatic tetraparesis included brain and cervical spine computed tomography (CT) which excluded recent vascular lesions and spondylotic myelopathy. A lumbar puncture was performed and unveiled a slight elevation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein (0.66g/L) with normal white blood cell count (<5 cells/µL). Due to albuminocytologic dissociation, a 5-day IVIg therapy was started with little improvement of muscle weakness. Electromyogram (EMG) showed myopathic irregularities with no neuromuscular junction compromise, suggesting a diffuse lesion of muscle fibers. A whole-body muscular magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed remarkable inflammatory diffuse symmetric myopathy with perifascial edema, affecting mainly the shoulder girdle and the posterior and medial compartment of the lower limbs (Fig. 1). Functional respiratory tests showed low maximal inspiratory and expiratory pressures. Further investigation revealed a positive ANA (fine speckled pattern with a titer of 1:640), anti-DFS70, anti-SSA, anti-Ro52, anti-cN1A and anti-AChR antibodies (13.1nmol/L). Notably, myositis-specific antibodies (MSA) were absent. Muscle biopsy was not possible.

Hypercalcemia investigation showed low parathormone (PTH) levels with normal 1.25-dihydroxycholecalciferol and alkaline phosphatase levels. Thyroid function was unremarkable and PTH-related peptide was negative. Partial correction of calcaemia was achieved with vigorous fluid therapy.

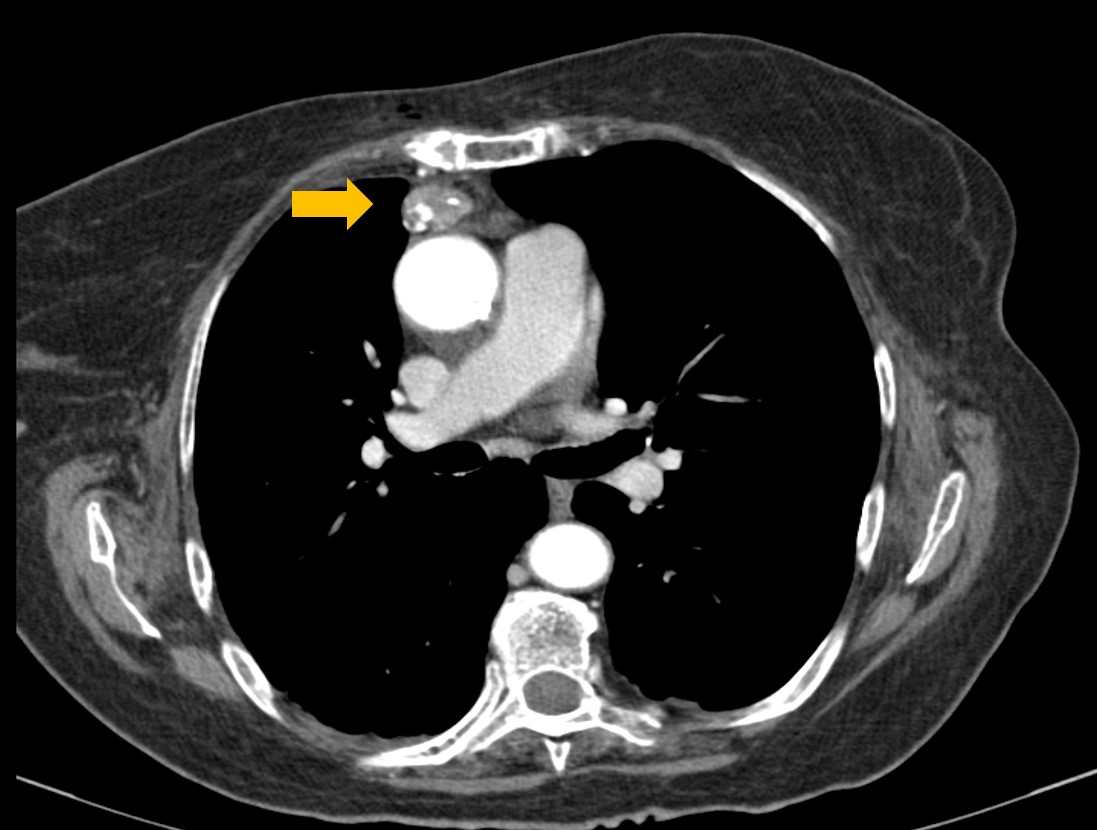

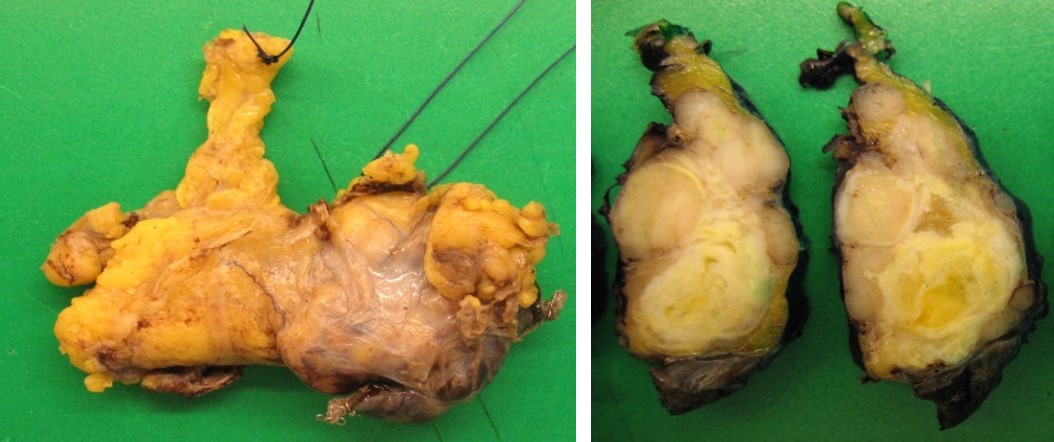

Due to suspicion of underlying malignancy, the patient underwent a chest-abdomen-pelvis CT scan uncovering a 1.2-inch anterior mediastinal mass (Fig. 2). A percutaneous core-needle biopsy was inconclusive. Then a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery was realized with thymectomy, partial lung excision and partial pleurectomy. Histopathological evaluation showed a thymoma, Masaoka stage IIB and World Health Organization type AB, with pleural invasion (Fig. 3).

During hospitalization, she completed 14-days and 21-days course of fluconazole and valganciclovir, respectively. After multidisciplinary discussion, adjunctive radiotherapy was performed. There was no recurrence of gastrointestinal bleeding and dysphagia improved after medical treatment. CMV viral load became undetectable. After surgery, muscle strength rapidly increased, CK levels normalized, and hypercalcaemia resolved.

At one-year follow-up, there was a significant recovery of muscle strength, allowing independent walking and no new symptoms appeared. CK levels were normal besides some myopathic irregularities on EMG. Hypogammaglobulinemia resolved and titers of anti-AChR antibodies decreased.

Discussion:

Acute non-traumatic tetraparesis can be a manifestation of numerous diseases. A systematic approach and thorough neurological examination are essential for differential diagnosis. Our patient presented with generalized muscle weakness along with osteotendinous hyporreflexia, absent pyramidal signs and normal head and cervical CT, thereby excluding first motor neuron lesion. Due to albuminocytologic dissociation and acute clinical presentation, Guillain-Barré syndrome was considered and IgIV was initiated. However, absence of sensory or autonomical findings, the proximal distribution of muscle weakness and rhabdomyolysis were more suggestive of muscle or neuromuscular junction disorder. Absence of fluctuation, fatigability, ocular and bulbar symptoms further narrowed the differential diagnosis to a myopathic disorder, which was confirmed on MRI and EMG. Surprisingly, our patient had a high titer of anti-AChR antibodies without clinical or EMG findings suggestive of a neuromuscular junction disorder. Concerning the etiology of the myopathic disorder, a myositis pattern was suggested by MRI. Even in possess of a muscle biopsy, distinction between viral or paraneoplastic myositis can be impossible. Both can be driven by an immunological reaction with similar histopathological findings.5 Notwithstanding, CMV myositis is rare5and our patient also fulfilled the 2017 EULAR-ACR criteria for probable idiopathic inflammatory myopathy where extensive perifascial edema is often a feature of polymyositis/dermatomyositis.6

Immunological manifestations are present in up to one third of thymoma patients1, more frequently in middle-aged Caucasian females, with early Masaoka stage disease or B-type thymomas.7,8 MG is the most frequently associated autoimmune disorder, present in about 50% of patients.1,3,9 Thymoma-associated MG is usually mediated by anti-AChR antibodies, which asymptomatic expression in this context is rare.4,7 Other autoimmune manifestations are described in 3-20% of cases, mainly pure red cell aplasia, lichen planus, Good’s syndrome, and limbic encephalitis. Half of the patients present with more than one PNS.4

Thymoma-associated myositis has been described in up to 2.8% of patients, as polymyositis or non-specified myositis4. Co-existence of MG and inflammatory myositis is rare are mainly reported as paraneoplastic phenomena in the presence of a thymoma. Case series show that these patients express anti-AChR antibodies and present with MG symptoms either before or simultaneously with those of myositis. Myositis manifestations before myasthenic symptoms is exceedingly rare. Expression of MSA or myositis-associated antibodies (MAA) is not usually seen, and muscle biopsies are most commonly suggestive of polymyositis.10–12

Further evidence of immunological dysfunction in this patient included the expression of several autoantibodies without clinical features of connective tissue disorders. Anti-Ro52 and anti-cN1A, known to be MAA, were present without other features of anti-synthetase syndrome or inclusion body myositis, respectively.13

Our patient also presented with recurrent esophageal candidiasis and CMV reactivation with hepatitis and esophagitis suggesting an underlying immunodeficiency condition. Good’s syndrome is a secondary immunodeficiency characterized by hypogammaglobulinemia, B cell lymphopenia and abnormal CD4:CD8 T cell ratio. Common infections in this context include bacterial respiratory tract infections, mucocutaneous candidiasis and CMV tissue-invasive disease that may be the first manifestation of the underlying disease.14

Hypercalcaemia is a well-known PNS even though reported association with thymomas is scarce. Mechanisms of malignancy-associated hypercalcaemia include osteolysis induced by cytokines produced by local bone lesions or humoral hypercalcaemia mediated by PTH, PTHrp or 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D secretion by tumor cells.15 Despite being unusual, we assumed that systemic production of cytokines inducing bone osteolysis was the prevailing mechanism on our patient since no other cause was found and calcium levels returned to normal after thymoma resection.

Although differential diagnosis of mediastinal masses is broad, thymomas are the most frequent cause of anterior mediastinal masses.3 Both thymoma and lymphoma can present with a calcified mass and PNS, namely, hypercalcaemia and hypogammaglobulinemia which can precede the tumor diagnosis.1

With thymoma resection, resolution of PNS is observed in 75% of the patients4. Our patient regained muscle strength and the ability to walk, hypercalcaemia resolved, titers of anti-AChR antibodies lowered and no further infectious episodes occurred, supporting the causal relationship with the thymoma.

Conclusion:

We report a case of immune dysfunction associated with thymoma, clinically presenting with myositis and asymptomatic expression anti-AChR antibodies. MAA, ANA and anti-SSA autoantibodies, Good’s syndrome and humoral hypercalcemia were additional findings. To our knowledge, this is the first description of a combination of asymptomatic expression of anti-AChR antibodies, myositis and MAA in a thymoma patient. Due to clinical heterogeneity, a comprehensive clinical evaluation is required to properly diagnose and treat these patients.

Previous presentations:This clinical case was previously presented as a short communication on the 26th Portuguese National Congress of Internal Medicine.

Figura I

T1-weighted images of muscle magnetic resonance showing inflammatory diffuse myopathy with predominantly proximal and symmetrical involvement of both upper and lower limbs.

Figura II

Chest CT scan showing a 1.2-inch partially calcified anterior mediastinal mass.

Figura III

Macroscopic appearance of resected thymoma.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

1. Padda SK, Yao X, Antonicelli A, Riess JW, Shang Y, Shrager JB, et al. Paraneoplastic Syndromes and Thymic Malignancies: An Examination of the International Thymic Malignancy Interest Group Retrospective Database. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2018;13(3): 436–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2017.11.118.

2. Jamilloux Y, Frih H, Bernard C, Broussolle C, Petiot P, Girard N, et al. Thymomes et maladies auto-immunes. La Revue de Médecine Interne. 2018;39(1): 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revmed.2017.03.003.

3. Girard N, Ruffini E, Marx A, Faivre-Finn C, Peters S. Thymic epithelial tumours: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology. 2015;26: v40–v55. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv277.

4. Zhao J, Bhatnagar V, Ding L, Atay SM, David EA, McFadden PM, et al. A systematic review of paraneoplastic syndromes associated with thymoma: Treatment modalities, recurrence, and outcomes in resected cases. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2020;160(1): 306-14.e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.11.052.

5. Gayathri Narayanappa, Bevinahalli Nandeesh. Infective myositis. Brain Pathol. 2021;31(3): e12950. https://doi.org/doi: 10.1111/bpa.12950.

6. Lundberg IE, de Visser M, Werth VP. Classification of myositis. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2018;14(5): 269–78. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2018.41.

7. Bernard C, Frih H, Pasquet F, Kerever S, Jamilloux Y, Tronc F, et al. Thymoma associated with autoimmune diseases: 85 cases and literature review. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2016;15(1): 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2015.09.005.

8. Filosso PL, Venuta F, Oliaro A, Ruffini E, Rendina EA, Margaritora S, et al. Thymoma and inter-relationships between clinical variables: a multicentre study in 537 patients. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2014;45(6): 1020–027. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezt567.

9. Gilhus NE, Tzartos S, Evoli A, Palace J, Burns TM, Verschuuren JJGM. Myasthenia gravis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2019;5(1): 30. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0079-y.

10. Uchio N, Taira K, Ikenaga C, Kadoya M, Unuma A, Yoshida K, et al. Inflammatory myopathy with myasthenia gravis: Thymoma association and polymyositis pathology. Neurology - Neuroimmunology Neuroinflammation. 2019;6(2): e535. https://doi.org/10.1212/NXI.0000000000000535.

11. Huang K, Shojania K, Chapman K, Amiri N, Dehghan N, Mezei M. Concurrent inflammatory myopathy and myasthenia gravis with or without thymic pathology: A case series and literature review. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2019;48(4): 745–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.05.004.

12. Garibaldi M, Fionda L, Vanoli F, Leonardi L, Loreti S, Bucci E, et al. Muscle involvement in myasthenia gravis: Expanding the clinical spectrum of Myasthenia-Myositis association from a large cohort of patients. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2020;19(4): 102498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102498.

13. McHugh NJ, Tansley SL. Autoantibodies in myositis. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2018;14(5): 290–302. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2018.56.

14. Multani A, Gomez CA, Montoya JG. Prevention of infectious diseases in patients with Good syndrome: Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2018;31(4): 267–77. https://doi.org/10.1097/QCO.0000000000000473.

15. Cheng C, Kuzhively J, Baim S. Hypercalcemia of Malignancy in Thymic Carcinoma: Evolving Mechanisms of Hypercalcemia and Targeted Therapies. Case Reports in Endocrinology. 2017;2017: 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/2608392.