INTRODUCTION

Autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (AAG) is a rare disorder in which there is failure of all the branches of the autonomic nervous system. It was first described in 19691and the first series was published in 1994.2 Symptoms evolve in a subacute to gradual fashion, and are caused, at least half of the patients, by antibodies targeting the ganglionic nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (AchGR).3 These have a direct pathological role and rising titers correlate with disease activity, in a mechanism akin to that of myasthenia gravis.4 The severity is variable, and the clinical course may be monophasic in a third of patients, or chronic, with lasting neurological dysfunction. In patients not responding to symptomatic treatment, there is generally a good response to plasma exchange and intravenous immune globulin (IVIG).4,5

A topic of controversy is whether the subset of patients seronegative to the anti-AchGR antibodies represent a different entity with similar phenotype or if there are pathological antibodies not yet identified. A recent study of seronegative patients6 highlighted some important differences in autonomic dysfunction patterns and response to therapy that seem to support a different pathophysiological mechanism; these observations have been challenged by other authors finding no such differences.3,7

We present a patient with seronegative AAG with a complete clinical response to IVIG treatment.

CASE REPORT

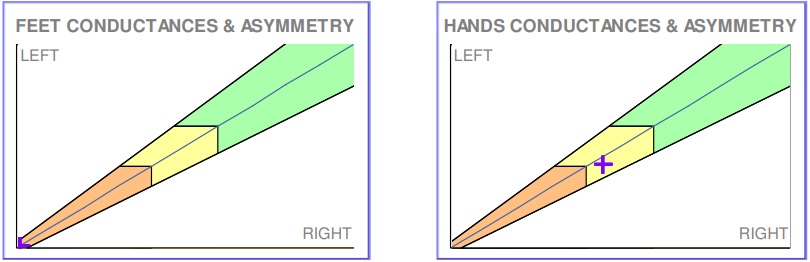

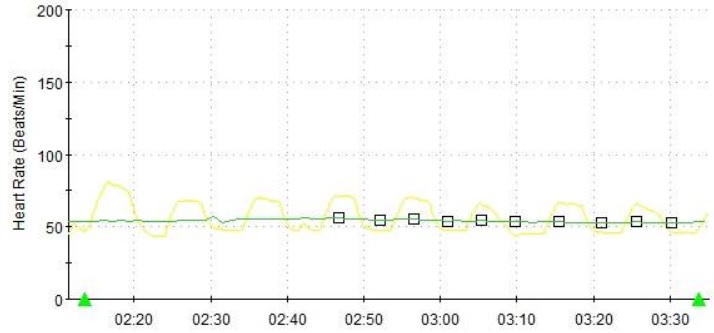

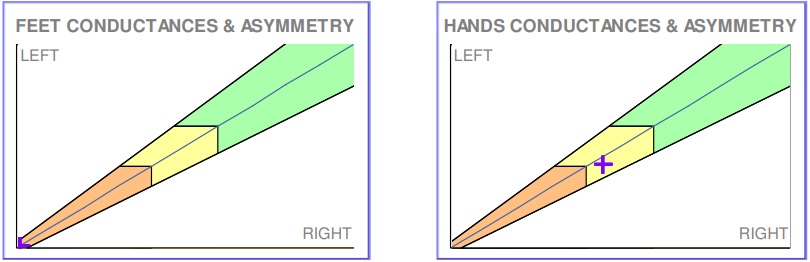

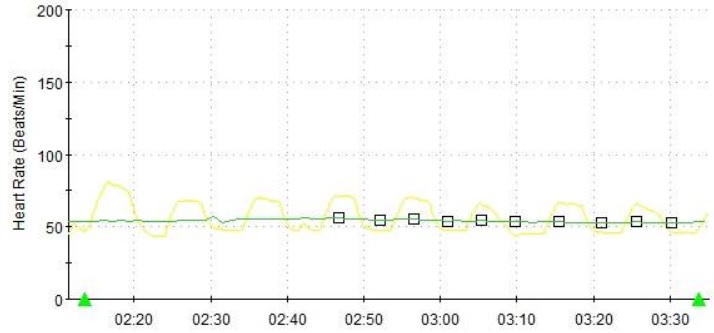

A 71-year-old hypertensive man presented to the emergency department complaining of nausea, anorexia and vomiting lasting for one month. He reported fever, myalgia, a dry cough and hiccups in the first few days, with spontaneous resolution. On further questioning he also reported dizziness on standing, dry mouth, constipation and a weak urinary stream. On physical examination there was severe symptomatic orthostatic hypotension and a dry oral mucosa with no sublingual pooling of saliva. Aside a slow pupillary response to light, the neurological examination was normal, with no signs of polyneuropathy or atypical parkinsonism. Laboratory studies yielded a normocytic/normochromic anemia with normal levels of iron, vitamins and thyroid hormones and elevation of the C-reactive protein (35mg/L). Further studies established sympathetic and parasympathetic failure: salivary scintigraphy with diffuse hypofunction, gastric scintigraphy with delayed emptying, abdominal computerized tomography (CT) showing diffuse small intestinal distention, Quantitative Sudomotor Axon Reflex Test (QSART) and electrochemical skin conductance measure by Sudoscan revealing reduced sudomotor function (Fig. 1) and abnormal heart-rate response to deep breathing (HRDB) confirming cardiovagal impairment (Fig. 2). Despite several episodes of urinary retention implying urogenital dysfunction, a urodynamic study was not performed due to a nosocomial urinary tract infection. The electromyogram showed no signs of polyneuropathy. A study of conditions associated with dysautonomia, namely a search for paraneoplastic syndromes (toracoabdominopelvic CT, positron emission tomography scan, upper endoscopy and colonoscopy, immunoelectrophoresis of serum and urine, anti-neuron antibodies), rheumatologic diseases (antinuclear antibodies, anti-SS-A and SS-B, rheumatoid factor) and amyloidosis (transthyretin gene sequencing and a search for amyloid in a salivary gland biopsy), was negative.

Testing for anti-AchGR antibodies in serum using a radioimmunoprecipitation assay in a reference laboratory was negative. A diagnosis of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy was established and the patient was treated with IVIG 2g/kg over 5 days every six weeks. Symptomatic treatment was started, with midodrine, fludrocortisone and compression stockings for orthostatic hypotension, pilocarpine drops and artificial saliva for xerostomia, prokinetics, nutritional supplements and a diet reduced in fiber for gastrointestinal hypomotility.

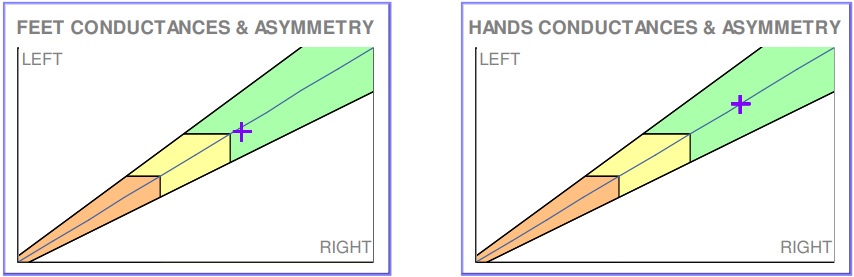

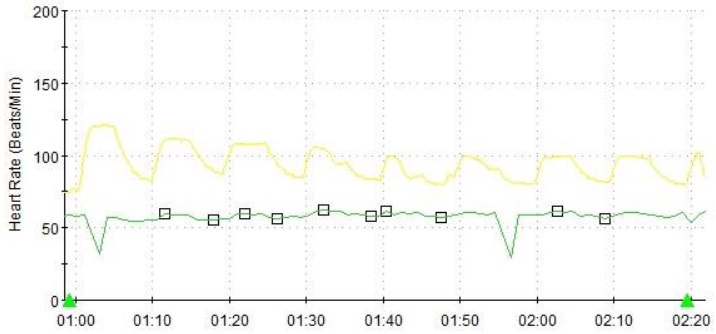

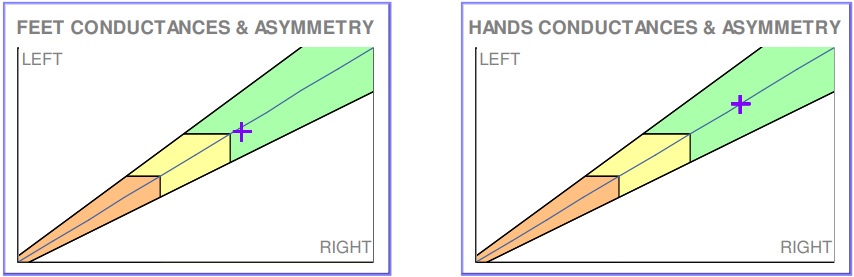

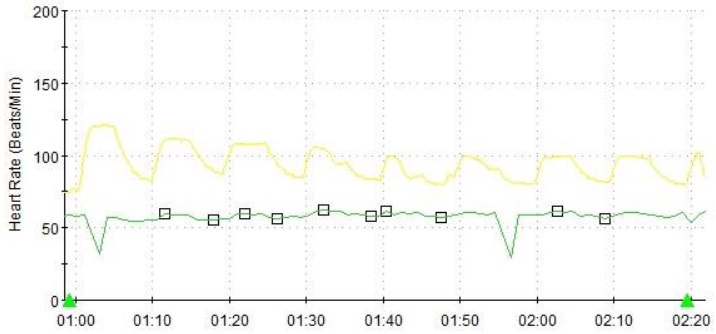

Improvement began after the first infusion, starting with the gastrointestinal symptoms, orthostatic dizziness (despite maintaining orthostatic hypotension) and urinary symptoms. After three months there was no orthostatic hypotension and sicca symptoms started improving. By six months, the patient was asymptomatic, with a normal gastric emptying scintigraphy, improved salivary function on scintigraphy and improved sudomotor function (normal sudoscan – Fig. 3, QSART with reduced sudation restricted to the foot), though HRDB remained abnormal indicating persistent parasympathetic dysfunction; abnormal HRDB persisted after one year of therapy (Fig. 4), and a tilt-test performed at this time was positive in the pharmacological phase of tilting, suggesting sympathetic dysfunction. Tapering of IgIV dose was then started, with a dosage of 1.5g/kg for 9 months, then 1g/kg the next six months, then 0.5g/kg for six months more and finally stopped altogether. After more than a year with no treatment there was no symptom recurrence. Clinical surveillance during this period did not uncover any underlying neoplasm or rheumatological disorder.

DISCUSSION

AAG is a rare disorder, with complex diagnosis involving a holistic approach, aided by the discovery of anti-AchGR antibodies, detected by two different assays with similar sensitivity and specificity.3 Pathogenicity was demonstrated by various observations, such as vertical transmission,8 reproduction of the disease by animal immunization against the AchGR9 and transfer of human antibodies,10 and a correlation between titers and severity of symptoms was also established.11

Despite accounting for approximately half the patients, seronegative AAG is less well studied and large series are lacking. A 2017 series of 6 seronegative patients seems to point a different clinical phenotype,6 with more prominent sympathetic dysfunction, no premature pupillary redilation, sensory abnormalities, no benefit from conventional therapies used in AAG (plasma exchange, IgIV, rituximab) instead responding to high-dose steroids. These findings lead to the proposal of classifying these patients as having a seronegative autoimmune autonomic and sensory neuropathy, suggesting a different pathophysiological mechanism by cell-mediated or inflammatory nerve damage. Other studies show no such clear-cut differences. A retrospective analysis of 50 patients found significant differences only in the onset of symptoms and association with underlying rheumatic disorders3; another study of 6 mixed seropositive and seronegative patients reported benefit of IVIG in their treatment12; a third retrospective study of 106 seropositive and seronegative patients did find statistically significant differences in pupillary, salivary and lower gastrointestinal function, but sensory symptoms were not evaluated and this work may have some methodological problems, namely selection bias.13 In summary, more studies are required to establish the pathogenesis of seronegative AAG and if indeed it represents a distinct clinical entity or a subset of patients whose disease is mediated by yet undiscovered antibodies. With our case we hope to contribute to this research by showing a typical subacute clinical presentation of pandysautonomia with negative anti-AchGR antibodies that responded to conventional therapy with IVIG, reinforcing the possibility of an antibody-mediated disease.

Figura I

Figure 1 – Sudoscan performed at the time of diagnosis, showing reduced sudomotor function in hands and feet.

Figura II

Figure 2 – Heart rate variability during deep breathing at the time of diagnosis, showing reduced cardiovagal tone.

Figura III

Figure 3 – Sudoscan performed six months into treatment, showing normalized sudomotor function in hands and feet.

Figura IV

Figure 4 – Heart rate variability during deep breathing one year into treatment, showing persistently reduced cardiovagal tone.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

REFERENCES

1. Young RR, Asbury AK, Adams RD, Corbett JL. Pure pan-dysautonomia with recovery. Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 1969;94:355–7.

2. Suarez GA, Fealey RD, Camilleri M, Low PA. Idiopathic autonomic neuropathy: clinical, neurophysiologic, and follow-up studies on 27 patients. Neurology. 1994 Sep;44(9):1675–82.

3. Nakane S, Higuchi O, Koga M, Kanda T, Murata K, Suzuki T, et al. Clinical Features of Autoimmune Autonomic Ganglionopathy and the Detection of Subunit-Specific Autoantibodies to the Ganglionic Acetylcholine Receptor in Japanese Patients. Saruhan-Direskeneli G, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2015 Mar 19;10(3):e0118312. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118312

4. Golden EP, Vernino S. Autoimmune autonomic neuropathies and ganglionopathies : epidemiology , pathophysiology , and therapeutic advances. Clin Auton Res [Internet]. 2019;29(3):277–88. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10286-019-00611-1

5. Koike H, Watanabe H, Sobue G. The spectrum of immune-mediated autonomic neuropathies: insights from the clinicopathological features. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry [Internet]. 2013 Jan;84(1):98–106. Available from: https://jnnp.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/jnnp-2012-302833

6. Golden EP, Bryarly MA, Vernino S. Seronegative autoimmune autonomic neuropathy : a distinct clinical entity. Clin Auton Res [Internet]. 2017;(0123456789). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10286-017-0493-8

7. Tijero B, Pino R, Pérez-concha T, Acera A, Gabilondo I, Berganzo K, et al. Seronegative and seropositive autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (AAG): Same clinical picture, same response to immunotherapy. J Neuroimmunol [Internet]. 2018;319:68–70. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2018.03.018

8. Baker SK, Chow BM, Vernino SA. Transient neonatal autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. Neurol - Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammation [Internet]. 2014 Oct;1(3):e35. Available from: http://nn.neurology.org/lookup/doi/10.1212/NXI.0000000000000035

9. Lennon VA, Ermilov LG, Szurszewski JH, Vernino S. Immunization with neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor induces neurological autoimmune disease. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(6):907–13.

10. Vernino S, Ermilov LG, Sha L, Szurszewski JH, Low PA, Lennon VA. Passive transfer of autoimmune autonomic neuropathy to mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24(32):7037–42.

11. Gibbons CH, Freeman R. Autonomic Neuroscience : Basic and Clinical Antibody titers predict clinical features of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. Auton Neurosci Basic Clin [Internet]. 2009;146(1–2):8–12. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2008.11.013

12. Iodice V, Kimpinski K, Vernino S, Sandroni P, Fealey RD, Low PA. Efficacy of immunotherapy in seropositive and seronegative putative autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. Neurology [Internet]. 2009 Jun 9;72(23):2002–8. Available from: http://www.neurology.org/cgi/doi/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a92b52

13. Sandroni P, Vernino S, Klein CM, Lennon VA, Benrud-Larson L, Sletten D, et al. Idiopathic Autonomic Neuropathy. Arch Neurol [Internet]. 2004 Jan 1;61(1):44. Available from: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/archneur.61.1.44